Antarctic Helicopter Accidents

The Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) has just issued a report into an accident involving an Airbus Helicopters AS350B2 VH-HRQ of Helicopter Resources, supporting polar exploration in Antarctica on 1 December 2013. We look at that and also Antarctic accidents involving 1 French and 3 German helicopters.

Australian Accident – History of the Flight

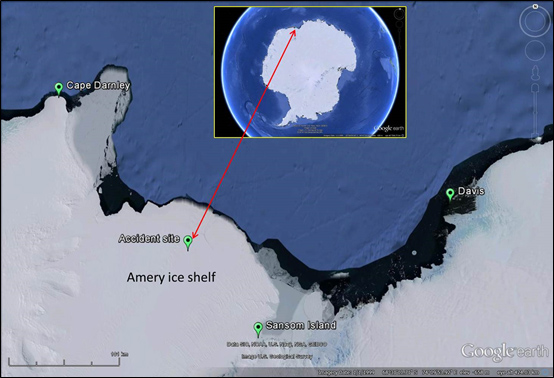

The helicopter was one of a pair returning from Cape Darnley to Davis Station, the most southerly station operated by the Australian Antarctic Division, having refuelled at a fuel cache en route on the Amery ice shelf. It had one pilot and two passengers aboard.

According to the ATSB:

As a result of a rapid reduction in visual cues, the pilot of [ZH-]HRQ maintained about 150 ft above ground level. The pilots of both helicopters discussed the reduced surface definition and loss of visible horizon along their flight path and elected to return to the fuel cache until the weather improved. During the turn back to the fuel cache, HRQ descended and impacted the ice shelf. The pilot and two passengers were seriously injured and the helicopter destroyed.

The second helicopter landed near-by but bad weather prevented recovering the casualties for 20 hours. Temperatures was around -8 degrees Celsius.

VH-HRQ Wreckage – Note how the MGB has slid forward into the cabin (Credit: Helicopter Resources via ATSB)

Australian Accident – Analysis

The ATSB believe that, after initiating the right turn back to the fuel cache, the pilot probably became spatially disoriented and thus didn’t detect the decent, commenting:

Factors contributing to the disorientation included a loss of visual cues as a result of the change in weather conditions, and a breakdown of the pilot’s scan of his flight instruments, resulting in collision with terrain.

When interviewed by the press, the ATSB’s Chief Commissioner Martin Dolan said the pilot was faced with a challenging situation:

The basic cause was a loss of situational awareness by the pilot in conditions where there was no visible horizon, so essentially a white-out, and [he turned] to try and get back to a safe position but in the course of that the helicopter collided with terrain.

In those situations there’s a very high workload on pilots, you’ve got a combination of checking externally to see what’s happened, to respond to a situation where the visibly has suddenly dropped, and there’s a range of things you also need to check internally in terms of the management of the aircraft.

The aircraft was approved in Australia for Day and Night VFR operations but was not equipped with an autopilot, nor was one required by local regulation. The ATSB had previously reported on an accident involving an AS355, chartered by a TV company, during Night VFR operation were the lack of an autopilot was contributory.

The pilot was experienced (4800 hours+) but had completed just eight hours of instrument flying in an AS350. Doran commented:

That’s a comparatively low number of hours and so the lack of instrument flight would have been a potential contributor here.

ATSB note in their report:

The operator had recognised the hazards associated with flight in Antarctic conditions and had implemented turn-backs/night training to addresses the associated risk. This training was conducted using flight instruments to maintain height in the turn.

On the accident flight, a timely decision by the pilot to reference both the flight instruments and the clear horizon to the right, rather than flying by visual reference only, would most likely have provided the additional safety margin necessary to maintain terrain clearance during the return to the landing site.

The report contains further background on spatial disorientation and the operator’s risk assessments of Antarctic operation.

ATSB also discuss some previous accidents in similar conditions:

- Hughes 369 VH-PMY in Antarctica in 1982

- AS350s N6007S, N6052C and N6099Y in an infamous series of related accidents on Juneau Galcier, Alaska in 1999

- AS350 ZK-HGI on a glacier in New Zealand in 2005

- AS350 C-FBHN in British Columbia in 2012

Australian Accident – Safety Action

The ATSB report that:

Following this accident the operator introduced new helicopters equipped with an autopilot and other equipment to reduce pilot workload. They also introduced simulator training that is administered by an experienced Antarctic pilot, a situation awareness course, and training on the use of the autopilot in the new helicopters and limitations of the radar altimeter. The operator has also amended their operational documentation to prescribe minimum settings for radar altimeters, discuss the use of the autopilot in low visibility environments, and provide decision-making guidance in relation to early avoidance of, and action on encountering inadvertent white-out conditions.

Although not in response to this accident, on 17 March 2015 an amendment to Civil Aviation Order 20.18 was registered. This amendment will require a helicopter operating under the visual flight rules at night to have an autopilot or stability augmentation system, or to include a two-pilot crew where orientation cannot be maintained ‘by the use of visual external surface cues as a result of lights on the ground or celestial illumination’.

The change to the required aircraft equipment, effective 1 January 2016, recognises that control of a helicopter that is operating under the visual flight rules at night is significantly more difficult when there are limited external visual cues.

Other Recent Antarctic Accidents

Four people died on 28 October 2010 when AS350 F-GJFJ, being operated by SAF Helicopters for the French polar research institute, the Institut Paul Emile Victor (IPEV), collided with terrain in poor and decreasing visibility. In their report the BEA state:

On 28 October 2010, the pilots of two helicopters operated by SAF HELICOPTERES were flying passengers and equipment from the Astrolabe ship to the Dumont d’Urville base in Adélie Land (Terre Adélie). These flights were undertaken following damage to the ship’s propeller, which caused the ship to halt its progress towards Dumont d’Urville. When the decision was made to undertake the flights, the meteorological conditions at the ship and at the base 207 NM away were good. The flying autonomy and performance of the helicopters were compatible with the flights planned.

The pilot of the two helicopters took off about 20 minutes apart. The pilot of the first helicopter encountered poor weather conditions when in cruise, which led him to decide to continue the flight at low altitude, sometimes below 200 ft, to remain under the cloud layer. The pilot of the second helicopter, registered F-GJFJ, initially decided to fly above this cloud layer, but then decided to turn around and also fly below the cloud layer. The pilot made two 360° turns at low speed and at a low height once below the cloud layer.

The helicopter collided with the surface of the pack ice. The last flight path data points recorded indicated a height of about 30 ft.

The investigation showed that the accident was caused by the pilot likely losing all external visual references, following his decision to undertake and continue the flight in unfavourable meteorological conditions, in a hostile environment that offered no or few alternatives to the plan of action.

The specific context of the mission, the absence of operational documentation relating to operations in Adélie Land and SAF HELICOPTERES failure to submit part C of its operations manual to the oversight authority were factors contributing to the accident. The pilot having taken medication with sedative effect may have contributed to the accident.

Five safety recommendations were issued to DGAC and EASA (several relating to oversight of remote operations):

- An amendment to the regulations to provide a clearer definition of the concept of an operations base and the procedure for declaring a new base,

- The description of the areas of operation defined in the operator’s AOC and for which the latter has declared an operations base,

- The obligation to inform the oversight authority of any operations in remote locations,

- The introduction of a more effective oversight system for operators by the oversight authority,

- Organising an awareness-raising campaign on the risks relating to self-medication for flight crew.

On 17 December 2011, two Bo105s of HeliService International, D-HANT and D-HLSZ were operating from the German polar research ship Polarstern. In their report (only available in German), the BFU describe how the aircraft made a precautionary landing before pressing on and encountering whiteout conditions.

The same operator, flying from the same ship had a fatal accident in the Antarctic in 2008.

UPDATE 17 December 2015: See also our article: Canadian Coast Guard Helicopter Arctic Accident: CFIT, Survivability and More

UPDATE 24 November 2019: Austrian Police EC135P2+ Impacted Glassy Lake

UPDATE 14 November 2020: HEMS EC135T1 CFIT During Mountain Take Off in Poor Visibility

UPDATE 11 December 2021: Canadian Flat Light CFIT

UPDATE 5 August 2022: Heliski Flat Light Flight into Terrain

UPDATE 19 November 2022: Whiteout During Avalanche Explosive Placement

Recent Comments