Low Viz Helicopter CFIT Accident, Alaska (TEMSCO Airbus AS350B2 N94TH, 6 May 2016)

On 6 May 2016, Airbus Helicopters AS350B2 N94TH, operated by TEMSCO Helicopters, collided with snow-covered mountainous terrain about 4 miles southeast of Skagway, Alaska in a Controlled Flight Into Terrain (CFIT).

The helicopter had departed from a remote landing site, surrounded by mountains, on the Denver Glacier on a visual flight rules (VFR) flight with internal cargo. Instrument meteorological conditions (IMC) were however reported on the Denver Glacier at the time. The non-instrument-rated pilot was fatally injured.

The Accident Flight

The US National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) safety investigation report (released in October 2018) explains that:

Alaska Icefield Expeditions contracted with TEMSCO to provide helicopter support for the movement of personnel, dogs, and cargo. The purpose of the flight was to transport dog camp company personnel (mushers) and dogs (Alaskan Huskies) from…Skagway to a remote dog camp on the Denver Glacier in the Tongass National Forest, about 5 miles southeast of Skagway.

The pilot was ready to begin flight operations at 0800, but low ceilings prevented flight operations. The pilot attended company orientation training at 0900, and, at 1300, he provided helicopter loading training for new TEMSCO employees. At 1530, the pilot completed the training and evaluated the weather for flight operations. The pilot determined that the wind conditions were unsuitable at the time but were forecast to improve later in the afternoon.

At around 16:45 the pilot commenced the first of 7 planned round trips.

At 1840, the helicopter departed for the sixth trip with 1 musher and 12 dogs onboard.

As the helicopter passed through Paradise Valley, the passenger reported that the valley itself was “wide open” with a rainbow present, but he and the pilot could see that the clouds were “moving in” as the helicopter approached the Denver Glacier.

The passenger reported that the clouds were “thick,” and he could not see up the glacier toward the dog camp. The passenger further reported that the western mountain wall near the glacier was visible at the time, so the pilot elected to follow the wall into the dog camp “very slowly.” He stated that the helicopter was “very low” with regard to the bluff and was closer to the wall than he had ever been on previous flights up to the dog camp.

The dog camp manager reported that just before the sixth flight arrived, the wind speed was up to 20 to 30 mph, and it was snowing. The clouds had moved in and covered the bluff; visibility was about a 1/4 mile looking toward Paradise Valley. The helicopter landed at the dog camp, and the musher and 12 dogs were unloaded. Before the pilot left, he signaled for the dog camp manager and told him that he was “not coming back in this weather.” The dog camp manager verbally agreed. The dog camp manager told the pilot to be safe, and the pilot said to the dog camp manager, “but don’t give up on me yet.”

The NTSB suggest this last statement would be consistent with self-induced pressure to complete the flying programme. The FAA’s Helicopter Flying Handbook, FAA-H-8083-21, states:

There are numerous classic behavioral traps that can ensnare the unwary pilot. Pilots, particularly those with considerable experience, try to complete a flight as planned, please passengers, and meet schedules. This basic drive to achieve can have an adverse effect on safety and can impose an unrealistic assessment of piloting skills under stressful conditions. These tendencies ultimately may bring about practices that are dangerous and sometimes illegal and may lead to a mishap. Pilots develop awareness and learn to avoid many of these operational pitfalls through effective single-pilot resource management training.

The NTSB note that:

The TEMSCO Operations Manual discusses company VFR weather minimums and states that, for the local operating area (within a 30-nautical-mile radius from the base of operations), a 500 ft ceiling or greater and 1 statue mile visibility or greater is required. A review of the TEMSCO Operations Manual found no operational procedures listed for flight operations in deteriorating VFR weather conditions (such as reduced visibility and ceilings), inadvertent instrument meteorological conditions (IIMC) avoidance procedures, or IIMC recovery procedures.

The pilot subsequently departed from the dog camp at 1852.

The dog camp manager’s observations and radar data indicated that the pilot attempted to depart via the normal route to the south but turned around. He likely encountered low visibility conditions and then attempted several departures by routes to the north of the dog camp. About 8 minutes after departure, the helicopter impacted snow-covered mountainous terrain about 2 miles northeast of the dog camp.

About 1900, the TEMSCO base manager noted that he had not heard any communication on the radio for a few minutes, so he asked about the status of the accident helicopter and noticed on the flight tracking computer that the helicopter’s position was northwest of the dog camp at an elevation of about 6,200 ft msl, about 2,000 ft above the dog camp’s elevation. He made several radio calls to the pilot, and no responses were received.

After repeated radio calls with no response from the pilot, the base manager decided to launch in a helicopter with an observer on onboard. The company emergency response plan was activated. At 1914, the base manager departed to the last known coordinates of the missing helicopter. The base manager reported that he was unable to fly over the dog camp via Paradise Valley at 1924 due to low ceilings, blowing snow, and turbulence.

Temsco had a telephone conference with FAA and NTSB at 2000, prior to any contact with the emergency services. At 2009 hours a Temsco aircraft radioed they had located aircraft N94TH and that appeared “destroyed” . High winds and blowing snow prevented them landing anywhere near the accident site. It was only at 2012 that an emergency call was made for Search and Rescue (SAR). A US Coast Guard (USCG) SAR helicopter was dispatched at 2100 and a rescue crewman confirmed the fatality sometime after 2215.

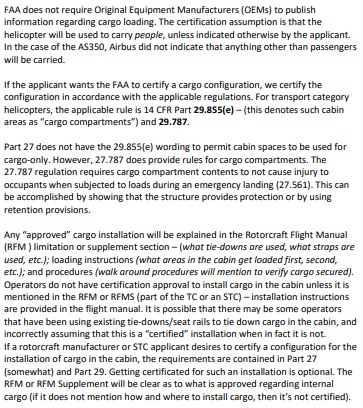

During the impact sequence, the two cargo straps used to secure two wooden dog boxes to the rear cabin floor failed, and the dog boxes shifted forward, striking the back of the pilot’s fiberglass seat.

Dog Box and Pilot’s Seat in Wreckage of Temsco Airbus AS350B2 N94TH, Denver Glacier, AK (Credit: NTSB)

The cause of death for the pilot was attributed to multiple blunt force injuries. It could not be determined if the forward movement of the dog boxes during the accident sequence contributed to the injuries sustained by the pilot.

The Artex ME406 emergency locator transmitter (ELT) antenna wire had separated during the accident sequence.

Background and NTSB Analysis

The NTSB found no pre-existing anomalies with the aircraft itself. They say:

Given the deteriorating weather conditions when the pilot departed, it is likely that the pilot continued visual flight into an area of instrument meteorological conditions, which resulted in the pilot experiencing a loss of visual reference and subsequent controlled flight into terrain.

On one of the day’s previous flights, the pilot reported to the base manager, who was exercising operational control at the time of the accident, that he had encountered icing conditions while in flight. The base manager told the pilot “to do what he thought was best.”

However, flight operations in icing conditions are prohibited by the helicopter’s rotorcraft flight manual and the operator’s operations manual, and the pilot’s statement should have prompted the base manager to suspend the flights.

The TEMSCO Operations Manual discusses operational control and states:

Operational control with respect to a flight, means the exercise of authority over initiating, conducting, or terminating a flight. The Director of Operations and the pilot in command are jointly responsible for the initiation, continuation, diversion, and termination of a flight. The Director of Operations may delegate functions to other trained personnel, but retains responsibility for initiation, continuation, diversion, and termination. The final authority over conducting or terminating a flight rests with the pilot in command. The following persons have “operational control” with respect to flight in descending order: director of operations, chief pilot, pilot in command, second in command, director of maintenance, base managers, base lead pilot, and trained flight followers.

The base manager’s failure to appropriately exercise operational control and terminate the flights may have been due to the difference in experience between the base manager, who had been operating these flights for 8 years, and the pilot, who had been operating these flights for 25 years.

Aircraft Configuration and Weight and Balance

The NTSB also examined the aircraft configuration:

TEMSCO configured the helicopter cabin to facilitate the transportation of internal cargo. The rear seat assembly was folded up against the cabin wall, and two wood, dog transportation boxes were placed behind the front seats.

The dog boxes were stacked vertically and secured using two cargo straps attached to a total of four seat belt attachment rings installed on the floor of the cabin.

Both cargo straps were secured to the rear seat belt attachment points in front of the aft cabin wall, routed over the top of the stacked boxes, and secured to the pilot and front passenger seat belt attachment points. With the configuration of the two cargo straps, forward restraint was present; however, no lateral restraint was present.

The make and model of the cargo straps, as well as the maximum load rating of the straps, could not be determined. The two cargo straps had abrasions at various locations along with unknown stains throughout the length of the straps.

The NTSB queried the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) policy on cargo in the cabin and received the following response:

…the Airbus AS 350 Systems and Descriptions Manual states, “further to removing the front [left seat] and folding back the rear benches, the cabin floor can be used to transport cargo. The eleven mooring points are embedded into the floor and are also used to attach the seatbelts.” The manual also lists the “limit permissible force on a mooring ring” as 620 dekanewtons or 1393.7 pound-force.

…Airbus stated in an email to the NTSB IIC that “it is the responsibility of the operator to define an adapted cargo, freight, or baggage securement that is in respect to the limitations permissible force on the floor stowing mooring rings.” On June 26, 2018, the Bureau d’Enquêtes et d’Analyses pour la sécurité de l’aviation civile reported to the NTSB IIC that Airbus has developed a “cargo installation in cabin” procedure for the Airbus AS 350 series, which is currently in the certification process.

NTSB investigators also identified errors in weight and balance calculations:

The combined weight of the two wood dog boxes was 190.5 pounds; the wood boards used for shoring on the cabin floor weighed 9.5 pounds; and the blanket, tarp, and two cargo straps weighed 5 pounds. The total weight of 205 pounds was not included on the cargo manifest documents for the day’s flights or the helicopter’s weight and balance record.

On each of the first four flights from Skagway to the dog camp, the total dog weight entered on the cargo manifest form was 500 pounds (10 dogs on board). On the fifth flight, the dog weight entered was 550 pounds (11 dogs on board). On the sixth flight, the dog weight entered was 600 pounds (12 dogs on board).

Consequently:

For all six flights from Skagway to the dog camp, the weight of the dog boxes and related items (205 pounds) combined with the dog weight resulted in the structural limitation of 682 pounds being exceeded.

Tour Operators Program of Safety

At the time of the accident, the operator was a member of the Tour Operators Program of Safety (TOPS). The most recent TOPS compliance audit on the operator before the accident took place from August 8 through August 10, 2015. All the audit areas (management, safety, flight operations, pilots, flight coordination, heliport, maintenance, maintenance personnel, and ground support personnel) along with base visits and flight observations were classified as “meets TOPS standards.”

NTSB Probable Cause

The pilot’s decision to continue visual flight into an area of instrument meteorological conditions, which resulted in the pilot experiencing a loss of visual reference and subsequent controlled flight into terrain.

Contributing to the accident were the pilot’s self-induced pressure to complete the flight and the operator’s failure to maintain operational control over the flight.

The Day Before… (UPDATED 21 March 2020)

On 5 May 2016 AS350B2 helicopter N194EH, operated by Era Helicopters, suffered a Controlled Flight Into Terrain (CFIT) while on approach to a remote landing site on the Norris Glacier in flat light. We examine that accident on our article: Alaskan AS350 CFIT With Unrestrained Cargo in Cabin

Other Safety Resources

UK CAA Paper 2007/03: Helicopter Flight in Degraded Visual Conditions:

Final summary report on research conducted for the CAA by QinetiQ on helicopter flight in degraded visual conditions. The work comprised a review of accident data for the period 1975 to 2004, simulator trials using two test pilots and six representative accident scenarios, analysis of the simulator trials results including linking quantitative measures of visual scene content with pilot workload ratings, and a review of relevant civil regulations.

Also see these Aerossurance articles:

- All Aboard CFIT: Alaskan Sightseeing Fatal Flight

- US Fatal Night HEMS Accident: Self-Induced Pressure & Inadequate Oversight

- Night Offshore Winching CFIT

- US Police Helicopter Night CFIT: Is Your Journey Really Necessary?

- Fatal Night-time UK AW139 Accident Highlights Business Aviation Safety Lessons

- ‘Procedural Drift’: Lynx CFIT in Afghanistan

- Italian HEMS AW139 Inadvertent IMC Accident

- HEMS A109S Night Loss of Control Inflight

- Deadly Combination of Misloading and a Somatogravic Illusion: Alaskan Otter

- How a Cultural Norm Lead to a Fatal C208B Icing Accident

- Torched Tennessee Tour Trip (B206L N16760)

- Wait to Weight & Balance – Lessons from a Loss of Control

- Misloading Caused Fatal 2013 DHC-3 Accident

- Culture + Non Compliance + Mechanical Failures = DC3 Accident

- UPDATE 5 February 2019: Japanese Rescue B412 Fatal CFIT

- UPDATE 2 November 2019: Taiwan Night Medevac Helicopter Take Off Accident

- UPDATE 31 December 2019: Costa Rican C208B Stalled While Trying To Avoid High Ground

- UPDATE 13 April 2020: Inadequately Secured Pallets Penetrate the Rear Pressure Bulkhead of a Cargo B737

- UPDATE 5 February 2021: Inexperienced IIMC over Chesapeake Bay (Guimbal Cabri G2 N572MD): Reduced Visual References Require Vigilance

- UPDATE 11 December 2021: Canadian Flat Light CFIT

- UPDATE 5 August 2022: Heliski Flat Light Flight into Terrain

Recent Comments