False Fire Warning and Unfeathered Propeller KA200 Accident

Beechcraft B200 Super King Air VH-MVL of the Royal Flying Doctor Service (RFDS) was substantially damaged during a single engined landing on 13 December 2016.

The Accident Flight

The aircraft was conducting a visual approach to Moomba Airport, South Australia (SA), following an air ambulance flight from Innamincka, SA. According to the Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) safety investigation report:

As the aircraft turned onto the base leg of the approach, the pilot observed the left engine fire warning activate.

The ATSB comment that:

The pilot was wearing an active noise reduction headset and the aircraft warning horns are broadcast through a cockpit speaker, rather than the intercom system. Consequently it was the warning light, rather than the warning horn which captured the pilot’s attention.

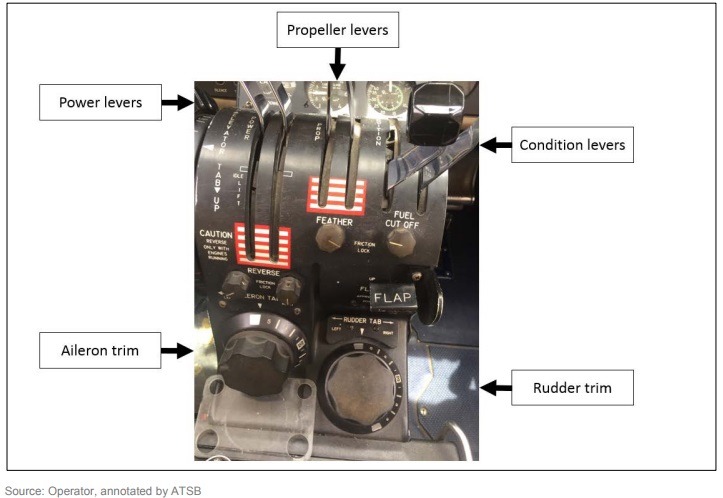

The operator’s emergency checklist procedure….‘emergency engine shutdown’….included boxed bold type immediate actions… performed from memory:

1. Condition Lever… …FUEL CUT OFF

2. Prop Lever… …FEATHER

3. Firewall Shutoff Valve… …CLOSED

4. Fire Extinguisher… …ACTUATE (If required)

The company procedure was to complete the immediate actions from memory and then reference the checklist to confirm immediate actions were completed before completing the remainder of the actions.

In this case:

The [pilot] pulled the [left engine] condition lever, then paused, then closed the firewall shutoff valve and pressed the extinguisher and confirmed it had discharged, all from memory, but there was no time to reference the checklist during the approach.

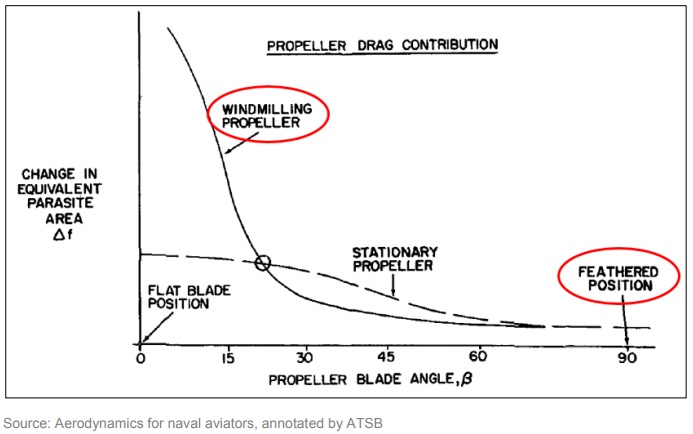

The propeller feathering (i.e. to rotate the blades to an edge-on angle to the airflow) was omitted, so the left hand propeller was windmilling, and thus producing drag. The sole pilot commenced a right turn towards the runway.

Due to the pilot’s position in the left seat, they were initially unable to sight the runway… The aircraft had flown through the extended runway centreline when the pilot sighted the runway to the right of the aircraft. The aircraft was low on the approach and the pilot realised that a sand dune between the aircraft and the runway was a potential obstacle. They increased the right engine power to climb power…raised the landing gear and retracted the flap to reduce the rate of descent. The aircraft cleared the sand dune and the pilot lowered the landing gear and continued the approach to the runway from a position to the left of the runway centreline.

The aircraft landed in the sand to the left of the runway threshold and after a short ground roll, spun to the left and came to rest. There were no injuries and the aircraft was substantially damaged.

Safety Investigation: Aerodynamics and Aircraft Performance

The ATSB comment that:

A windmilling propeller can produce a significant amount of drag, which is estimated to be comparable to a parachute canopy of the same area as the propeller disc area.

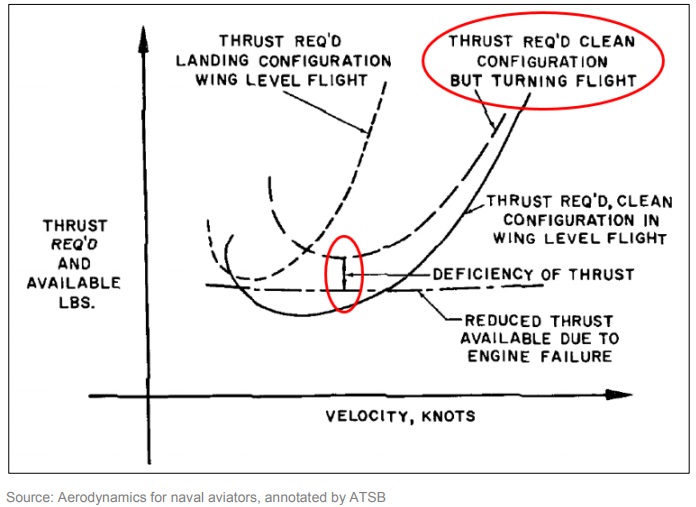

In addition, the aircraft was in a right turn, towards the engine developing power, with the landing gear extended and the flaps set to approach. This combination resulted in more thrust being required for continued safe flight than was available.

These factors adversely affected the aircraft performance.

Safety Investigation: Pilot Actions and Pilot Training

The pilot reported that they hesitated in their decision-making and subsequent engine fire drill actions because of their uncertainty in the veracity of the indication and their proximity to landing.

At the time of the master warning, they had just started the base turn on approach to land, which required their attention to be divided between the cockpit settings and indications, and the external cues for the visual approach. It is possible that divided attention, combined with their hesitation…contributed to them omitting the step to feather the propeller in their immediate actions.

The pilot…

…did not attempt to feather the propeller at any stage during the approach. This indicates that the pilot did not recognise that their asymmetric handling difficulties were the result of a windmilling propeller….

The pilot’s training and assessment reports indicated that their asymmetric flight experience on the B200 extensively involved engine failures on take-off and engine fires in cruise.

The simulator field of view for the pilot is less than what is available in the aircraft. [Hence] the operator assessed it as inappropriate to initiate emergencies in the simulator from a circuit base leg position. Therefore critical situation emergencies, such as an engine fire indication on approach, were generally initiated on the final approach of an instrument approach.

An autofeather system will feather the propeller of a failed engine during take-off. In cruise, the propeller must be manually feathered by the pilot..

The pilot’s previous successful handlings of an engine fire in the simulator [meant] it is likely the pilot had no prior experience of the B200 handling characteristics with a windmilling propeller, which likely contributed to them not recognising (and recovering) from that condition within the timeframe of the accident sequence. The ATSB only offers this as a possible explanation for why the pilot did not associate the performance and handling difficulties with a windmilling propeller. Operating the aircraft with a windmilling propeller was not a competency requirement.

The ATSB also note that:

The accident pilot did not receive the operator’s published syllabus of training for the B200 King Air. Instead, a tailored training program was delivered in consideration of the pilot’s experience on the C90 King Air with another operator and advice the operator received from the Civil Aviation Safety Authority. This training did not cover all the elements required under the Civil Aviation Safety Regulations.

Safety Investigation: Fire Warning and Continuing Airworthiness Management / SMS

No engine fire damage was found and it was therefore concluded that the observed fire warning was almost certainly a false warning.

The pilot commented that they were aware that the fire detection system was susceptible to false indications due to sunlight entering the engine compartment, but had not previously experienced such an incident.

The RFDS acquired VH-MVL in 1997 and it had no prior history of false fire warnings. They did have had four previous reports of false in-flight engine fire warnings recorded in the rest of their KA200 fleet:

- A left engine fire warning, which extinguished after about 30 seconds (13 March 2003).

- A left engine fire warning, which extinguished after about 30 seconds. A fire detection probe was replaced (22 March 2003).

- A left engine fire warning. The pilot conducted the immediate actions. The response recorded in the report was to check the fire detection probes for serviceability (24 April 2003).

- A left engine fire warning which activated momentarily on approach. After landing, the warning activated and remained illuminated. The pilot conducted the immediate actions. There was no evidence of fire found and a fire detector was replaced. The warning light activated three times on the return flight. A fault in the wiring harness connector was recorded as the reason (10 July 2005).

The ATSB say:

…the optical fire detection system fitted to the aircraft was susceptible to false indications. In 1995, Beechcraft issued a service bulletin (SB 2596) for a continuous loop fire and overheat detection system to ‘improve reliability and maintainability.’

In July 2003, after the first three reports of false engine fire indications, the RFDS reviewed the SB “but elected not to incorporate the modification”. Ten years later, on 10 April 2013, the Australian aviation regulator CASA issued an airworthiness bulletin (AWB 26-005) that “strongly recommended” installation of SB 2596 (but CASA did not choose to make the SB mandatory). The operator again considered the SB but elected not to embody it. Both operator reviews made no reference to the risk posed by false engine fire indications, however…

…the operator’s previous false engine fire warning [safety] reports recorded them as low risk and their last report was in 2005.

The earliest safety management manual the operator was able to provide the investigation was dated 2006….therefore the operator’s risk assessment process, as it applied to the earlier false engine fire warnings and review of SB 2596 was not investigated any further.

The ATSB say:

…that the incorporation of the manufacturer’s modification would have reduced the risk of a false fire warning occurring.

ATSB Findings

Contributing factors

- The operator did not modify the aircraft to include a more reliable engine fire detection system in accordance with the manufacturer’s service bulletin…

- During the approach phase of flight, the pilot shutdown the left engine in response to observing a fire warning, but omitted to feather the propeller. The additional drag caused by the windmilling propeller, combined with the aircraft configuration set for landing while in a right turn, required more thrust than available for the approach.

Other factors that increased risk

- The advice from the Civil Aviation Safety Authority to the operator, that differences training was acceptable, resulted in the pilot not receiving the operator’s published B200 syllabus of training. The omission of basic handling training on a new aircraft type could result in a pilot not developing the required skilled behaviour to handle the aircraft either near to or in a loss of control situation.

Other findings

- The pilot met the standard required by the operator in their cyclic training and proficiency program and no knowledge deficiencies associated with handling engine fire warnings were identified.

Safety Actions

The comprehensive planned RFDS actions are to:

- Conduct a review of their current recruitment process, including entry standards and consideration of additional processes to the current standard of interview and simulator test.

- Engage with a university to study pilot recruitment in order to better understand the ideal pilot traits required for the company’s operations.

- Conduct a review of existing pilot induction/training/clearance to line procedures, and increase use of Level D simulator wherever possible for initial and recurrent emergency procedures.

- All new pilots will complete the company’s full induction training, including aircraft endorsement training.

- Review and rewrite of the company operations manual, and training and checking manual.

- Accelerate the introduction of the flight data analysis program and undertake a trial of line orientated safety audit.

- Install flight data recorders on all aircraft and include flight data recorders as a mandatory item for aircraft standards.

- Install Pratt & Whitney flight acquisition, storage and transmission (FAST) on all aircraft and include FAST as a mandatory item for aircraft standards.

- In-person briefing program with the pilot workforce to discuss findings and agreed safety actions from the company’s internal investigation with a focus on lessons learned from the accident.

CASA intends to take steps to refresh industry and CASA officers of particular terms and concepts within the CASR 1998 flight crew licensing suite to remove any doubt that might exist as to their interpretation and applicability. For example, terms such as differences training, flight review, competency, competency-based-training, recognition of prior learning, qualifications and experience will be clarified.

ATSB Safety Message

Following the accident, the pilot reported that their biggest lesson was not to hesitate during emergency procedures. They believed that their doubt in the veracity of the warning resulted in their hesitation while completing the four engine fire drill (memory) actions, resulting in them missing the step to feather the propeller.

This accident also highlights the need for organisations to consider all the relevant information available to them when making decisions, such as the process for reviewing non‑mandatory service bulletins. Organisational decision-making should consider the potential consequences of human error when evaluating changes.

Aerossurance sponsored the 2017 European Society of Air Safety Investigators (ESASI) 8th Regional Seminar in Ljubljana, Slovenia on 19 and 20 April 2017. ESASI is the European chapter of the International Society of Air Safety Investigators (ISASI).

Aerossurance is pleased to be supporting the annual Chartered Institute of Ergonomics & Human Factors’ (CIEHF) Human Factors in Aviation Safety Conference for the third year running. We will be presenting for the second year running too! This year the conference takes place 13 to 14 November 2017 at the Hilton London Gatwick Airport, UK with the theme: How do we improve human performance in today’s aviation business?

Recent Comments