Gulfstream G-IV Take Off Accident & Human Factors (N121JM)

The US National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) has highlighted a number of important human performance issues in a recent Board Meeting held to discuss a Gulfstream G-IV business aircraft accident. UPDATE 24 September 2015: The full final report is now published.

The Accident

On 12 May 2014, 3 crew and 4 passengers died when G-IV N121JM, registered to SK Travel LLC, and operated by Arizin Ventures LLC under Part 91 rules, was destroyed at the joint civil/military Hanscom Field (BED) in Bedford, Massachusetts, after a night-time high speed rejected takeoff and runway excursion.

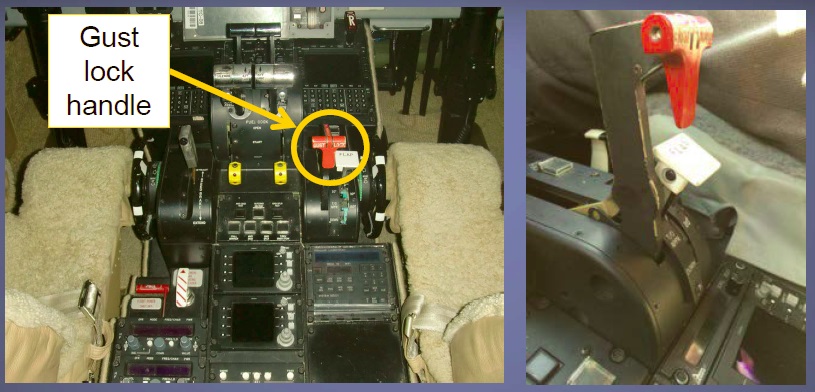

Aerossurance discussed the preliminary findings of the investigation in July 2014: Focus on Gust Locks After US GIV accident. The gust lock system is used to lock the elevator, ailerons and rudder when parked to protect against damage in gusting wind. Indeed, the failure to unlock the gust locks prior to commencing take off was a critical failure.

This NTSB video illustrates the take off:

The aircraft overran the 2,137 m (7,011 feet) runway, collided with approach lights and a localizer antenna, went through the perimeter fence and ended up in a small ravine 564 m (1,850 feet) from the end of the runway, where the post crash fire took hold.

Among the dead was Lewis Katz, co-owner of the US’s third-oldest daily newspaper. the Philadelphia Inquirer. Katz died just days after agreeing a $88 million deal, with partner Jerry Lenfesto, be sole owners of the newspaper’s parent company.

The flight crew were experienced. The aircraft commander had >11,000 total flight hours (with > 1,600 hours on the G-IV) and the first officer >18,000 total flight hours (with >3,000 hours on the G-IV). They had flown together for about 12 years, a fact which is worth noting when we discuss human performance matters below.

The NTSB abstract on that accident is here. The NTSB determined that the probable cause of this accident was:

… the flight crewmembers’ failure to perform the flight control check before takeoff, their attempt to take off with the gust lock system engaged, and their delayed execution of a rejected takeoff after they became aware that the controls were locked. Contributing to the accident were the flight crew’s habitual noncompliance with checklists, Gulfstream Aerospace Corporation’s failure to ensure that the G-IV gust lock/throttle lever interlock system would prevent an attempted takeoff with the gust lock engaged, and the Federal Aviation Administration’s failure to detect this inadequacy during the G-IV’s certification.

From the NTSB abstract and presentations we observe five human performance aspects to this accident:

Human Performance Aspect 1 – Omitting to Disengage Gust Locks

During the engine start process, the flight crew didn’t disengage the aircraft’s gust lock sustem. This omission should not on its own be fatal as there where at other safeguards (one procedural, a status indication and a physical design feature) that should act as further risk controls.

Human Performance Aspect 2 – Omitting a Flying Control Check

The flight crew failed to perform a flight control check. This procedural control would have alerted them that the controls remained locked. It is noteworthy that when the NTSB reviewed flight data from the aircraft’s Quick Access Recorder (QAR), they discovered that this flight crew had failed to perform complete flight control checks before 98% of their previous 175 take offs. To the NTSB this indicated that this omission was “habitual”. The NTSB comment that:

SK Travel [sic – note not Arizin Ventures] flight operations manual required flight crews to complete all appropriate checklists. Company policy did not specify preferred method of checklist completion.

[The crew] did not call for checklists, did not verbalize checklist items [and that] executing checklists silently and from memory removes many benefits [of checklists].

Consistency of accident flight crew’s noncompliance suggests development of shared attitudes.

The NTSB describe this a procedural drift (a topic we have discussed in our recent article: ‘Procedural Drift’: Lynx CFIT in Afghanistan). The NTSB say:

Small operators with consistent crew pairings and less oversight may have increased risk.

They go on to state that in this case:

Independent safety audits performed by an industry safety organization did not adequately encourage best practices for the execution of normal checklists.

Human Performance Aspect 3 – Rudder Limit Light

The Cockpit Voice Recorder (CVR) data indicates that the crew did discuss a blue, advisory, Rudder Limit Light as they taxyed onto the runway. While the weakest of the three extra safeguards, it was an opportunity for concern to be raised and prompt a check before commencing take off.

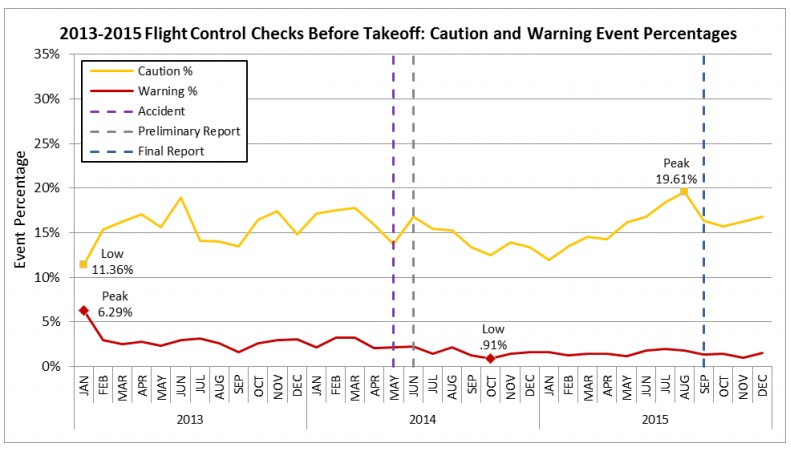

Human Performance Aspect 4 – A Flawed Mechanical Interlock

As the crew advanced the throttles the third safeguard should have come into play. This design feature, intended to protect against errors and procedural violations, is a mechanical interlock between the gust lock handle and the throttle levers. It was intended to limit the throttle lever angle (TLA) to no greater than 6° with the gust lock on. This would have prevented the aircraft “achieving any significant acceleration” and was required to meet certification requirement Part 25.679.

However, the NTSB discovered that:

…postaccident testing on nine in-service G-IV airplanes found that, with the gust lock handle in the ON position, the forward throttle lever movement that could be achieved on the G-IV was 3 to 4 times greater than the intended TLA of 6°.

Gulfstream has released two maintenance and operations letters to G-IV operators since the accident (see our earlier article) and is currently developing a modification to the interlock.

Human Performance Aspect 5 – Aborting the Take Off

Having had the Rudder Limit Light, a further abnormality emerged, in that the desired Engine Pressure Ratio (EPR) did not quite reach the desired level manually (seemingly acknowledged by a CVR comment), though selection of Autothrottle meant the aircraft ultimately able to accelerate to 162 knots in this accident. The aircraft commander was the Pilot Flying and the NTSB state that when attempting to rotate the aircraft:

… he discovered that he could not move the control yoke and began calling out “(steer) lock is on.” At this point, the PIC clearly understood that the controls were locked but still did not immediately initiate a rejected takeoff. If the flight crew had initiated a rejected takeoff at the time of the PIC’s first “lock is on” comment or at any time up until about 11 seconds after this comment, the airplane could have been stopped on the paved surface. However, the flight crew delayed applying brakes for about 10 seconds and further delayed reducing power by 4 seconds; therefore, the rejected takeoff was not initiated until the accident was unavoidable.

With the benefit of hindsight (and thousands of hours of accident investigator efforts on this take off attempted collated for our education) its easy to think that ‘they could have aborted the take off earlier’ and indeed if this was a simulator exercise we would have expected it. In practice though, it should be remembered that it was less than 30 seconds from advancing the throttles to applying the brakes. The NTSB comment that:

…this delay likely resulted from surprise, the unsuccessful attempt to resolve the problem through use of the flight power shutoff valve, and ineffective communication.

NTSB Safety Issues and Recommendations

The NTSB go on to identify five issues (four directly connected to the human performance aspects above), each with a safety recommendation:

1) Use of the challenge-verification-response format for checklist execution:

The flight crewmembers’ total lack of discussion of checklists during the accident flight and the routine omission of complete flight control checks before 98% of their last 175 flights indicate that the flight crew did not routinely use the normal checklists or the optimal challenge-verification-response format. This lack of adherence to industry best practices involving the execution of normal checklists and other deficiencies in crew resource management eliminated the opportunity for the flight crewmembers to recognize that the gust lock handle was in the ON position and delayed their detection of this error.

This resulted in a recommendation to the International Business Aviation Council (IBAC) to:

Amend International Standard for Business Aircraft Operations [IS-BAO] auditing standards to include verifying that operators are complying with best practices for checklist execution, including the use of the challenge-verification-response format whenever possible.

There is a view, as for example expressed by Sidney Dekker, that in practice procedures must be interpreted by front-line personnel and that non-compliances should be viewed in context of the circumstances the crew find themselves. This does not seem relevant in this case however in relation to a failure to use checklists.

The NTSB has also adopted a safety alert (SA048 Flight Control Locks: Overlooking the Obvious) about using checklists to ensure procedural compliance. This aspect of checking compliance leads on to the next NTSB safety issue…

2) Analysis of corporate Flight Operations Quality Assurance (FOQA) data (i.e Flight Data Monitoring [FDM]) to define the scope of procedural noncompliance in business aviation.

NTSB found no data documenting the rate of flight crew compliance with required flight control checks in business aviation for the G-IV or any other airplane, yet checklists, callouts, and other standard operating procedures (SOP) are considered an important “soft” defense against threats and errors in business aviation. If the actual rate of procedural compliance is much lower than assumed, aircraft designers, regulators, and operators may need to help boost compliance or reconsider their assumptions about the reliability of flight crew adherence to routine checks and the level of safety protection afforded by such SOPs.

This resulted in a recommendation to the National Business Aviation Association (NBAA):

Work with existing business aviation flight operational quality assurance groups, such as the Corporate Flight Operational Quality Assurance Centerline Steering Committee [a Flight Safety Foundation initiated initiative], to analyze existing data for non-compliance with manufacturer-required routine flight control checks before takeoff and provide the results of this analysis to your members as part of your data-driven safety agenda for business aviation.

While the NTSB are interested in a study to better understand compliance in business aviation, it is certainly noticeable in this case that FDM data was available that could have identified habitual practices inconsistent with procedures. How the organisation conducted FDM is not discussed in the abreact NTSB report or the PowerPoint presentations. FDM is certainly an opportunity to also address the first NTSB issue, albeit one difficult to exploit in an ‘operator’ of one aircraft and one crew.

3) Retrofit of the gust lock system on all existing G-IV airplanes to comply with the certification requirement that the gust lock limit the operation of the airplane so that the pilot receives an unmistakable warning if the lock is engaged at the start of takeoff.

Performance calculations demonstrated that the interlock mechanism did not perform as intended. If the throttles had remained at the point where they initially contacted the interlock, the airplane would have reached rotation speed about 7 seconds later and about 1,200 ft farther down the runway than it did. In contrast, an interlock that limited TLA to 6° would have prevented the airplane from achieving any significant acceleration, thus constituting an unmistakable warning that would most likely have prevented the accident.

This resulted in the following recommendation to the FAA:

After Gulfstream Aerospace Corporation develops a modification of the G-IV gust lock/throttle lever interlock, require that the gust lock system on all existing G-IV airplanes be retrofitted to comply with the certification requirement that the gust lock physically limit the operation of the airplane so that the pilot receives an unmistakable warning at the start of takeoff.

4) Guidance on the appropriate use and limitations of the review of engineering drawings in a design review performed as a means of showing compliance with certification regulations.

The G-IV gust lock/throttle interlock system was based on previously certificated Gulfstream airplane systems, and compliance with the applicable certification regulation (14 CFR 25.679, Control System Gust Locks) for the G-IV was demonstrated by a review of engineering drawings. There was no functional test of the design of the G-IV gust lock/throttle interlock system. A drawing review was an insufficient means of demonstrating compliance with 14 CFR 25.679 because of the complexities of the G-IV gust lock system. Design review as a means of compliance with a regulation and the specific documentation requirements are not defined in FAA guidance material such as FAA orders or advisory circulars.

It is surprising that compliance verification detailed in a certification plan would consist only of inspection of drawings, rather than (at minimum) a simple ground test. This resulted in the following recommendation to the FAA:

Develop and issue guidance on the appropriate use and limitations of the review of engineering drawings in a design review performed as a means of showing compliance with certification regulations.

5) Unrelated to the human performance matters but of relevance to survivability matters: Replacement of nonfrangible fittings with frangible fittings for any objects along the extended runway centerline up to the perimeter fence.

After leaving the paved runway overrun and entering the grass, the airplane collided with structures that were not mounted on frangible supports. These structures were not required to be mounted on frangible supports; only structures inside the runway safety area (RSA) must have frangible supports. The NTSB recognizes that the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) already encourages the incorporation of frangible fittings for structures in areas adjacent to RSAs and that it replaced the fittings at BED with frangible fittings after the accident. However, similar nonfrangible structures located outside of an RSA, but inside a perimeter fence and along an extended runway centerline, are likely present at other airports.

This resulted in the following recommendation to the FAA:

Identify nonfrangible structures outside of a runway safety area during annual 14 Code of Federal Regulations Part 139 inspections and place increased emphasis on replacing nonfrangible fittings of any objects along the extended runway centerline up to the perimeter fence with frangible fittings, wherever feasible, during the next routine maintenance cycle.

UPDATE 22 September 2016: NTSB Board Member Robert L. Sumwalt presented Lessons from the Ashes: The Critical Role of Safety Leadership to an audience in Houston, TX. Its worth noting the emphasis made of safety as a ‘value’ and of alignment across an organisation. This accident is one considered.

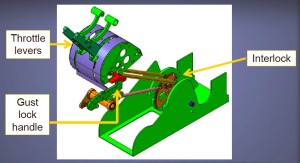

UPDATE 23 September 2016: The NBAA has published their report: Business Aviation Compliance With Manufacturer-Required Flight-Control Checks Before Takeoff

The [FDM] data [analysed] shows that out of 143,756 flights conducted during the 2013 to 2015 time period, flight crews [only] conducted a partial flight-control check before takeoff (caution event) during 22,458 flights (15.62 percent). There was no flight-control check before takeoff (warning event) conducted on 2,923 flights (2.03 percent). For the three-year period covering 2013, 2014 and 2015, the overall noncompliance rate for manufacturer-required routine flight-control checks before takeoff was 17.66 percent, reflecting 25,381 events.

After the accident on May 31, 2014, and the release of the preliminary report on June 13, 2014, the average warning event rate was reduced to 1.47 percent, a drop of 50 percent. That may indicate there was a positive reaction to the preliminary report finding that the Bedford crew did not perform any flight-control check before takeoff. The caution events are more variable, and there is not a significant difference in caution event rates between pre- and post-accident percentages.

This report to the NBAA membership is not only intended to provide closure action to the NTSB recommendation, but also to raise awareness to the broader business aviation community that complacency and lack of procedural discipline have no place in our profession.

NBAA President and CEO Ed Bolen said:

As perplexing as it is that a highly experienced crew could attempt a takeoff with the gust lock engaged, the data also reveals similar challenges across a variety of aircraft and operators. This report should further raise awareness within the business aviation community that complacency and lack of procedural discipline have no place in our profession.

In 1992 the gust locks had not been fully disengaged on a third-party DHC-4T Turbine Caribou conversion, N400NC, leading to a horrific fatal accident that killed 3.

UPDATE 27 September 2016: Bizav ‘Has Long Way To Go on Safety,’ Says NBAA Chief at the 20th annual Bombardier Safety Standdown in Wichita. Commenting after the their re-flight flight control check report of the Ed Bolden said:

We have to understand the data and then find some way to move from reactive to proactive. If there’s a challenge, then we need to find a mitigation strategy. It’s an important and noble pursuit.

UPDATE 24 October 2016: Execuflight Hawker 700 N237WR Akron Accident: Casual Compliance A disturbing accident after an unstabilised approach that begs serious questions of the operator’s procedures and culture.

UPDATE 7 May 2017: We also look at another case of poor pre-flight checks: Ground Collision Under Pressure: Challenger vs ATV: 1-0

UPDATE 10 May 2017: For more background on the G-IV investigation see: What Happens After a Crash?

UPDATE 2 August 2017: FAA AD on gust lock modification on Gulfstream G-IV jets becomes effective

UPDATE 19 May 2018: If you had spent 2 years rebuilding a classic Piper PA-12 you’d make the time to check the rigging of the flying controls before first flight, right? Sadly, the pilot in this fatal case study was in a rush: Too Rushed to Check: Misrigged Flying Controls

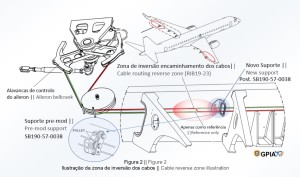

UPDATE 31 May 2019: The Portuguese accident investigation agency, GPIAAF, issued a safety investigation update on a serious in-flight loss of control incident involving Air Astana Embraer ERJ-190 P4-KCJ that occurred on 11 November 2018. The aircraft was landed safely after considerable difficulty, so much so the crew had debated ditching offshore. GPIAAF conformed that incorrect ailerons control cable system installation had occurred in both wings during a maintenance check conducted in Portugal.

GPIAFF note that: “By introducing the modification iaw Service Bulletin 190-57-0038 during the maintenance activities, there was no longer the cable routing and separation around rib 21, making it harder to understand the maintenance instructions, with recognized opportunities for improvement in the maintenance actions interpretation”. They also comment that: “The message “FLT CTRL NO DISPATCH” was generated during the maintenance activities, which in turn originated additional troubleshooting activities by the maintenance service provider, supported by the aircraft manufacturer. These activities, which lasted for 11 days, did not identify the ailerons’ cables reversal, nor was this correlated to the “FLT CTRL NO DISPATCH” message.”

GPIAFF comment “deviations to the internal procedures” occurred within the maintenance organisation that “led to the error not being detected in the various safety barriers designed” in the process. They also note that the error ” was not identified in the aircraft operational checks (flight controls check) by the operator’s crew.”

UPDATE 1 June 2019: Our analysis: ERJ-190 Flying Control Rigging Error

UPDATE 8 June 2020: Fatal Falcon 50 Accident: Unairworthy with Unqualified Crew

UPDATE 4 October 2020: Investigators Suggest Cultural Indifference to Checklist Use a Factor in TAROM ATR42 Runway Excursion

UPDATE 4 April 2021: Fatal 2019 DC-3 Turbo Prop Accident, Positioning for FAA Flight Test: Power Loss Plus Failure to Feather

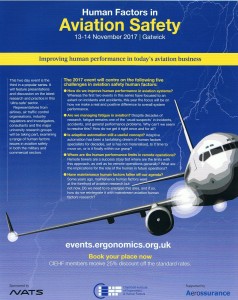

Aerossurance is pleased to be supporting the annual Chartered Institute of Ergonomics & Human Factors’ (CIEHF) Human Factors in Aviation Safety Conference for the third year running. This year the conference takes place 13 to 14 November 2017 at the Hilton London Gatwick Airport, UK with the theme: How do we improve human performance in today’s aviation business?

We also recommend our previous article: James Reason’s 12 Principles of Error Management

Recent Comments