Human Factors of Dash 8 Panel Loss

We look at the human factors lessons after Flybe Bombardier DHC-8-402 / Dash 8 Q400 G-PRPC was damaged by the loss of an engine access panel on departure from Manchester Airport on 14 December 2016.

The UK Air Accidents Investigation Branch (AAIB) discuss the circumstances of the panel loss in their report. The aircraft…

…night-stopped at Manchester Airport…parked on a remote stand. The operator’s contracted maintenance organisation [at Manchester] completed a routine daily check on the aircraft that evening. This included checking the oil content of the No 1 engine, accessed by opening the outboard main access panel on the engine nacelle.

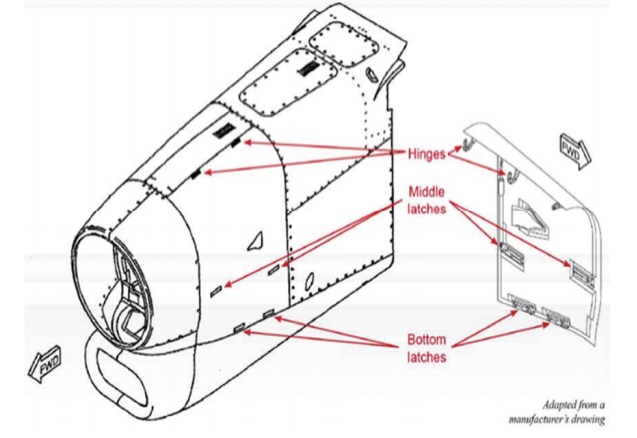

The main engine bay of each engine nacelle has two large forward access doors, one inboard and one outboard. These access doors are made from a carbon/epoxy composite material with integral foam-filled stiffening ribs. Each door is hinged at the top, has a single telescopic hold-open strut and is secured in the closed position by four quick-release lock pin latches.

Each latch, when closed, engages a pin into a receiver mounted within the engine nacelle structure. The outboard door on the No 1 engine and the inboard door on the No 2 engine allow access to service the engine oil system. The check was concluded by approximately 2115 hrs… The aircraft Technical Log entry for the daily check was signed by the engineer at 0010 hrs.

At 0550 hr…the commander conducted the pre-departure inspection. As it was still dark, he used a torch to supplement the ambient airport lighting during his inspection. The inspection had a total duration of 3 minutes. He did not identify any issues with the aircraft and the crew continued with their normal departure routine.

The ground crew, who were responsible for pushing the aircraft back off the stand, subsequently arrived and conducted their own walkround check of the aircraft, also identifying nothing of note.

The aircraft departed for Hanover and on arrival there about 90 minutes later it was noticed that the No 1 engine access panel was missing. A search was initiated at Manchester and…

…the panel was recovered from a grass area to the side of the runway, approximately 440 m from the runway threshold. Sections of the panel hold-open strut were also recovered from the runway and adjacent paved areas in the same vicinity.

On inspection of the recovered panel all four latches were found to be in the closed and latched position. There was no damage to the latch bolts or the receiving fixtures on the nacelle.

As there was no damage to the latches the AAIB concluded the panel latches had been closed correctly.

Inspection of the aircraft vertical stabiliser showed puncture holes in the skin on both sides, with impact marks also present on the leading edge de-icing boot.

Damage to vertical stabiliser Flybe DHC-8-402 Dash 8 (Q400), G-PRPC. Similar damage occurred on both sides. (Credit: AAIB)

There was also impact damage to both VOR/LOC antennas.

Other Incidents and Earlier Action

According to Bombardier there have been nine other engine access panel losses in-flight worldwide on the Q400 fleet in similar circumstances. One in South Africa on ZS-NMO in July 2014 was subject to a more basic investigation by the South African CAA, who finally reported on 8 January 2018. However in that case the lower two latches were found unlatched and only the two upper/middle latches were in the latched position.

One occurrence had been on the same Flybe aircraft, G-RPPC. The AAIB say that 9 November 2016 the No 1 engine access panel was found missing from G-PRPC after a flight from Belfast to Glasgow. In that case the departing panel caused damage to the left wing leading edge de-icing boot and wing skin.

Three weeks later the operator issued Notice to Engineers (NTE) 22 that stated:

Following completion of all work either an independent person carries out a walkround inspection to verify all access panels are fitted/secure, or the certifying engineer must return after a notable period of time for a double check of the security of the disturbed panel security. The independent person could be a technician or a pilot, or the notable period of time could be after completion of paper work.

The NTE did not require this inspection to be specifically recorded.

Maintenance Human Factors

Staff of the contracted maintenance provider at Manchester Airport stated that they were unaware of the existence of NTE 22 at the time the December 2016 incident…

…so had not conducted any additional post-maintenance inspection to check the security of the latches and panels. The operator’s safety investigation established that, unlike the operator-owned maintenance subsidiary, there was no procedure in place for contracted maintenance company staff to read and sign NTEs.

The AAIB go on:

The routine daily check requirement was laid out in a set of task sheets where each task, once completed, required sign off by an engineer licensed on type. Checking the engine oil content of each engine was listed as tasks 26 and 27.

These tasks were highlighted as safety critical and had a requirement for an independent check of the oil cap (or repeat inspection after a period of time, in the case of a licenced engineer completing the task). There was no similar instruction regarding the closing of the panel.

Whilst the task stated the oil contents check should be in accordance with the Aircraft Maintenance Manual (AMM), a subsequent review with the aircraft manufacturer confirmed that, at the time of this event, the AMM did not contain any instructions on opening or closing the engine access panel.

No comment is made on whether this lack of AMM instructions was realised after after the first incident.

The operator’s expectation was that each item on the…task sheet would be signed for. The individual pages would then be certified complete and an entry would be added to the aircraft Technical Log, stating that the daily check had been completed. [Copies] should then have been posted to the operator’s HQ in accordance with their procedures.

The operator’s safety investigation identified that the contracted maintenance company was not certifying the individual tasks or task sheet pages, but was just adding an entry directly into the aircraft Technical Log. The hard copy documents were also not being sent to the operator.

Its not explained why this was not apparently identified by quality control checks or audits. The AAIB then explain:

Interviews with the engineers involved in both the first and second incidents identified a common technique used to secure the engine access panel. This involved closing the two upper [i.e. middle] latches first, followed by the two lower ones.

Practical assessment of this technique showed that occasionally, as a result of a slight misalignment of the panel, it did not close correctly… Given the height of the panel and shorter distance to the hinge line, it was difficult to apply the necessary force to fully engage the panel at the level of the top latches, when compared to applying a similar force at the bottom of the panel. This could result in the top latches being closed, without the panel being properly located. As a consequence, the locking pin would not be engaged in the receiving fixture on the nacelle side, but the latch would externally look and feel as if it was properly closed. Once the upper latches were closed in this manner, the panel would rest on the upper latch pins. Significant force could then be applied to the bottom of the panel while the lower latches were closed, but the pins would not engage in their receiving fixtures. The only external visual confirmation of the incorrect closure of the panel, was a small gap between the access panel and the surrounding nacelle panels.

Panel gap resulting from an incorrectly latched panel viewed from the ground under

similar lighting conditions to both incidents (Credit: AAIB)The engineers in both incidents involving G-PRPC were standing on steps to access the engine which meant once the access panel was closed, they were looking downwards at the panel and using a head torch to supplement the ambient lighting on the stand.

View of the panel gap following incorrect closure, from the perspective of the engineer

conducting the task (Credit: AAIB)[The image above] shows how the perspective of the gap in the panel changes, when viewed under these circumstances. This would have been further exacerbated on the incident aircraft as the surrounding panels were painted purple rather than white, providing much less contrast to the shadow cast by the access panel.

Flight Crew Human Factors

The AAIB say operator’s Operations Manual provided clear guidance on how a pre-departure inspection should be completed. However, there was a degree of inconsistency in the way in which this is demonstrated to flight crew during their type training.

Following the first access panel loss in November 2016, the operator’s Flight Operations department issued Notice To Air Crew (NOTAC) 146/16 – ‘Engine Cowling and Hatches Inspection’, to request extra vigilance whilst conducting pre-departure inspections. The aircraft commander from the second incident on G-PRPC confirmed that he had read this document prior to the flight, but commented in interview that as he had previously been a flight engineer it did not contain any information that was new to him.

This highlights one of the limitations of safety promotion material that simply highlights known information.

The commander stated that he was aware that a daily maintenance check had been signed for in the aircraft Technical Log and that this involved opening the engine access panels. When asked how he would normally assess that the access panel was secure, he stated that the latches would be flush. He advised that this was taught to him during his recent Q400 type conversion course, and was shown to him during the hangar visit and during his line training [five months earlier].

Ground Ops Human Factors

Ground handling staff are not required to have any technical qualifications and routinely work on various aircraft type. They were not sent the operator’s NOTAC or NTE and had only generic training on confirming that “doors, panels and latches are closed and secure”.

Operator Safety Actions

Flybe…

…subsequently revised NTE 22 post-incident to introduce a procedure where a sticker is placed over the bottom of the panel, when it is closed post-maintenance. This provides visual and tactile confirmation to the engineer that the panel is correctly closed and secured. Two further NOTACs (63/16 and 64/16) have subsequently been issued by the operator, to provide specific guidance in identifying correct panel and door closure during the predeparture inspection and to highlight the engineering requirement to use a sticker over the engine access panel to confirm correct closure.

Manufacturer’s Safety Actions

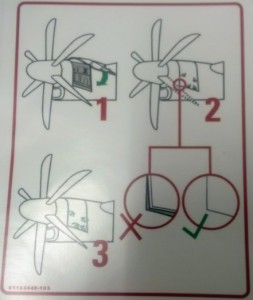

Bombardier issued AMM Temporary Revision 71-197, which now gives instructions on how to close the engine nacelle access door. It is also developing a modification to add a placard which provides pictorial guidance.

AAIB Analysis and Safety Recommendations

The engineers conducting the maintenance daily check prior to both incidents were experienced and well trained staff, who had safely completed the same task many times during the years preceding these incidents. They came from different companies, with separate training organisations and operated at different airports.

No significant contributing factors were identified which differentiated these two incidents from any previous occasions that they had completed the same task successfully. The only apparent common links were the technique used to close the panel, the physical positioning of the engineer as this was done and the lighting conditions at the time.

The fact that the engineers were then looking down on the panel, which was predominantly illuminated by the beam from a head torch, meant that the main indication of the gap at the bottom of the panel was only visually identifiable by the shadow that was cast. As the surrounding panels were painted purple this may not have been obvious, particularly considering that the engineer was not expecting the panel to be open once the latches were closed, was not specifically checking for the presence of a shadow, and may not have appreciated the implication of the presence of a shadow in this position.

If flight crew are not shown the difference between correctly and incorrectly closed panels, misunderstandings such as the belief that closed latches confirm the panel is secure can become accepted custom and practice, and incidents such as this may continue to occur.

The AAIB raised the following Safety Recommendation:

Safety Recommendation 2017-014: It is recommended that Flybe introduces defined and consistently delivered flight crew training on pre-departure inspections for the DHC-8-402 (Q400), compliant with the inspection procedure documented in its Operations Manual. This should include a practical element on the aircraft and a demonstration of correctly secured main engine access panels.

Inspection by the ramp staff:

…should only be considered a gross check and cannot be relied upon to address issues such as closed but incorrectly secured panels. However, there is potentially some benefit to the operator in increasing general awareness using specifically targeted guidance information relating to safety issues.

The AAIB raised the following Safety Recommendation:

Safety Recommendation 2017-015: It is recommended that Flybe considers introducing a means of disseminating pertinent safety information to ground operations staff in an appropriate format.

UPDATE 12 February 2019: A Jazz Dash 8 Q400, C-GGMU, lost a panel on take off from Toronto-Pearson International Airport (CYYZ) on 25 January 2019.

During the takeoff from CYYZ, the left-hand engine cowl door separated from the nacelle and struck the left wing leading edge, causing damage to the de-icing boot.

…maintenance had performed a pre-flight inspection before the departure from CYYZ, which included engine oil quantity checks in the area of the missing cowl.

UPDATE 9 October 2020: Transport Canada have issued Civil Aviation Safety Alert (CASA) No. 2020-08, which includes the information that:

De Havilland Aircraft of Canada Limited has issued an All Operator Message (AOM), No. 870 on 17 July 2020, to bring attention to a new Aircraft Maintenance Manual (AMM) task instruction for proper cowl door closing, the Service Bulletin 84-11-46, a new modsum which introduces placards for illustrating the proper closing of the cowl door, and new rework modifications to improve the ability of latch engagement.

Other Safety Resources

- BA A319 Double Cowling Loss and Fire – AAIB Report

- BA A319 Double Cowling Loss and Fire – AAIB Safety Recommendation Update

- ANSV Report on EasyJet A320 Fan Cowl Door Loss: Maintenance Human Factors

- Tiger A320 Fan Cowl Door Loss & Human Factors: Singapore TSIB Report

- United Airlines Suffers from ED (Error Dysfunction)

- James Reason’s 12 Principles of Error Management

- Back to the Future: Error Management

- UPDATE 11 March 2018: EC120 Forgotten Walkaround

- UPDATE 24 June 2018: B1900D Emergency Landing: Maintenance Standards & Practices The TSB report posses many questions on the management and oversight of aircraft maintenance, competency and maintenance standards & practices. We look opportunities for forward thinking MROs to improve their maintenance standards and practices.

- UPDATE 25 August 2018: Crossed Cables: Colgan Air B1900D N240CJ Maintenance Error On 26 August 2003 a B1900D crashed on take off after errors during flying control maintenance. We look at the maintenance human factor safety lessons from this and another B1900 accident that year.

- UPDATE 10 November 2019: Tight Cable Tie Nose Gear Jam

- UPDATE 12 October 2020: Runaway Dash 8 Q400 at Aberdeen after Miscommunication Over Chocks

- UPDATE 22 October 2020: Dash 8 Q400 Control Anomalies: 1 Worn Cable and 1 Mystery

- UPDATE 25 March 2023: Managing Interruptions: HEMS Call-Out During Engine Rinse

- UPDATE 29 July 2023: Missing Cotter Pin Causes Fatal S-61N Accident

UPDATE 16 October 2018: Russian officals have attributed to procedural failure the loss of an engine door on a Bombardier Q400 shortly after departing Vladivostok.

Rosaviatsia…says the nature of the locks enabled a “false” closure, and that the work – performed in low light – was not subsequently checked. Nor was the oversight detected during the preparation of the Q400 for departure.

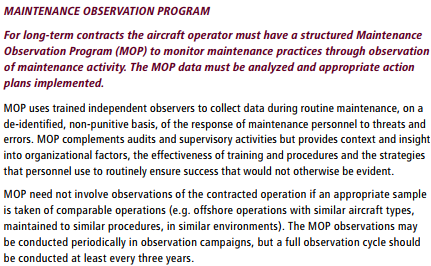

Aerossurance worked with the Flight Safety Foundation (FSF) to create a Maintenance Observation Program (MOP) requirement for their contractible BARSOHO offshore helicopter Safety Performance Requirements to help learning about routine maintenance and then to initiate safety improvements:

Aerossurance can provide practice guidance and specialist support to successfully implement a MOP.

Aerossurance is pleased to sponsor the 9th European Society of Air Safety Investigators (ESASI) Regional Seminar in Riga, Latvia 23 and 24 May 2018.

Aerossurance is pleased to be both sponsoring and presenting at a Royal Aeronautical Society (RAeS) Human Factors Group: Engineering seminar Maintenance Error: Are we learning? to be held on 9 May 2019 at Cranfield University.

Recent Comments