Too Extreme: Fatal Sky Combat Ace EA300 Aerobatic Accident (N414MT)

On 21 October 2017 Extra EA 300/L N414MT of California Extreme Adventures, doing business as Sky Combat Ace (SCA), impacted the ground near El Capitan Reservoir, near Four Corners, California. The pilot and passenger were fatal injured, the aircraft destroyed and a brush fire triggered. The aircraft had departed Gillespie Field (SEE), El Cajon, San Diego, California in visual meteorological conditions 15 minutes earlier.

Sky Combat Ace

The US National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) explain in their safety investigation report (issued 13 July 2020) that this flight was classified as a Part 91 instructional flight but:

SCA’s website described itself as an “extreme aviation attraction,” providing a series of aviation-related experiences, which it described as including aerobatics, air combat, and flight training. The accident flight was a 25-minute “Top Gun” experience… SCA provided flights to its passengers by operating as a flight school under the auspices of 14 CFR Part 61 and using flight instructors to provide training. Review of the SCA presence on multiple social media platforms revealed that it both presented itself and was categorized in the “tour” category.

SCA are certainly popular looking at their TripAdvisor reviews.

One pilot, who was initially the director of training and then director of flight operations, stated that, of about 2,000 customers he had flown for SCA, about 12 to 15 were pilots looking to receive targeted flight training for either upset recovery or a tailwheel endorsements. The other pilot stated that of the 500 customers he had flown, about 6 were pilots seeking tailwheel endorsement training and the others were customers seeking “experience” missions.

On arrival customers who had booked a flight experience were required to sign a “Participant Agreement Release and Assumption of Risk” waiver and take part in a briefing session. It’s not clear if they were done in this order.

The Accident Flight

The pilot, who had been hired by SCA in May 2017, had flown around 4290 flying hours in total, 113 in the EA300. The day before he had flown as a commercial passenger to SCA’s Henderson (HND), Nevada base. He slept on the couch in at SCA’s the crew accommodation (all the beds were taken). The NTSB say that:

About 1000 on the morning of the accident, the pilot flew a customer on a group combat mission from HND in an Extra 300 airplane. He then flew back to the SEE facility in the accident airplane with the company’s director of marketing. The accident flight was his third flight of the day.

The passenger…had had flown with SCA on a similar flight in December 2015 out of SCA’s HND location.

NTSB note that:

The airplane had g limitations in the aerobatic category of +/-10 g. This limit was only allowed with one person onboard, at a MTOW of 1,808 lbs. In a two-person configuration, the limits were +/-8 g at 1,918 lbs MTOW and +/-6 g at 2,095 lbs MTOW. …the airplane’s weight on the accident flight would have been about 2,061 lbs.

According to the president of SCA, g-forces are limited to 6 g with passengers onboard, and airspeed is limited to 180 knots.

However, (emphasis added):

The “Standards and Syllabus” stated that, in order to minimize wear and tear on the aircraft, all aerobatic flights would “strive” to remain at or under 6 g and that aerial dogfighting would be allowed up to 8 g.

The NTSB describe the flight as follows:

Ground-based radar tracking data provided by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) indicated that the airplane departed from runway 17 at SEE [at 1557] and initiated a climbing left turn, reaching a transponder-reported altitude about 4,700 ft mean sea level (msl) about 5 nautical miles (nm) northeast of the airport. For the next 10 minutes, the airplane followed a track northeast along the general path of the San Diego River, then east of the El Capitan Reservoir and north toward the town of Four Corners.

Sky Combat Ace (SCA) Extra EA300 N414MT Route to El Capitan Reservoir, Four Corners, CA on Avvident Flight (White Dots) with Previous Flights by the Same Pilot Marked Too (Credit: NTSB)

The track depicted a meandering path at varying airspeeds and altitudes between 4,300 and 6,300 ft msl in a manner consistent with aerobatic maneuvers. Multiple witnesses along the route reported seeing an airplane performing aerobatic maneuvers about the time indicated by the radar data.

At 1610, the airplane was about 15 nm from SEE and just north of the reservoir. It then began to track back to the southwest, climbing from 5,000 ft msl to 6,900 ft msl over the next 90 seconds. About 15 seconds later, the last radar return was recorded at the northern edge of the reservoir at an altitude of 3,800 ft msl (about 3,000 ft above ground level).

A glider pilot who passed near the aircraft was interviewed, but she saw nothing of concern. Three witnesses on the ground subsequently saw the aircraft descending. Two saw it disappear from view and then noticed smoke appearing. The third heard an impact.

The Safety Investigation: Debris Analysis

The debris field and wreckage distribution indicated that the airplane impacted the ground in a near-vertical attitude at high speed. The airplane was heavily fragmented during the impact, but remnants of all flight control surfaces were found within the immediate vicinity of the accident site.

Accident Site of Sky Combat Ace (SCA) Extra EA300 N414MT near El Capitan Reservoir, Four Corners, CA (Credit: NTSB)

The airplane was subject to two service bulletins (SB) pertaining to the flight controls, neither of which had been performed. The first required replacement of the rudder cable to prevent premature failure, however the airplane’s rudder cable did not display evidence of failure in the area documented by the SB. The other SB required the addition of a safety clamp to the transponder after a report that a transponder had slid out of its rack and jammed against the pilot control stick during aerobatic maneuvers.

Post impact examination did not reveal any anomalies with the airframe or engine that would have precluded normal operation; however, due to the extensive damage sustained during impact, such anomalies could not be ruled out.

The Safety Investigation: Video Analysis

Although FAA radar data was available, its sample rate meany it did not provide the fidelity necessary to determine the aerobatic manoeuvres being undertaken.

An aft-facing GoPro Hero camera had been mounted at the bottom of the canopy.

The camera was ultimately found 2 years after the accident between the main impact crater and the debris field and it proved very revealing. The NTSB analysed the data:

The unit had recorded video and audio data of the entire flight, from the time shortly after the passenger boarded to the camera’s separation from the airplane and its impact with the ground. The camera recorded ambient cabin audio, and was not connected to the radio or intercom.

The camera was mounted on the centerline of the airplane, facing the front seat, and had a view of the passenger’s upper body and head. The upper 2/3 quadrant of the camera frame had a clear view outside of the canopy, and intermittent and distorted reflections of the pilot’s head could be seen in the canopy throughout the flight. The forward canopy lock and outboard tips of the horizontal stabilizer were visible.

When the recording began, the airplane was on the ground with the canopy open…

Of concern is that…

As the canopy came down, the passenger came in to view. His seatbelt shoulder adjusting strap was fully extended, such that the seatbelt harness was loose around his shoulders and chest. The passenger’s headphones were equipped with a Velcro chin strap, which was not secured, and remained unsecured for the entire flight.

The NTSB provide no information on the passenger briefing process or how passenger were supervised boarding or checked pre-flight. The BEA-Etat (BEA-E), the investigation body for French state aircraft accidents published a safety investigation report into a 2019 uncommanded ejection of a passenger from a Dassault Rafale fighter during high g manoeuvres when they had not been adequately strapped in.

NTSB examined the video of the flight:

The engine start, run-up, taxi, and departure proceeded without any indication of anomalies, and the aerobatic maneuvers began about 6 1/2 minutes after takeoff. The maneuvers continued for about 7 minutes, during which the airplane performed what appeared to be a series of roll, hammerhead, and tailslide maneuvers. The passenger appeared to be manipulating the control stick during some of the maneuvers, while the pilot either lifted both of his hands free of the control stick, or rested them on the top of the center instrument console. The maneuvers were all initiated at similar altitudes, and on multiple occasions the passenger looked outside of the airplane in a manner consistent with scanning for traffic.

After the pilot completed what appeared to be a tumble maneuver, he could be heard saying, “how’s that?” to which the passenger replied, “that was awesome.” Over the next 50 seconds, the airplane regained altitude in a series of climbing turns ending in level flight. At this time, the passenger was not holding the flight controls and appeared to be bracing his arms against the sides of the airframe. The nose of the airplane then pitched up to 45°, and the airplane rolled 90° to the right. The nose began to drop as the roll continued to about 130°, then the direction of roll suddenly reversed, the pilot made a “whooping” sound, and the airplane transitioned into what appeared to be an inverted spin. The passenger appeared to rise up in his seat, and reached up with his right arm up to secure the headphones which were pulling away from his head.

The nose of the airplane then dropped as the spin progressed. After about one revolution, the right wing dropped, and the direction of rotation reversed. After entry into the reversal, the rate of rotation began to increase, and only the sky was visible through the canopy. The wind noise began to increase markedly, and a gap appeared at the right-side canopy frame junction with the fuselage, which is consistent with the airplane approaching Vne.

The passenger began to rock from side to side while forced up against his shoulder straps as the sun came into view on the left side. The sun transitioned to the right side while the rocking movement continued…indicating the airplane was no longer tumbling and its attitude had stabilized. During the final maneuver the passenger was smiling and made “yelping” sounds.

Up until this point, the passenger appeared to be enjoying the flight, but his facial expression changed, and he looked down and reached forward with his right hand. At that moment, the pilot activated the canopy release handle and the canopy opened. The camera was ejected, and continued to record as it descended to the ground, capturing the airplane collide with terrain 6 seconds later. The camera impacted the ground about 26 seconds after the canopy opened.

NTSB comment that:

The violent rocking movement experienced by the passenger in the final seconds did not correspond to the gradual movement of the sun in the canopy, and was likely a result of the pilot applying rapid control inputs, possibly to the rudder, in an attempt to regain airplane control. The pilot released the canopy very shortly after the rocking movements began, so it is likely that he quickly deduced that recovery was not possible and that a bailout was necessary. The collision with terrain happened so fast after canopy release that a successful bailout was unlikely. Both occupants’ seat belts were found in the latched and locked positions, further indicating that they did not have enough time to egress the airplane.

The video did not reveal any evidence of bird strike, fire, canopy failure, or flight control separation, and the passenger appeared to be conscious throughout the entire recording. Sound spectrum analysis revealed that the engine was operating within its normal operating speed range prior to the canopy opening.

The passenger’s seatbelt harness was loose throughout the flight, and he could be seen moving up, down, and forward throughout the maneuvers, with particularly accentuated movement during the maneuver leading up to the accident. The position of his feet during the final maneuver could not be determined, however, inadvertent flight control interference could not be ruled out as he braced himself against the effects of the negative g-forces while secured with a loose seatbelt.

The Safety Investigation: FAA Regulations and Regulatory Oversight of Sky Combat Ace (SCA)

NTSB comment that:

Federal Aviation Regulations require commuter and on-demand operators to be appropriately certificated under 14 CFR Part 135; as such, their operations, pilots, and aircraft are subject to FAA regulations and oversight that exceed that of Part 91 operations. Part 135 also prohibits passengers from manipulating the flight controls, and FAA guidance generally does not allow anyone operating under Part 91 to advertise their services, however, exceptions exist for flight training.

The operator presented itself as a 14 CFR Part 61 flight school, and although they did provide upset recovery and tailwheel endorsement flight training and all the company pilots held flight instructor certificates, the vast majority of customers (including the accident passenger) did not hold any type of pilot certificate, and purchased flights for the aerobatic and air combat experience. Further, the operator’s facilities were outfitted with equipment to host parties, including a bar, dart boards, pool tables, and basketball hoops. The company’s website and sales literature was clearly directed toward the adventure and experience side of the business and contained numerous references to sightseeing. The operator employed a marketing director and actively advertised its services, often to groups, for corporate events and birthday, retirement, and wedding celebrations. Very little of the advertising was related to traditional flight training.

The operator’s president stated that he had conferred with the FAA and made attempts to identify the appropriate operations category, and it was on that basis that he had chosen to establish the company as a Part 61 flight school operation. Limited FAA oversight exists for Part 61 operations, and there are essentially no regulations specifically tailored for the certification and comprehensive oversight of the “adventure flight” category that the company was essentially operating under.

Therefore, by operating as a Part 61 flight training provider, the company was able to advertise its services, expose fee-paying passengers to high-risk flight profiles, while circumventing the regulations and oversight for operators who provide transportation for compensation or hire.

In other words SAC were operating in a relative regulatory vacuum with little oversight. This is not the only such US accident in recent years where the operating rules have been suspect. One example involving Airbus Helicopters AS350B2 N350LH is covered here NTSB: Fatal FlyNYON flight was exploiting ‘loophole’ in regs and a detailed NTSB report.

The FAA also allow local air tour flights within 25 statute miles of the departure airport under Part 91.147, a rather basic requirement with few obligations compared to Part 135. We’ve previously written about two fatal local tours from 2016:

- NTSB Reveal Lax Maintenance Standards in Honolulu Helicopter Accident (Bell 206B3 N80918) Shocking maintenance standards prior to an air tour accident in which a 16 year old boy died and his parents were seriously injured

- Torched Tennessee Tour Trip (B206L N16760) An ungreased fuel pump spline failed, the aircraft crashed and suffered a fatal post crash fire.

The regulatory vacuum in which SCA were operating is worrying in light of what the NTSB reveal about the company’s prior safety performance…

The Safety Investigation: SCA’s Past Accidents

SCA had four other accidents in the previous 3 years.

- 26 October 2014 EA 300/L N763DT experienced an in-flight rudder cable separation after recovering from an aerobatic manoeuvre due to wear damage. During the emergency landing it sustained substantial damage after a runway excursion.

- 5 November 2014 EA 300/L N369XT experienced a loss of engine power while on final approach to HND, landing short of the airfield sustaining substantial damage. Fuel was present in the centre and left wing fuel tanks but that the right wing fuel tank was empty. No mechanical anomalies were observed, and the reason(s) for power loss were not determined.

- 30 April 2016 EA 300/L N330MT, was destroyed when it impacted terrain about 10 miles south of HND. The pilot and passenger were fatally injured. The pilot then performed a planned low-level simulated bombing run during which the aircraft struck a hill. Toxicology testing of the pilot detected tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the primary psychoactive component of marijuana. There is a further backstory in this press report: Bachelor party turns tragic after guys fly in stunt planes to avoid forfeiting fares

The first two NTSB investigations did not query the regulatory status of the flying being undertaken. The third quoted an August 2017 FAA legal interpretation, requested in Feb 2017. It stated that various air experience scenarios were not considered to be flight training. It’s not clear what was done with this information prior to the October 2017 fatal accident.

Additionally, SCA was involved in one accident that was not reported to the NTSB or FAA. In September 2016, an EA 300/L, N466MD, experienced a failure and near-total separation of the windshield during aerobatic maneuvers. A video of the event provided by SCA revealed that, while pulling out of the bottom of a loop, the pilot allowed the airplane to exceed its Vne speed (220 knots) and the canopy plexiglass fractured and separated from its frame. The pilot was able to fly the airplane back to the airport with most of the canopy missing. The separation of the canopy adversely affected the performance and flight characteristics of the airplane, and, as such, met the definition of substantial damage; therefore, this event met the definition of an accident [Title 49 CFR Part 830.5].

The operator was also involved in two FAA enforcement actions during the same period, both involving flights with passengers (also discussed here: Sky Combat Ace pilots, aircraft had history of problems before fatal flight).

In one case, a pilot’s certificate was suspended for careless and reckless flying. In another, the FAA concluded that the pilot was likely acting carelessly and sanctioned him with safety awareness counselling.

Again, these do not appear to be isolated cases in light of the NTSB’s analysis of video of previous flights by SCA pilots…

The Safety Investigation: Video Analysis of SCA Pilots’ Past Flying

Review of onboard video from 8 of the the accident pilot’s recent flights…

…revealed that, although considered to be a mentor and conservative in nature by his colleagues, the pilot routinely flew airplanes beyond their operating limitations (specifically their vertical acceleration, or g limitations) and at speeds very close to the never-exceed speed, all with passengers on board.

During the final phase of three of those flights, the airplane reached 10 g and maximum speeds of 200 and 205 knots. On one flight, the airplane reached 9 g and 200 knots, and during another, the airplane reached 8.5 g and 190 knots. The pilot appeared conscious during the high-g maneuvers. Three of the passengers appeared to pass out during the high-g phases of those flights, with one passenger also passing out twice as the airplane taxied into the hangar at the completion of the mission. As the highest speeds were reached, gaps could be seen along the edge of the canopy frame at the join with the fuselage, with larger gaps on the right side.

Review of footage of other pilots…

…revealed a company-wide pattern of disregard for the airplane’s published operating limitations and the company’s own policies regarding airspeed and g limitations. Because both the accident airplane and other airplanes in the company fleet had been flown beyond their rated g limits, they would have been required to undergo additional maintenance checks. There was no evidence that such checks had ever been performed on the accident airplane; as such, the airplane was likely unairworthy at the time of the accident.

On October 17, another SCA pilot flew the accident airplane in series of “dogfight” missions with two other SCA Extra 300 series airplanes as part of a corporate group event in Florida. Video revealed that at the beginning of the flights, the g-meter limit needles had not been reset and indicated that the airplane had at some point reached 10.5 g. The vertical acceleration during those missions varied between 3 g and 6 g; however, on the final flight of the day, the pilot asked the passenger if she wanted to perform a high-g turn and experience acceleration of 7 to 8 g’s. She responded that she did not want to pass out, and the pilot gave her advice on how to prepare her body for the turn. He then performed a descending turning maneuver, during which the g meter registered 9 g, and the passenger passed out. The recovery was completed about 950 ft agl. The dogfight maneuvers between the airplanes were performed in scattered cloud conditions at altitudes of between 1,500 and 3,500 ft agl, and on multiple occasions the accident airplane passed through clouds. As the other airplanes performed their final maneuvers, another pilot transmitted, “Oh yeah, 8 G’s” over the common traffic advisory frequency.

The degree of passenger interaction with the flight controls varied, with some holding the controls through most of the flight, some touching the controls intermittently, and some showing hesitancy to interact in any form. None of the passengers in the reviewed videos held FAA pilot or medical certificates.

The president of SCA was also an active instructor for the company. He stated that, due to the quantity of video footage produced, he did not review every flight video but instead instructed the video editing team (who were composed of pilots and non-pilots) to bring to his attention any flight maneuvers or operations that could be considered a violation of company policy.

It is not clear how often flights were highlighted to SCA’s President. NTSB conclude:

Both the company’s ineffective internal controls and their ability to operate in an environment where limited FAA oversight existed allowed these behaviors and violations to continue.

Organisational Culture at Sky Combat Ace

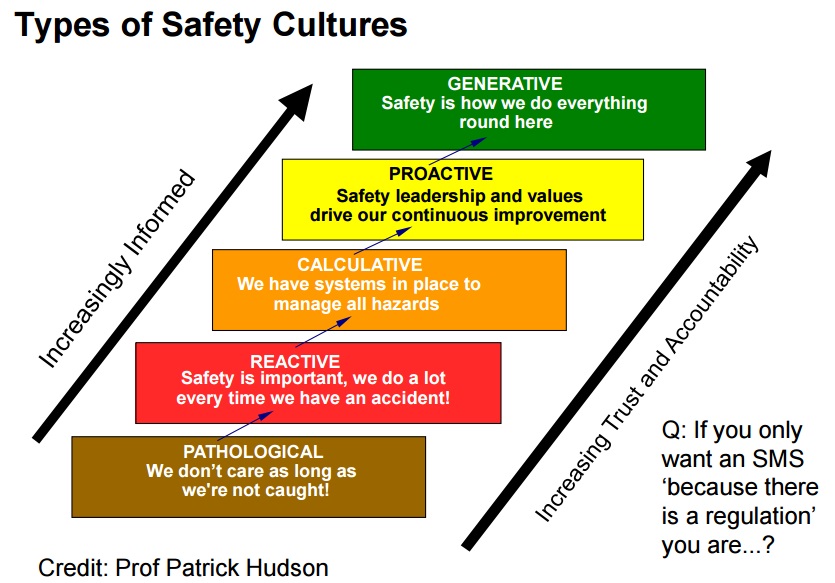

The NTSB don’t specifically use the term ‘culture’ but their conclusion above suggests a cultural problem within the organisation. Prof Patrick Hudson proposed the following model, developed from earlier work by Ron Westrum to describe safety culture:

When discussing this model, Hudson wittily explains why brown was chosen as the colour for the pathological…

SCA flights aren’t cheap. The 25-minute “Top Gun” experience flight currently retails for $699 (including transfer to/from downtown hotels). NTSB explain that:

Interviews with two pilots from SCA revealed that their flying varied based on seasonal loads, but they typically flew four to five customer missions per day, about 5 days per week.

Therefore, one would imagine SCA should be able to pay a reasonable wage to their pilots. However, there is one possible further indication of why an apparent culture of operating aircraft beyond flight manual limits had developed. That can be found in NTSB photographs of SCA EA300 instrument panels that have a non-standard placard prominent in front of passengers:

NTSB Probable Cause

Collision with terrain after the pilot was unable to regain airplane control during an aerobatic maneuver.

Contributing to the accident was the operator’s failure to provide effective internal oversight to identify and prohibit exceedance of the airplanes’ performance parameters, and the lack of regulatory framework available to oversee and regulate such flight operations.

Safety Resources

Video case study of another excessive aerobatic accident with a Piper PA-28 (N55307):

We have written these past accident case studies:

- Survival Flight Fatal Accident: Air Ambulance Operator’s Poor Safety Culture

- Culture and CFIT in Côte d’Ivoire

- RCAF Production Pressures Compromised Culture

- Investigation into F-22A Take Off Accident Highlights a Cultural Issue

- ‘Procedural Drift’: Lynx CFIT in Afghanistan

- All Aboard CFIT: Alaskan Sightseeing Fatal Flight and Safety Culture

- Investigators Criticise Cargo Carrier’s Culture & FAA Regulation After Fatal Somatogravic LOC-I

- Culture + Non Compliance + Mechanical Failures = DC3 Accident

- ‘Competitive Behaviour’ and a Fire-Fighting Aircraft Stall

- Procedural Drift at Saab 340 Operator Leads to Taxiway Excursion

- Execuflight Hawker 700 N237WR Akron Accident: Casual Compliance

- How a Cultural Norm Lead to a Fatal C208B Icing Accident

- Gulfstream G-IV Take Off Accident & Human Factors

- Fatal G-IV Runway Excursion Accident in France – Lessons

- Fatal Night-time UK AW139 Accident Highlights Business Aviation Safety Lessons

- CFIT Gangnam Style – Korean S-76C++ and Decision Making

- That Others May Live – Inadvertent IMC & The Value of Flight Data Monitoring

- US Fatal Night HEMS Accident: Self-Induced Pressure & Inadequate Oversight

- Chernobyl: Lessons in Safety Culture

- Culpable Culture of Compliance?

- A Railroad’s Cult of Compliance

- UPDATE 13 September 2020: Hawaiian Air Tour EC130T2 Hard Landing after Power Loss (Part 1)

- UPDATE 18 October 2020: Hawaiian Air Tour EC130T2 Hard Landing after Power Loss (Part 2 – Survivability)

- UPDATE 17 January 2021: Grand Canyon Air Tour Tragic Tailwind Landing Accident

You may also be interested in these Aerossurance articles:

- How To Develop Your Organisation’s Safety Culture positive advice on the value of safety leadership and an aviation example of safety leadership development.

- How To Destroy Your Organisation’s Safety Culture a cautionary tale of how poor leadership and communications can undermine safety.

- Safety Intelligence & Safety Wisdom

- HROs and Safety Mindfulness

- Consultants & Culture: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly

We also highly recommend this case study: ‘Beyond SMS’ by Andy Evans (our founder) & John Parker in Flight Safety Foundation, AeroSafety World, May 2008, which discusses the importance of leadership in influencing culture.

Aerossurance was to have run workshops at the EHA European Rotors VTOL Show and Safety Conference in Cologne in November 2020 on a) Safety Culture and Leadership and b) Contracting Aviation Services: An Introduction to the Basics. Sadly the show has been postponed due to COVID-19.

Recent Comments