Culture and CFIT in Côte d’Ivoire (ALAT SA342M Gazelle)

On 10 July 2018, Airbus Helicopters (formerly Aérospatiale) SA342M Gazelle 3866 of the French Army 3rd Combat Helicopter Regiment (3e RHC) was completing an exercise with troops of the Armed Forces of Côte d’Ivoire (FACI) 20 km SE of Abidjan, Ivory Coast, when the crew made a loss pass over the troops. The French liaison officer on the ground requested the helicopter conduct a second mock strafing pass.

History of the Flight

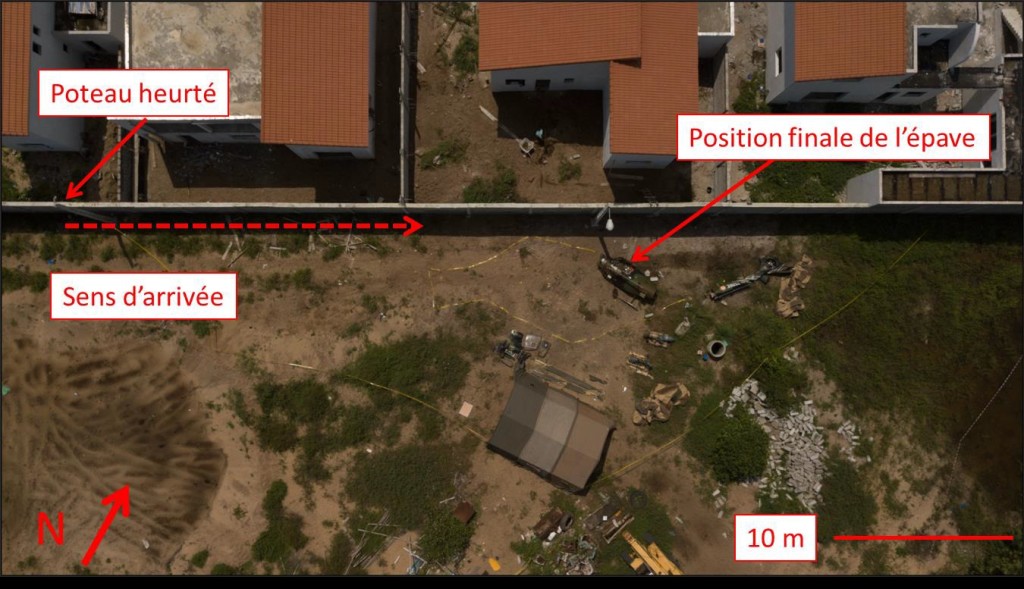

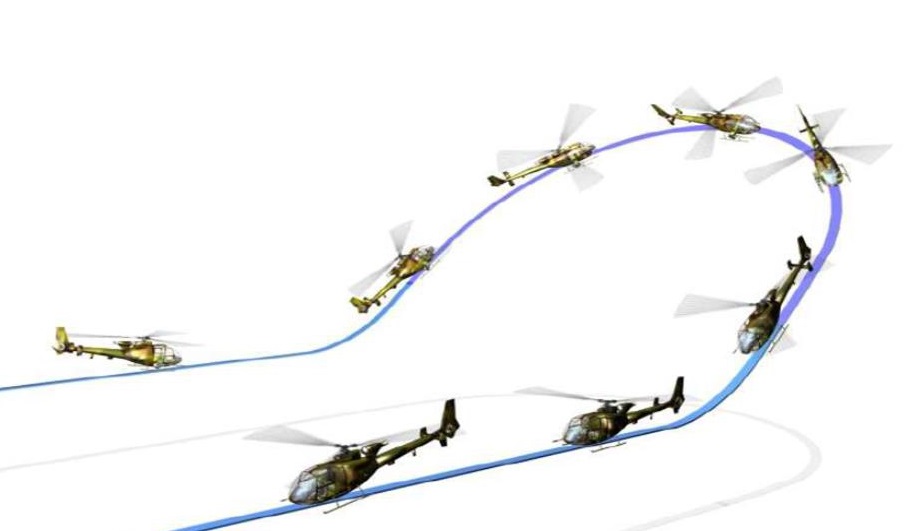

The helicopter had first came from the east and passed the group on the ground at only c65-100 ft before climbing to make a tight turn and decent before a return pass. The aircraft however descended steeply and struck a power line and a pole before impacting the ground. One crew member died and the other was seriously injured in this controlled flight into terrain event (although this would strictly be coded as a Low Altitude [‘LALT’] event in the CAST/ICAO Common Taxonomy).

BEA-E Safety Investigation and Analysis

Investigators of the BEA-Etat (BEA-E) note in their safety investigation report (only available in French) that it is likely the manoeuvre to reverse direction was commenced at too low a speed and started at too low a height (100 kts and 165 ft is recommended).

Furthermore it is likely that the right turn was tighter than recommended, which required more power to be diverted to the fenestron. There was also a 6 kt tailwind during the decent that may not have been considered by the crew. The crew may also have been surprised by reaching the servo reversibility threshold.

The investigators also comment that in 2012 the strafing role was removed from the Gazelle fleet so there had been no recent training in the manoeuvre.

The impromptu manoeuvre was labelled as both a ‘thrill-seeking’ and a ‘routine violation’ by the BEA-E investigators, who note that the exercise had been relatively unstimulating (the local troops had been practicing vectoring the helicopter to a target). Less sophisticated organisations might stop their analysis here or just focus on the culpability of the personnel directly involved. The BEA-E thankfully took a more sophisticated approach.

First they consider the perception of risk.

Both pilots were qualified in tactical flight (leading to a belief in their chances of success) and regularly carry out this type of flight training or operation. The pass below the minimum overflight height did not occur early but late in the session, or after over an hour of evolution of the work area with possibility to recognize and become familiar with the area (belief its ability to control the situation). Finally, it seems that this first pass at a height of less than 165 ft had resulted no comment by the present ground staff, including from the patrol leader on the ground (belief on the look of others).

They comment that group decision-making, compared to individual decision-making tend to focus more on the potential positive benefits and that “young adults, particularly young men are known to be a population with an excess risk of accidents compared to other demographic groups as violation behaviours are more frequent”. Consequently, and entirely predictably:

The group and its demographic and sociological characteristics favored the adoption of risky behaviour.

Less obvious is that the detachment had only recently returned to full strength (3 Gazelles) after a “long period” with just one. This resulted in a increase in flying to clear the backlog of taskings. Working hours were consequently extended and the accident crew had been deployed to Côte d’Ivoire at short notice too. The investigators believe:

The accumulated fatigue..[in] recent weeks may have contributed to inadequate decision-making.

The detachment was also commanded by a relatively junior officer who was also tasked with gaining a FRA-145 military maintenance approval for the unit at the same time adding to their workload.

The investigators say:

The safety culture of an organization is determined by the commitment of operators in safe behavior. It is defined as a set of practices and beliefs shared by the stakeholders of an organization in order to promote safety.

Although formally unauthorized, low flying and unscheduled gun-pass demonstrations seem to be fairly shared practices among some ALAT [Army Aviation] units. The specific organizational culture present within Gazelle helicopter squadrons contributed to the event.

BEA-E Conclusions

The accident was the combination of multiple factors:

- execution of an unplanned, uncontrolled maneuver, performed beyond the aircraft’s capabilities and outside the regulatory framework;

- search for sensation, the desire to demonstrate one’s know-how and assert one’s belonging to the group, and the need for a demonstration of strength;

- feeling of routine associated with a mission considered to be unmotivating, encouraging the search for a rewarding maneuver;

- culture of certain Gazelle squadrons that maintain obsolete know-how;

- short notice between the designation and the departure of the crew on secondment, preventing the pilot in command from measuring the technical capabilities of the pilot;

- exposure of the crew of a certain euphoria of the ground personnel leading to an underestimation of the risks;

- presence of an audience with whom the crew wanted to impress;

- demographic composition of the group [young males];

- fatigue leading to inappropriate decision making;

- combination of the lack of aeronautical experience of the Gazelle helicopter detachment commander and a particular hierarchical gradient;

- absence of initial CRM training for the officer in charge of the training session, particularly in the area of deviation management (error, violation);

- physical and symbolic distance between the detachment commander and the crews of the Gazelle helicopter detachment;

- absence of mandatory monitoring of the Gazelle crews’ skills in implementing evasions;

- misinterpretation of certain messages regarding acceptable safety practices;

- alteration of the safety culture within certain ALAT units that led to a progressive normalization of the deviations.

Other Safety Resources

We have written these past accident case studies:

- RCAF Production Pressures Compromised Culture

- Investigation into F-22A Take Off Accident Highlights a Cultural Issue

- ‘Procedural Drift’: Lynx CFIT in Afghanistan

- All Aboard CFIT: Alaskan Sightseeing Fatal Flight and Safety Culture

- Investigators Criticise Cargo Carrier’s Culture & FAA Regulation After Fatal Somatogravic LOC-I

- ‘Competitive Behaviour’ and a Fire-Fighting Aircraft Stall

- Culture + Non Compliance + Mechanical Failures = DC3 Accident

- Procedural Drift at Saab 340 Operator Leads to Taxiway Excursion

- Execuflight Hawker 700 N237WR Akron Accident: Casual Compliance

- How a Cultural Norm Lead to a Fatal C208B Icing Accident

- Gulfstream G-IV Take Off Accident & Human Factors

- Fatal G-IV Runway Excursion Accident in France – Lessons

- Fatal Night-time UK AW139 Accident Highlights Business Aviation Safety Lessons

- CFIT Gangnam Style – Korean S-76C++ and Decision Making

- Chernobyl: Lessons in Safety Culture

- Culpable Culture of Compliance?

- A Railroad’s Cult of Compliance

- UPDATE 19 May 2020: Survival Flight Fatal Accident: Air Ambulance Operator’s Poor Safety Culture

- UPDATE 4 October 2020: Investigators Suggest Cultural Indifference to Checklist Use a Factor in TAROM ATR42 Runway Excursion

- UPDATE 25 April 2021: A Second from Disaster: RNoAF C-130J Near CFIT

- UPDATE 3 October 2021: French Cougar Crashed After Entering VRS When Coming into Hover

You may also be interested in these Aerossurance articles:

- How To Develop Your Organisation’s Safety Culture positive advice on the value of safety leadership and an aviation example of safety leadership development.

- How To Destroy Your Organisation’s Safety Culture a cautionary tale of how poor leadership and communications can undermine safety.

- Safety Intelligence & Safety Wisdom

- HROs and Safety Mindfulness

- Consultants & Culture: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly

We also highly recommend this case study: ‘Beyond SMS’ by Andy Evans (our founder) & John Parker in Flight Safety Foundation, AeroSafety World, May 2008, which discusses the importance of leadership in influencing culture.

Aerossurance‘s Andy Evans has volunteered to deliver two training sessions at European Rotors on 17 November 2021. Places are still available to book but likely to be unavailable by mid-October so don’t hesitate!

Note: This article is based on our translation of the French original. We are conscious that, there are details of the local command structure, in particular, that may have been lost in translation or indeed might not have been expanded upon in the original.

Recent Comments