Survival Flight Fatal Accident: Air Ambulance Operator’s Poor Safety Culture (B407 N191SF, Ohio)

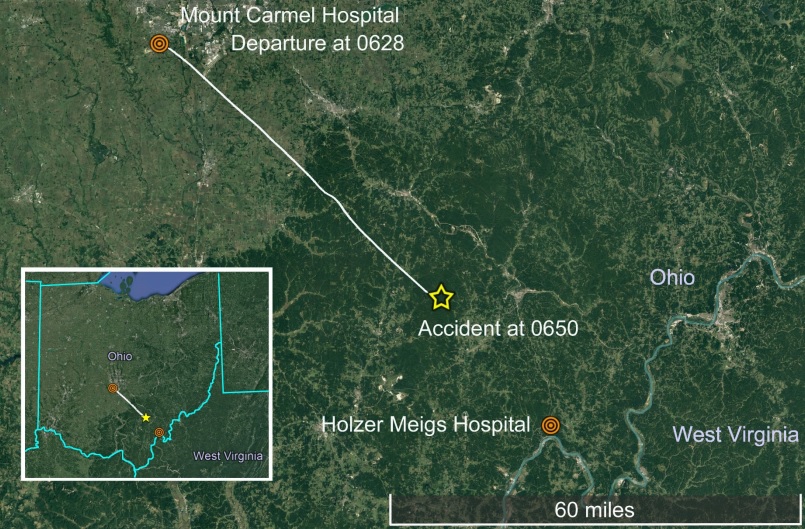

On 29 January 2019, at 0650 local time Bell 407 air ambulance helicopter N191SF, collided with forested rising terrain about 4 miles NE of Zaleski, Ohio. The pilot, flight nurse, and flight paramedic were all fatally injured and the helicopter destroyed.

The helicopter was operated by Viking Aviation doing business as Survival Flight (not to be confused with Survival Flight University of Michigan Metro Aviation). The flight departed Mt. Carmel Hospital, Grove City, Ohio at 0628, destined for Holzer Meigs Hospital, Pomeroy, Ohio, about 69 miles SE.

The Accident Flight

The US National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) say in their safety investigation report, abstract and 2,600 page public docket that Holzer Meigs Hospital had first contacted MedFlight, another helicopter air ambulance operator, for the patient transport flight at 0601. MedFlight refused the flight due forecast icing and snow. The hospital next contacted HealthNet Aeromedical Services. HealthNet said they would perform a “weather check” and get back to the hospital. After the call with HealthNet, the hospital contacted Survival Flight, a relatively new operator in the area since June 2018, who accepted the flight within 3 minutes (HealthNet subsequently called back to turn down the flight after 6 minutes studying the weather). This is a practice called ‘Helicopter Shopping‘ (see below).

According to the Survival Flight Operations Control Specialist (OCS) on duty at the time of the accident at the Survival Flight Operations Control Centre (OCC) in Batesville, Arkansas, the hospital did not mention MedFlight had turned down the flight and there were no entries in a website called weatherturndown.com (see below). They also explained that it was the night shift pilot who had accepted the flight (in just 28 seconds)…

…while he was on the phone with that pilot reviewing flight details about 0612, he was told that, due to the upcoming shift change, the day pilot would be taking the flight [they were en route by car and 5 minutes away].

The night shift pilot, who had been awoken by the OCS…

…asked the accident pilot while she was driving to the helicopter if she needed anything. He had already briefed the accident pilot concerning the flight request and the accident pilot had told him she already had her helmet and knee-board with her.

Twilight would start at 0710 with sunrise at 0739.

He asked if she needed the night vision goggles (NVGs) and she told him that she did not. He then notified the medical crew that there was a flight request and proceeded to the helipad to prepare the helicopter. By the time the accident pilot arrived he had the helicopter started and was preparing to program the waypoint information into the navigation system. He handed the accident pilot the pilot phone and she boarded the helicopter. He then returned to the base.

It appears no pre-flight risk analysis form was completed (see below). The pilot did have an iPad but the NTSB could not determine if she checked the weather herself.

OCC recordings indicated at 0625, the accident pilot contacted the OCS via onboard satellite radio to confirm the destination for the flight. At 0627, the accident pilot again called the OCS, but this time to request the coordinates of Holzer Meigs Hospital. At 0629, the OCS called the accident pilot requesting her flight release information. She replied with her flight risk assessment, “I’m green all categories.” The last communication between the accident pilot and OCS occurred during an exchange at 0630, at which time the accident pilot requested patient information.

The OCS said that, while watching the helicopter on flight tracking software in the Operations Control Center, he observed that, about 15 minutes after departure, the helicopter made a turn to the right, then “a sharp left turn,” which was immediately followed by a “no-tracking alarm.” The emergency action plan was then initiated.

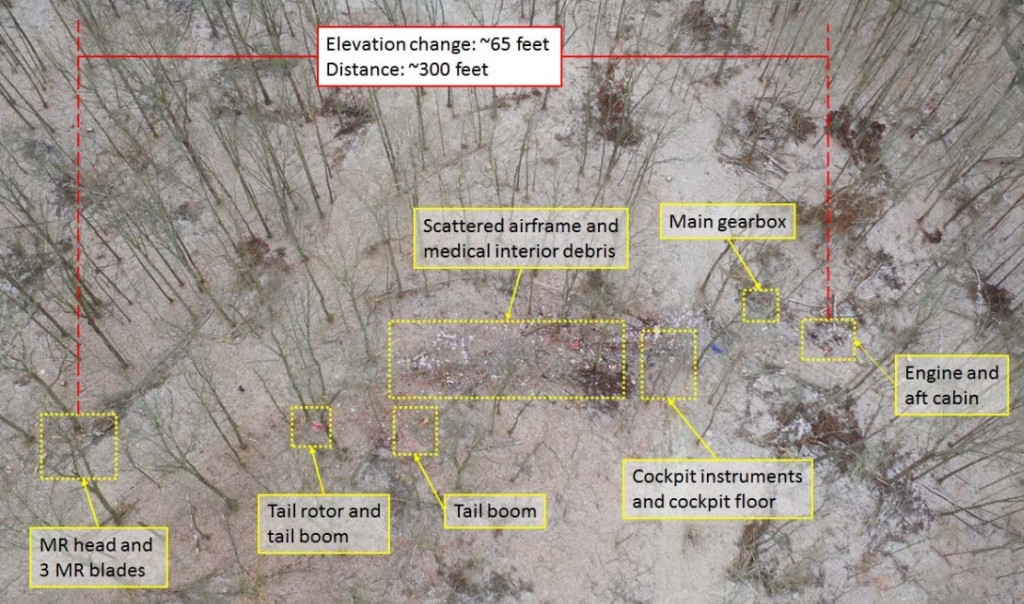

The wreckage was located subsequently in woodland and debris path extended about 600 ft.

The Accident Investigation

The Accident Sequence

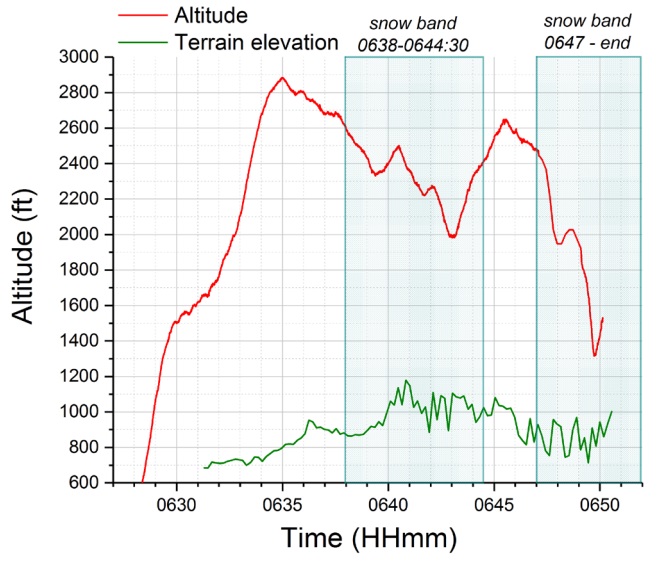

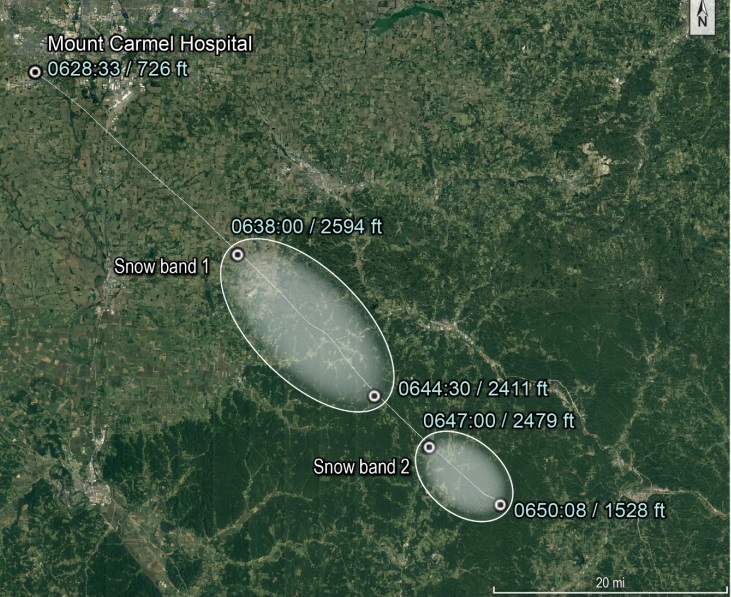

The helicopter was flying mostly between 900 and 1,700 ft above ground level as it traversed the first of two bands of snow showers. The aircraft descended around 600 ft.

During a second encounter with snow several minutes later, which would have significantly reduced visibility, the pilot made a left 180° turn.

During the encounter with the second snow band, the pilot likely encountered instrument meteorological conditions (IMC) due to reduced visibility in snow. Shortly after the encounter with the second snow band, the helicopter flew a path consistent with a 180° descending left turn, which may have indicated the pilot was attempting to perform an escape maneuver to exit inadvertent IMC [in keeping with standard operating procedures]. However, she did not command the helicopter to climb, and it continued to descend until the last moments of the flight. The helicopter impacted trees on the reciprocal heading of the flightpath.

Investigators do not believe the aircraft had been affected by icing.

Meteorological Data

NTSB say:

On the morning of the accident, station models around the accident site indicated marginal visual meteorological conditions with gusty surface wind from the west between 10 to 20 knots. Visibilities were reported as low as 3 miles at the surface in light snow conditions. There was a 30% to 60% chance of light snow and two airmen’s meteorological information advisories had been issued; one for moderate turbulence below 10,000 feet mean sea level (msl) and one for moderate icing conditions below 8,000 feet msl.

Although sufficient information was available to the evening shift pilot and the operations control specialist to identify the potential for snow, icing, and reduced visibility along the accident flight route, their failure to obtain complete en route information precluded them from identifying crucial meteorological risks for the accident flight.

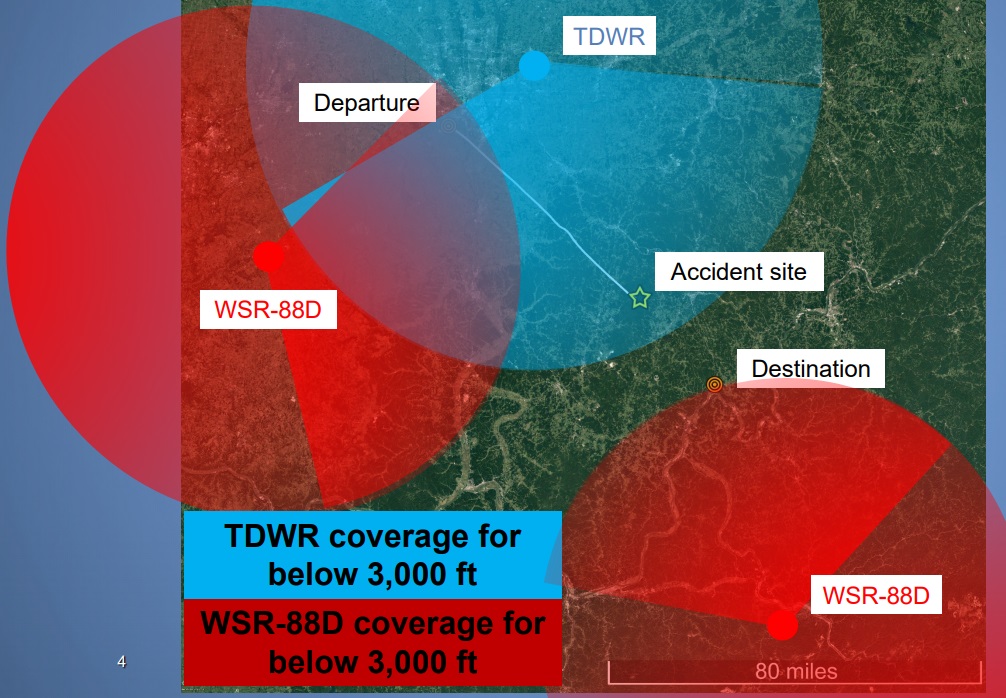

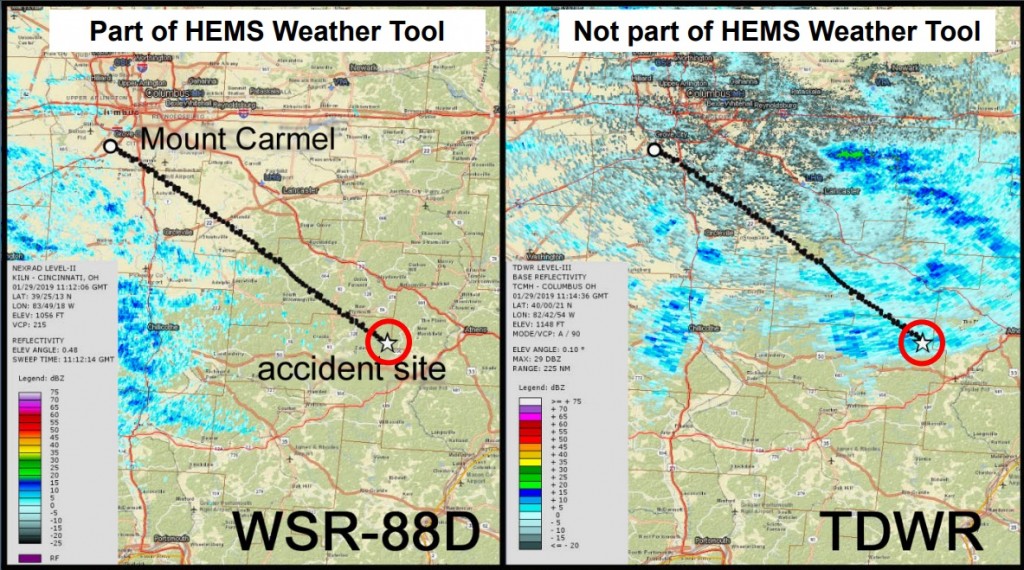

The NTSB meteorological expert believes the Survival Flight personnel made only a basic examination of the met data on the HEMS Weather Tool, using the default settings and, for example, did not overlay available icing data. Furthermore this tool relied on two National Weather Service (NWS) WSR-88D radars whose coverage at 3000 ft is shown in red.

An FAA TDWR radar however gave much improved low level coverage along most of the route but did not feed into the HEMS Weather Tool. If it had there would have been a more dissuasive weather picture at the time the flight was accepted:

The availability of the lower-altitude reflectivity echoes from terminal doppler weather radar data on the HEMS Weather Tool radar overlay would have provided awareness to the operations control specialist, the evening shift pilot, and the accident pilot of the potential for snow along the flight route.

Without specialized experience or knowledge of an area, users of the HEMS Weather Tool may not be able to determine if the absence of a weather radar return in a particular area is due to a lack of precipitation or a limitation in radar coverage.

UPDATE 26 October 2020: More on this matter can be found here: Examining the weather radar issues behind the Survival Flight crash

Helicopter Shopping and Reverse Helicopter Shopping

Helicopter shopping is when a hospital contacts multiple Helicopter Air Ambulance (HAA) operators until one accepts a flight request. Typically the hospital start with their usual provider before calling further afield. FAR 135.617 Pre-flight risk analysis requires HAAs to establish a procedure for determining whether another HAA operator has declined the flight request. A website called weatherturndown.com describes itself as “a free service allowing medical transport programs to share current information regarding delays or cancellations due to weather” and was used in the OCC at Survival Flight.

During interviews of current and former Viking Aviation [Survival Flight] employees, some expressed concern that staff at the OCC were using the website weatherturndown.com to obtain flight requests for HAA flights that other operators had turned down due to weather. Several…referred to this a “reverse helicopter shopping”. One pilot stated, “they specifically told me, hey, we were looking at weather turndown and there’s one that was turned down out of Pittsfield, Illinois, we were going to call that hospital and see if you wanted to take it.”

The staff at the Holzer Meigs Hospital [however] were not aware of Survival Flight ever initiating contact for a flight.

The employee perception that their company would engage in reverse helicopter shopping is what is of interest here, even if the company didn’t do such a thing.

Pilot Experience and Training

…records indicated that the pilot had 1,855 hours total flight experience, including 589 hours in turbine helicopter, 1,125 hours in piston helicopter, 264 hours at night, 104 hours of instrument flight experience, and 14.9 hours experience in Bell 206 helicopters prior to her employment. There was no record of the pilot having experience in Bell 407 helicopters prior to her employment with Survival Flight.

The pilot received initial new hire training which included ground and flight training from the operator beginning April 23, 2018 through April 27, 2018, culminating in the satisfactory completion of an Airman Competency/Proficiency Check in a Bell 206 helicopter on April 27, 2018.

The training and the subsequent competency check were all performed in Bell 206 helicopters with the exception of differences training for the Bell 407 that was conducted on April 26, 2018. No competency check was completed in the Bell 407. The Aircrew Training Manual only listed Bell 206 training and noted [incorrectly] that Viking Aviation [Survival Flight] only has Bell 206 helicopters.

Company flight logs for May 2018 through December 2018 indicated that the pilot had flown a total of 94.8 hours, including, about 98 hours in Bell 407 aircraft, 57.2 hours during the day, 16.4 hours at night, and 9.7 hours at night using night vision goggles.

Pilot History Prior to the Accident Flight

The accident pilot was working a schedule of day shifts from 0700 – 1900 since January 23. On January 28, the day prior to the accident, she ended her shift around 1730. Her fiancé stated her activities in the days prior to the accident were routine where she would return home after her shift, make dinner and go to bed. Her last cell phone activity that night was an outbound phone call that ended about 2105.

Because the night shift pilot had arrived earlier the night before as her shift was ending, she planned to arrive earlier for her shift the morning of the accident [which the OCC OCS was not aware of].

She was en route to work when she received a phone call from the night shift pilot at 0612 the morning of the accident.

NTSB indicate that adjustments to the shift pattern after one pilot came in early were not being logged as difference from a flight and duty time perspective.

Witnesses at the base stated that the accident pilot had had a discussion with the vice president of EMS services the day prior to the accident regarding the expanse of hilly terrain in southeast Ohio. In the three months prior to the accident, the accident pilot had consistently written comments on weather and precipitation on shift briefing/debriefing paperwork. Shift briefing/debriefing paperwork also indicated that 3 days prior to the accident, she had made a decision to abort a flight due to isolated weather along their route.

The pilot on shift prior to the accident pilot said “knowing who she is, I am certain that once she got off the phone with me, if she wasn’t looking at weather already, she was certainly checking it …. She would fly with an iPad on her knee. She had ForeFlight on it giving her weather … as well. That was her standard operations…. So I feel pretty confident that she would have seen the weather herself, and she was our safety officer. She was very conservative when it came to flying. She wouldn’t push weather at all. If she felt like it wasn’t a safe flight to take, she absolutely wouldn’t have taken it.”

NVIS Policy

The operator was approved to use a Night Vision Imaging System (NVIS) Night Vision Goggles (NVGs). If not used, the unaided night minima applied.

In an interview with the director of safety and training, he stated that he expected pilots to take the NVGs with them on any night flight, “If it’s dark, take them.” He also stated that during training, “we teach we want them to have them on at night.” When asked if it was a company requirement that pilots wear the NVGs all the time at night, the chief pilot responded “Yes.” [However,] no company policy regarding this requirement for the usage of NVGs was…the GOM [General Operations Manual] at the time of the accident.

No FAA regulation required NVIS for night flights either.

Pre-Flight Risk Assessment

FAR 135.617 requires HAA operators to develop a pre-flight risk analysis worksheet. Furthermore:

Advisory Circular 135-14B stated that “operators should establish procedures for coordination between the pilot and OCS, or other person authorized to exercise operational control, to evaluate flight risk analyses to ensure risk is mitigated to the extent possible or a flight request is declined due to unacceptable risk.”

The AC further states: “A PIC’s decision to decline, cancel, divert or terminate a flight overrides any decision by any and all other parties to accept or continue a flight.”

Bizarrely:

In an interview with the pilot that was going off duty when the accident flight request was received, he stated that the accident pilot would have filled out the risk assessment paperwork when she returned to the base after the flight since the request came in at shift change.

This indicates the forms were being completed purely to comply with the regulation to complete and retain a form, rather than to fulfil the intent to increase flight safety. There were allegedly problems implementing such analyses within Survival Flight with personnel commenting to the NTSB that:

“The problem I’ve always had with it is that operations control won’t allow us to go red on weather”.

and

“I’m calling them [the OCC] and I’m telling them hey, we’re red. No, you’re not [they say], you guys are amber this evening. Well, no, we’re red because it says right here the weather is below our day/night weather minimum… and they won’t let you be red… this is just a microcosm of some of the issues.”

NTSB comment that:

…because of the ineffective flight risk assessment used at Survival Flight, the accident flight was allowed to depart, and the pilot had no knowledge of other operators’ previous refusals of the flight or the potential weather along the route of flight.

Flight Data Monitoring (FDM)

US HAA operators are required to instigate an FDM programme. While they had fitted the Outerlink Global Solutions IRIS system, it was primarily used only as a flight tracking tool.

Thus, Survival Flight had the data to evaluate flight performance and identify other flight deviations due to IMC encounters, which Survival Flight was unaware of. An FDM program would have allowed Survival Flight to proactively identify these safety issues and correct them.

Operator’s Safety Management

The operator did not have a Safety Management System (SMS) nor are Part 135 operators required to have an SMS in the US:

The director of safety and training had held the position for 1.5 years. He reported to the director of operations… [and said] … ultimately, I work directly for him, and I carry out his philosophy and, … his way of doing things. And so, I mention…things to him, and if it’s something that he may want to change, then, … he allows me to maybe discuss it with him, but that’s as far as it goes.” A safety coordinator position existed to support the director of safety and training but was unfilled at the time of the accident. One of the director of safety and training’s responsibilities included overseeing the safety representatives at each base.

The chief pilot stated that “safety is, first and foremost, the most important thing in this company.” The director of operations stated that the intent of the safety program was to have a safety representative at each base that was from Viking who would run the program from “an SMS point of view” where the medical side could participate but they would not be the “safety driver.”

He continued that “the safety program varies from base to base. Sometimes it’s very robust, other times people are not as willing to participate. If you’ve got a strong safety person there, it functions a little better than somebody who’s not as interested.”

Several pilots highlighted a lack of transparency by the company on safety issues.

The chief pilot stated that if anyone had a safety issue, they would report it to their base safety representative first. A subset of pilots and medical crews who were interviewed were aware of an anonymous way to report safety concerns. A majority of interviewees stated they could approach their base safety representative with concerns, where others stated they could call management directly. The [accident base’s] safety representative, the accident pilot, was known as being very approachable and proactive to safety

The safety representative would attempt to solve the issue at their level, and report to the director of safety and training if they were unable to resolve it. The director of safety and training would then attempt a solution himself or coordinate with the chief pilot or the director of operations. The chief pilot also stated that safety issues did not need to be reported through the chain of command for resolution.

While personnel were aware of the ways to report concerns, a number of them were uncomfortable voicing concerns due to fear of reprimand by management and the lack of previous management action on voiced safety concerns. One pilot stated “God forbid I have to turn in a safety form without the owner of the company calling and harassing us.” He further stated that “I could call the director of ops, … and that would go nowhere.” Pilots did not feel like they could call in fatigued because “it would get shot down right away.” Another pilot stated that he was not aware of a way to report safety concerns without “getting himself in trouble.”

When the director of safety and training was asked if he felt pilots were comfortable reporting safety issues, he said that “if the reports I’m getting of these reprimands on shift and stuff is… accurate [see below], then … they’re not comfortable.”

[The director of safety and training] had only received one incident report in the 1.5 years he’s been in the position; this report did not involve the Ohio bases.

NTSB say Survival Flight management exhibited “casual behavior…regarding risk assessment and safety programs”.

Operator’s Safety Culture: A Catalogue of Complaints

During discussions to develop a safety program, the director of safety and training said that when evaluating increasing weather minimums as suggested by the CAMTS [Commission on Accreditation of Medical Transport Systems] guidance, management concluded that since “[they’ve] been operating successfully, why change to somebody else’s standards?”

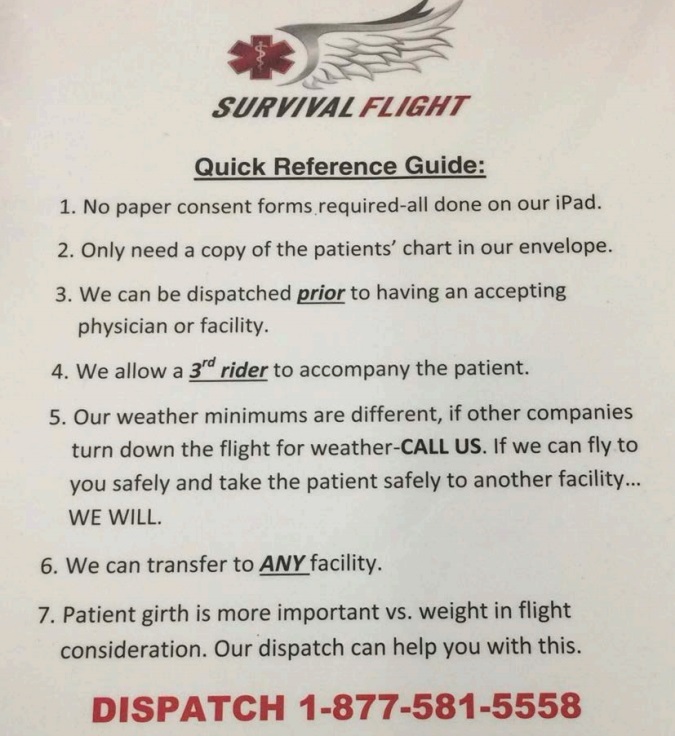

In practice the operator was at best reluctant to exceed the minimum standards set by regulation. At worst they operated to minimums to gain business. The company had issued this Quick Reference Guide:

When asked about Item 5 that stated “Our weather minimums are different, if other companies turn down the flight for weather – CALL US. If we can fly to you safely and take the patient safely to another facility…WE WILL,” the author said “it was her understanding that they operated at minimum FAA weather standards while other companies had raised their minimums, and therefore that allowed them to take flights when other companies could not”.

A pilot…said there was “an awful push to get numbers … it was like they created an environment that felt like a competition, especially when [the accident base] opened up.” Company management motivated bases to conduct flights by purchasing a massage chair for the base if they flew 30 flights in one calendar month. The count of flights per month was kept on the safety board [at the] base. According to the company’s monthly summary, the accident flight was the 26th flight the base would have completed in January.

Pilots and medical crew stated that the company management wanted pilots to be off the pad within 7 minutes of getting a call for a flight. If the aircraft was not off the ground in 7 minutes, pilots were expected to fill out an “occurrence log” to explain to the DO why they didn’t lift off within 7 minutes.

While pilots stated that 7 minutes was “doable” if everything went “smoothly,” several pilots stated that 8-9 minutes was more realistic and highlighted concern with this expectation as the walk to the pad could take upwards of several minutes and would not include time for the 2 minute engine warmup during the winter.

In one case, a pilot was confronted by the base lead pilot for waiting on the pad until all engine temperature gauges were in the green. The lead pilot had told him that there was nothing in the rotorcraft flight manual (RFM) that said to wait for the temperatures to go green and continued that the director of operations had concurred with his (the lead pilot’s) position. In response, the pilot conferred with other line pilots who told him to “just ignore [the lead pilot] and put in a request to ops to include a delay for … engine warmup.”

One pilot stated that the chief pilot “says all the time ‘you know there’s safe weather, there’s legal weather but you need to have both in order to complete the flight.’ …there were numerous company personnel who witnessed people in management, including the chief pilot, pressuring pilots to accept flights.

One pilot described…where a pilot had reported to the OCM [OCC Manager] that he was concerned he was too fatigued to take another flight after flying three already. In this case, the chief pilot, who was OCM at the time, convinced the pilot to accept the flight. The pilot who was interviewed expressed concern about management pressure stating a pilot had already reported that he was tired “ but they try to talk you through it and say hey, … maybe drink a cup of coffee before you go … and try to get it done.”

[N]umerous pilots and medical crew indicated…they were the recipient of or witnessed a pilot being reprimanded or challenged for declining a flight. One medical crewmember said, “the chief pilot of the company… would call within about 10 minutes and would cuss out our pilots and belittle them, … saying, … we need to take these flights,…. he would yell so loud on the phone that you could hear it, … just standing within earshot.” He continued to say that the chief pilot told the pilot that if the base failed, it would be his fault because he was turning down flights.

The director of safety and training stated that several pilots informed him that they were getting reprimands from an operational control manager, specifically the chief pilot. The director of safety and training said that “we don’t need to be pushing people past their comfort level. If they assessed that, and they’re the pilot, they need to have the final say.”

Another example involved a pilot denying a flight for high winds (35 knots gusting 50 knots) and low ceilings. He had received a call from the chief pilot questioning his decision… …he [then] immediately received a call from the director of operations who stated that the aircraft could handle the reported winds. When the DO learned that a medical crewmember was not comfortable, he confronted her “what is this I hear about you not wanting to fly?” She said she explained that it’s not about her not wanting to fly, it was about not wanting to fly this flight after the pilot had already turned it down twice. She further said she didn’t appreciate the pressure he was putting on the crew, and that it shouldn’t happen even after the pilot had said no once. After this conversation, the DO told the pilot to take the flight “or at least try it. If he had to turn around then so be it”.

Several current and former pilots relayed concerns that they were never able to issue a “red” risk assessment and take the base out of service for any reason including, maintenance, fatigue, or weather.

Another pilot stated that they were not allowed to go “red” on the risk assessment when the weather was below minimums. After he told OCC his base was red, they changed his risk assessment to amber. When he pushed back on OCC, he received a call from the director of operations asking “why are you red? that’s not the way we do things.’”

Pilots were concerned that mechanics were feeling pressure to complete maintenance because operations would not accept a “red” risk assessment. In addition, several pilots voiced concerns about management interfering with maintenance decisions. One pilot described an example where an aircraft was hot started at a temperature that required an engine inspection and management refused to allow the inspection. “It was a very hot start, … And it upset [the mechanic]. He refused to put his name on anything regarding the situation and he threatened to quit.” Management offered to allow him to inspect the engine if he chose not to quit, “they opened up the engine and it was damaged.”

Another pilot described pressure he received from the director of safety and training to exceed his maximum 14-hour duty day so the aircraft would not be out of service.

The lead pilot for the base had been with the company since April 2018 and the lead pilot since August 2018.

The company described the base “lead” pilot as an administration role. When asked whether they would expect the lead pilot to be a role model from a safety standpoint, the director of safety and training said “of course… that leadership, that hard one, that lead by example thing… that’s what we try to instill in our lead pilots… But the oversight, … we’re guilty of that. I haven’t been to each base or management doesn’t get to the bases… as often to see them perform.”

The NTSB say:

[A] pilot declined a flight for instrument conditions. The lead pilot confronted him about why the pilot declined and said that the reporting station that was indicating IFR was faulty and that the pilot should have attempted the flight.

In addition:

There had been several concerns brought up to management about his decision making. During a visit by the director of safety and training to the Ohio bases in December 2018, multiple concerns were brought up by the medical crew and base safety officer (the accident pilot) regarding the conduct of the lead pilot.

Significant concerns were documented in a detailed letter to human resources dated December 13, 2019 from the accident nurse.

The letter detailed an event where a flight had been declined by their sister base for low ceilings and weather but was accepted by [their base]. When the nurse expressed concern about bad weather, the lead pilot assured they could conduct the flight “if they hurried.” During flight, the visibility deteriorated, and the nurse expressed concern three more times, however the pilot continued until all visibility was lost.

Another event detailed in the letter discussed a flight where the lead pilot could not use his NVGs and requested the paramedic use his NVGs to talk him through the flight at night over high terrain. The paramedic was uncomfortable with this request because of the limited view he had from his seat. When the nurse looked out the window she only saw “black and a ton of clouds and precipitation.”

Another event mentioned in the letter relates to a flight to Holzer Jackson Hospital. The nurse had noticed “a large area of gray and blue” on the weather map, however when she asked the lead pilot about the weather, he stated it was “all clear” and that they needed to get going. She and the paramedic noted thick snow falling during the flight and the pilot asked the paramedic to use her NVGs to look outside since he could not see through the heavy snowfall with his NVGs.

The DO, chief pilot, and director of safety and training [stated to NTSB] that the problems were not safety related and there were no violations of company policy. The director of safety and training stated that medical crew did not “know as an experienced aviator what ceilings and visibility may or may not be.” In response to the medical crews’ concerns the company “reminded” the lead pilot to stay within weather minimums and sent him to conflict resolution training

NTSB comment that:

Multiple former employees felt that their decisions to voice concerns and deny flights they felt were unsafe played a part in their terminations which occurred shortly afterward. Several former pilots for Survival Flight expressed safety concerns about the operation, however felt that people in the company currently could be reluctant to speak up since they would be “worried for their jobs.”

In conclusion NTSB opine:

Survival Flight’s poor safety culture likely influenced the accident pilot’s decision to conduct the accident flight without a shift change briefing, including an adequate preflight risk assessment.

The NTSB did not however interview the operator’s CEO.

FAA Oversight

Survival Flight has helicopters and fixed wing aircraft. The FAA Principal Operations Inspector (POI) for around 4 years had a fixed wing background and was therefore by FAA policy was also not allowed to observe helicopter flights. A 2015 audit report by the Department of Transportation Office of Inspector General (DOT IG) noted:

FAA hires inspectors rated in commercial airplanes even though some are assigned to oversee helicopter operators. FAA’s inspector qualification standards require experience with single and multiple engine airplanes, not helicopters. However, this focus on larger aircraft experience has left shortages of helicopter inspectors.

With significant foresight they noted that:

…we identified a shortage of helicopter inspectors in four of the seven smaller HEMS oversight offices we visited. Because of the unique operating characteristics of HEMS, inspectors with helicopter experience may be better suited to identify HEMS-specific risks.

In the case of the Survival Flight accident:

The investigation found that, although multiple deficiencies in Survival Flight’s operations were identified postaccident, the principal operations inspector’s previous inspections of Survival Flight did not reveal any deficiencies; the principal operations inspector was unaware of deficiencies that were later identified in Survival Flight’s flight risk assessment.

Safety Issues Identified by NTSB

- Survival Flight’s lack of comprehensive and effective flight risk assessment and risk management procedures.

- The lack of a positive safety culture endorsed [sic] by Survival Flight management and the lack of a comprehensive SMS

- Need for FDM programs for HAA operators.

- Lack of HAA experience for principal operations inspectors assigned to HAA operations.

- Lack of accurate terminal doppler weather radar data available on the HEMS (helicopter emergency medical services) Weather Tool.

- Lack of a [crash resistant] flight recorder.

NTSB Probable Cause

Survival Flight’s inadequate management of safety, which normalized pilots’ and operations control specialists’ noncompliance with risk analysis procedures and resulted in the initiation of the flight without a comprehensive preflight weather evaluation, leading to the pilot’s inadvertent encounter with instrument meteorological conditions, failure to maintain altitude, and subsequent collision with terrain.

Contributing to the accident was the Federal Aviation Administration’s inadequate oversight of the operator’s risk management program and failure to require Title 14 Code of Federal Regulations Part 135 operators to establish safety management system programs.

NTSB Safety Recommendations

NTSB raised 14 new safety recommendations. They reiterated and reclassified two previous recommendations to the FAA and reiterated another two.

NTSB Accident Report (ADDED 8 June 2020)

The final report was issued by NTSB on 8 June 2020.

Survival Flight / NTSB Correspondence (ADDED 20 May 2020)

After the NTSB held their Board Meeting on this accident on 19 May 2020 they uploaded another revealing file to the public docket. First it shows that the NTSB had written to Survival Flight to warn them their ‘party status’ was at risk if they made further public statements speculating on the cause of the accident. The company were promoting the idea of a bird strike, drone strike or gunshot having hit the helicopter (they say this could have caused an unidentified whistling sound recorded near the end of the flight which NTSB sound spectrum analysis suggested was consistent with air blowing into a window opening or similar aerodynamic noise).

It also contains a December 2019 letter from Survival Flight’s lawyers that was also discussed during the NTSB Board Meeting. The lawyers complained that the NTSB’s release of information into the public docket had resulted in customers terminating contracts and difficultly recruiting staff. They also accused the NTSB of pursuing a dispute with the FAA through this investigation. NTSB Chairman Robert Sumwalt commenting that Survival Flight appeared to be “in denial” and said “it does bother me when people accuse us of having an agenda”, urging Survival Flight to heed the NTSB’s recommendations. This was followed by further exchanges between the NTSB and the lawyers.

Survival Flight Statement (ADDED 20 May 2020)

Local media report that the company issued a written statement that:

We’re learning from this tragedy and have already completed five of the NTSB’s six recommendations with ongoing work on the final recommendation, Survival Flight will continue to learn, improve and adapt as a company in order to better serve our communities and save lives.

Another press report suggests the company may well be in denial as their spokesman is quoted as saying:

Nothing in the NTSB report says this was anything other than a tragic accident.

UPDATE 2 July 2020: Survival Flight are closing its two bases in Ohio at Circleville and Marion blamming COVID-19.

Industry Association Statements (ADDED 21 May 2020)

The US helicopter trade association HAI has chosen to challenge the NTSB and have taken the opportunity of this fatal air accident to propose that HAA operators are only selected from operators that HAI themselves accredit (as an alternative to the NTSB recommendation that the FAA actually use helicopter pilots as HAA POIs). Its not clear if they support the reiterated NTSB recommendations for SMS and FDM to be a mandatory requirement for Part 135 operators.

In contrast the Association of Air Medical Services (AAMS) express no objections to the NTSB recommendations. They say that they have supported enhanced regulations for HAA in the past and remain “committed to enhancing the safety of air medical operations and the patients and air ambulance crews that we transport.”

The Flight Safety Foundation (FSF) coincidentally issued a Helicopter Safety White Paper today.

UPDATE 28 January 2021: Lawsuit Alleges Negligence in Fatal Medical Helicopter Crash

Comments on Culture and Safety

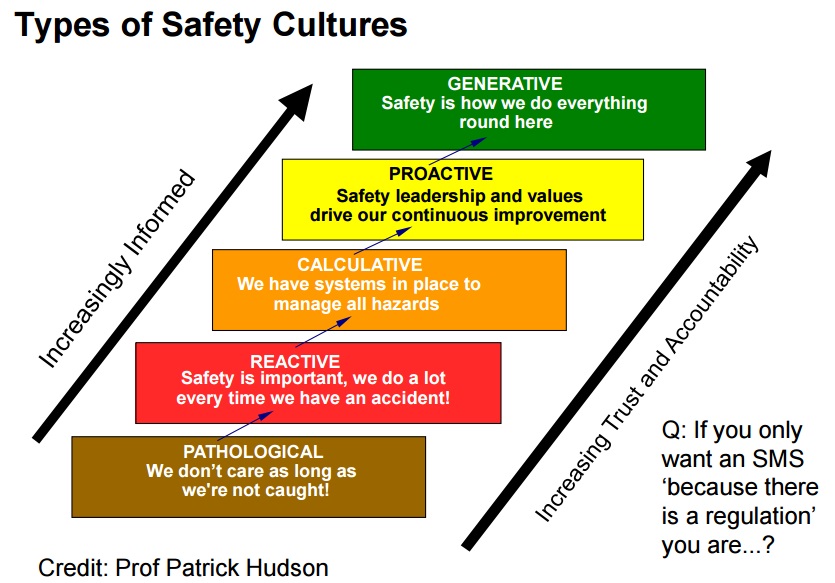

While the NTSB don’t use the term, they imply Survival Flight had a pathological safety culture (Prof Patrick Hudson proposed the following model, developed from earlier work by Ron Westrum):

When discussing this model, Hudson wittily explains why brown was chosen as the colour for the pathological…

Other Safety Resources

We have written these past accident case studies:

- Culture and CFIT in Côte d’Ivoire

- RCAF Production Pressures Compromised Culture

- Investigation into F-22A Take Off Accident Highlights a Cultural Issue

- ‘Procedural Drift’: Lynx CFIT in Afghanistan

- All Aboard CFIT: Alaskan Sightseeing Fatal Flight and Safety Culture

- Investigators Criticise Cargo Carrier’s Culture & FAA Regulation After Fatal Somatogravic LOC-I

- Culture + Non Compliance + Mechanical Failures = DC3 Accident

- ‘Competitive Behaviour’ and a Fire-Fighting Aircraft Stall

- Procedural Drift at Saab 340 Operator Leads to Taxiway Excursion

- Execuflight Hawker 700 N237WR Akron Accident: Casual Compliance

- How a Cultural Norm Lead to a Fatal C208B Icing Accident

- Gulfstream G-IV Take Off Accident & Human Factors

- Fatal G-IV Runway Excursion Accident in France – Lessons

- Fatal Night-time UK AW139 Accident Highlights Business Aviation Safety Lessons

- CFIT Gangnam Style – Korean S-76C++ and Decision Making

- Italian HEMS AW139 Inadvertent IMC Accident

- Norwegian HEMS Landing Wirestrike (Norsk Luftambulanse EC135P2+ LN-OOI)

- EC135P2 Spatial Disorientation Accident

- US HEMS EC135P1 Dual Engine Failure: 7 July 2018

- Misassembled Anti-Torque Pedals Cause EC135P1 Accident

- Austrian Police EC135P2+ Impacted Glassy Lake

- Maintenance Misdiagnosis Precursor to EC135T2 Tail Rotor Control Failure

- That Others May Live – Inadvertent IMC & The Value of Flight Data Monitoring

- Life Flight 6 – US HEMS Post Accident Review

- More US Night HEMS Accidents

- US HEMS “Delays & Oversight Challenges” – IG Report

- Crashworthiness and a Fiery Frisco US HEMS Accident

- HEMS S-76C Night Approach LOC-I Incident

- US HEMS Accident Rates 2006-2015

- HEMS A109S Night Loss of Control Inflight (N91NM)

- Air Ambulance A109S Spatial Disorientation in Night IMC (N11NM)

- US Fatal Night HEMS Accident: Self-Induced Pressure & Inadequate Oversight

- HEMS Black Hole Accident: “Organisational, Regulatory and Oversight Deficiencies”

- Taiwan NASC UH-60M Night Medevac Helicopter Take Off Accident

- EC130B4 Destroyed After Ice Ingestion – Engine Intake Left Uncovered

- Dim, Negative Transfer Double Flameout

- BK117B2 Air Ambulance Flameout: Fuel Transfer Pumps OFF, Caution Lights Invisible in NVG Modified Cockpit

- Chernobyl: Lessons in Safety Culture

- Culpable Culture of Compliance?

- A Railroad’s Cult of Compliance

- UPDATE 4 October 2020: Investigators Suggest Cultural Indifference to Checklist Use a Factor in TAROM ATR42 Runway Excursion

- UPDATE 14 May 2022: Review of “The impact of human factors on pilots’ safety behavior in offshore aviation – Brazil”

- UPDATE 10 June 2023: EC135 Air Ambulance CFIT when Pilot Distracted Correcting Tech Log Error

You may also be interested in these Aerossurance articles:

- How To Develop Your Organisation’s Safety Culture positive advice on the value of safety leadership and an aviation example of safety leadership development.

- How To Destroy Your Organisation’s Safety Culture a cautionary tale of how poor leadership and communications can undermine safety.

- Safety Intelligence & Safety Wisdom

- HROs and Safety Mindfulness

- Consultants & Culture: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly

We also highly recommend this case study: ‘Beyond SMS’ by Andy Evans (our founder) & John Parker in Flight Safety Foundation, AeroSafety World, May 2008, which discusses the importance of leadership in influencing culture.

Recent Comments