A Railroad’s Cult of Compliance

We look at some of the safety culture lessons from a fatal rail accident in the US and how a more sophisticated approach has been taken in the UK.

On 3 April 2016 an Amtrak New York to Savannah express train struck a backhoe construction vehicle near Chester, Pennsylvania supporting track ballast-vacuuming work. The 532t, 278m train had been authorised to operate at the maximum speed (110 mph) despite ongoing adjacent track works. As the train approached the works the driver (or locomotive engineer) saw equipment and workers and applied the emergency brake.

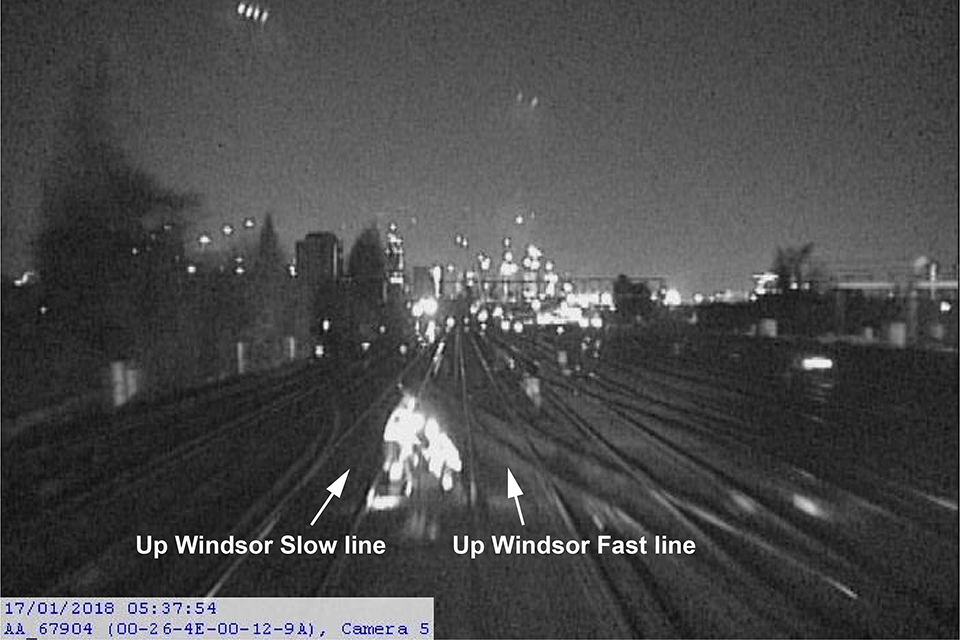

The view from the train’s forward camera, approximately 8.5s before impact as vehicles begin to become visible (Credit: NTSB)

The US National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) in their investigation report say:

The train speed was 106 mph before the emergency brake application and 99 mph* when it struck the backhoe.

[* note some NTSB documents say impact was at 88 mph]

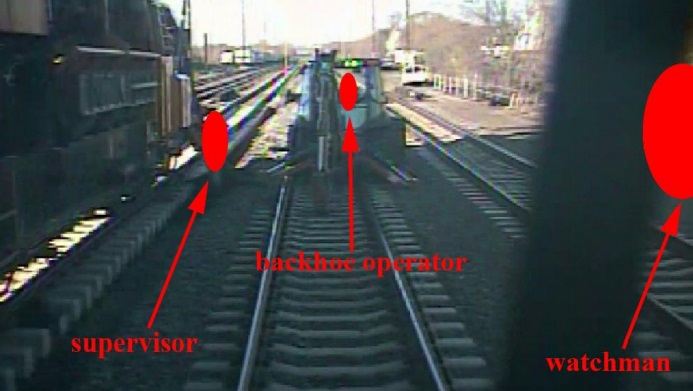

The view from the train’s forward camera, approximately 0.5s before impact at over 100mph, with workers redacted by red symbols (Credit: NTSB)

Two roadway workers were killed, and 39 other people were injured. Amtrak estimated property damages to be $2.5 million.

For comparison: the kinetic energy of the train at impact was equivalent of a backhoe striking a parked train at a near supersonic speed.

The NTSB determined the probable cause was:

…the unprotected fouled track that was used to route a passenger train at maximum authorized speed; the absence of supplemental shunting devices, which Amtrak required but the foreman could not apply because he had none [SSDs are a simple device to connect the two rails and cause the proceeding signal to display STOP]; and the inadequate transfer of job site responsibilities between foremen during the shift change that resulted in failure to clear the track, to transfer foul time [i.e. the time that adjacent tracks would be temporarily occupied during the works], and to conduct a job briefing.

Supplemental Shunting Device (SSD) Forms an Electrical Connection and Indicate the Track is Occupied (Credit: TSB of Canada)

Allowing these unsafe actions to occur were the inconsistent views of safety and safety management throughout Amtrak’s corporate structure that led to the company’s deficient system safety program that resulted in part from Amtrak’s inadequate collaboration with its unions and from its failure to prioritize safety.

Also contributing to the accident was the Federal Railroad Administration’s failure to require redundant signal protection, such as shunting, for maintenance-of-way work crews who depend on the train dispatcher to provide signal protection, prior to the accident.

It is noticeable that SSDs were a recommendation after a 29 January 1988 accident when a northbound Amtrak train struck engineering equipment in the same town. The NTSB say “Amtrak management failed to issue SSDs to the night foreman, despite their own rules mandating the use of the safety equipment”. Furthermore, NTSB investigators concluded that “there was wide acceptance at Amtrak of not using SSDs” and they were still not a regulatory requirement. The NTSB say the Amtrack procedure for transfer of ‘fouls’ was “cumbersome” and routinely subject to work arounds.

Fourteen safety recommendations were made after the 2016 accident.

In this article we are going to look at some of the safety management, cultural and training lessons, that have relevance beyond the rail industry.

Senior Management Perspectives on Safety

The NTSB say:

Investigators interviewed Amtrak senior executives and division heads… The managers had a variety of attitudes about best safety practices.

Some managers showed little interest or concern about safety beyond the demands of their immediate job responsibilities, others expressed awareness of safety principles but lacked detailed knowledge of them or experience in applying them, and a few managers enthusiastically espoused their use of well-established and contemporary safety management techniques in performing their jobs.

The inconsistent knowledge and views of safety among Amtrak’s managers and executives indicates a significant shortcoming in the company’s safety culture [and] the differing visions of safety within Amtrak have contributed to a failure to establish effective assurances that safety objectives are understood and achieved in a common, progressive manner.

For example:

…the Director of Operating Practices recognized the fallibility of human performance (that is, humans do not perform error free 100 percent of the time) yet failed to acknowledge the inherent risks associated with train dispatchers initiating passenger train movements based solely on verbal communications that tracks are clear.

He would not accept a proposal that train dispatchers…verify [safety-critical information communicated by track foremen] through follow-up questions.

Instead, he strongly relied on old railroad industry adages, such as foremen must follow the rules (report only when tracks are clear), and train dispatchers do not need to slow passenger trains through construction zones because there is no rule that requires it.

Cult of Compliance

Indeed, the NTSB comment that reliance on rule compliance was a common perspective amongst Amtrak managers, evident in multiple interviews, as highlighted in an interview with Amtrak’s Chief Safety Officer:

Question: Do construction zones present any unique challenges from your point of view as chief safety officer?

Answer: Not if you follow the rules. You follow the rules, you follow the procedures out there. The rules, there are rules in place that allow the safe passage of trains. It’s when you don’t follow the rules that you get yourself in trouble. …if you follow the rules and procedures, I don’t see it as much of an issue.

However, some of the procedures in place were “cumbersome”, assumed the use of equipment that wasn’t provided and prone to error.

In an interview with Amtrak’s Director of Operating Practices:

Question: We know rules probably can’t be written to cover every scenario that’s experienced… We know that people can’t be relied upon as 100% rule followers. Is there a take-away from that that may help Amtrak make some improvements beyond what the NTSB recommends?

Answer: I would take exception to your statement that we can’t depend on people to be 100% rule followers. Every employee’s life depends on each and every other employee following the rules. As soon as one employee fails to follow the rules, it puts another employee or the riding public in jeopardy and that’s unacceptable.

We have previously written about a “Culpable Culture of Compliance” after an Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) report in a fatal man over board from the bulk carrier Cape Splendor off Point Headland, WA on 6 October 2014. That report was of interest because it discusses how blindly emphasising compliance without considering risk may also create a culture that actually undermines safety.

The NTSB comment that rules and procedures are of course an essential element of transport operations but they are a a ‘soft’ defence. They quote James Reason in his 1997 Managing the Risks of Organizational Accidents (p8):

Soft defences…rely heavily upon a combination of paper and people: legislation, regulatory surveillance, rules and procedures, training, drills and briefings, administrative controls (for example, permit-to-work systems and shift handovers), licensing, certification, supervisory oversight and—most critically—front-line operators, particularly in highly automated control systems.

Hard defences include such technical devices as automated engineered safety features, physical barriers, alarms and annunciators, interlocks, keys, personal protective equipment, non-destructive testing, designed-in structural weaknesses (for example, fuse pins on aircraft engine pylons) and improved system design.

The NTSB say:

Rules and procedures can provide a layer of protection, but they do not constitute all the layers of protection that would be expected in a safe system. (Reason 1997, p7)

According to Reason ([in Organizational Accidents Revisited] 2016, p 33), “Good procedures should tell people the most efficient and safest way of carrying out a particular task. It should be noted that clumsy procedures are among the main causes of human violations.” [emphasis added]

Safety experts (for example, Reason 1997, p49–51) do not support the notion that a focus on rules compliance can completely assure [technically ‘ensure’] safety.

Despite this, one of the Amtrak actions after the accident was to do more of the same, as they:

Created an independent compliance group outside the engineering department that is composed of a director and four compliance officers augmented by contract support. The group reports to the senior vice president for operations with its initial focus on evaluating compliance with RWP regulations [Roadway Protection Rules – i.e. worker track protection rules] and making recommendations to improve compliance.

One reason for this knee-jerk compliance monitoring reaction is likely to be the volume of safety shortcomings (29 in fact) identified during the investigation:

These…ranged from individual and crew actions to procedural and oversight work practices that facilitated unnecessary risks and increased the likelihood of the accident.

However, the NTSB note (emphasis added):

While mistakes are expected in human work systems, the multitude of unsafe conditions observed indicates a systemic problem. The active failures that occurred indicate that safety was consistently a low priority in the decision making process of the employees involved. The presence of the unsafe latent conditions indicates that management failed to proactively identify and mitigate unsafe conditions.

One reason for that management failure is probably the culture they had created that suppressed learning and open discussion…

Just Culture? Trust or Fear? Learning or Deception?

Union representatives told investigators that…

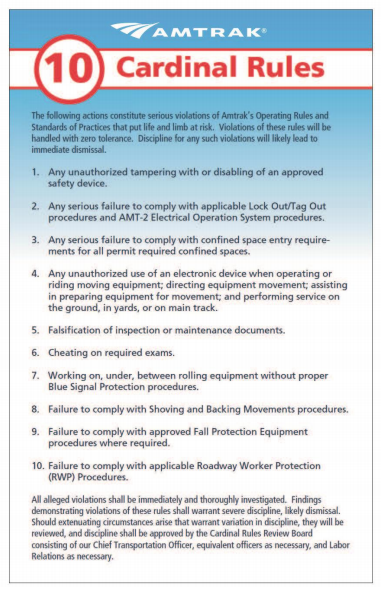

…the work environment was hostile and made it difficult for workers to perform their jobs safely and to provide peer-to-peer protection for their colleagues, because Amtrak had instituted a “Cardinal Rules” program that could lead to workers’ being fired for a single violation.

The NTSB note that:

The rules placed the burden for safety on workers, and did not hold supervisors or managers accountable for safety.

In other words they create ‘a blame layer’ of front-line employees.

One union official recounted he could think of “8 or 10 people…fired for minor violations of RWP” citing as an example:

… one guy was fired because he got out of a truck on a, basically a dead track, where the grass is this high, and [he] didn’t get RWP protection. A train hasn’t been on that track for 25 years. [emphasis added]

Another commented:

…the fear of being fired “sends terror into every man’s thought and family, when you’re without that income….” [and] resulted in vital safety information not being reported. He said that “engineers were reluctant sometimes to report close calls with track gangs, because they didn’t want to involve the track gang in discipline.”

Another claimed Amtrak threatened to fire employees for not following fall protection protocol, but again failed to provide the necessary resources, saying:

There’s no dialogue … it’s fear. I mean you talk to the managers, they’re afraid. And you can talk to the youngest guy. It’s fear.

NTSB Board Member Christopher Hart observed:

If these violations are inherently dangerous, query why management has chosen to go after them with punishment rather than establishing a program to collect information to help:

(a) identify why employees sometimes do things that they know will probably increase the likelihood of injury, and

(b) provide a basis for determining what to do about the problem.

The NTSB say:

It does not appear that Amtrak management considered the negative impact the Cardinal Rules have… [as] the establishment and enforcement of rules can undermine workers’ perception that Amtrak has a just culture, which is “an atmosphere of trust in which people are encouraged, even rewarded, for providing essential safety-related information.” (Reason 1997, p 195)

We have previously been critical of the corrosive misapplication of proprietary Just Culture ‘decision aids’ marketed as bureaucratic tools for managers, who sit above ‘the blame layer’ to routinely ‘judge’…

…individuals not the system, with the potential to inadvertently reduce trust rather than enhance it. The circumstances that influenced an individual’s performance are seen as factors that mitigate culpability rather than systemic opportunities to improve.

Those ‘just culpability’ tools fail to reward feedback, as Reason originally proposed, by anything other than an inquisition upon the individual concerned and even turn investment in coaching and training as a punishment!

Furthermore they are actually even worse than the Amtrak system in that they don’t actually identify in advance any specific unacceptable behaviours that would result in disciplinary action (other than sabotage which is by definition a criminal matter in a safety critical industry). They only help define ‘the line’ between acceptable and unacceptable after the event and are primarily focused on separating front-line employee’s errors from violations. Great for retribution but not very helpful for employees trying to juggle the inevitable complexity of real life.

When articulating the concept of a Just Culture in his classic 1997 book Managing the Risks of Organizational Accidents, James Reason, Professor Emeritus University of Manchester, highlighted (p205) that acts of wilful negligence or misconduct are actually “rare” (one aviation industry association reports such circumstances occur 1 in 500 reported incidents). Consequentially, as we previously wrote:

The destructive misuse of such Just Culture tools, like a modern day ducking stool, has a negative cultural effect, completely the opposite of some misguided advocates, who without realising it are taking a ‘Just Culpability’ approach.

Dr Margaret McCartney wrote in the BMJ after the 2017 Oscars ‘Envelopegate’ announcement fiasco: Punishing individuals won’t prevent errors

By simply punishing the individuals at the end of a trail of errors—as the NHS so often does—we pretend to have fixed the problem. I am no fan of PricewaterhouseCoopers, but the best people to prevent future errors may be the people who nearly—or did—make them. Pretending otherwise: that’s la la land.

Systems ergonomist and human factors specialist Steven Shorrock writes:

So to answer the question, “Just culture: Who do we fear?”: it is the judgement of those close to us – in or from the same world – that we fear the most. It is also those close to us who we can help the most.

The similarity between those proprietary tools and Amtrak approach is that despite the references in the Amtrak cardinal rules to ‘zero tolerance’ and consequently ‘severe discipline, likely dismissal’, Amtrak management actually claimed their process had a spectrum of responses:

Amtrak’s Chief Operations Officer indicated that “every single Cardinal Rule violation goes to a group that looks at the mitigating circumstances, and that group decides what the discipline is going to be, and there’s a progressive discipline process.”

The COO later added that “The perception is, wrongfully so, and I think communication, again, could have been better, that you violate one of these rules, you’re terminated. Nothing could be further from the truth.”

The NTSB establish that in 2016 Amtrak “employees had been terminated in Berlin, Connecticut; Chicago; New York; Denver; Philadelphia; Wilmington, Delaware; and Newark, New Jersey” and the NTSB discuss even considering terminating employees as a form of penalising them (presumably due to the stress, fear and uncertainty). They say:

To address the weak safety culture at Amtrak, senior leadership must stop blaming employees for errors and adopt a system perspective. Senior leadership must address employee fear and engage with workers to correct safety issues. Employees and contractors cannot experience reprisals or negative outcomes for their use of any safety management initiative that incorporates a reporting system intended to collect information on safety vulnerabilities and weaknesses.

In advocating a system perspective, thankfully the NTSB don’t recommend implementing a more formal of assigning ‘accountability’ (or ‘determining culpability’) of front line employees or more ‘compliance monitoring’.

Safety Management System

The NTSB comment that:

For Amtrak to address the safety issues identified in this report, a systemwide overhaul [of their approach to safety management] likely will be required.

They go on to explain how the organisation’s SMS is more than a written document (something we discussed in our 2015 article on accidents at another US railroad whose SMS was just ‘shelfware’: Metro-North: Organisational Accidents).

Amtrak are at the centre of another investigation after an Amtrak passenger service derailed near DuPont, Washington on 18 December 2017 leading to 3 fatalities and an estimated $40mn of damage.

Amtrak Passenger Train 501 Derailment DuPont, WA, 18 December 2017 (Credit Washington State Patrol via NTSB)

Training Inadequacies

The NTSB also observe:

In particular, there appeared to be a gap in Amtrak’s safety training. The Amtrak director of training indicated that there was no field auditing process to evaluate the effectiveness of the classroom training that Amtrak foremen received.

One union official commented that:

…classroom [safety] training was insufficient, and that the instructors lacked experience and could not effectively elaborate on classroom materials. He voiced concern that feedback from the field was not being incorporated into classroom training appropriately.

It is not uncommon to see organisations:

- delivering training rather than facilitating learning

- not assessing the effectiveness of the training they do by anything other than participant feedback forms completed in a rush on the day of the course

New Chief Safety Officer at Amtrak

UPDATE 9 January 2018: Former Flight Safety Foundation Board Chairman Ken Hylander, a retired senior executive with Delta Air Lines, has been named executive vice president and chief safety officer at Amtrak, the passenger rail operator announced. He will report to Amtrak President and CEO Richard Anderson, who previously was CEO at Delta and Northwest who said:

We are improving safety at Amtrak. Keeping our customers and employees safe is our most important responsibility, and a high quality safety management system is a requirement for Amtrak. Ken is a recognized leader in the implementation and operation of SMS, and his experience will be instrumental in helping build our safety culture.

UPDATE 28 January 2018: Amtrak workers warned supervisors before [December 2017 Washington derailment] crash: report

The report cited worries among employees tasked with operating the train, with several sources telling [CNN] that training was “totally inadequate.” …some of the training was conducted at night and involved six or more workers jammed into three-seat cars.

UPDATE 31 January 2018: 1 dead after Amtrak train carrying GOP lawmakers collides with truck in Virginia

UPDATE 4 February 2018: Amtrak Train Crash in South Carolina Kills at Least 2 and Injures 116 in collision with stationary CSX freight train. Note that this appears to be on a CSX operated track.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UPRkSiDs95Q

UPDATE 15 February 2018: The Federal Railroad Administration received one urgent safety recommendation from the NTSB based on its investigation of the 4 February 2018, collision near Cayce, SC. The NTSB say:

…investigators found that on the day before the accident, CSX personnel suspended the traffic control signal system to install updated traffic control system components for the implementation of positive train control. The lack of signals required dispatchers to use track warrants to move trains through the work territory.

In this accident, and a similar accident March 14, 2016, Granger, Wyoming accident, safe movement of the trains, through the signal suspension, depended upon proper switch alignment. That switch alignment relied on error-free manual work, which was not safeguarded by either technology or supervision, creating a single point of failure.

The NTSB concludes additional measures are needed to ensure safe operations during signal suspension and so issued an urgent safety recommendation to the Federal Railroad Administration seeking an emergency order directing restricted speed for trains or locomotives passing through signal suspensions when a switch has been reported relined for a main track.

UPDATE 27 July 2019: The NTSB determined that…

…Amtrak’s and CSX Transportation’s failure to properly assess and mitigate the risk of conducting switching operations during a signal suspension, coupled with a CSX conductor’s error, led to the collision of an Amtrak train with a CSX train near Cayce, South Carolina.

“The train crew omitted throwing the switch that one final time, which unfortunately happens far too often,” said NTSB Chairman Robert L. Sumwalt. “If the same error is repeated by many people, the problem is not the individuals’ performance of their duties, rather, the problem is the failure to mitigate the risk associated with the task they are performing,” said Sumwalt.

View from the UK

In 2017 the UK Rail Accident Investigation Branch (RAIB) issued a report into the safety of track workers working on Network Rail’s infrastructure “outside possessions of the line” (i.e. where normal running of trains continued during engineering work).

Simon French, Chief Inspector of Rail Accidents said:

Our analysis has also found that the behaviour and attitudes of track workers, including those with responsibilities for leading safety, are major factors…

Given that behavioural and cultural issues can lead to breakdowns in site discipline or loss of vigilance, the RAIB considers that the industry should reinvigorate the training it provides to track workers in the ‘non-technical skills’ [NTS] needed to work safely on the railway (i.e. generic skills such as the ability to take information, focus on the task, make effective decisions, and communicate clearly with others).

The report explains that:

Network Rail introduced NTS training following a series of accidents involving track workers, including those at Trafford Park on 26 October 2005 (RAIB report 16/2006), Ruscombe on 29 April 2007 (RAIB report 04/2008) and Stoats Nest on 12 June 2011 (RAIB report 16/2012). This training was originally targeted on COSSs [Controller of Site Safety], although Network Rail declared its intention to expand its scope to include other roles such as lookouts, signallers, electrical control operators and operations control staff. The aim was to see a reduction in incidents that had an underlying cause associated with non-technical skills, and a reduction in the number of accidents and incidents involving COSSs.

NTS training started in 2012.

Five recommendations were made by the RAIB in 2017 to further protect track workers:

- improvements in procedures and/or training for those in leadership roles to be able to adapt to changes in circumstances

- improvements to the training of track workers in non-technical skills

- changes in the competence requirements for people who lead track work in higher- risk situations

- making location-specific photographic and video information more easily available to staff involved in planning and leading work on the track

- improvements in the collection, analysis and reporting of information on incidents involving track workers.

Noticeably they choose not to simply demand better enforcement and compliance monitoring. Their report also acknowledged that sometimes well considered and risk assessed variations away from written rule might be justified in local circumstances that not fit the rule well.

RAIB commented in a another investigation report:

UPDATE 8 February 2018: The UK Rail Safety and Standards Board (RSSB) say: Future safety requires new approaches to people development They say that in the future rail system “there will be more complexity with more interlinked systems working together”:

…the role of many of our staff will change dramatically. The railway system of the future will require different skills from our workforce. There are likely to be fewer roles that require repetitive procedure following and more that require dynamic decision making, collaborating, working with data or providing a personalised service to customers. A seminal white paper on safety in air traffic control acknowledges the increasing difficulty of managing safety with rule compliance as the system complexity grows: ‘The consequences are that predictability is limited during both design and operation, and that it is impossible precisely to prescribe or even describe how work should be done.’

Since human performance cannot be completely prescribed, some degree of variability, flexibility or adaptivity is required for these future systems to work.

They recommend:

- Invest in manager skills to build a trusting relationship at all levels.

- Explore ‘work as done’ with an open mind.

- Shift focus of development activities onto ‘how to make things go right’ not just ‘how to avoid things going wrong’.

- Harness the power of ‘experts’ to help develop newly competent people within the context of normal work.

- Recognise that workers may know more about what it takes for the system to work safety and efficiently than your trainers, and managers.

UPDATE 6 March 2018: RAIB have also published a report on a near miss with staff at Clapham Junction, London, 17 January 2018

Image from the train’s forward facing closed-circuit television camera showing the position of the track workers (with their reflective clothing visible) just prior to the near miss Credit: South Western Railway via RAIB)

UPDATE 9 February 2019: Meeting Your Waterloo: Competence Assessment and Remembering the Lessons of Past Accidents No one was injured in this low speed derailment after signal maintenance errors but investigators expressed concern that the lessons from the fatal triple collision at Clapham in 1988 may have been forgotten.

Other Safety Resources

We highly recommend this case study co-written by our founder, Andy Evans, 2008: ‘Beyond SMS’ by Andy Evans & John Parker, Flight Safety Foundation, AeroSafety World, May 2008 and this 2011 interview with Andy: How Organizational Culture Drives Safety and Quality

You may also be interested in these Aerossurance articles:

- How To Develop Your Organisation’s Safety Culture

- How To Destroy Your Organisation’s Safety Culture a cautionary tale of how poor leadership and communications can undermine safety.

- The US National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) commented on the poor organisational culture and leadership after the loss of de Havilland DHC-3 Otter floatplane, N270PA in a CFIT in Alaska and the loss of 9 lives: All Aboard CFIT: Alaskan Sightseeing Fatal Flight

- Metro-North: Organisational Accidents: the story of shelfware

- Performance Based Regulation and Detecting the Pathogens: which discusses both the Metro-North and the crude oil train derailment and fire that killed 47 people on 6 July 2013 at Lac-Megantic UPDATE 19 January 2018: All 3 MMA rail workers acquitted in Lac-Mégantic disaster trial: Locomotive driver and 2 others found not guilty of criminal negligence causing 47 deaths

- The Power of Safety Leadership: Paul O’Neill, Safety and Alcoa a real life example of safety leadership and how the stock markets reacted badly until O’Neill’s focus on safety, responding to employee suggestions and continuous improvement (not mere compliance) started to created exceptional business performance.

- Chernobyl: 30 Years On – Lessons in Safety Culture

- Leadership and Trust

- Safety Performance Listening and Learning – AEROSPACE March 2017 (co-written)

- Safety Intelligence & Safety Wisdom

Hazards 28 takes place in Edinburgh in May 2018.

UPDATE 26 January 2018: The night the Swiss Cheese holes lined up

After nearly three months of emotional courtroom proceedings and nine days of jury deliberations, three former employees of Ed Burkhart’s now-defunct Montreal, Maine & Atlantic Railway were found not guilty of all charges arising from the 2013 Lac-Mégantic oil train disaster.

One of the best assessments of the Crown’s weak case came from Railroad Workers United (RWU). In its celebratory news release after the not guilty verdict, RWU stated, “While the prosecution focused largely on a single event —the alleged failure of the locomotive engineer to tie enough handbrakes—they were tripped up at every turn by their own witnesses—government, company, ‘expert’ and otherwise—who, by their testimony, incriminated the company and the government regulators rather than the defendants.”

On the night of the disaster, it is likely that if only one of the management decisions had been different, or if only one of the equipment conditions had not been present, the trio of railroaders would have never been in a courtroom.

The mechanical condition of lead locomotive no. 5017 leads to one the event’s many “If Only” situations:

- If only operations manager Dematrie had not dismissed the July 4, 2013 report by engineer Francois Daigle that 5017 was belching black exhaust plumes.

- If only 5017 not been rewired in a way that violated TC safety regulations.

- If only 5017 had not caught fire.

- If only an MM&A employee with air brake system knowledge had been sent to check on the train after 5017’s fire had been extinguished.

MM&A’s “generally reactive” approach to safety, rather than a proactive one, was a major construct of the shoddy safety culture identified by TSB, which also found, “There were significant gaps between the company’s operating instructions and how the work was done day to day.”

The testimony of MM&A’s former safety and training supervisor provided an unflattering portrait of MM&A management. Michael Horan was on the witness stand for six days. During one particularly rigorous cross-examination, Horan told the court he had no formal training in safety education, had no budget, and needed prior authorization to use his company credit card.

MM&A had implemented its SMS in 2002. However, TSB stated TC never audited MM&A’s SMS until 2010, and that other prior inspections showed “clear indications” the SMS was not working properly. One of those clear indications was the discovery by Canadian investigators of another improperly secured MM&A oil train on July 8, 2013, while Lac-Megantic’s downtown was still smoldering.

UPDATE 27 January 2018: Discussion of the terrible misjustice of the Bawa-Garba case where legal and disciplinary action was focused on one NHS doctor, blind to the system problems around her.

UPDATE 5 February 2018: However MMA and a number of workers were convicted on lesser charges: MMA and former employees plead guilty, fined $1.25 million in Lac-Megantic case

UPDATE 12 February 2018: Safety blunders expose lab staff to potentially lethal diseases in UK. Tim Trevan, a former UN weapons inspector who now runs Chrome Biosafety and Biosecurity Consulting in Maryland, said safety breaches are often wrongly explained away as human error.

Blaming it on human error doesn’t help you learn, it doesn’t help you improve. You have to look deeper and ask: ‘what are the environmental or cultural issues that are driving these things?’

There is nearly always something obvious that can be done to improve safety. One way to address issues in the lab is you don’t wait for things to go wrong in a major way: you look at the near-misses. You actively scan your work on a daily or weekly basis for things that didn’t turn out as expected. If you do that, you get a better understanding of how things can go wrong.

Another approach is to ask people who are doing the work what is the most dangerous or difficult thing they do. Or what keeps them up at night. These are always good pointers to where, on a proactive basis, you should be addressing things that could go wrong.

UPDATE 13 February 2018: Considering human factors and developing systems-thinking behaviours to ensure patient safety

Medication errors are too frequently assigned as blame towards a single person. By considering these errors as a system-level failure, healthcare providers can take significant steps towards improving patient safety.

‘Systems thinking’ is a way of better understanding complex workplace issues; exploring relationships between system elements to inform efforts to improve; and realising that ‘cause and effect’ are not necessarily closely related in space or time.

This approach does not come naturally and is neither well-defined nor routinely practised…. When under stress, the human psyche often reduces complex reality to linear cause-and-effect chains.

Harm and safety are the results of complex systems, not single acts.

UPDATE 14 February 2018: Amtrak CEO: How we are making Amtrak safer

Amtrak’s CEO Richard Anderson comments: “we should be careful not to rush to judgement or make broad assumptions about Amtrak’s safety culture”. We don’t have to rush as the NTSB has studied that already. He goes on”Safety compliance has always been a priority for our front line employees; it’s a condition of employment “, the downside of that is exactly a concern that the NTSB identified!

The article does make a sound point that Amtrak is not able to install Positive Train Control (PTC) on all lines because it does not own most of those it operates on but they had at least started where they could in advance of a regulation.

He also is correct that that:

Great things can be achieved when management, employees and stakeholders work together toward a common goal.

UPDATE 16 February 2018: Quebec’s Director of Criminal and Penal Prosecutions will not appeal the not-guilty verdicts reached by the jury on the three rail workers in the Lac-Mégantic accident.

UPDATE 3 April 2018: Lac-Mégantic disaster: No criminal charges will be filed against MMA. It appears difficult to pursue a company under Canadian law if no employee has been convicted, though in this case only front line staff were prosecuted.

UPDATE 7 April 2018: Investigators Criticise Cargo Carrier’s Culture & FAA Regulation After Fatal Somatogravic LOC-I. A Shorts 360 N380MQ, operated by SkyWay Enterprises as a Part 135 flight on contract to FedEx crashed in the Caribbean after the crew likely suffered a Somatogravic Illusion raising the flaps on a dark night in 2014. The lack of an FAA SMS regulation for Part 135, the operator’s poor safety culture and implications for the wider industry culture stand out in a thoughtful accident report.

UPDATE 1 September 2018: Chester’s Amtrak crash leads to new safety protections for rail workers nationwide

…new standards will protect Amtrak workers nationwide, and makes good on some recommendations the National Transportation Safety Board made after the Chester crash, including that labor and management cooperate to make rail work safer.

However, the agreement doesn’t include a key NTSB recommendation following the Chester crash: To give workers and maintenance equipment GPS devices that would automatically alert a train and dispatchers to their presence.

Five maintenance of way workers have been killed by moving trains in the last four years…including the two men killed in the Chester derailment.

UPDATE 9 February 2019: Meeting Your Waterloo: Competence Assessment and Remembering the Lessons of Past Accidents: No one was injured in this low speed derailment in London after signal maintenance errors but investigators expressed concern that the lessons about maintenance errors from the fatal triple collision at Clapham in 1988 may have been forgotten.

UPDATE 14 December 2019: A “culture of safety” is lacking at the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) “according to a scathing report by three outside experts“.

UPDATE 6 June 2020: a study released by the US Federal Railroad Administration’s Office of Research, Development and Technology showed that regular safety culture assessments (in this case by the not-for-profit Short Line Safety Institute against their 10 Core Elements of a Strong Safety Culture) and following up the opportunities identified can improve an organisation’s culture. The study was of only two organisations so a wider study was also recommended. There could also be a halo effect, where assessors treat organisations that respond to their past advice more favourably irrespective of whether the actions were actually effective.

UPDATE 9 August 2025: OceanGate Titan: Toxic Culture & Fatal Hubris

Recent Comments