Metro-North: Organisational Accidents and Shelfware

An NTSB study into five accidents on US railway (‘railroad’) Metro-North gives a unique perspective on organisational accidents. Metro-North was described as having an “invisible safety department”, that kept its SMS on the shelf until external audits and assumed on-time performance would give them safe operations.

Organisational Accidents

James Reason, Professor Emeritus, University of Manchester popularised the expression ‘organisational accident’ in his 1997 book Managing the Risks of Organizational Accidents. He used the term to differentiate simple ‘individual accidents’ involving just one person to complex accidents involving more people, organisations, technology and systems. Reason explained that:

Organizational accidents have multiple causes involving many people operating at different levels of their respective companies.

Such accidents result from ‘latent organisational failures’ that are like pathogens that have infected the organisation. In the earlier, 1995 book, Beyond Aviation Human Factors, Maurino, Reason, et al give examples:

-

Lack of top-level management safety commitment or focus

-

Conflicts between production and safety goals

-

Poor planning, communications, monitoring, control or supervision

-

Organizational deficiencies leading to blurred safety and administrative responsibilities

-

Deficiencies in training

-

Poor maintenance management or control

-

Monitoring failures by regulatory or safety agencies

This case study covers a host of these pathogens. We have also written previously on: James Reason’s 12 Principles of Error Management

The Metro-North Accidents

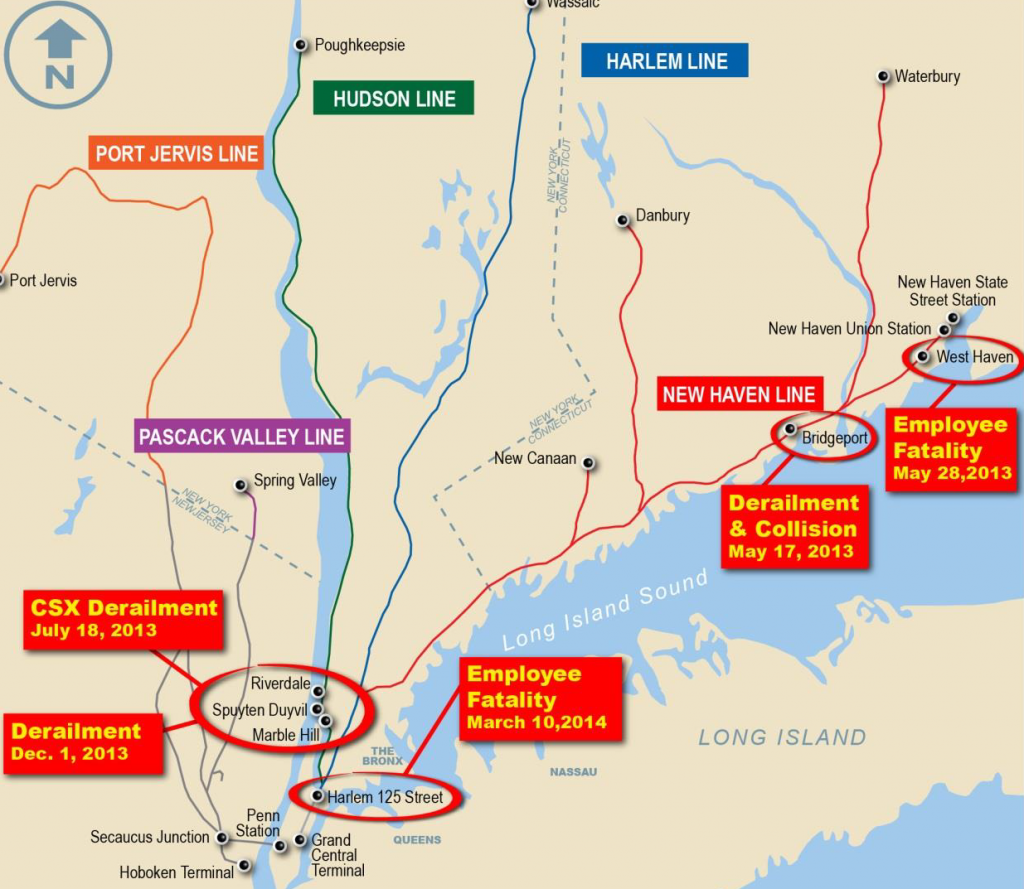

Metro-North is the second largest commuter railroad, and one of the busiest, in the United States. Between May 2013 and March 2014 Metro-North had five significant accidents resulting in 6 fatalities, 126 injuries and more than $28 million in damages.

In November 2014 the US National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) published a special investigation report into the organisational factors that emerged (discussed at a special hearing). This series of accidents is also covered in an excellent DisasterCast podcast by Drew Rae.

Metro-North Safety Management

Although not a regulatory requirement, the New York State Public Transportation Safety Board (PTSB), who conduct ‘safety oversight’ of organisations who receive State transportation grants, requires rail operators to maintain a and update it every 2 years. The American Public Transportation Association (APTA) have issued a manual on the creation of SSPPs. An SSPP is expected from participants in APTA’s voluntary safety management audit program. The NTSB report describes the SSPP as analogous to an SMS Manual in other industries. The Metro-North SSPP stated that it was created to:

…coordinate a safety system for prevention, identification and management of hazards in an effort to minimize safety risks to both customers and employees.

The SSPP also includes the statement that:

Metro-North’s commitment to the SSPP will permeate every aspect of railroad operations.

It is concerning that the commitment is to the plan, rather than to safety (i.e. to the means rather than to the ends). However, far worse the NTSB say:

NTSB investigators found little evidence that Metro-North systematically followed…procedures as described in the SSPP. Moreover, the NTSB investigators found no evidence that Metro-North actually used the SSPP as part of is operational guidance. Aside from senior management personnel, most of the Metro-North employees interviewed by NTSB investigators stated that they had never heard of or seen copies of the SSPP.

Even the organisation’s Chief Safety Officer candidly admitted:

I don’t think it’s effective at all. …my whole 28 years here it was something that we reviewed when APTA and the FRA [the federal regulator the Federal Railroad Administration] came in to do their triennial audit. …it was every few years we’d dust it off, reread it, maybe change a couple of names and department restructuring, some responsibilities a little bit, distribute it, and then it would get maintained just the—well, the appendices would get maintained in our office…

He also explained that the SSPP:

…actually used to just reside out in the hallway there in the file cabinet. It would take up the whole cabinet, all of the appendices in it.

The Metro-North SSPP appears to be classic safety ‘shelfware’. A document created to be primarily read only by outsiders with little influence on safety practices within the organisation.

It wasn’t the only sign of poor documentation. The NTSB note that the organisation’s medical protocols for train drivers had been last revised in 1995, refer extensively to “use of sound clinical judgement” without further guidance and tended to focus on occupational illness rather than human performance. In particular the NTSB note there is no coverage of sleep disorders, an issue contributory to one of the accidents. The SSPP was not the only safety ‘program’ however.

A “core” of the SSPP was Metro-North’s ‘Priority One’ program. This had originally been created by safety consultants DuPont for Metro-North. Aerossurance has recently discussed DuPont’s own safety performance. A Metro-North Board Member tellingly said:

I look back and really the whole safety area was a product of what DuPont made it. And I can’t tell you that there were many changes from the time DuPont’s contract ran out, okay, up until the current time. I mean…everything was running fine. You know, there was no reason to change the policies that were in effect then.

This statement indicates that ‘Priority One’ was a bought-in initiative, with little customisation or user ‘ownership’, that had not been subject to much on-going attention but at least was thought to be working effectively. Unfortunately the NTSB investigation indicates it wasn’t effective:

…most of the employees interviewed were unable to describe the Priority One safety program beyond recognizing it as a slogan that appears on posters and brochures with the railroad’s logo. The program was intended to use structured layers of safety committees to facilitate a shared understanding of safety risks throughout the various layers of the organization and feed unresolved safety concerns upward through the organization for resolution. Meetings were intended as a tool to allow the district safety groups to speak directly with the president about safety actions plans and needs.

Metro-North Safety Reporting, Employee Engagement, Safety Culture and Trust

NTSB interviews revealed operations staff were hesitant to have meaningful discussions on safety and raise concerns. A Metro-North safety officer acknowledged that Priority One meetings presented data without any meaningful review or discussion of safety, commenting that they followed a ‘script’:

These are your numbers, this is what you did, this is how well you did, and these are the good things you’re going to do…they would call it a dog and pony show…there was never a lot of good conversation.

Safety concerns were not being voiced through the Priority One safety help line either:

…records provided to the NTSB indicated that during the 12 months from June 2012 to June 2013, the Metro-North safety helpline only received one call—two first aid kits required restocking.

NTSB note that:

When asked at the NTSB’s investigative hearing what action was taken against the RTC [rail traffic controller] who inadvertently removed the blocking devices in connection with the West Haven fatality, the Metro-North deputy chief of train operations stated he was removed from service and assigned 30 days of discipline, 10 days of which was re-instruction. This type of response to an unintentional mistake could have a chilling effect on employee reporting.

A lack of trust was evident:

…employees interviewed following the employee fatality in Manhattan on March 10, 2014, expressed reluctance to report their safety concerns and exercise their authority to make a good faith challenge for fear of being “blacklisted” or being the target of retaliation from foremen, supervisors, and department heads.

The NTSB report that:

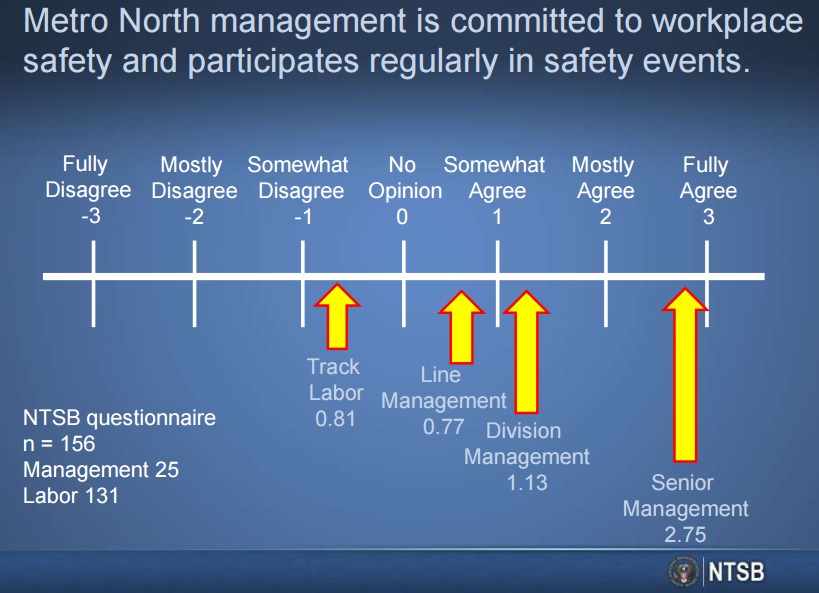

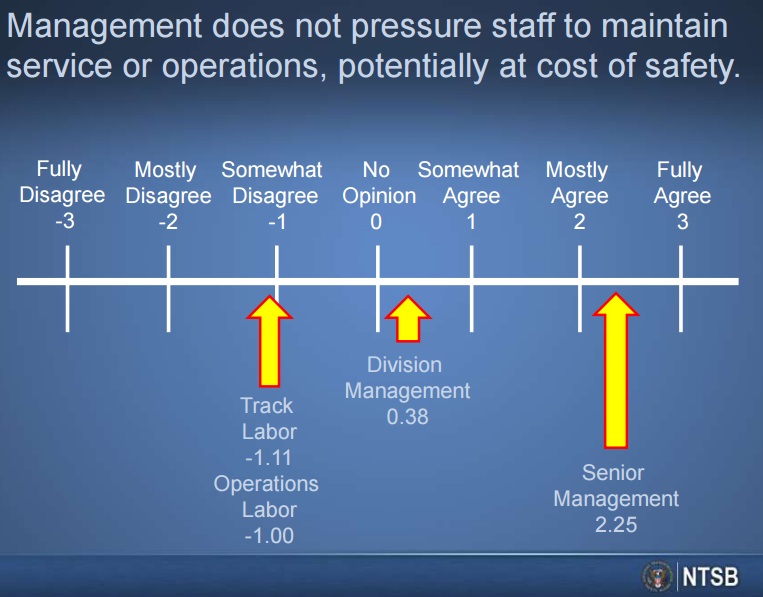

In response to an NTSB survey, most Metro-North management personnel agreed with the statements “Metro-North management is committed to workplace safety and participates regularly in safety events” and “management does not pressure staff to maintain service or operations, potentially at a cost of safety.” However, most of the responding rank-and-file employees disagreed with those statements.

This disconnect is a damning indictment of safety leadership within Metro-North and suggest either a management ignorant or deluded on the state of their organisation. NTSB concluded that Metro-North did not successfully encourage its employees to report safety issues and observations.

Their SSPP/SMS does not seem to have had the capability to detect the early warning signs of impeding failure, as described in Barry Turner’s ground breaking research on Man Made Disasters. Last year we looked at this topic in our article Disasters and Crises – 10 Lessons on Early Warning.

Metro-North’s Real Priority One

The real ‘Priority One’ at Metro-North was not safety but on-time performance, with a flawed assumption that this priority would naturally result in safe operations too. NTSB Board Member Robert Sumwalt commented:

…there seemed to be an obsession at Metro-North with on-time performance—so much so that Metro-North management came to believe that on-time performance could be an effective metric of the health of the system. According to an NTSB interview with Metro-North’s senior vice president of operations, “We were geared towards using the on-time performance numbers as a metric. The philosophy was that if we can deliver trains on time, all of the supporting activity that we did, track maintenance, signal maintenance, and rolling stock maintenance must be performing well if we can deliver that high degree of service reliability.” To use on-time performance as a metric of system health is a flawed assumption, because it overlooks the age-old conflict between production and safety.

Metro-North’s Safety Department and Safety Processes

With the flawed assumption that train operational safety was being monitored by monitoring on-time performance, safety seems to have been seen as an occupational safety issue. Priority One, the core component of the wider SSPP, was focused only on employee safety, not on safe operation of trains and the safety of the travellers who made 83 million journeys on the Metro-North network each year. So for example, other data, such as a trend of track joint bar failures was not being identified because according to the NTSB, Metro-North was “failing to analyze and act on its own data”. One reason was that a lot of track inspection data was still paper based.

Theoretically the Metro-North Safety Department had overall responsibility for implementing and maintaining the SSPP. However, the NTSB found that the Safety Department “was focused on personal injuries and occupational health issues”. Injury rates had decreased but as Australian National University Emeritus Professor Andrew Hopkins has commented in his 2000 book, Lessons from Longford: the Esso Gas Plant Explosion:

Reliance on lost-time injury data in major hazard industries is itself a major hazard.

The NTSB:

…found no indication of the safety department being involved in operational or process safety functions. Testimony…indicated that the safety department was not historically involved in risk assessments for operational decisions.

When changing from a four-track system to a more intensely used two-track system in the Bridgeport derailment area, no formal risk assessment process was used, nor were changes made to the maintenance procedures in response to the increased load.

Internal safety investigations were limited. On 4 May 2013 a train was mistakenly cleared into an area were track workers were working. They escaped injury and the occurrence was reported (though not it seems on the Priority One phone line). However the investigation produced just a 1 page timeline, with no conclusions or recommendations. On 28 May 2013, in similar circumstances, a track foreman was killed.

Even when improvements were made, they inadvertently heightened risk because of inadequate planning. Supervisors were, for example, meant to monitor the performance of Foremen in applying track protection procedures. Having identified that the Foremen were poor at this, it was decided that pending further training only Supervisors would be authorised to control track protection. But no monitoring was then put in place to ensure the Supervisors were effective at it.

When asked about internal audits, the chief of the Safety Department responded: “I don’t think we ever really did (them).” It is no surprise that the department was described by employees as “an invisible department” that “printed brochures”.

Our Conclusions

The NTSB report paints the picture of an organisation with a weak safety culture, that valued on-time performance so highly that it assumed its safety performance must be satisfactory. Safety processes were assumed to be working and in need of little attention, when in fact they were ineffective or missing. The SSPP was ‘shelfware’ cynically updated before external audits by a dysfunctional department that was described as ‘invisible’.

In many ways the NTSB report’s findings on the Metro-North SSPP/SMS is reminiscent of Charles Haddon-Cave QC‘s comments in 2006 on the Nimrod Safety Case during the review into the loss of RAF Nimrod MR2 XV230:

“lamentable job from start to finish”, “fatally undermined by a general malaise”, “virtually worthless as a safety tool”, a “tick box exercise”, “languishing on-the-shelf”, “giving people a false sense of security “, in a “culture of paper safety”.

UPDATE 27 July 2015: This accident also has implications for the evolving concept of Performance Based Regulation (PBR). We discuss these further in a follow up article: Performance Based Regulation and Detecting the Pathogens that also looks at the crude oil train derailment and fire that killed 47 people at Lac-Megantic, Quebec, Canada.

UPDATE 22 September 2015: For a more enlightened view on leadership in railways: Mark Carne – A Leadership Portrait of Network Rail’s CEO

UPDATE 3 May 2016: The US National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) discussed safety culture and a failure to learn at a hearing into an accident at a Board Meeting on a Washington Metrorail (WMATA) smoke and arcing accident that occurred on 15 Jan 2015.

UPDATE 19 September 2016: It’s worth listening to Todd Conklin’s podcast interview with Prof Ed Schein.

UPDATE 22 September 2016: NTSB Board Member Robert L. Sumwalt presented Lessons from the Ashes:

The Critical Role of Safety Leadership to an audience in Houston, TX. Its worth noting the emphasis made of safety as a ‘value’ and of alignment across an organisation. He illustrates that presentation with two charts that show the differences in perception of safety at Metro-North:

UPDATE 6 January 2018: Despite the organisational and regulatory issues at Lac-Megantic identified by the TSB, three workers were tried on 47 counts of criminal negligence causing death.

UPDATE 19 January 2018: All 3 MMA rail workers acquitted in Lac-Mégantic disaster trial: Locomotive driver and 2 others found not guilty of criminal negligence causing 47 deaths

UPDATE 26 January 2018: The night the Swiss Cheese holes lined up

After nearly three months of emotional courtroom proceedings and nine days of jury deliberations, three former employees of Ed Burkhart’s now-defunct Montreal, Maine & Atlantic Railway were found not guilty of all charges arising from the 2013 Lac-Mégantic oil train disaster.

One of the best assessments of the Crown’s weak case came from Railroad Workers United (RWU). In its celebratory news release after the not guilty verdict, RWU stated, “While the prosecution focused largely on a single event —the alleged failure of the locomotive engineer to tie enough handbrakes—they were tripped up at every turn by their own witnesses—government, company, ‘expert’ and otherwise—who, by their testimony, incriminated the company and the government regulators rather than the defendants.”

On the night of the disaster, it is likely that if only one of the management decisions had been different, or if only one of the equipment conditions had not been present, the trio of railroaders would have never been in a courtroom.

The mechanical condition of lead locomotive no. 5017 leads to one the event’s many “If Only” situations:

- If only operations manager Dematrie had not dismissed the July 4, 2013 report by engineer Francois Daigle that 5017 was belching black exhaust plumes.

- If only 5017 not been rewired in a way that violated TC safety regulations.

- If only 5017 had not caught fire.

- If only an MM&A employee with air brake system knowledge had been sent to check on the train after 5017’s fire had been extinguished.

MM&A’s “generally reactive” approach to safety, rather than a proactive one, was a major construct of the shoddy safety culture identified by TSB, which also found, “There were significant gaps between the company’s operating instructions and how the work was done day to day.”

The testimony of MM&A’s former safety and training supervisor provided an unflattering portrait of MM&A management. Michael Horan was on the witness stand for six days. During one particularly rigorous cross-examination, Horan told the court he had no formal training in safety education, had no budget, and needed prior authorization to use his company credit card.

MM&A had implemented its SMS in 2002. However, TSB stated TC never audited MM&A’s SMS until 2010, and that other prior inspections showed “clear indications” the SMS was not working properly. One of those clear indications was the discovery by Canadian investigators of another improperly secured MM&A oil train on July 8, 2013, while Lac-Megantic’s downtown was still smoldering.

UPDATE 8 February 2018: The UK Rail Safety and Standards Board (RSSB) say: Future safety requires new approaches to people development They say that in the future rail system “there will be more complexity with more interlinked systems working together”:

…the role of many of our staff will change dramatically. The railway system of the future will require different skills from our workforce. There are likely to be fewer roles that require repetitive procedure following and more that require dynamic decision making, collaborating, working with data or providing a personalised service to customers. A seminal white paper on safety in air traffic control acknowledges the increasing difficulty of managing safety with rule compliance as the system complexity grows: ‘The consequences are that predictability is limited during both design and operation, and that it is impossible precisely to prescribe or even describe how work should be done.’

Since human performance cannot be completely prescribed, some degree of variability, flexibility or adaptivity is required for these future systems to work.

They recommend:

- Invest in manager skills to build a trusting relationship at all levels.

- Explore ‘work as done’ with an open mind.

- Shift focus of development activities onto ‘how to make things go right’ not just ‘how to avoid things going wrong’.

- Harness the power of ‘experts’ to help develop newly competent people within the context of normal work.

- Recognise that workers may know more about what it takes for the system to work safety and efficiently than your trainers, and managers.

UPDATE 16 February 2018: Quebec’s Director of Criminal and Penal Prosecutions will not appeal the not-guilty verdicts reached by the jury on the three rail workers in the Lac-Mégantic accident.

UPDATE 26 March 2018: We look at another organisation that had SMS shelfware: Indian King Air Take Off Accident: Organisational & Training Weaknesses

UPDATE 9 February 2019: Meeting Your Waterloo: Competence Assessment and Remembering the Lessons of Past Accidents No one was injured in this low speed derailment after signal maintenance errors but investigators expressed concern that the lessons from the fatal triple collision at Clapham in 1988 may have been forgotten.

UPDATE 14 December 2019: A “culture of safety” is lacking at the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) “according to a scathing report by three outside experts“.

Aerossurance has previously looked at other accidents were a weak SMS were a factor including:

- Audits Highlighted Risk Assessment Weaknesses Prior to Ro-Ro Fatality (sea)

- GM Ignition Switch Debacle – Safety Lessons (auto)

- Culture + Non Compliance + Mechanical Failures = DC3 Accident (air)

- UPDATE 6 January 2020: Runway Excursion Exposes Safety Management Issues

- UPDATE 9 August 2025: OceanGate Titan: Toxic Culture & Fatal Hubris

Recent Comments