Safety Intelligence & Safety Wisdom

An EU aviation research project has recently investigated the concepts of organisational safety intelligence (the safety information available) and executive safety wisdom (in using that to make safety decisions) by interviewing 16 senior industry executives.

Virgin Atlantic Boeing 747-400 Taking-off at London Heathrow (Credit: Maarten Visser)

The Future Sky project, initiated by the association of European Research Establishments in Aeronautics (EREA), has been examining the topic of “Resolving the organizational accident” and recently published a paper on Safety Intelligence & Safety Wisdom, which we think is a really useful contribution to the debate on Living Near Zero – New Challenges for Air Safety. They defined these as:

Safety Intelligence the various sources of quantitative information an organisation may use to identify and assess various threats.

Safety Wisdom the judgement and decision-making of those in senior positions who must decide what to do to remain safe, and how they also use quantitative and qualitative information to support those decisions.

The principal authors were Nigel Makins and Barry Kirwan of Eurocontrol. The NLR managed project also included contributors from Airbus, Boeing Research & Technology-Europe, Deep Blue, ENAV, KLM and the LSE. They say:

Both Safety Intelligence and Safety Wisdom are needed. But while Safety Intelligence has been explored to some extent, the way in which top executives make decisions concerning safety is little understood and hardly researched.

Consequently:

Sixteen executives were interviewed from Airlines (3), Airports (3), Air Traffic Management (6), Regulation (2) and Research (2) sectors…

…however not from the manufacturing sector. The interviewees’ responses were organised into five key areas.

1) Safety first – but not at any cost

The interviewees discussed safety as something non-negotiable. However, they note that:

…there are economic and performance pressures on the industry that could soon begin to affect safety – there is less and less ‘fat’ in the system, and the next cost-cutting exercise could impact safety.

2) Maintaining safety under pressure

This is primarily the political and media pressure to act after an accident.

Sometimes a quick reaction is clearly the right one to take, but other times it may be better to wait for more information, or not to react.

3) Accountability and Responsibility at the Top

The senior executives interviewed strongly emphasised their feelings of accountability and responsibility for safety, and this translated into active leadership on safety in their organisations.

One interviewee said:

Taking responsibility for safety is also about demonstrating everyday leadership in building a strong safety culture. Dealing with risks is to lead by example: admit your own errors, do not get angry if people report issues, otherwise they won’t do it next time.

A regulator said:

The debate we’ve been having is where do our responsibilities begin and end. Our job is not only to look after safety from the areas that we have direct control but do our best to improve the overall safety.

It is interesting that they use the term ‘direct control’. The researchers comment:

Regulators in particular need to be clear on their true accountabilities; if they take on too much accountability, this can disempower those they are regulating.

We discuss some of the challenges in: Performance Based Regulation – EASA A-NPA & UK CAA Seminar, Performance Based Regulation and Detecting the Pathogens and Regulatory Reflections & Resisting the Seduction of the Risk Management Process

4) Searching for Evidence

“Many organisations only look at data, but that’s not enough” said one executive. The interviewees said that monitoring quantitative data, such as KPIs, is not enough and emphasised listening to post-holders and frontline staff, to help detect weak signals.

This rich data flow only works if there is a culture of trust in the organisation, and a strong safety culture which ensures that safety information is fed up to the top.

The topic of weak or ambiguous signals was discussed in this 2006 article: Facing Ambiguous Threats. The concept of searching also embraces the idea of mindfulness (discussed by Andrew Hopkins of the the ANU).

We are reminded of Darrell Huff statement in How to Lie With Statistics (1954):

If you torture the data long enough, it will confess to anything.

Data has disadvantages as discussed in the article: Going with the Gut: The Case for Combining Instinct and Data

Data hide[s] biases and obscures the theories underpinning their creation and subsequent analysis. Data are prey to the propensity of their creators and communicators to bend them to their will. Often, data—and the models they feed—rely on the past as a predictor of the future. This is not so useful in an environment of complexity and turbulence.

Although being data-driven sounds like the latest and greatest business imperative, it’s actually high time to bring an appreciation of instinct and intuition back into the lexicon of business.

A recent PwC report Guts and Gigabytes appeared to lament the fact that despite the big advances in data science analytics executives are making many decisions based on instinct. Subsequently the same PwC team reported that, when asked what they will rely on to make their next strategic decision, 33% of executives say “experience and intuition”. This behavior, the authors seem to imply, ought to be eradicated, not celebrated.

Let us be clear. This is not an argument for ditching data. Our gut can be wrong and lead us astray, so we need good data to inform our feel for an issue or situation. But the reverse is also true. We need to recognize, and work with the fact,

Intuition is an area probed by cognitive psychologist Gary Klein in his books Sources of Power and The Power if Intuition. We also recommend this article: Data & Decision-Making: A match made in heaven or….?

5) Seeing around the Corner

The interviewees talked of predicting where the next threats and how that doesn’t come from “collecting data from current situations”:

It is about being able to look forward. Waiting for the regulator to tell you what needs to be done is too late. The past is important, but the focus must be on today and tomorrow.

ATC Tower at Brussels Airport (Credit Wim Bladt)

The Researcher’s Conclusions

The researchers draw out three themes:

Sharing the view of threats within the industry: The interviewees spoke about searching for both quantitative and qualitative safety information.

Keeping the ultra-safe aviation industry safe is being done with richer information sources than a simple target based management approach using just KPI’s. Thus a target based approach only appears to work if it is supplemented by qualitative information such as direct discussions between those operating the organisations and those setting the targets.

Anticipating the next threat: The executives frequently expressed a desire for a “more predictive approach to identifying future threats to safety”.

This has impacts on the way regulators seek evidence to support future regulations. Historical data, especially quantitative data, will not identify future threats. This is about being wise before the event – not waiting for data to accumulate.

Complementing the view from the top: The interviewees had “a strong personal belief that they are doing enough to protect safety in this current economic climate of cost reduction”. In the report, it is stated that management commitment to safety is “the predominate safety climate factor” that “sets the tone for safety in the rest of the organisation” but that this “requires more than simply knowing ‘the safety script'”.

Notably, ‘seeking different perspectives’, is one of the 4 leadership behaviours that a McKinsey study of 189,000 business people concluded collectively accounted for 89% of leadership effectiveness. That needs some empathy:

The researchers recommend looking further at how middle management and front line staff perceive their senior management’s performance.

Our Observations on Safety Intelligence, Wisdom, Quantitative and Qualitative Information, Prediction, Management and Leadership

We think the study’s definition of safety intelligence as purely quantitative data is too narrow and the acquisition of qualitative information should be routine too. We have also previously commented on Safety Data Silo Danger – Data Analytics Opportunity and on the work of sociologist Prof Diane Vaughan, in her book The Challenger Launch Decision (see Challenger Launch Decision – 30 Years On).

However, it is clear the interviewees understood that activities like safety reporting have an improvement focused purpose that goes beyond simply gathering data:

If people feel obliged to participate (in safety reporting) because of the rules, it is OK but not the right way. Teach people so that they feel it is part of their culture[…] Risk is always present, continuous improvement tension has to be part of staff culture.

Rather than just passively “living off” their safety data, the researcher’s note that these top executives reflectively “look beyond the data” with one interviewee commenting:

Don’t rely on the reporting line; speak to the people to gather different views, different priorities and get a global picture to make the decision […] talk to the people on the front line […] If you only rely on the reporting line and figures, that’s not enough!”

As well as seeking out diverse views another commented that once data analysis has identified an issue:

To find out what the cause is – I’ll go and find out because it’s only numbers – I go and say to the base captain, what is going on?

It is encouraging that these executives recognise too that leadership is behavioural not positional and that this means actively engaging with their management team and the workforce, rather than focusing only on KPIs and entries made into a safety database. One interviewee commented on the challenges of safety leadership:

…when you’re talking about the safety leadership, it’s actually how do you communicate? How do you act as a leader on an everyday basis? How do you respond to people’s reactions and things like that? How do you meet complaints…?

Another said:

I think communication is an essential part of safety. Each leader and each boss has to do it. We need to respond much more than we did before. The organization thought that you communicate when you like, but you have to always communicate.”

However sadly, there are safety consultancies that, rather then help with these leadership challenges, are steering executives away from real safety leadership and workforce engagement.

We were recently shown one consultancy’s so called safety leadership brochure by a potential customer. That potential customer was rightly incredulous that safety leadership was described as being indicated by ‘what was discussed in the board room’ (rather than that discussed with the workforce), by the enactment of the organisation’s safety strategy (which we both see as primarily a management output) and ‘by establishing clear accountabilities’ (again a basic management task not true leadership).

Aerossurance has previously discussed what we see as true safety leadership in these articles: How To Develop Your Organisation’s Safety Culture and The Power of Safety Leadership: Paul O’Neill, Safety and Alcoa. We also highly recommend this case study: ‘Beyond SMS’. In Rethinking Leadership “Businesses need a new approach to the practice of leadership — and to leadership development” it is noted that:

We can gain insights into a new model of leadership from the late Nelson Mandela…Mandela frequently emphasized the shared nature of leadership and was known for giving credit to others. For example, when honored for his role in ending apartheid, he would note that abolishing apartheid was a collective endeavor. Perhaps one of the most important leadership lessons we might distill from Mandela was not his acquisition of leadership but the way he shared it.

Mandela’s approach suggests a new way of thinking about leadership — not as a set of traits possessed by particularly gifted individuals, but as a set of practices among those engaged together in realizing their choices. This kind of leadership involves activities such as scanning the environment, mobilizing resources and inviting participation, weaving interactions across existing and new networks and offering feedback and facilitating reflection.

One interviewee discussed making safety improvements “for us, not because we are regulated to”, highlighting that mature organisations don’t just settle for the minima of regulations.

The discussion on Prediction matches the subject of a Royal Aeronautical Society (RAeS) Human Factors Group conference held 26-27 November 2015: Predicting the Fatal Flaws – Can we do things differently in aviation safety?

Aerossurance is aware that, we think bizarrely, the concept of ‘Prediction’ is actually going to be removed from the next revision of the ICAO Safety Management Manual to leave just ‘Reactive’ and ‘Proactive’ approaches. Having three categories is allegedly seen as “too confusing” apparently. We think that’s a retrograde step. For example Human in the System discuss: How to help correct the biases which lead to poor decision making (and Gary Klein’s concept of a pre-mortem discussed in his book The Power of Intuition).

One example of a predictive safety initiative is the work the UK Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) did on the threat of large flocking birds, namely Canada Geese, as it became evident that bird populations were growing and their migratory behaviour was changing.

In a paper authored by Aerossurance’s Andy Evans, then a UK CAA Surveyor, the CAA explained how rule making to enhance engine bird strike resistance was underway but that more needed to be done to manage bird habitats. In particular the paper emphasised the risk of an encounter resulting in loss of power from all engines, saying :

In some areas of North America, the risk of such an encounter may be approaching a critical level.

This was 8 years before A320 N106US lost power from both engines and ditched in the Hudson River.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5SL1A2d2e7M

UPDATE 19 September 2016: It’s worth listening to Todd Conklin’s podcast interview with Prof Ed Schein.

Elsewhere, Malcolm Brinded discussed leadership and how good safety performance and good business performance go hand in hand:

https://youtu.be/kTHtUvgmi78

UPDATE 22 September 2016: NTSB Board Member Robert L. Sumwalt presented Lessons from the Ashes:

The Critical Role of Safety Leadership to an audience in Houston, TX. Its worth noting the emphasis made of safety as a ‘value’ and of alignment across an organisation.

UPDATE 15 October 2016: Suzette Woodward discusses the book Team of Teams, by General Stanley McChrystal, comparing and contrasting intelligence lead special forces operations with managing safety in healthcare (two not obviously similar domains!).

She was struck by a section on intelligence. McChrystal comments: “Like ripe fruit left in the sun intelligence spoils quickly”. Woodward comments:

…think of this in terms of data related to Safety. If an incident reporting system was about fixing things quickly then by the time incident reports reach an analyst most of the information is worthless.

McChrystal goes on:

Too many the intel teams were simply a black box that gobbled up their hard won data and spat out belated and disappointing analyses.

Woodward comments:

We have all heard that one in relation to incident reporting. Our current catch all approach actually creates this problem. Of course with a mass of data every single day anything learnt is going to be belated and disappointing. What this sadly means is that it is often ignored and frankly because of this, time would be better spent doing other things. But that’s a dilemma- we can’t ignore the data but how can all the data be tackled in a timely manner.

McChrystal goes on:

On the intel side, analysts were frustrated by the poor quality of materials and the delays in receiving them and without exposure to the gritty details of raids they had little sense of what the operators needed.

Woodward comments:

This reminded me so much of the way in which we inappropriately compartmentalise safety into neat boxes with people working independently in an interdependent environment. Safety people need to be exposed to day to day experiences and at the same time appreciated and valued for what they bring.

This I would suggest is symptomatic of a larger problem; the way the whole organisation works and dare I say it the overarching system that is there to support them.

It always boils down to people and relationships in the end.

UPDATE 21 November 2016: Safety in mind: Making sense of it all looks at the work of psychologist Karl Weick:

Among Weick’s major ideas is the notion of sensemaking… We create, recall and apply patterns from our life experience to make sense of the world around us and impose some sort of order, or categorise it.

On one hand sensemaking is the individual process used to support situational awareness (SA) and decision making, we also retrospectively use sensemaking intuitively to make better sense of events or experiences that have already happened. In this sense, sensemaking occurs both during and after events.

The sensemaking model provides an alternative to the idea of people and organisations as being rational in their activities and decision-making.

To understand the real-world structure and behaviour of organisations, we need to understand the perceptions, assumptions and values of the people who make up the organisation.

In the sensemaking view, organisations exist more truly in the heads of their members than in bricks and mortar, or rulebooks and constitutions.

One lesson from Weick’s insights for anyone trying to change or improve an organisation, is that others in the organisation will have their own view of it, and their place in it, which may or may not line up with yours. If you want to make sure your changes are understood and acted on, you will have to discover and understand their viewpoints, and you will have to address their concerns.

UPDATE 3 December 2016: How Airlines Decide What Counts as a Near Miss quotes Risk Analysis paper Airline Safety Improvement Through Experience with Near-Misses: A Cautionary Tale. Researchers claim:

…that airlines learn mostly from incidents that conjure the memory of a prior accident. And that could lead pilots and controllers and mechanics to slip into a frame of mind where they routinize close-calls and last-minute adjustments, a natural human tendency toward “the normalization of deviance,” the researchers wrote.

“It’s the ones that don’t scare you that we want the most attention on,” says Robin L. Dillon–Merrill, a professor at Georgetown University and one of the paper’s three co-authors. The researchers write in the study: the “prior near-misses, where risks were taken without negative consequence, deter any search for new routines” and “often reinforce dangerous behavior.”

Shawn Pruchnicki, a former pilot and faculty member at the Ohio State University Center for Aviation Studies said:

“…everyone assumes more data is better, but more isn’t better”. Obsession with data, he says, is part of an obsession with rules, and long prescriptive rules are confining. An aborted takeoff, such as the one in April in Atlanta, may not be the culmination of mistakes, but a symbol of a resilient and flexible system. “It’s all about understanding how the system responds to unfavorable events, how we respond, not the nitty gritty details.”

UPDATE 31 December 2016: A parallel concept to explore is that of organisational agility: Creating Management Processes Built for Change

Good management processes help a company execute its strategy and exercise its capabilities. But in fast-changing business environments, companies also need agile management processes that can help the organization change when needed.

UPDATE 9 January 2017: We discuss High Reliability Organisations (HROs) and Safety Mindfulness, picking up another aspect of the Future Sky research on the shared awareness of emerging threats.

UPDATE 15 January 2017: Power of Prediction: Foresight and Flocking Birds looks further at how a double engine loss due to striking Canada Geese had been predicted 8 years before the US Airways Flight 1549 ditching in the Hudson.

UPDATE 17 January 2017: We discuss new UK CAA guidance: Performance Based Oversight: Accountable Manager Meetings (CAP1508)

UPDATE 24 February 2017: While focused on company boards this article is relevant for all management teams: Intelligent Boards Know Their Limits

Today, the real challenge for decision makers is how to turn knowledge into insight. Board members are overloaded with information and are attempting to make the right decision in a short period of time. For the decision process to be effective, board members need to understand how their brains work.

Among all the biases affecting quality of judgement and decision making at board level, the most common one is certainly the overconfidence effect.

Playing the devil’s advocate and framing the problem through different angles will reduce the effect of the cognitive distortions that lead groups astray.

It is now recognised that the practice of referring to “the expert on the board” is very risky…[as this]…presents the perfect setting for a wrong decision if boards do not seek “intelligence” by inquiring further and testing the so-called experts. It is now recognised that the practice of referring to “the expert on the board” is very risky.

Expertise, diversity and inquiry are key practices that make a board intelligent. The members of such a board collectively reflect on how they make judgements and decisions, and practice “score keeping” – developing an understanding of how often and why they have been wrong in the past. In this way board members become aware of their own biases and become more effective in addressing them. These boards also embrace diversity and feedback as essential practices for developing their intelligence.

UPDATE 1 March 2017: Safety Performance Listening and Learning – AEROSPACE March 2017

Organisations need to be confident that they are hearing all the safety concerns and observations of their workforce. They also need the assurance that their safety decisions are being actioned. The RAeS Human Factors Group: Engineering (HFG:E) set out to find out a way to check if organisations are truly listening and learning.

The result was a self-reflective approach to find ways to stimulate improvement.

UPDATE 15 March 2017: The first Future Sky Safety public workshop was held on the 8-9 March, 2017 in Brussels, at Eurocontrol Headquarters.

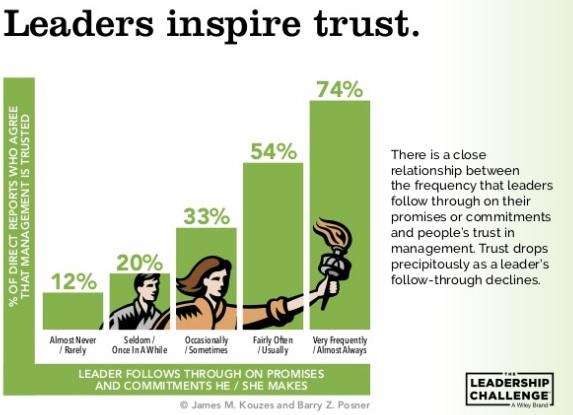

UPDATE 22 March 2017: Which difference do you want to make through leadership? (a presentation based on the work of Jim Kouzes and Barry Posner). Note slide 6 in particular:

UPDATE 25 March 2017: In a commentary on the NHS annual staff survey, trust is emphasised again:

Developing a culture where quality and improvement are central to an organisation’s strategy requires high levels of trust, and trust that issues can be raised and dealt with as an opportunity for improvement. There is no doubt that without this learning culture, with trust as a central behaviour, errors and incidents will only increase.

UPDATE 12 April 2017: See our article: Leadership and Trust

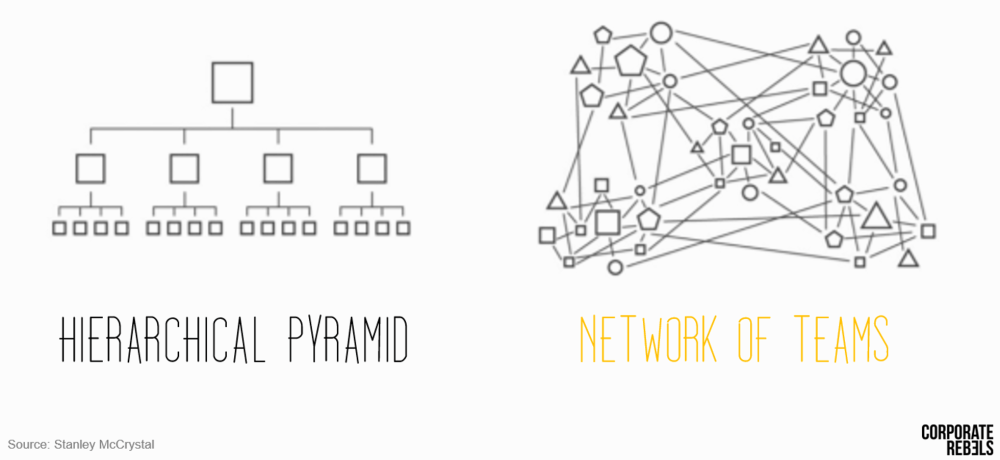

UPDATE 14 May 2017: Destroy the hierarchical pyramid and build a powerful network of teams say the Corporate Rebels:

Out of the eight trends we see, this one is the most disruptive to an organization. But because of that, it might also be the one that has the most impact on the engagement of employees and the success of an organization.

In reality, our organizations are simply not a collection of clearly distinguishable departments and roles as shown in [atraditional organisation chart]. Therefore, we should stop designing them like this. No wonder that most of the progressive organizations we’ve visited moved away from this traditional organizational structure.

Many of the progressive organizations we visit welcome a so-called “Network of Teams”.

For this to happen, we should begin to tear down our familiar organizational structures so we can start rebuilding them along more fluid lines. We need to dissolve the barriers that once made organizations efficient but are now slowing them down.

Then let us design structures that actually work and aim to distribute authority and autonomy to individuals and teams. …establish[ing] flexible structures that allow individuals to gather as members of multiple teams within multiple contexts.

They say the key learnings to start the journey are:

- Create small, multidisciplinary teams and split them when they grow over 15 members;

- Have each team craft its own purpose within the organizational purpose;

- Make teams responsible for their own results and give them a (financial) stake in the outcome;

- Create transparency to foster a healthy dose of competition;

- Leverage the power of technology to create alignment.

UPDATE 19 May 2017: Representatives from 33 European air navigation service providers and the EUROCONTROL met in Frankfurt, Germany on 11 May 2017 for the biennial EUROCONTROL CEOs’ Safety Conference. In his keynote opening address, Joe Sultana, Director Network Manager, posed some questions to stimulate discussion on how ANSPs can maintain and improve their safety record:

- Understanding safety performance is difficult; what data do we really need to understand safety?

- Often ‘work as done’ differs from ‘work as imagined’;

- It’s hard to see things that change slowly over time; people adapt, adjust and make trade-offs;

- Anticipating the future is getting harder; how can we look around the corner to see what is coming?

- Simply tightening safety regulation won’t work on its own. Constraints are necessary but “work as done” shows the need for a degree of flexibility. So, how do we find the right balance with regulation and flexibility so as to build safe, resilient systems?

UPDATE 8 February 2018: The UK Rail Safety and Standards Board (RSSB) say: Future safety requires new approaches to people development They say that in the future rail system “there will be more complexity with more interlinked systems working together”:

…the role of many of our staff will change dramatically. The railway system of the future will require different skills from our workforce. There are likely to be fewer roles that require repetitive procedure following and more that require dynamic decision making, collaborating, working with data or providing a personalised service to customers. A seminal white paper on safety in air traffic control acknowledges the increasing difficulty of managing safety with rule compliance as the system complexity grows: ‘The consequences are that predictability is limited during both design and operation, and that it is impossible precisely to prescribe or even describe how work should be done.’

Since human performance cannot be completely prescribed, some degree of variability, flexibility or adaptivity is required for these future systems to work.

They recommend:

- Invest in manager skills to build a trusting relationship at all levels.

- Explore ‘work as done’ with an open mind.

- Shift focus of development activities onto ‘how to make things go right’ not just ‘how to avoid things going wrong’.

- Harness the power of ‘experts’ to help develop newly competent people within the context of normal work.

- Recognise that workers may know more about what it takes for the system to work safety and efficiently than your trainers, and managers.

UPDATE 30 April 2018: The Best Leaders Are Constant Learners: “…leaders must scan the world for signals of change, and be able to react instantaneously. …leaders bear a responsibility to renew their perspective in order to secure the relevance of their organizations.”

UPDATE 28 July 2018: Performance-based regulations have changed oversight responsibilities: When it comes to regulating the aviation industry, focusing on an organisation’s performance can pay large safety dividends, says Stephanie Shaw, the UK CAA’s Head of PBR.

UPDATE 17 September 2018: How Self-Reflection Can Help Leaders Stay Motivated. This HBR article does fall into the trap of treating leadership as a noun, i.e. position related, rather than a verb, i.e a behaviour, but otherwise some good thoughts of reflection.

UPDATE 6 January 2020: Runway Excursion Exposes Safety Management Issues

UPDATE 2 May 2020: Why Taiwan was the only nation that responded correctly to coronavirus

Our brains are hardwired to expect the future to be much like the past. Like the rest of us, people in charge of complex institutions tend to cling to assumptions of normalcy. Psychologist Daniel Kahneman calls this tendency the “positive optimistic bias.”

Taiwan seems to have followed the model recommended by disaster expert [Diane] Vaughan [see Challenger Launch Decision]: It doesn’t expect infallibility from its leaders. Instead, Taiwan makes sure that its health institutions are hyper-vigilant about epidemic risks.

It’s understandable to want to hold public officials accountable for a disaster like COVID-19. But we shouldn’t assume that putting new people in charge of the same flawed institutions will fix the problem. Instead of imagining a perfect world where ideal leaders make no mistakes, we should study how stronger institutions can keep us safer next time.

UPDATE 28 October 2020: An Uncoordinated Fall from an A320 at Helsinki: How Just Reporting is Not Enough

Recent Comments