Aboard CFIT: Alaskan Sightseeing Fatal Flight and Safety Culture (Promech Air DHC-3 Otter N270PA)

A Controlled Flight Into Terrain (CFIT) accident in Alaska provides a case study of a pathological safety culture, with management and peer pressure, compounded by poorly thought out contracting and scheduling by a cruise line which meant aircraft were making high risk flights in poor weather.

Wreckage of Promech Air de Havilland Canada DHC-3T Vazar Turbine Otter N270PA near Ketchikan (Credit: NTSB)

The Accident Flight

A turbine powered de Havilland DHC-3 Otter floatplane, N270PA, operated by Promech Air, impacted mountainous terrain in the Misty Fjords National Monument near Ketchikan, Alaska at around 12:15 Local Time on 25 June 2015. All 9 persons on board died. The flight was an on-demand sightseeing flight that had departed at about 12:07 from Rudyerd Bay and was en route back to the operator’s base at the Ketchikan Harbor Seaplane Base.

The 8 passengers were from the Holland America Line cruise ship Westerdam were returning for a so called ‘all onboard time’ of 12:30 (prior to a 13:00 sailing). The flight was sold as a “Cruise/Fly” shore excursion for the cruise ship passengers.

In their investigation report US National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) explain that N270PA:

…was the third of four Promech-operated float-equipped airplanes that departed at approximate 5-minute intervals from a floating dock in Rudyerd Bay.

The accident flight and the two Promech flights that departed before it were carrying cruise-ship passengers who had a 1230 “all aboard” time…. The fourth flight had no passengers but was repositioning to Ketchikan for a tour scheduled at 1230; the accident pilot also had his next tour scheduled for 1230.

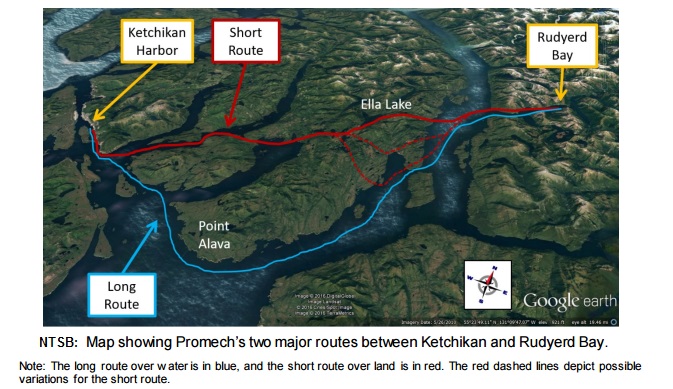

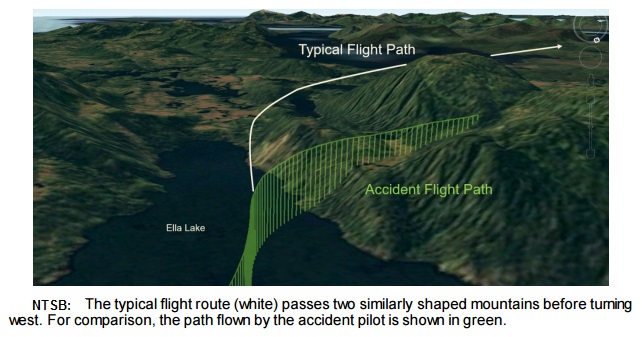

Promech pilots could choose between the ‘short route’ (about 52 nm, taking typically 25 minutes, primarily over land) and the ‘long route’ (about 63 nm, taking about 30 minutes, primarily over water). The latter is less scenic, but was preferred in poor weather as it allowed safe flight below a low cloud base and offered the ability to perform a precautionary water landing if needed.

The pilot of the second Promech flight chose the long, over water, route and the other three the short, overland, route. The Promech General Operations Manual required both the pilot and the flight scheduler jointly agree beforehand that a flight could be conducted safely, this did not occur before the accident flight. Information from multiple sources:

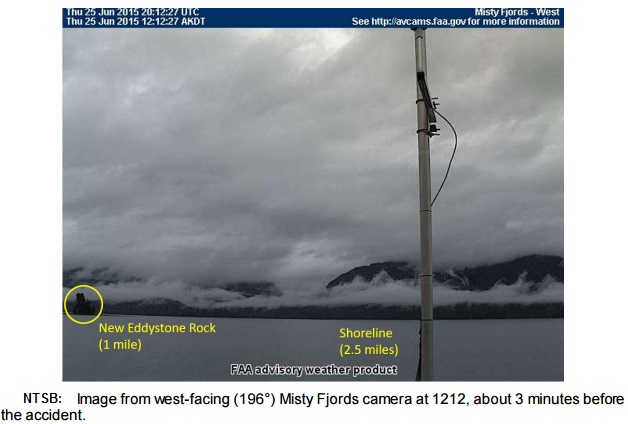

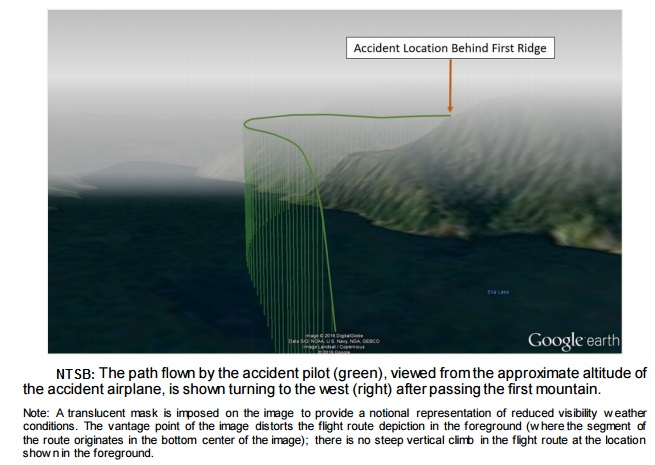

…provided evidence that the accident flight encountered deteriorating weather conditions. Further, at the time of the accident, the terrain at the accident site was likely obscured by overcast clouds with visibility restricted in rain and mist.

Although the accident pilot had climbed the airplane to an altitude that would have provided safe terrain clearance had he followed the typical short route (which required the flight to pass two nearly identical mountains before turning west)…

…the pilot instead deviated from that route and turned the airplane west early (after it passed only the first of the two mountains).

Several factors were present during the accident flight that increased the likelihood that the pilot would make a navigational error. Visibility was degraded over the south end of Ella Lake; thus, the pilot may not have been able to clearly distinguish some of the landmarks by which he typically navigated. In addition, the accident pilot was flying the route at a relatively low altitude because of the poor weather conditions, which resulted in his viewing terrain from a lower-than-normal vantage point.

Contrast sensitivity declines with age, beginning about age 40 (the pilot’s age was 64); therefore, the accident pilot may have had less ability to identify features in reduced contrast visual scenes like those obscured by rain or mist.

The pilot’s relative unfamiliarity with the landmarks on the tour route and the area weather dynamics may have affected his ability to accurately assess and respond to the deteriorating weather conditions he encountered

The pilot’s route deviation placed the airplane on a collision course with a 1,900-ft mountain, which it struck at an elevation of about 1,600 ft mean sea level.

The NTSB Survival Factors Specialist’s Factual Report considered survivability issues. The cause of death for all individuals was determined by the Coroner as “multiple injuries.”

Promech Air

The NTSB say:

At the time of the accident, Promech employed about 30 to 40 people, which included 3 full-time and 9 seasonal pilots. The company operated nine airplanes (four DHC-3 and five DHC-2 airplanes) in Ketchikan and two DHC-3 airplanes in Key West, Florida, where it had a satellite tour operation. The company president/CEO, the DO, assistant chief pilot, and director of maintenance were located in Ketchikan, and the chief pilot was located in Key West. In addition to their management roles, the company president/CEO, the DO, and the assistant chief pilot also had flying duties.

The company had no specific safety officer position; the DO was responsible for safety management,

Regarding a flight risk assessment process, the DO said that, although he had worked with formal risk assessment forms in other jobs, he believed that Promech was able to accomplish the same objective informally.

In their General Operations Manual the company had a:

Safety Report Form by which employees could report observed safety hazards or safety concerns, including suggested corrective action, and a section in which the receiving supervisor could note the investigation of the issues and the corrective action taken.

The examples of its use mainly related to occupational safety matters:

When asked specifically about nonpunitive safety reporting for the pilots, the DO said that pilots could submit a form anonymously using the collection box, which he would check from time to time, but there was never anything in it. The DO said that he believed that everyone knew that they could bring up anything they wanted and that he liked to think that Promech’s culture was one in which pilots felt free to bring up issues that were bothering them.

The DO worryinly described the company’s safety culture almost as an alternative to implementing an SMS.

Airmanship and Organisational Culture

The NTSB say the accident pilot “had less than 2 months’ experience flying air tours in South East Alaska and had demonstrated difficulty calibrating his own risk tolerance for conducting tour flights in weather that was marginal”. Two other pilots reported witnessing the accident pilot flying into deteriorating weather previously. One radio call asking, “how’s the weather up there because it looks IFR here?”. He told the NTSB that:

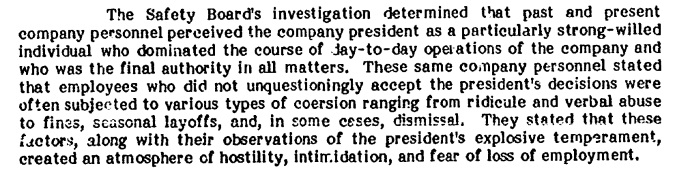

…company management had heard the radio exchange and ridiculed him for mentioning IFR on the radio. He said that he was told to never say “IFR” on the radio, or he would be fired.

They both also described:

…an occasion in which they warned the accident pilot via the radio about an area of severe downdrafts that they had encountered in Rudyerd Bay. They said that the accident pilot disregarded their warning and instead heeded the advice of his friend (another Promech pilot) who said that the conditions were fine.

…when the accident pilot attempted to fly through the area, he encountered a downdraft, and the floats of his airplane struck trees. An entry in the accident pilot’s logbook, dated June 14, 2015, included a note, “Misty Trip, Thought I was dead.” [Investigators determined that this logbook entry was referring to that downdraft flight].

The company management stated that they were not aware of any issues regarding that flight. No safety report was filed through the company’s anonymous reporting system.

While the company’s more experienced pilots told the NTSB that they did not feel pressured to fly in unsafe conditions one of these pilots was part of the group that encountered the 200-ft ceiling during the second tour of the day. This pilot also told investigators that he “had never needed to turn down a flight for safety-related reasons”. Conversely during that second tour of the morning of the accident:

…some of the Promech airplanes passed a DHC-2 operated by Taquan Air’s DO who was performing a weather check. The Taquan DO said that, as a result of this flight, he determined that the weather conditions between Ketchikan and Point Alava were not adequate for Taquan to operate tours because the flights could not maintain the required minimums in that area.

However Taquan, the company that eventually purchased Promech in 2016, were an exception:

According to ADS-B data, at least four other operators were flying tours during this period.

The NTSB go on:

One less-experienced pilot (who had about 500 hours flying float-equipped airplanes and had worked for Promech for about 6 weeks at the time of the accident) described that, when he arrived for work on the morning of the accident, he expressed concern to Promech’s president/CEO that the weather conditions were not good enough to fly. He stated that the response he received was, “That’s just Alaska weather,” so he flew the tour.

This pilot also reported that he overheard the company president/CEO expressing frustration in the company office when he saw (using the company’s ADS-B display) that one of the pilots was returning from the accident tour via the long route.

He also stated that, during initial training, the assistant chief pilot, when talking about weather minimums, told him and a group of other Promech pilots that they had to bend the rules because they were operating in Alaska.

He said that the assistant chief pilot also said that, if one pilot turned around while the others made it through, he and that pilot were going to “have a conversation.”

This pilot, who had not previously flown commercially in Alaska before working for Promech, said he just assumed “that’s the culture [in Alaska]… it’s like, ‘we push through, we push through.’”

In contrast:

The DO provided an example of having praised the accident pilot on one occasion when he was the only pilot in one particular group of flights to abort a tour and return to base because he felt the weather conditions were unsafe; one of the other pilots who had flown in that group said that the other pilots also reacted positively to the accident pilot’s decision.

Although this superficially suggests a safety-oriented organizational culture, there is no indication that Promech questioned the appropriateness of the other pilots’ decisions to continue their tours in the same weather conditions. As a result, it is likely the pilot’s decision to return to base in adverse weather conditions was actually negatively reinforced because the actions of the other pilots indicated that it was acceptable to continue.

The NTSB go on to say:

Considered together, these multiple accounts of pilots, including company managers, suggest the normalization of flying in weather conditions below FAA minimums. The NTSB concludes that, as evidenced by the company president/CEO’s own tour flights on the day of the accident, Promech management fostered a company culture that tacitly endorsed operating in weather conditions that were below FAA minimums.

Social psychological research indicates that people may look to others for cues on how to behave in uncertain situations, a phenomenon called “social proof”; social proof has been documented in a variety of contexts, including aviation, where it has been shown that the decisions of other pilots flying directly ahead significantly influences the behavior of those who follow (Facci, Bell, and Nayeem 2005; Rhoda and Pawlak 1999).

The risky behavior exhibited by other Promech pilots and management may have increased the difficulty that the accident pilot had in evaluating the risks associated with adverse weather, particularly considering that he had relatively little experience flying in the Ketchikan area. Research has identified that difficulty evaluating risks is an important factor in weather-related accidents (Johnson and Wiegmann 2015).

The accident pilot’s more conservative decision-making when flying alone versus his continued flights into adverse weather when following other Promech flights (including those piloted by company managers and another experienced pilot he admired) provides evidence that the accident pilot struggled with calibrating his own perceptions of risk in Promech’s risk-tolerant organizational culture before the accident

Thus the NTSB concluded that the pilot’s decisions were influenced by:

- Schedule pressure

- His attempt to emulate the behaviour of other, more experienced pilots

- Promech’s organizational culture, which tacitly endorsed flying in hazardous weather conditions

“Lives depended on the pilot’s decision making,” said NTSB Acting Chairman Robert Sumwalt at a pubic hearing on the accident.

Pilot decisions are informed, for better or worse, by their company’s culture. This company allowed competitive pressure to overwhelm the common-sense needs of passenger safety in its operations. That’s the climate in which the accident pilot worked.

Comments on Culture and Safety

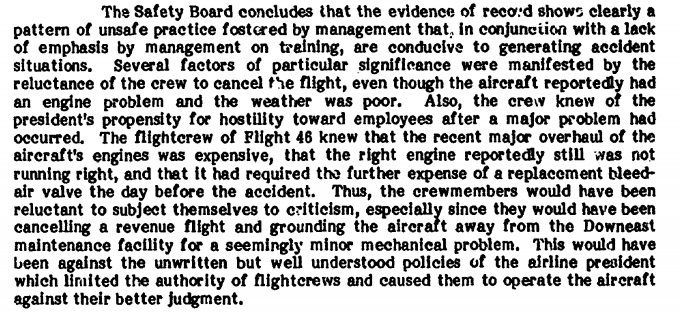

While the NTSB don’t use the term, they imply Promech had a pathological safety culture (Prof Patrick Hudson proposed the following model, developed from earlier work by Ron Westrum):

When discussing this model, Hudson wittily explains why brown was chosen as the colour for the pathological to whom bad things just happen…

Some of the management behaviour described by the NTSB is reminiscent of that in the Downeast Airlines N68DE DHC-6-200 Twin Otter accident on 30 May 1979 in which 17 people died. The NTSB report stated:

From NTSB report AAR-80-05 on Downeast Airlines, Inc., DeHavilland DHC-6-200, N68DE, Rockland, Maine, May 30, 1979

Aerossurance has previously written about operators with cultural problems:

- Culture + Non Compliance + Mechanical Failures = DC3 Accident

- ‘Competitive Behaviour’ and a Fire-Fighting Aircraft Stall

The Cruise Line: Holland America Line / Carnival Corporation

The cruise line marketed air tours to its passengers online and on board the ship for a commission.

…one benefit of purchasing a shore excursion through the cruise line (rather than from the air tour operators directly) is that cruise ship guests incur no expenses if a late-returning excursion delays the ship’s departure (or causes the guests to miss its departure).

…if a ship sailed without guests who were delayed due to a late arriving tour, the tour operator would be responsible for the accommodations and travel expenses associated with delivering those passengers to the ship’s next port of call. …it was very rare for a tour to be late and cause guests to miss the “all aboard.”

The shore excursion manager for the ship stated the decision to fly or cancel a tour remains exclusively with the air tour operator. For the day of the accident, the cruise line sold tours operated by both Promech and Taquan. After Taquan decided to cancel its tours due to concerns about the weather, the cruise line rebooked the Taquan passengers onto Promech flights.

The shore excursion manager stated that, about 1200 on the day of the accident, she was on the dock working to receive the returning tours, which involved communicating with the ship…regarding tour arrival times; she said that, in Ketchikan, there is a “big push” to get everyone on board because the ship has to be at its next port on time. She said that, at 1220, a representative of the bus company responsible for bringing guests from the Promech base back to the ship informed her that an airplane was late.

In interviews with Holland America Line and Carnival Corporation personnel it was stated that the process for air tour operator addition was broadly as follows:

- Tour operator requests a user account for the Carnival Corporation web based Tour Operator Gateway

- Tour operator accepts Tour Operator Policies and Procedures

- Tour operator submits insurance information and proposal

- Once approved, tour operator places bid on upcoming season

- Information review

- Pricing for tour determined

- Tour description created to sell to passengers

Approval did not require an on-site visit or audit and most discussion was over insurance assessment. No aviation expertise appears to have been utilised in the review.

Promech had been an existing tour operator with HAL for “a very long time” but use was suspended after the accident.

The cruise line did activate their family assistance process after the accident.

The cruise industry has extensive experience with risk assessment practices and SMS in its shipboard operations; however, the NTSB is concerned that the industry may not be aware that the cruise line’s schedule may contribute to the schedule pressures air tour operators face associated with returning shore excursion passengers to their ship on time.

The NTSB do not comment on the cruise line’s safety culture.

NTSB Safety Issues

The NTSB identified ten safety issues. We discuss these below in more detail.

Safety Issue 1): HF / ADM Training

Need for training program improvements for Ketchikan air tour operators that address pilot human factors issues such as pilot assessment of safe weather conditions, pilot recognition of potentially hazardous local weather patterns, and operational influences on pilot decision-making.

Safety Issue 2): ADS-B Data Analysis

Need for collaboration among Ketchikan air tour operators to identify and mitigate operational hazards through analysis of automatic dependent surveillance-broadcast (ADS-B) data.

The NTSB comment they were able to “gain valuable insight” analysis recorded ADS-B data and that the industry should also do routine reviews (a sort of poor-mans Flight Data Monitoring) saying:

The FAA could facilitate such a data review and discussion at the annual beginning-of-season or end-of-season Ketchikan Air Safety meeting it conducts with Ketchikan air tour operators. To ensure open discussion and sharing of information about hazards experienced by meeting participants, this discussion should be nonpunitive for the individual participants and aimed at examining the effectiveness of existing risk controls and identifying ways in which safety could be improved.

Apart from Alaska, the other area where there is widespread ADS-B coverage in the US is the Gulf of Mexico. A similar approach could be taken to provide greater insight into the operation of aircraft not subject to FDM.

Safety Issue 3): Weather Minima

Lack of conservative weather minimums for Ketchikan air tour operators.

The NTSB observe that the Ketchikan air tour industry is “competitive” and “operators that were willing to take the most weather risks were able to fly more revenue passengers”, a behaviour they predict is likely to continue. The NTSB say:

Ketchikan’s air tour industry, which involves the operation of float-equipped airplanes at low altitudes through fjords and mountain valleys, is different from other major air tour hubs in Alaska, such as Denali National Park (which involves mostly mountain flying) and the Juneau Ice Field (which involves primarily helicopter operations).

More conservative minimums, particularly when combined with open discussions of how actual behavior compares with the established requirements (for example, through a review and discussion of ADS-B data as described above), can help establish a safety-oriented culture that will encourage pilots to fly more conservatively

Safety Issue 4): CFIT-Avoidance Training

Lack of defined curriculum segments for CFIT-avoidance training for all 14 CFR Part 135 operators.

Such training is not required for fixed-wing pilots under Part 135, only for helicopter pilots. While the accident pilot had undergone CFIT training on a DHC-3 with a view limiting device, the NTSB report he “had trouble correctly completing the inadvertent IMC/CFIT-escape maneuver and had to make multiple attempts to complete the maneuver successfully”.

Safety Issue 5): TAWS Nuisance Alerts

Nuisance alerts from the Class B terrain awareness and warning system (TAWS) during tour operations.

The Otter was required to be equipped with Class B TAWS by 14 CFR 135.154(b)(2). Its Chelton Flight Systems FlightLogic electronic flight instrument system (EFIS), provided free under the Capstone Project, could provide voice alerts and visual caption when approaching terrain. The NTSB note that N270PA was…

…authorized, per 14 CFR 135.203(a)(1), to cruise over the surface as low as 500 ft agl, which is below the Class B TAWS [700 ft] alerting threshold. Several tour pilots reported that frequent nuisance alerts during tour operations prompted them to inhibit the alerts.

The TAWS on N270PA was found inhibited.

Nuisance alerts and the associated increase in the use of the inhibit mode prevent TAWS from effectively providing the intended protection.

Safety Issue 6): TAWS Databases

Limitations of older software and terrain database versions for the legacy Chelton Flight Systems FlightLogic EFIS.

The system’s original 2003 terrain database, which was the version installed “does not distinguish small, inland bodies of water from the surrounding terrain”. The 2007 terrain database “depicts bodies of water in blue’. Some aircraft also had earlier software versions where symbology “may not be as transparent and may obscure the terrain depiction on the map”. The NTSB point out that “older software and terrain database versions can negatively affect the usefulness of these systems for reference”. They make no comment on any requirement for operators to update TAWS software and databases or the infrequent software updates from the manufacturer.

Aerossurance has discussed issues with TAWS and TAWS databases previously in:

- EASA Decisions on Management of Aeronautical Databases / Part-DAT

- Extreme Latitudes – Extra CFIT Risk

- HTAWS Technology: Friend or Foe?

- CFIT Gangnam Style – Korean S-76C++ and Decision Making

Safety Issue 7): Operational Control Training

Lack of minimum training requirements for operational control personnel and lack of guidance for FAA inspectors for performing oversight of operational control training programs.

The NTSB concluded that Promech’s training and supervision of the flight scheduler was “insufficient”.

The flight scheduler who was on duty at the time of the accident held a private pilot certificate and had worked at Promech for 5 years. She stated that this was her third summer working as flight scheduler and that her training for her duties consisted of studying the GOM and operations specifications and receiving on-the-job training. She could not recall how long her initial training lasted, and she had not received any recurrent training.

Additionally, the FAA has no minimum training requirements for such personnel and provides no guidance for their inspectors on expected training.

Safety Issue 8): Cruise Industry Awareness of Schedule Pressure

Need for cruise industry awareness of schedule pressures associated with air tours sold as shore excursions.

The NTSB go on to say, rather generously that the “cruise industry may not be aware that air tour operators that fly air tours as cruise line shore excursions may face schedule pressures to return passengers to the ship on time”. In practice, the shifting of financial penalties for late returns to the tour operators is an obvious incentive to accept flights in deteriorating weather and press on, especially when cancelled tours are rebooked with other air tour operators (rewarding them for accepting a higher risk).

Aerossurance has recently written about a case where schedule pressure from an oil and gas customer contributed to a serious incident with an offshore helicopter: Strictly Scheduled: S-92A Start-Up Incident

Safety Issue 9): SMS Requirements

Lack of a requirement for a safety management system (SMS) for Part 135 operators.

Promech lacked an SMS, but it was not required to have one by regulation. 14 CFR Part 5, as we have previously discussed, is only required for 14 CFR Part 121 carriers.

The NTSB concludes that an SMS can benefit all Part 135 operators because they require the operators to incorporate formal system safety methods into their internal oversight programs.

The NTSB previously observed the lack of an SMS requirement in Part 135 after HS 125-700A (Hawker 700A) N237WR suffered a LOC-I on approach at Akron, Ohio. The then NTSB Chairman Christopher Hart commented on the importance of an SMS being: “an effective set of practices, not a binder full of disregarded procedures that sits unused on a shelf” and Aerossurance has previously written about the danger of SMS Shelfware.

Safety Issue 10): FDR Requirements

Lack of a crash-resistant flight recorder system.

Data retrieved from the EFIS, passenger PEDs, as well as recorded ADS-B data assisted the NTSB investigation. This size of aircraft is not required to have an FDR fitted. Aerossurance has previously written about this topic: EASA Launch Rule Making Team on In-flight Recording for Light Aircraft

The NTSB Probable Causes

(1) the pilot’s decision to continue visual flight into an area of instrument meteorological conditions, which resulted in his geographic disorientation and controlled flight into terrain; and

(2) Promech’s company culture, which tacitly endorsed flying in hazardous weather and failed to manage the risks associated with the competitive pressures affecting Ketchikan-area air tour operators; its lack of a formal safety program; and its inadequate operational control of flight releases.

NTSB Safety Recommendations

As a result of the investigation the NTSB issued nine recommendations to the Federal Aviation Administration and one to the Cruise Lines International Association. The NTSB also reiterated three previously issued recommendations to the FAA.

Background to Ketchikan Air Tour Operations

Video footage of a tour on N270PA in 2010:

https://youtu.be/HJRd_inBOlI

UPDATE 19 June 2017: A DHC-2 from Ketchikan crashed and sank yesterday on take off from a lake in the national park. The 7 POB (inc 6 cruise passengers) were uninjured but had to swim for shore.

UPDATE 13 May 2019: Two floatplanes (DHC-3 Otter N959PA and DHC-2 Beaver N952DB) with eleven and five occupants onboard were involved in a mid-air collision about 8nm from Ketchikan, Alaska while conducting Misty Fjords scenic tours. The Otter was from Taquan Air and carrying Royal Princess cruise ship passengers. The Beaver was being operated by Mountain Air Service.

Other Resources

Aerossurance has previously written about safety culture including:

- How To Develop Your Organisation’s Safety Culture

- How To Destroy Your Organisation’s Safety Culture

- The Power of Safety Leadership: Paul O’Neill, Safety and Alcoa

Also:

- Gulfstream G-IV Take Off Accident & Human Factors

- Fatal G-IV Runway Excursion Accident in France – Lessons

- Wait to Weight & Balance – Lessons from a Loss of Control

- Fatal Night-time UK AW139 Accident Highlights Business Aviation Safety Lessons

- CFIT Gangnam Style – Korean S-76C++ and Decision Making

- Catastrophe in the Congo – The Company That Lost its Board of Directors

- LOC-I Departure: AAIB Report on King Air 200 Accident

- Unstabilised CL-600 Approach Accident at Aspen

- UPDATE 25 June 2017: During an air ambulance positioning flight in Iceland an Impromptu Flypast Leads to Disaster, begging more questions on organisational culture.

- UPDATE 11 August 2017: Deadly Combination of Misloading and a Somatogravic Illusion: Alaskan Otter A night departure of a Otter in Alaska into a ‘back hole’ when outside of the weight and CG limits resulted in spatial disorientation, a stall and LOC-I.

- UPDATE 29 October 2017: How a Cultural Norm Lead to a Fatal C208B Icing Accident

- UPDATE 7 November 2017: Running on Fumes: Fatal Canadian Helicopter Accident

- UPDATE 23 February 2018: NTSB Reveal Lax Maintenance Standards in Honolulu Air Tour Helicopter Accident

- UPDATE 7 April 2018: Investigators Criticise Cargo Carrier’s Culture & FAA Regulation After Fatal Somatogravic LOC-I. A Shorts 360 N380MQ, operated by SkyWay Enterprises as a Part 135 flight on contract to FedEx crashed in the Caribbean after the crew likely suffered a Somatogravic Illusion raising the flaps on a dark night in 2014. The lack of an FAA SMS regulation for Part 135, the operator’s poor safety culture and implications for the wider industry culture stand out in a thoughtful accident report.

- UPDATE 10 April 2018: The NTSB has issued five new recommendations to the FAA and reiterated eight previously issued recommendations, based upon their investigation of an 2 October 2016 Hageland Aviation Services Cessna 208B Caravan N208SD that impacted mountainous terrain near Togiak, Alaska, killing all 3 on board during a Part 135 flight. Among the reiterated recommendations: “Need for safety management systems (SMS) for Part 135 operators. Hageland did not have an SMS at the time of the accident but was working toward implementation”. The NTSB also note that “…this investigation found gaps in Hageland’s CRM training and the FAA’s oversight of that training.”The NTSB say:

As a result of its investigation the NTSB again called for fixed-wing Part 135 pilots – aviators who operate commuter and on-demand aircraft – to receive the same controlled-flight-into-terrain, or CFIT, avoidance training oversight as their rotary-wing counterparts. Currently, only Part 135 helicopter operators are required to train their pilots using an FAA-approved CFIT avoidance training program. While Hageland offered CFIT training based on guidance from the non-profit Medallion Foundation, the investigation found the training was outdated and did not address specific CFIT risks Hageland pilots face while flying under visual flight rules near Alaska’s mountainous terrain

The investigation also found that while Hageland aircraft were equipped with a terrain avoidance warning system, or TAWS, Hageland pilots routinely turned off the aural and visual alerts while flying at altitudes below the TAWS alerting threshold to avoid receiving nuisance alerts, preventing the system from providing the intended protections.

The full accident report will not be available for several weeks but the executive summary, including the findings, probable cause and safety recommendations, is available.

- UPDATE 9 July 2018: In a safety investigation report released last week, the TSB said that the operator of a survey Piper PA-31 Navajo C-FQQB, was unaware that the accident pilots “had frequently flown at very low altitudes” while transiting between survey areas and their base. The Navajo was flying between 40 ft and 100 ft AGL when it struck power cables on 30 April 2017. TSB reiterated a call for flight recorders on smaller aircraft.

- UPDATE 8 September 2018: Torched Tennessee Tour Trip (B206L N16760) An ungreased fuel pump spline failed, the aircraft crashed and suffered a fatal post crash fire.

- UPDATE 13 October 2018: Low Viz Helicopter Accident, Alaska

- UPDATE 17 November 2018: Investigation into F-22A Take Off Accident Highlights a Cultural Issue

- UPDATE 12 May 2019: Alaskan Mid Air Collision at Non-Tower Controlled Airfield

- UPDATE 16 May 2019: Survey Aircraft Fatal Accident: Fatigue, Fuel Mismanagement and Prior Concerns

- UPDATE 20 May 2019: Regulatory oversight of New Zealand helicopter operators was challenged after a 2015 accident.

- UPDATE 20 November 2019: Unalaska Saab 2000 Fatal Runway Excursion: PenAir N686PA 17 Oct 2019

- UPDATE 31 December 2019: Costa Rican C208B Stalled While Trying To Avoid High Ground

- UPDATE 19 May 2020: Survival Flight Fatal Accident: Air Ambulance Operator’s Poor Safety Culture

- UPDATE 13 September 2020: Hawaiian Air Tour EC130T2 Hard Landing after Power Loss (Part 1)

- UPDATE 18 October 2020: Hawaiian Air Tour EC130T2 Hard Landing after Power Loss (Part 2 – Survivability)

- UPDATE 17 January 2021: Grand Canyon Air Tour Tragic Tailwind Landing Accident

- UPDATE 25 April 2021: A Second from Disaster: RNoAF C-130J Near CFIT

- UPDATE 4 August 2022: DC3-TP67 CFIT: Result-Oriented Subculture & SMS Shelfware

Recent Comments