‘Competitive Behaviour’ and a Fire-Fighting Aircraft Stall

The Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) has released its report into the accident on 14 August 2014 in which a fire-fighting Air Tractor AT 802A Fire Boss Amphibian C-GXNX, operated by Conair, stalled on takeoff and crashed into Chantslar Lake, British Columbia. The accident highlighted what TSB called “competitive behaviour” that resulted in eroding safety margins.

The pilot received minor injuries and the aircraft was substantially damaged.

The Accident Flight

The aircraft, operating as Tanker 685, was carrying out wildfire management operations. It was in a group of four single-engine air tankers (SEATs) coordinated by a Cessna 208 Caravan ‘Bird Dog’.

On one of Tanker 685’s scooping runs [as second aircraft], control was lost during liftoff, and the aircraft’s right wing struck the water.

The floats then struck the water and separated from the fuselage as the aircraft yawed 270 degrees to the right. The aircraft remained upright and slowly sank.

The pilot exited the cockpit and inflated the personal flotation device being worn. The fourth aircraft jettisoned its load, rejected its takeoff, and taxied to pick up the pilot who had been slightly injured.

The aircraft’s Emergency Locator Transmitter (ELT) was activated by the impact, but the aircraft sank before a COSPAS-SARSAT satellite picked up the signal (a “common occurrence” say the TSB).

The Safety Investigation

The TSB found that:

…a wing stalled, either independently or in combination with an encounter with a wing-tip vortex generated by the lead aircraft. This caused a loss of control moments after liftoff and resulted in both the right-hand wing tip contacting the water and a subsequent water-loop.

The takeoff procedure used, with the aircraft being heavy, its speed below the published power-off stall speed and a high angle-of-attack, contributed to loss of control at an altitude insufficient to permit a recovery.

The pilot’s takeoff procedure complied with company procedures, but the procedure contained elements of risk which exposed the pilot and the aircraft to the hazard of a power-on stall….

It is possible that pre-stall buffets due to handling errors, which were common for years, were misdiagnosed and mistakenly attributed to other causes such as wake turbulence, mechanical turbulence, or wind gusts. If the aircraft is operated outside of the demonstrated flight envelope, there is a risk that pilots will be exposed to aircraft performance for which they are not prepared.

Additionally, during the wreckage examination two potential control interference hazards were identified (though neither influenced the accident):

One was exposed rudder control cables on the floor that ran along both sides of the pilot’s seat. These cables may be subject to interference by items placed on top of them.

The other was the exposed elevator control push-pull tube, which is attached to the control stick about 4 or 5 inches above the floor under the pilot’s seat and runs parallel to the longitudinal axis of the airplane. The push-pull tube may be subject to interference by loose objects on the floor becoming lodged on its left side and preventing full left roll control input.

Organisational Factors and SMS

While the TSB could have stopped here they also examined organisational matters in depth.

Conair is a well respected specialist aerial firefighting company that:

…employs about 250 people (including 80 pilots) and has a fleet of 65 fixed-wing aircraft. For the 2014 fire season, the Air Tractor fleet consisted of 14 AT-802A Fire Boss aircraft (on amphibious floats) and 11 AT-802A aircraft on wheels.

TSB note that in Canada:

…firefighting operations are carried out under CARs Part VII, Subpart 2 (aerial work). Operators under this subpart are not required to implement an SMS, but this operator did so voluntarily…

Conair’s safety management program was initiated in 1996. The company hired a full-time safety manager and concentrated on developing a culture of openness in an effort to improve the safety of flight operations. In 2008, the safety manager retired and Conair recruited a new manager of safety to continue development of the company’s SMS.

Despite years of effort, employee buy-in and safety reporting required continuous encouragement. These processes were more firmly established in the Abbotsford, British Columbia, hangar maintenance operation, likely because most aircraft maintenance engineers (AME) worked all year in the same environment, whereas the pilot community worked on seasonal contracts.

Conair management was actively working on developing and sustaining its safety culture through all of its SMS processes and activities; safety of operations was a constant agenda item in senior executive meetings.

Since an SMS was not required, the company’s SMS was not subject to TC oversight or inspections… A comprehensive external (insurance related) SMS audit (covering occupational health and safety, and the rest of operations) was completed in 2014 with a very favourable audit of the company’s processes.

The TSB go on to say:

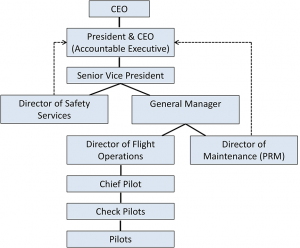

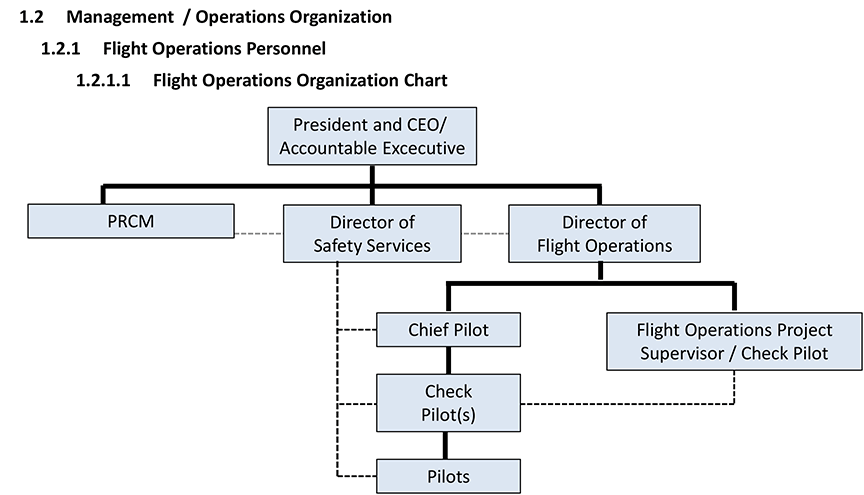

The company experienced significant organizational changes between 2010 and 2014. Its organization chart for 2010 identified 5 management levels, occupied by 5 people, above the company check pilot position, plus the director of safety services (DSS).

At that time, there were 3 check pilots supporting the chief pilot (CP).

During the 2011 and 2012 periods, Conair divested itself of another business entity, and a re-organization of the company management structure resulted in the removal of 2 levels of upper management. The director of flight operations (DFO) was also temporarily replaced, and the 3 company check pilot positions became vacant.

Two risk assessments were conducted…in 2012. The risk assessments identified the hazard that important safety elements might be dropped due to increased workload. Temporary mitigations were implemented to redistribute priorities and responsibilities among other senior managers, but an effective solution had to be implemented before training started in the spring of 2013.

In 2013, the director of safety services became the new DFO and continued to cover the vacated DSS position, with assistance from the quality assurance manager, until a suitable replacement could be found.

In 2014, company organization charts identified 3 management levels above the company check pilot position.

Efforts to hire a new DSS continued and were successful in January 2014; however, this position was suddenly vacated again when the individual left the company in July 2014.

The operator had first acquired two wheeled AT-802 in 1996 for evaluation. The TSB claim that in the late 1990s:

As operational experience was gained with the Fire Boss, the pilots learned the capabilities of the aircraft through occurrences of exceeding limitations and SOPs (flying overweight, experimenting with flap settings, takeoffs below the published stall speed, etc.) [and] pilots began competing with each other and refined an unorthodox procedure to “horse it off”: a manoeuvre that takes advantage of the aircraft’s capability to pitch up and lift off at lower indicated airspeed and shorter distances.

The effort to compete with other aircraft types and operators and meet client requests created an environment where exceedances of the aircraft’s limitations occurred.

By 2013, efforts by management to encourage compliance with company procedures, safety policies, and safety culture led management to believe that the Fire Boss bases and operations [only in Alberta at that time] were operating in accordance with company expectations and that their efforts were achieving success.

In 2014, the company began a multi-year contract with the government of British Columbia… The British Columbia Fire Boss base was operated with some new and some returning contract pilots. The geographical region served by this group was mountainous, with narrow lakes at higher elevations confined by high terrain, making group scooping operations more challenging.

Although this operation was new, it was viewed by management as an extension of the Alberta operation, and no additional hazard identification or risk analysis process was deemed to be necessary. An operational safety survey of the British Columbia base was conducted by the manager of quality assurance in May 2014; no risk findings were made.

However:

Following an inter-base exchange of 2 pilots, personnel issues at the British Columbia base were raised informally. Trying to exceed the client’s expectations may have unwittingly contributed to the competitive manner in which the aircraft was flown by some individuals. Efforts by the director of flight operations (DFO) and chief pilot (CP) to address these issues began with base visits [about 5 weeks before the accident].

Without sufficient management supervision, both the lack of specified takeoff speed in the SOP and the client influence may have contributed to the manner in which the aircraft was flown by some individuals.

The investigation also found that, even though a safety management system (SMS) and processes were in place, an understaffed management structure during organizational changes likely led to excessive workload for existing managers, and contributed to risks not being addressed through the operator’s SMS. Safety management and oversight is an issue on the TSB Watchlist.

Safety Actions

TSB report that:

After the occurrence and before the 2015 spring training season started, Conair hired a safety manager and a company check pilot for the Fire Boss fleet. Conair also put forward a risk mitigation plan for 2015-16 for the company’s AT-802 fleet, which addressed issues found during the investigation.

A Latitude Technology IONode ‘Onboard Loads Monitoring System‘ was due to be installed on each Fire Boss for the 2016 fire season. This Flight Data Monitoring (FDM) system:

…will record preset parameters which can include aircraft pitch angle at takeoff, flap setting, airspeed, ground speed and more to enhance operational oversight so that unsafe techniques such as forcing the aircraft to lift off at unsafe airspeeds can be eliminated.

The TSB also report that:

Conair is endeavouring to enhance its hazard identification and risk assessment efforts to ensure all hazards associated with the Fire Boss operation are identified, assessed and mitigated. Ground school material and operational procedures are being reviewed and will be modified before the 2016 season to ensure that pilots are trained to mitigate all hazards of the operations.

Our Comments

The TSB makes several comments about safety reporting. However, in practice, especially when certain behaviour is considered ‘normal’, its not realistic to rely on safety reporting.

In this case, the inadequate depth of risk assessments before commencing operations and the difficultly of objective monitoring flying standards of a seasonal pilot population in a fleet of single engined aircraft during operations without FDM and with an understrength management team are more significant opportunities for improvement.

Interestingly though, while the TSB do mention culture in relation to the operator’s approach to safety they stop short of suggesting their was a cultural problem in the British Columbia fire-fighting unit. In contrast the US Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board (the CSB) claimed a flawed safety culture at the Williams Olefins ethylene and propylene plant in Geismar, Louisiana, after a fatal explosion and fire, after what we would consider SMS failings without any in-depth cultural consideration.

The end result of this ‘competitive behaviour’ has some similarity with that due to the phenomena of procedural drift / practical drift. One major study of an accident that featured drift was by Scott Snook, then of the US Army. His book, Friendly Fire, examined the accident shoot down of two US Army Black Hawk helicopters on a peacekeeping mission in Iraq in 1994 by the US Air Force, and what he called ‘practical drift’.

Such drift occurs when group norms and practices start to deviate from formal procedures. In some cases this may be because procedures no longer match operational circumstances, however practicality can be a factor too. These do not appear to have been factors here. Instead, the practice seems simply to have been a misguided ‘improvement’.

In The Field Guide to Understanding Human Error Prof Sidney Dekker lists several potential reasons for procedural drift:

- Rules or procedures are over-designed and do not match up with the way work is really done.

- There are conflicting priorities which make it confusing about which procedure is most important.

- Past success (in deviating from the norm) is taken as a guarantee for safety. It becomes self-reinforcing.

- Departures from the routine become routine. Violations become compliant behaviour with local norms.

Although not discussed in detail by the TSB, this is another accident that highlights that customers for aviation services need to be careful not to create undue commercial pressures, even inadvertently, that erode safety margins.

Other Resources

Aerossurance has previously written the following:

- Procedural Drift at Saab 340 Operator Leads to Taxiway Excursion

- ‘Procedural Drift’: Lynx CFIT in Afghanistan

- HEMS Black Hole Accident: “Organisational, Regulatory and Oversight Deficiencies”

- Gulfstream G-IV Take Off Accident & Human Factors

- Fatal G-IV Runway Excursion Accident in France – Lessons

- Culture + Non Compliance + Mechanical Failures = DC3 Accident

- Execuflight Hawker 700 N237WR Akron Accident: Casual Compliance

- How To Develop Your Organisation’s Safety Culture

- Chernobyl: 30 Years On – Lessons in Safety Culture

- 10 Year Anniversary: Loss of RAF Nimrod MR2 XV230

- USMC CH-53E Readiness Crisis and Mid Air Collision Catastrophe

- UPDATE 17 November 2018: Investigation into F-22A Take Off Accident Highlights a Cultural Issue

- UPDATE 1 December 2018: Helicopter Tail Rotor Strike from Firefighting Bucket

- UPDATE 1 September 2019: King Air 100 Stalls on Take Off After Exposed to 14 Minutes of Snowfall: No De-Icing Applied

- UPDATE 4 October 2020: Investigators Suggest Cultural Indifference to Checklist Use a Factor in TAROM ATR42 Runway Excursion

- UPDATE 9 January 2021: Korean Kamov Ka-32T Fire-Fighting Water Impact and Underwater Egress Fatal Accident

- UPDATE 7 August 2022: DC3-TP67 CFIT: Result-Oriented Subculture & SMS Shelfware

We have previously discussed leadership here: The Power of Safety Leadership and in this pre-Haddon-Cave case study: ‘Beyond SMS’ by Andy Evans (our founder) & John Parker, published by the Flight Safety Foundation in May 2008.

UPDATE 31 May 2017: The US National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) commented on the poor organisational culture and leadership after the loss of de Havilland DHC-3 Otter floatplane, N270PA in a CFIT in Alaska and the loss of 9 lives: All Aboard CFIT: Alaskan Sightseeing Fatal Flight

UPDATE 9 July 2018: In a safety investigation report released last week, the TSB said that the operator of a survey Piper PA-31 Navajo C-FQQB, was unaware that the accident pilots “had frequently flown at very low altitudes” while transiting between survey areas and their base. The Navajo was flying between 40 ft and 100 ft AGL when it struck power cables on 30 April 2017. TSB reiterated a call for flight recorders on smaller aircraft.

Aerossurance has extensive air safety, operations, organisational culture & safety leadership development and safety analysis experience. For practical aviation advice you can trust, contact us at: enquiries@aerossurance.com

Follow us on LinkedIn and on Twitter @Aerossurance for our latest updates.

Recent Comments