Investigation into F-22A Take Off Accident Highlights a Cultural Issue: 07-4146 at NAS Fallon, 13 April 2018

On 15 November 2018 the US Air Force (USAF) released the Accident Investigation Board (AIB) report into a Lockheed Martin F-22A Raptor 07-4146 accident at NAS Fallon, NV on 13 April 2018.

The Accident Flight

The F-22A of the 90th Fighter Squadron, based at Elmendorf-Richardson, Alaska, was taking off from Fallon for a Top Gun graduation exercise, operating against US Navy F-18s. The aircraft was rotated at 120 knots calibrated airspeed (KCAS) and the pilot subsequently raised the landing gear handle (LGH) to retract the landing gear (LG) on sensing the aircraft becoming airborne. However, just after the main landing gear (MLG) retracted, the aircraft settled back on the runway. The MLG doors were shut but the nose landing gear (NLG) doors were still in transit.

The aircraft slid over 6,500 ft (1985m), stopping 9,400 ft (2,865m) from the runway threshold. The pilot was uninjured.

Early reports of an engine malfunction, possibly based on engine nozzle positions, proved false (the nozzles free float in an in-flight shut down and in this case when weight on wheels was not activated).

The Investigation

The investigators make much of the fact that Takeoff and Landing Data (TOLD) was not calculated for the conditions that day at NAS Fallon as required. Consequently, the TOLD on the pilot’s lineup card was based on a…

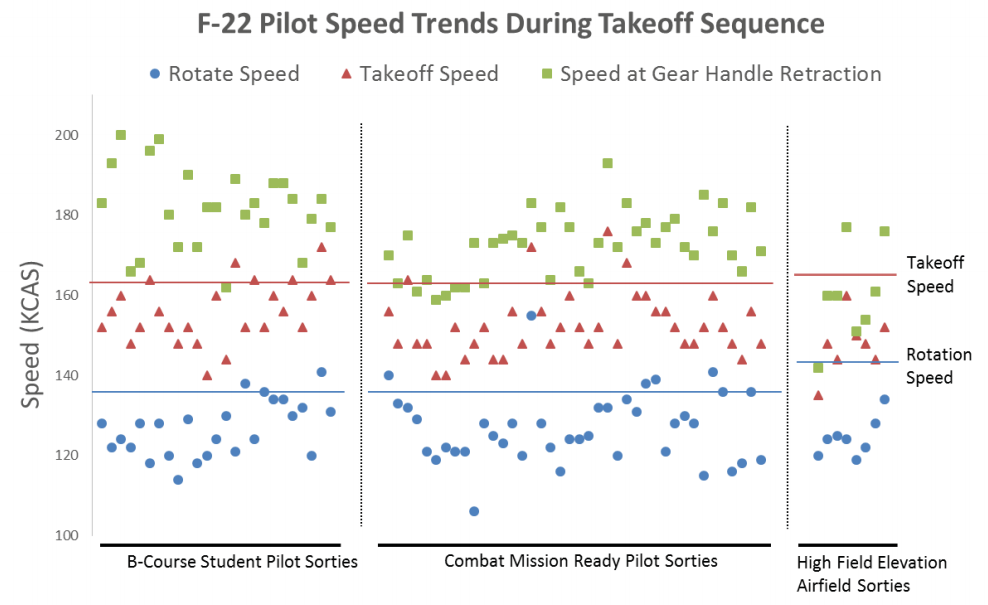

…a military power (MIL) takeoff at 80 degrees Fahrenheit (F) using a 10,000 ft runway at sea level. The elevation of NAS Fallon is 3,934 ft, runway 31L is 13,961 ft long, and the temperature on the morning of the mishap was 46 degrees F. The rotation and takeoff speeds listed on the lineup card were 136 KCAS and 163 KCAS respectively. The calculated rotation and takeoff speeds for the conditions at NAS Fallon on the day of the mishap are 143 KCAS and 164 KCAS respectively.

The pilot based his decision on whether the aircraft was airborne on peripheral vision only. without verifying the climb dive marker (CDM) was above the horizon or the vertical velocity indicator (VVI) was positive. In fact, the pilot had initiated rotation at just 120 KCAS. This was 16 knots below the line up card and 23 knots below a correctly calculated rotation speed. Weight off wheels occurred at at 135 KCAS. This was 28 knots below the line up card and 29 knots below a correctly calculated take off speed. The F-22A momentarily became airborne, but there was insufficient lift to sustain flight. Data from five past sorties showed that this pilot initiated rotation at 120±5 KCAS. The pliot stated:

There is a technique that I heard from somewhere (I don’t know where, whether it was at the B-Course [the type conversion course] or [at his squadron,] the 90th) to initiate [rotation] – if you have a 136 [rotation speed], kind of standard below 2,000 feet – that you initiate aft stick pressure at 120 so that the nose is up at that rotation speed, and that has been my habit pattern.

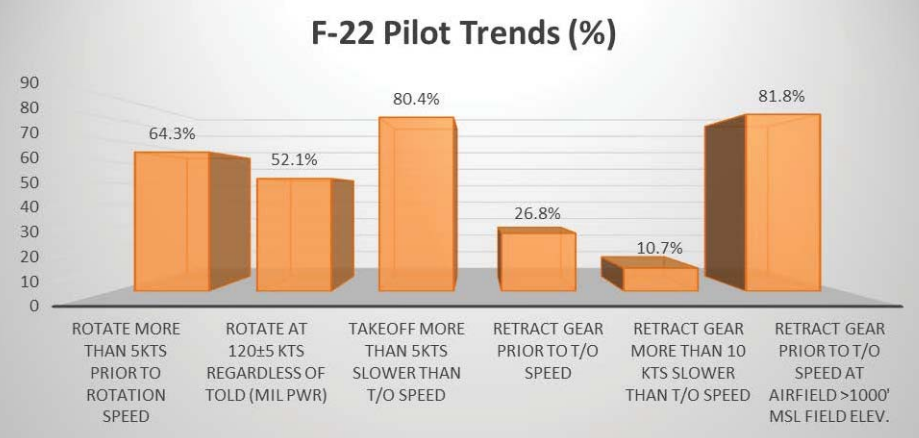

This technique was not limited to one pilot. In 64.3% of 56 sorties sampled, rotation was initiated greater than 5 knots prior to the calculated rotation speed and in 52.1%, rotation occurs at 120±5 KCAS (as per the accident pilot).

All pilots who were interviewed noted that they check their TOLD before takeoff. After the mishap, at a pilot meeting attended by 20 to 30 F-22 pilots, about half noted that they consistently use an early rotation technique. There is a clear trend of rotating early among a significant number of F-22 pilots…despite being aware of computed TOLD.

The investigators note that every F-22 base (with the exception of Nellis AFB) is at sea level, so “F-22 pilots do not have much experience taking off at high elevation airfields”. When data for high altitude airfield take-offs was examined: “every pilot continued to fly the aircraft as if he were taking off at his home airfield”.

There was a clear trend of rotating early among a significant number of F-22 student pilots at the B-Course. So why? The investigators say:

Most pilots acknowledged that the high thrust of the [F-22A] provides confidence that the jet will easily get airborne. One pilot commented that the F-22 community “takes it for granted that we have a lot of power and that this jet will generally take off from any runway that you want it to take off from”. Another commented, “I can’t think of a time where I’ve been concerned with TOLD . . . based on the thrust available”. Multiple pilots, including the [accident pilot], noted that the TOLD is emphasized more in the T-38 community than the F-22. Due to the lower thrust to weight ratio of the T-38, adherence to TOLD is more critical for safety of flight. There is a clear perception among F-22 pilots that the aircraft has sufficient thrust and braking capability to overcome deviations from TOLD. This perception has led to a decreased emphasis on TOLD.

A high profile accident using incorrect data at a high altitude airfield has happened before in the USAF. On 14 September 2003, an inappropriate altitude was selected by a USAF Thunderbirds display pilot for a display at the appropriately named Mountain Home AFB in Idaho. According to the AIB report the pilot misinterpreted the altitude required to complete a “Split S” maneuver, making calculations based on an incorrect above-mean-sea-level altitude for the base. The pilot therefore incorrectly climbed to only 1,670 feet above ground level instead of 2,500 feet before initiating the pull down into the Split S manoeuvre. The $20.4mn F-16C, 87-0327, impacted the ground, though the pilot ejected.

Safety Actions

The USAF say that:

Following this incident, 3rd Wing leadership directed a comprehensive review of Takeoff and Landing Data (TOLD) and TOLD special interest items briefed on every flight. Furthermore, a review and debrief of takeoffs and landings was completed for all pilots to identify and eliminate any lingering improper techniques with regards to takeoff and landing.

Observations on this Accident, a Previous Event, Repair Implications and the State of the F-22A Fleet (UPDATED: 18 November 2018)

There is no comment in the report on why the trends identified retrospectively could not have been identified proactively from in-service data, e.g. by techniques such as Flight Data Monitoring, before damage to an expensive, $143mn, asset. The USAF have a Military Flight Operations Quality Assurance (MFOQA) Program but it is not clear if its applied to the F-22A fleet, despite the clear Return on Investment (RoI) benefits.

Indeed, there has been a similar accident before when a trainee pilot, on his third F-22 sortie, raised the landing gear prematurely during a touch and go landing on 31 May 2012 at Tyndall AFB, Florida. The aircraft, 02-4037, settled back on the runway and skidded about 3,400 feet. In that case:

The AIB president found clear and convincing evidence that the causes of the mishap were the pilot’s failure to advance the aircraft’s engines to military power and the pilot’s premature retraction of the landing gear during a touch-and-go landing.

Without sufficient thrust, the aircraft settled back to the runway, landing on its underside.

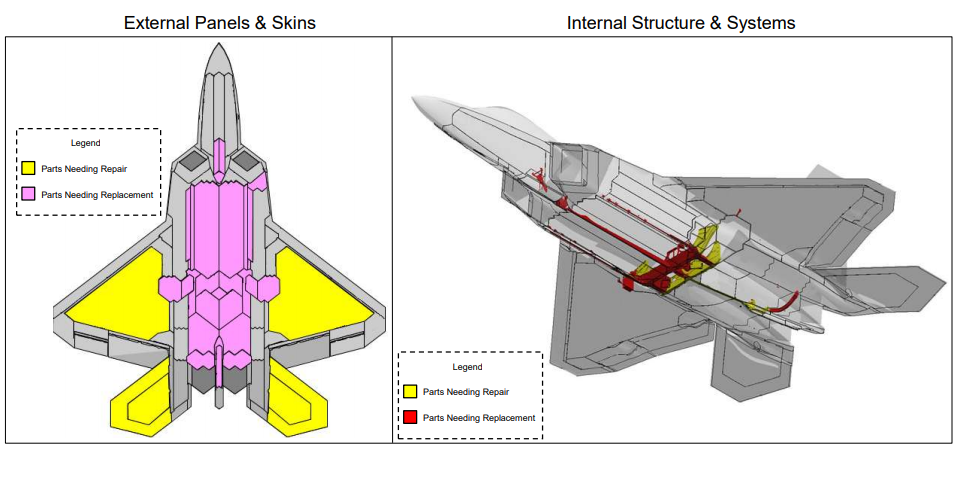

That investigation did not consider what was ‘normal’ in the fleet, only looking at the student pilots 6 landings/touch and goes, and so more systemic improvement opportunities were missed. The Tyndall accident aircraft was repaired after extensive work over 5 years. In addition to repairing surface damage wing and horizontal stabilisers, the USAF also replaced the skins and doors of the central and aft fuselage.

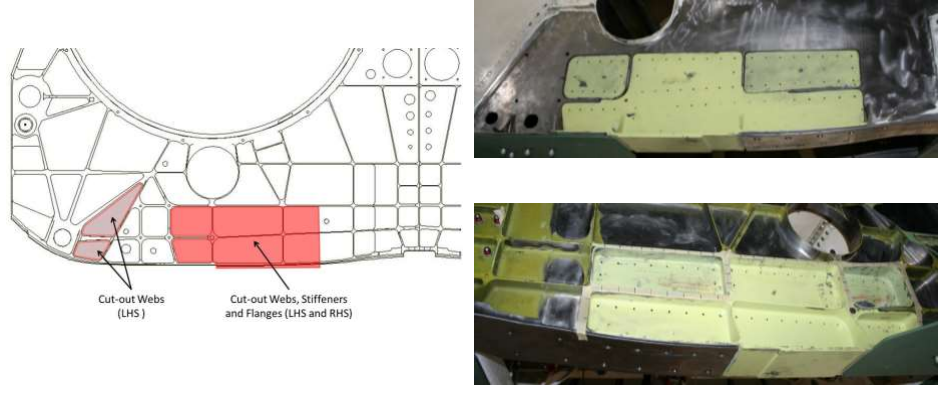

Impact load analysis identified that a fuselage bulkhead and a section of wing skin required titanium and carbonfibre patches. The most significant repair was however to a bulkhead at flight station 637, where buckled webs needed to be replaced.

FS637 Bulkhead Repairs to USAF F-22A Raptor 02-4037 after an Accident at Tyndall AFB on 31 May 2012 (Credit: USAF)

These repairs were estimated at c$35 million in total. Its disappointing that USAF AIB’s continue to label accidents, as they did in both cases here, simplistically as ‘pilot error’, even when noting in teh Fallon case that “organization factors contributing to this mishap were significant in influencing and shaping the [pilot’s] actions”. In the second report it is clear that the training system was inadequate and safety oversight poor, even after a prior accident.

The USAF had 186 operational F-22s when Hurricane Michael hit Tyndall AFB in October 2018. There were 55 F-22s based at Tyndall at the time, but 22 were unserviceable and had to be left on site to ride out the storm. It has been reported that 17 F-22s were damaged. The USAF has struggled to deploy and maintain the aircraft effectively, according to a Government Accountability Office (GAO) report: F-22 Organization and Utilization Changes Could Improve Aircraft Availability and Pilot Training.

Another 3rd Wing F-22A was involved in a landing accident at Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson, Alaska on 11 October 2018. This appeared to involve a failure of the left MLG.

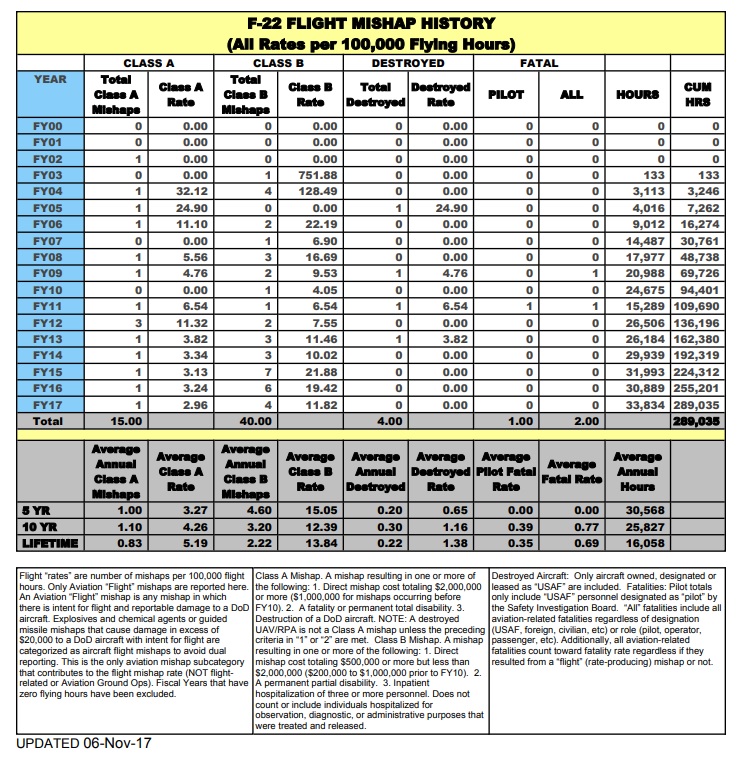

The latest F-22 mishap tabulation from the USAF Safety Centre is as follows:

In comparison the USAF Boeing F-15 Eagle mishap rates are:

- 10 Year Cat A: 1.83 (the F-22 is 232% higher)

- 10 Year Destroyed: 1.3 (the F-22 is 77% lower)

- Lifetime Cat A:2.34 (the F-22 is 221% higher)

- Lifetime Destroyed: 2.72 (the F-22 is 49% lower)

Two observations are, that:

- A Cat A mishap is defined partly by cost and so the F-22s high basic cost, expensive low observable coatings and radar cross section impact of damage and repairs on the F-22 would drive many repairs to be more expensive and so more incidents fall into that category.

- Equally, the high basic cost and smaller, out of production fleet size may mean more extensive repairs are still considered worthwhile, so fewer badly damaged aircraft are struck off charge as destroyed.

Safety Resources

You may also be interested in these Aerossurance articles:

- How To Develop Your Organisation’s Safety Culture positive advice on the value of safety leadership and an aviation example of safety leadership development.

- How To Destroy Your Organisation’s Safety Culture a cautionary tale of how poor leadership and communications can undermine safety.

- James Reason’s 12 Principles of Error Management

- Back to the Future: Error Management

- Complacency: A Useful Concept in Safety Investigations?

- Safety Intelligence & Safety Wisdom

- HROs and Safety Mindfulness

- Consultants & Culture: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly

And

- Yuma Hawk Accident: Lessons on Ex-Military Aircraft Operation – another case of early rotation

- USMC CH-53E Readiness Crisis and Mid Air Collision Catastrophe

- Inadequate Maintenance, An Engine Failure and Mishandling: Crash of a USAF WC-130H

- Culture + Non Compliance + Mechanical Failures = DC3 Accident

- Business Aviation Compliance With Pre Take-off Flight Control Checks

- RCAF Production Pressures Compromised Culture

- Loss of RAF Nimrod MR2 XV230 and the Haddon-Cave Review

- All Aboard CFIT: Alaskan Sightseeing Fatal Flight

- Investigators Criticise Cargo Carrier’s Culture & FAA Regulation After Fatal Somatogravic LOC-I

- AC-130J Prototype Written-Off After Flight Test LOC-I Overstress

- C-130 Fireball Due to Modification Error

- C-130J Control Restriction Accident, Jalalabad

- Crossed Cables: Colgan Air B1900D N240CJ Maintenance Error

- HF Lessons from an AS365N3+ Gear Up Landing

- Korean T-50 Accident at Singapore Airshow

- ‘Procedural Drift’: Lynx CFIT in Afghanistan

- UPDATE 18 December 2018: USAF Engine Shop in “Disarray” with a “Method of the Madness”: F-16CM Engine Fire

- UPDATE 26 December 2018: Inadequate Maintenance at a USAF Depot Featured in Fatal USMC KC-130T Accident

- UPDATE 26 January 2019: MC-12W Loss of Control Orbiting Over Afghanistan: Lessons in Training and Urgent Operational Requirements

- UPDATE 30 March 2019: Contaminated Oxygen on ‘Air Force One’ Poor standards at a Boeing maintenance facility resulted in contamination of two oxygen systems on a USAF Presidential VC-25 (B747).

- UPDATE 30 October 2019: ‘Crazy’ KC-10 Boom Loss: Informal Maintenance Shift Handovers and Skipped Tasks

- UPDATE 4 October 2020: Investigators Suggest Cultural Indifference to Checklist Use a Factor in TAROM ATR42 Runway Excursion

- UPDATE 25 April 2021: A Second from Disaster: RNoAF C-130J Near CFIT

- UPDATE 5 June 2021: SAR AW101 Roll-Over: Entry Into Service Involved “Persistently Elevated and Confusing Operational Risk”

- UPDATE 3 October 2021: French Cougar Crashed After Entering VRS When Coming into Hover

- UPDATE 14 May 2022: Review of “The impact of human factors on pilots’ safety behavior in offshore aviation – Brazil”

- UPDATE 2 January 2025: Startled Shutdown: Fatal USAF E-11A Global Express PSM+ICR Accident

- UPDATE 9 August 2025: OceanGate Titan: Toxic Culture & Fatal Hubris

- UPDATE 20 September 2025: Cold Comfort Conference Call: USAF F-35A Alaska Accident

Recent Comments