Grand Canyon Air Tour Tailwind Tragic Landing Accident (Papillon Airbus EC130B4 N155GC)

On 10 February 2018 Papillon Airways Airbus Helicopters EC130B4 N155GC was destroyed in an accident within the Grand Canyon, near Peach Springs, Arizona during an air tour flight. Five of the occupants, British tourists, died. The pilot and one passenger sustained serious injuries. Although there was a loss of control, this accident has many potential systemic lessons.

The Accident

The US National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) explain in their safety investigation report, released in January 2021, that this was the pilot’s third flight of the day from Boulder City Municipal Airport (BVU), Nevada. The last two were both to a site called Quartermaster, within the Grand Canyon‘s Quartermaster Canyon.

The 600 x 150 ft landing area is on rough ground on a plateau at an elevation of 1,450 ft amsl, approximately 3,300 ft below the rim of the Grand Canyon. It provided limited approach options due to its topography.

The area had no designated pads or marked touchdown and lift off (TLOF) zones, or any other fixed means (such as lines of rocks or marker stakes) for delineating preferred landing zones or maneuvering areas.

Papillon has started operating to the site in 1997. Their annual passengers numbers to the site grew from 11,305 in 1999 to 77,742 in 2017, with just over 1 million passengers and 179,661 flights in total prior to the accident, the first near the site. The NTSB report that:

The operator did not issue any written guidance to its pilots regarding specific approaches, approach profiles, or landing pads to use under certain conditions.

The pilot (41 years old part-time employee with 2423 total flying hours, 1079 on type) had flown passengers into the Grand Canyon 836 times for Papillon Airways and made 581 landings at Quartermaster.

Multiple Papillon pilots stated that the winds at Quartermaster were unpredictable and that the wind direction could drastically change during an approach into the landing site.

A prior “urgent Weather Message” was issued by the National Weather Service (NWS) at 1008 that wind would increase in the late afternoon, peak overnight, and decrease the following morning.

A Graphical Forecast for Aviation was issued about 1500 and valid for 1700 that depicted clear sky conditions, a surface visibility of greater than 5 statute miles, and northwesterly surface wind gusts between 20 and 35 kts in the accident region.

At 1700, the Papillon [weather] station [2 miles NNW] reported wind from the NNW at 11 kts; at 1710, the wind was from the NNW at 11 kts gusting to 19 kts. At 1720, the wind was from the N at 11 kts, and at 1730, the wind was from the NNW at 12 kts, gusting to 24 kts.

The company operations manual imposed maximum wind limitations of 30-35 kts steady wind and a gust spread of 20 kts or greater[sic]; these limitations applied to both on- and off- airport operations.

Sunset was at 1711 and dusk was at 1738 [implying night flying to return].

The accident flight departed at 1642 Local Time, reached the Hoover Dam at about 1652 and entered the helicopter route “Green 4”.

Radar coverage was lost at 1717, about 3.5 nm west of the accident site as the helicopter descended into the canyon.

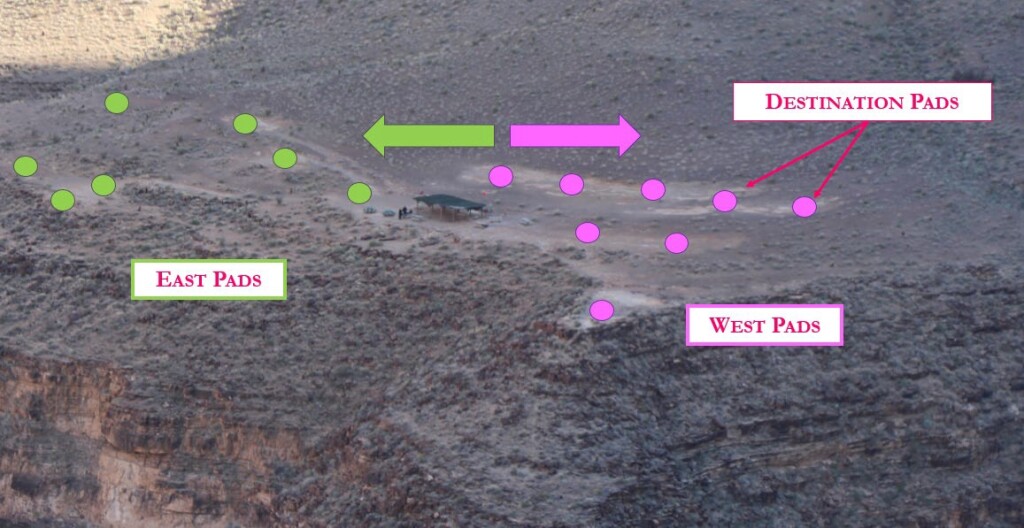

The operator had planned for 10 helicopters to arrive sequentially at Quartermaster.

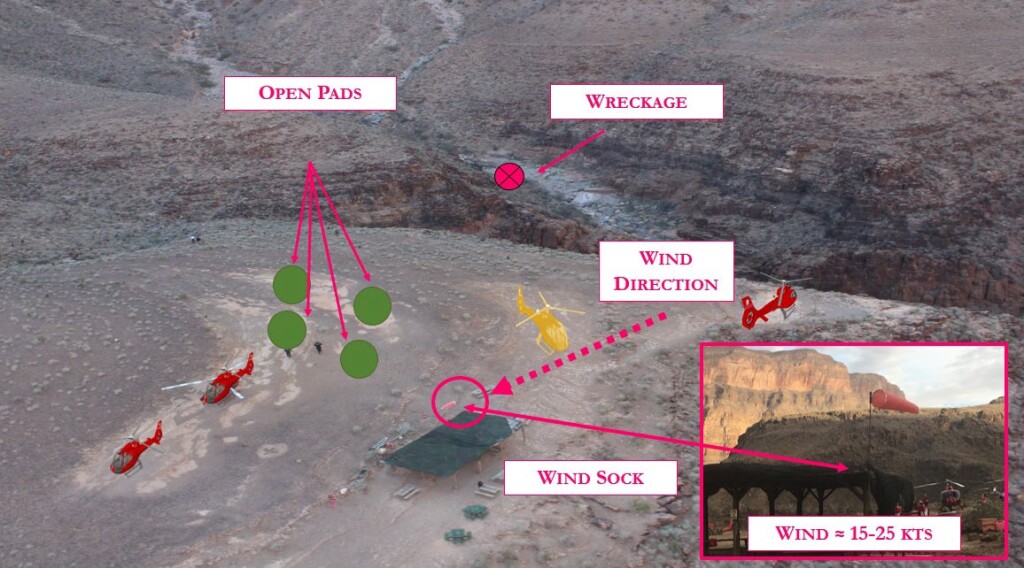

The accident pilot stated that, during the approach to Quartermaster, he noted that the eight helicopters that had already landed were facing in different directions, indicating variable wind conditions. The combination of the windsock direction, orientations of the parked helicopters, and unoccupied landing pads on the west side of the landing area prompted the pilot to conduct an approach from the west and touch down on one of the west landing pads.

He recalled that the two helicopters that landed immediately before him were on the west landing pads facing east, the same as his chosen approach direction, and noted that the windsock indicated wind from the NNE.

However:

Photographs of the landing site windsock near the time of the accident indicated winds at magnitudes of 15 kts or greater from the NNW.

Windsock at Papillon Quartermaster Landing Area, Grand Canyon Just Prior to Accident (Credit: via NTSB)

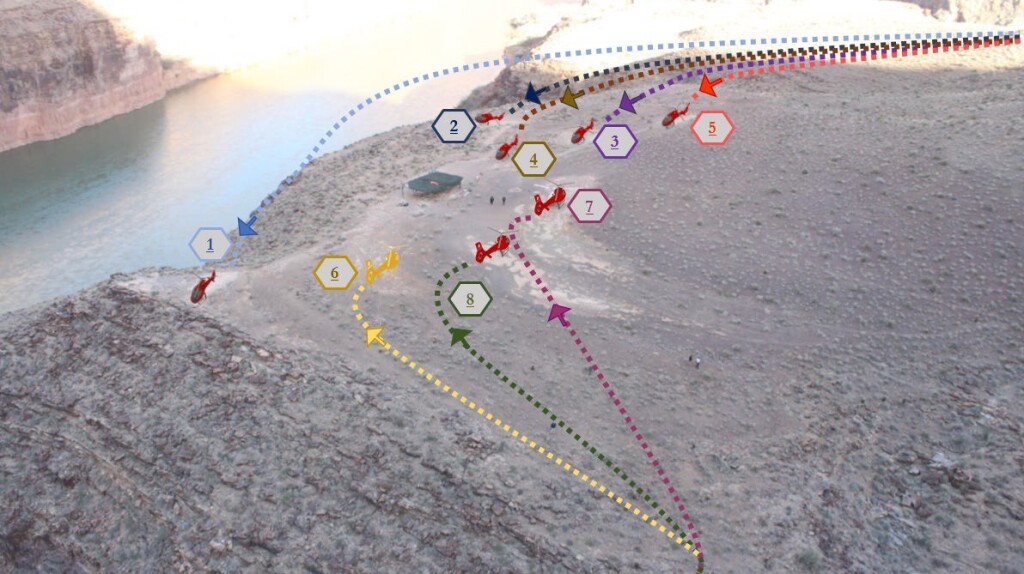

The pilot stated that he normally remained on the north side of the Colorado River, crossing the river between 200 and 300 ft above ground level (agl) while approaching Quartermaster for landing. After crossing the river, he entered a left turning descent toward the landing area.

Direction of Approach of Papillion Airbus EC130B4 N155GC, to Quartermaster, Grand Canyon (Credit: NTSB)

This meant it was a tailwind approach.

Direction of Approach of Papillon Airbus EC130B4 N155GC, to Quartermaster, Grand Canyon (Credit: NTSB)

A Papillon pilot on the ground at Quartermaster watched the accident helicopter as it approached from across the river and assumed that the pilot planned to land on the west pads based on his approach path. He reported that the helicopter decelerated and then entered an approximate 15° nose-up pitch attitude. While maintaining altitude, the helicopter began a left turn toward the landing site. According to the witness, during the turn, the helicopter transitioned into a level attitude, followed by a nose-low attitude. [T]he helicopter began to drift aft as the left turn continued and returned to a level attitude before it rotated 360° and began a descent.

Representation of Witness’ Observation of Papillon Airbus EC130B4 N155GC Approaching Quartermaster, Grand Canyon (Credit: NTSB)

After a second 360° rotation, the helicopter collided with terrain.

[The pilot] stated that, as he made the left turn, the helicopter encountered what he described as a “violent gust of wind” and began to spin, and as a result he was unable to maintain directional control.

The helicopter came to rest upright in rocky terrain about 300 ft below the landing site… A post-impact fire ensued.

Survivability and Emergency Response

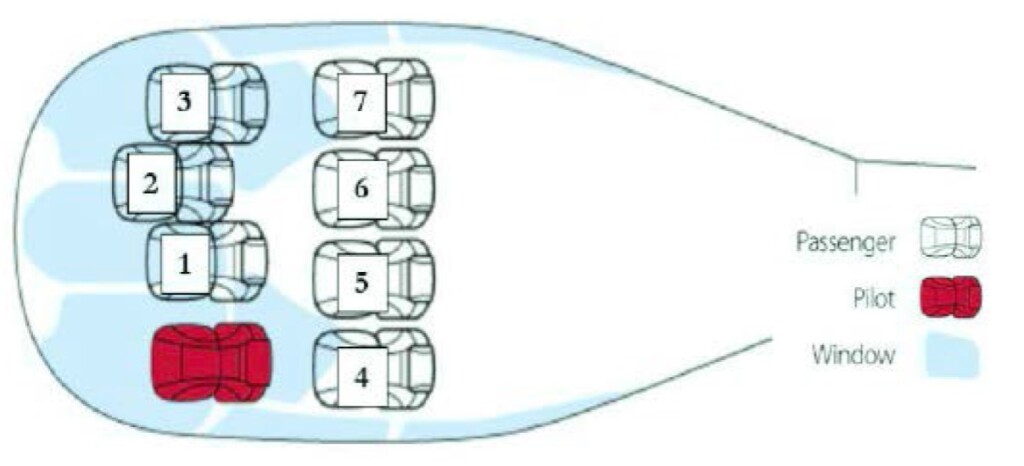

Passengers in seat Nos. 2, 6, and 7 did not have either the ability or opportunity to evacuate and died due to burns and smoke inhalation injuries; no blunt force traumatic injuries were noted by the medical examiner.

The pilot and passengers in seat Nos. 3, 4, and 5 sustained serious thermal injuries. Passengers in seat Nos. 3 and 4 succumbed to their burn injuries several days after the accident.

In addition to their thermal injuries, the passenger in seat No. 5 sustained a spinal fracture. The pilot sustained an open left leg fracture.

On October 3, 1994, the FAA introduced improved fuel system crash resistance standards for newly certified normal category helicopters [27.952]…however, they were not retroactively applicable to either existing helicopters or newly-manufactured helicopters whose certification and approval predated the revised standards.

As the EC130B4’s certification basis pre-dated that requirement, N155GC, manufactured in 2010, was not required to meet 27.952. Retrofittable systems became available in 2017.

Papillon Airbus EC130B4 N155GC on Fire, near Quartermaster, Grand Canyon – Seen from Another Helicopter (Credit: NTSB)

Immediately, after the accident…

Several Papillon pilots and members of the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) [presumambly there as tour passengers] retrieved first aid kits from other helicopters and responded to the accident site, arriving about 20 minutes after the accident.

They observed the burning helicopter and the pilot and three seriously injured passengers who were outside the helicopter.

A box containing medical supplies had to be smashed open because no one knew the combination to the lock. Communications using satellite phones provided at Quartermaster proved problematic due to “dead batteries, poor coverage, and a lack of training in their operation”. This created confusion about the number of victims and stranded passengers.

The helicopter was equipped with an Artex C406-N HM emergency locator transmitter (ELT), which transmitted an alert notification and location information to the Air Force Rescue Coordination Center (AFRCC) at 1719:42.

Emergency responders from Grand Canyon West Airport arrived at Quartermaster by helicopter about 45 minutes later. However, the accident location access meant that:

The seriously injured occupants were eventually extracted from the accident site via helicopter between 2315 and 0105 arriving at University Medical Center in Las Vegas between 0055 and 0128.

Shuttle flights for stranded Papillon passengers [from other flights] at the Quartermaster landing zone continued until pilot fatigue became an issue. At that point flights ceased, and several passengers spent the night sheltering in helicopters at Quartermaster.

NTSB Investigation and Analysis

Postaccident examination of the helicopter and engine revealed no evidence of mechanical anomalies that would have precluded normal operation.

[T]he operator required a minimum of 1,000 hours of pilot-in-command helicopter time before their employment.

The investigators comment that:

When asked how they trained their pilots in mountainous flight operations, the company’s Director of Operations stated that “all of our pilots come to us as commercially rated pilots proficient in these maneuvers and certified to competency by the FAA in rotorcraft.”

The company’s EC130B4 initial training includes pinnacle and confined space operations as two of 8 topics in a single, 1.3-hour instructional flight.

The Lead Pilot that conducted the [accident] pilot’s recurrent training on December 20, 2017 recalled that the day of the training flight was very windy, with gusts up to 30 kts. After completing the 1.7-hour flight he marked the flight as “unsatisfactory” performance, which was only the second pilot he had ever failed since being employed at Papillon.

He stated that he didn’t pass the pilot because of his inadequate performance of practice autorotations. Specifically, the pilot was having difficulty with maneuvering the helicopter in wind and not having enough altitude when turning during 180-degree autorotations. After the pilot repeatedly could not perform to the Lead Pilot’s standards, the Lead Pilot prematurely ended the flight.

After the flight, the Lead Pilot debriefed the Chief Pilot about the flight and informed him on the areas that the pilot needed to improve. According to the paperwork either the next day or 2 days after, the pilot flew 0.7 hours, passing his check ride with a different Lead Pilot.

NTSB explain that on the afternoon of the accident, significantly…

The pilot who landed just before the accident reported [to NTSB] that he encountered wind conditions that necessitated full right pedal and nearly resulted in a loss of yaw control. The accident helicopter’s flight characteristics at the time of the accident would have included slowing airspeed, a high power setting, and a relative wind position that were all conducive to a loss of tail rotor effectiveness (LTE), thus it is likely that the loss of control was the direct result of LTE.

This was not shared by radio with other inbound pilots as a warning. An agreement was in place between the local air tour operators in the Grand Canyon to “avoid unnecessary radio chatter”.

The NTSB further note that:

At the time of the accident, potential demarcation lines (boundaries of updrafts and downdrafts) would have been on the pinnacles of ridges located along the approach to the Quartermaster west pads.

The following NTSB ‘conceptual illustration’ of contemporary conditions shows where airflows could have affected the approach.

Likely Airflow During Approach of Papillon Airbus EC130B4 N155GC, to Quartermaster, Grand Canyon (Credit: NTSB)

NTSB comment that individual windsocks can’t indicate the presence of updrafts, downdrafts, turbulence, or any other local aerodynamic effects. They state that:

Weather advisories issued after the morning weather briefing…was likely not captured by the operator and distributed to its pilots even though some of the forecasts included wind conditions above the maximum wind outlined in the company’s general operations manual (GOM).

The investigators note that Airbus Safety Information Notice 3297-S-00 discusses “the detection and recommended response to unanticipated yaw, emphasizing”:

If unanticipated yaw occurs, react immediately and with large amplitude opposite pedal input. Be ready to use full pedal, if necessary. Do not limit yourself to what you feel sufficient, your feeling can be wrong. Never bring the pedal back to neutral before the yaw is stopped

The investigators also note the challenges accessing the remote accident site and note that:

The most significant factor affecting occupant survival was the immediate postcrash fire.

However, in the absence of crash dynamics and impact force data, the NTSB were unable to say if a crash-resistant fuel system would have prevented a post crash fire.

NTSB Probable Cause

A loss of tail rotor effectiveness, the pilot’s subsequent loss of helicopter control, and collision with terrain during an approach to land in gusting, tailwind conditions in an area of potential downdrafts and turbulence.

Papillion: Organisation, SMS, Culture and Post-Accident Safety Actions

Family run Papillon was established in 1965. It is one of the largest Nevada air tour operators. This was their fatal accident since 10 August 2001 when AS350B2 N169PA crashed in Arizona with the loss of 6 lives. In that case the NTSB reported that:

…the probable cause of this [2001] accident was the pilot’s decision to maneuver the helicopter in a flight regime and in a high density altitude environment which significantly decreased the helicopter’s performance capability, resulting in a high rate of descent from which recovery was not possible.

That aircraft was destroyed by the post crash fire. The NTSB did discuss the fuel system certification requirements but made no recommendations at the time. They did in April 2016, after another accident that was caught on CCTV: Crashworthiness and a Fiery Frisco US HEMS Accident (N390LG).

While not required by FAA regulations, Papillon employs a full-time Director of Safety who routinely conducted audits of company operations and administers Papillon’s Safety Management System (SMS) program. In addition, Papillon brought in an independent safety auditor each year to assure full compliance with FAA regulations.

Papillon was a founding member of TOPS (Tour Operators Program of Safety) whose members abide by strict self-imposed regulations and was also International Standard for Business Aircraft Operations (IS-BAO) certified…

TOPS goes beyond the requirements of the Federal Aviation Regulations (FARs) for Part 91 and Part 135 operations, under which most tours are conducted. The following table illustrates some of the TOPS safety requirements that exceed FAA regulations.

Non-US readers might be surprised at some basic items that are not required Part 135!

The NTSB summarise some details of the operator’s voluntarily implemented SMS but do not appear to have assessed its performance beyond…

A review of the 242 Irregularity Reports in the two years prior to the accident disclosed that 109 of the reports were weather related, of which 5 of those pertained to wind. The month prior to the accident a report was filed for an over limit due to a large wind shift at Quartermaster.

There is no further comment on this or on ant risk assessments conducted by the company on operations to Quartermaster or crash-resistant fuel systems. No detail is provided on their extant emergency response plans.

After the accident NTSB conducted extensive interviews (accumulating 796 pages of interview transcript). They asked several interviews what they thought of the organisation’s safety culture and based on that methodology concluded encouragingly that:

Pilots felt that safety was a priority with management and they did not feel pressured to take or continue a flight that was not safe.

After the accident Papillon…

…expanded the existing LTE training module in pilot training syllabus.

…installed an additional windsock near the accident site along with a weather station that transmits real-time wind information to Papillon’s base of operations.

…upgraded their Spidetracks program, a GPS tracking platform, from a sampling rate of 15 minute intervals to 15 second intervals.

…trained 12 employees as emergency response instructors to develop a module for employee training.

…purchased new satellite phones with improved coverage, easier operability, and spare batteries. Papillon pilots were trained in their use and asked to demonstrate their proficiency in using the satellite phones.

…purchased trauma kits and a collapsible stretcher that are now located in unlocked metal containers, readily available for emergency crews.

…provided its pilots with first aid training and developed procedures to inspect the emergency medical equipment quarterly.

A modification to retrofit the EC130B4 with a crash-resistant fuel system was approved by the FAA in December 2017. The NTSB comment:

According to the operator, the retrofit kits were not available to them until April 2018, after which they completed a retrofit of their existing fleet of EC130B4 and AS350-series helicopters by August 2018.

A press release dated 26 February 2018 stated that StandardAero and Papillon Airways signed a memorandum of understanding for 40 retrofitted systems. This was on the eve of the HAI Heli-Expo in Las Vegas, a traditional time to hold press releases for. It is not clear when negotiations started.

UPDATE 24 November 2021: At an inquest into the death of the passengers the West Sussex Coroner directs recommendations to UK CAA.

UPDATE 10 January 2024: Airbus Helicopters settles Grand Canyon crash lawsuit for $75m

The settlement, agreed before a Clark County district judge on 5 January, stipulates that Airbus Helicopters pay $75.4 million and Papillon $25.4 million.

According to legal research service VerdictSearch, the $100 million settlement is the ”highest pretrial settlement amount in its database for a single wrongful death case”. The case had been scheduled to go to trial on 6 February and last six weeks.

Safety Resources

Airbus have discussed unanticipated yaw phenomena and the ‘myth of LTE’ here:

The European Safety Promotion Network Rotorcraft (ESPN-R) has a helicopter safety discussion group on LinkedIn.

ESPN-R / EHEST Leaflet HE7: Techniques for Helicopter Operations in Hilly and Mountainous Terrain

You may also find these Aerossurance articles of interest:

- Fatal $16 Million Maintenance Errors (US air tour AS350)

- NTSB Reveal Lax Maintenance Standards in Honolulu Helicopter Accident (US air tour B206)

- Torched Tennessee Tour Trip (US air tour B206)

- Regulator Missed the Chance to Intervene Before Fatal Tour Accident say TAIC (NZ air tour AS350)

- All Aboard CFIT: Alaskan Sightseeing Fatal Flight (US air tour aeroplane)

- Too Extreme: Fatal Sky Combat Ace EA300 Aerobatic Accident

- Crashworthiness and a Fiery Frisco US HEMS Accident

- Hawaiian Air Tour EC130T2 Hard Landing after Power Loss (Part 1)

- Hawaiian Air Tour EC130T2 Hard Landing after Power Loss (Part 2 – Survivability)

- Offshore Helicopter Accident Ghana 8 May 2014 & The Importance of Emergency Response

- Fatal Night-time UK AW139 Accident Highlights Business Aviation Safety Lessons

- CFIT Gangnam Style – Korean S-76C++ and Decision Making

- That Others May Live – Inadvertent IMC & The Value of Flight Data Monitoring

- UPDATE 23 January 2021: US Air Ambulance Near Miss with Zip Wire and High ROD Impact at High Density Altitude

- UPDATE 29 January 2021: BK117 Impacts Sea, Scud Running off PNG

- UPDATE 31 January 2021: Fatal US Helicopter Air Ambulance Accident: One Engine was Failing but Serviceable Engine Shutdown

- UPDATE 5 March 2021: Wire Strike on Unfamiliar Approach Direction to a Familiar Site

- UPDATE 21 May 2021: Firefighting AW139 Loss of Control and Tree Impact

- UPDATE 3 July 2021: EC130 Door Loss Damaged Main Rotor Blades

- UPDATE 3 October 2021: French Cougar Crashed After Entering VRS When Coming into Hover

- UPDATE 21 December 2021: R44 Unanticipated Yaw Accident During Tailwind Take Off Caught on Video

- UPDATE 23 December 2021: Air Methods AS350B3 Air Ambulance Tucson Tail Strike

- UPDATE 18 June 2022: Limitations of See and Avoid: Four Die in HEMS Helicopter / PA-28 Mid Air Collision

- UPDATE 25 June 2022: NYPD B429 Accident at Manhattan Heliport “Overapplication of Flight Controls”

- UPDATE 2 July 2022: Fatal EC130B4 Water Impact in the Tennessee River after “Entry to VRS” Say NTSB

We have discussed human factors and error management more generally here:

- Professor James Reason’s 12 Principles of Error Management

- Back to the Future: Error Management

- Also see our review of The Field Guide to Understanding Human Error by Sidney Dekker presented to the Royal Aeronautical Society (RAeS): The Field Guide to Understanding Human Error – A Review

A public inquiry chaired by Anthony Hidden QC investigated 1988 Clapham Junction rail accident. In the report of the investigation, known as the Hidden report, he commented:

There is almost no human action or decision that cannot be made to look flawed and less sensible in the misleading light of hindsight. It is essential that the critic should keep himself constantly aware of that fact.

Recent Comments