Regulator Missed the Chance to Intervene Before Fatal Tour Accident say TAIC

On 21 November 2015 Airbus Helicopters AS350BA ZK-HKU, of Fox and Franz Heli Services. was conducting scenic flights out of the operator’s base near Fox Glacier town.

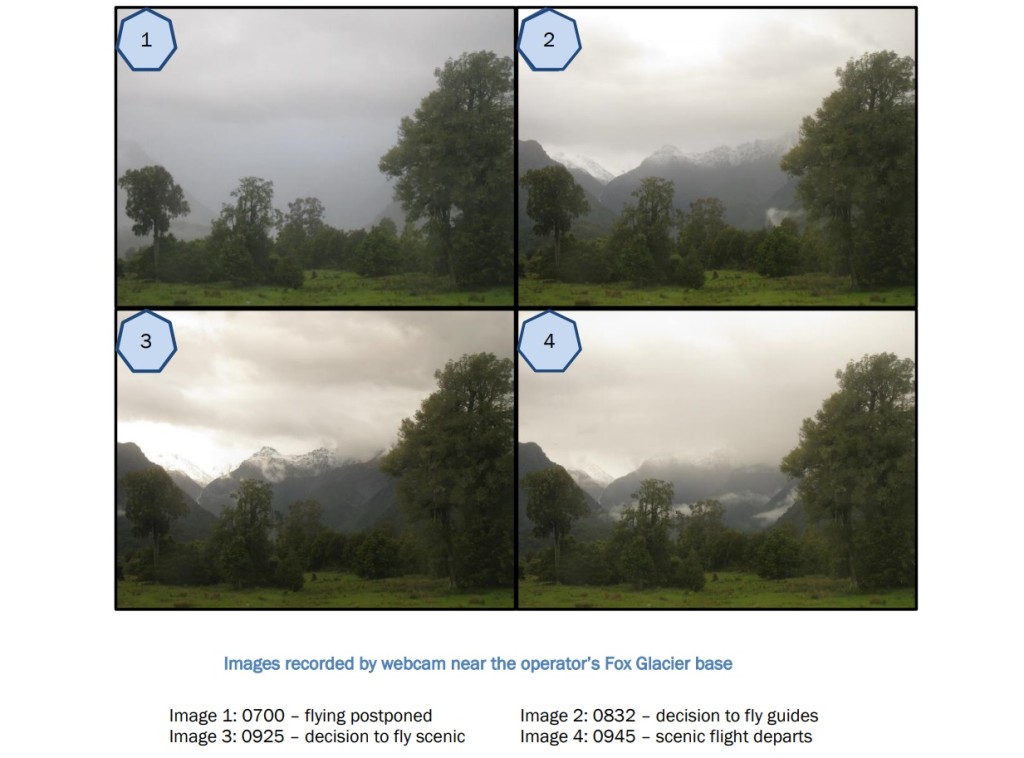

Heavy rain had caused the cancellation or postponement of several flights, but after a shorter flight to the lower part of Fox Glacier (also known as Te Moeka o Tuawe) the 28 year old pilot decided that the weather had improved enough to conduct a flight to the head of the Fox Glacier valley. At 0945 the helicopter departed for a 20-minute flight with seven people on board (the pilot, two Australian tourists and 4 from the UK) .

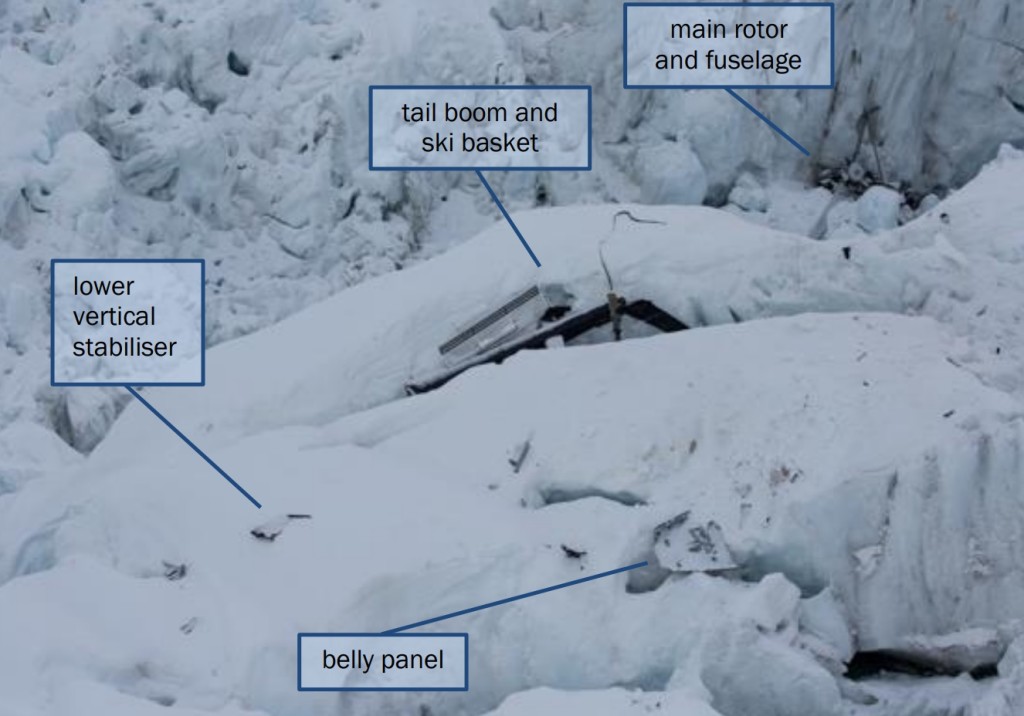

The flight was reported overdue at 1015. The wreckage was subsequently located on the glacier just below Chancellor Shelf (which is about 5,600 feet above sea level).

There were no survivors. The helicopter was destroyed.

The New Zealand Transport Accident Investigation Commission (TAIC) say in their accident report that physical evidence indicated that “the helicopter hit the ice in a relatively level attitude with a very high rate of descent” and “relatively high forward speed”. There were indications that main rotor speed hap drooped.

The helicopter was not equipped with the instruments necessary for safe flight in low or no visibility, and the pilot was not trained for instrument flying.

Passenger photos and a webcam at the company base showed the flight had departed Fox Glacier town in light rain and overcast conditions, with some low cloud.

The flight encountered heavy rain later on.

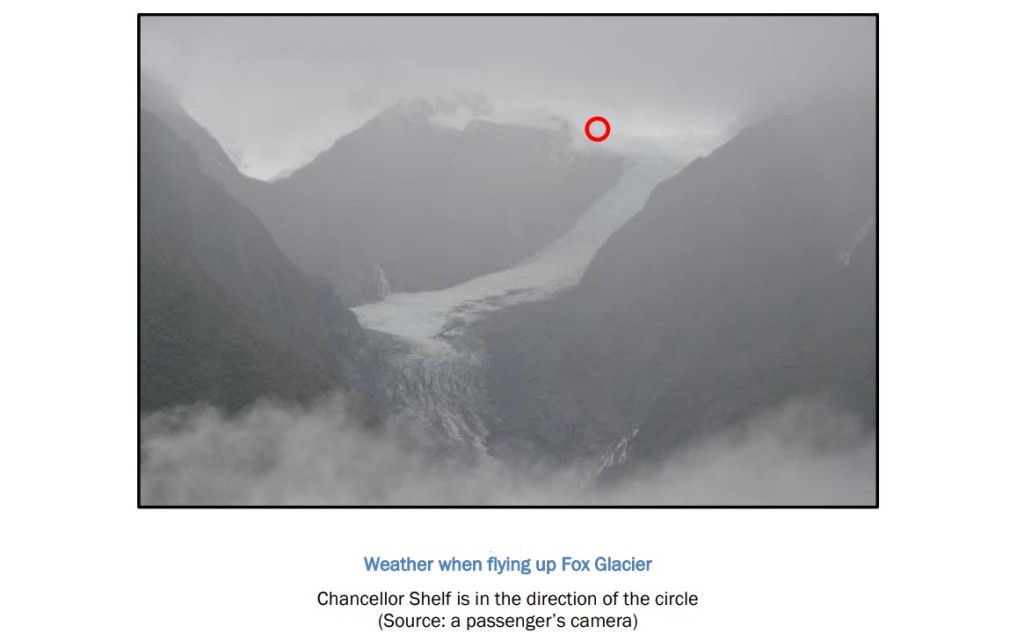

Approaching Chancellor Shelf there was low cloud just above with some cloud spilling down the mountain.

The helicopter had landed on Chancellor Shelf and the passengers had got out to walk in the snow. It was snowing at the time and cloud was coming and going in the general area.

The lower valley was partly visible in one view, which suggested a visibility greater than the minimum 1,500 m required for visual flight rules. In other directions the flat light allowed little or no distinction between the surface and the cloud.

There was no recorded evidence of the helicopter’s flight path after it departed Chancellor Shelf…unusual for tourists on a scenic flight. It suggests that the visual conditions might not have been ideal for photography.

The aircraft took off from Chancellor Shelf at an estimated 47 kg over weight, having departed the operator’s base 65 kg overweight. In addition:

The tail rotor hydraulic servo was due for overhaul at 13,741 airframe hours. On 24 April 2015 the contracted maintenance organisation had extended the servo replacement to 13,921 hours [i.e. by 160 hours], as allowed by the Civil Aviation Rules and the approved maintenance programme. The helicopter had accrued 13,959 flight hours as at 19 November 2015… [so] the servo had remained in service for 38 hours beyond…the maximum flight hours permitted before overhaul…

TAIC note that these facts were unlikely to have been factors in the accident. The overweight operation and component over run might suggest weaknesses in the operator’s organisation however.

The Operator’s Organisation

Formed in 1986, the Alpine Adventures company owned by JP Scott (also trading as Fox and Franz Heli Services, Tekapo Helicopters and Makarora Helicopters) had “a fleet of 13 helicopters and employed nine full-time pilots, four part-time pilots and 24 ground staff.” At the time of this accident the operator had one of the largest helicopter fleets in New Zealand.

Their main business was glacier scenic flights and charters for climbing, hunting and fishing trips. The owner was the chief executive and the holder of an Air Operator Certificate (AOC) issued under Civil Aviation Rules Part 119 and the company was operating under Part 135 rules.

The Training Manager described the operator’s training programme as being merely an “informal plan” for the training of pilots who were new to the company or inexperienced. The operator did not have a mountain flying training programme (though NO organisation had been NZ CAA approved for mountain training!).

In practice, the Training Manager, appointed in 2008 while working overseas a month on / a month off as a ‘touring pilot’ for another operator, had since taken a full-time job as a Training Manager with another NZ CAA approved operator in April 2009. They conducted their last training for the operator in January 2012 and had “little contact with the operator after 2012”, but formally remained the Training Manager in the exposition.

The operator did have Training Supervisor, appointed in 2013 and being “under the overall supervision of the Training Manager”. They “had not seen the Training Manager since mid-2013”. The Training Supervisor’s role and duties were not shown in the operator’s exposition until a revision prepared in November 2015. Their understanding was that having a Category D flight instructor rating permitted them to conduct certain types of flying training and “CAA inspectors had given conflicting advice…on whether that training was permitted”. The Training Supervisor also managed day-to-day company activities with the Franz Josef office manager (who TAIC say “was not qualified to supervise operations”).

Apart from safety meetings there is no mention of any other safety management activity in the TAIC report.

The Operator’s Accident Record

TAIC say that:

In 1989 two passengers had died when one of the operator’s helicopters crashed during a scenic flight over Fox Glacier. The other two occupants had been seriously injured. The helicopter had been flown below the minimum permitted height above ground.

In the six years prior to this accident the company had one helicopter roll over after a forced landing following an engine failure in September 2009, one struck the ground and rolled over during a go around in November 2012 and one crashed, with two serious injuries, on take off in June 2015. All three were at mountain landing sites.

It should be noted that a similar New Zealand operator also has a spate of accidents: Queenstown’s The Helicopter Line has four snow crashes in three years (October 2013, August 2014 and [subsequent to the Fox Glacier accident discussed here] September 2016). This indicates that the sectors was exhibiting a noticeably high level of risk.

The Pilot

The pilot had re-joined the operator in September 2014 with more than 1,200 hours’ helicopter experience, but only 8.5 hours on the AS350 helicopter, accrued over five years.

The training supervisor had recognised the pilot’s low experience, both on the AS350 type and with flying in the mountains. The training supervisor said the pilot was given the same training as other pilots and had “a very controlled progression” through the [operator’s] pilot categorisation system, but the training records and logged flights did not support that view.

The standard of the pilot’s operational performance was unclear because of conflicting records provided by the operator.

Up until the day of the accident the pilot’s logbook showed 1,792 hours’ total flight time, which included 415 hours on the AS350, of which 406 hours had been flown with the operator.

Regulatory Oversight

The NZ CAA had most recently re-issued the operator’s AOC with effect from 1 December 2012, following a full ‘recertification’ audit.

The CAA’s Helicopter and Agricultural Unit was responsible for the certification and surveillance of approximately 100 commercial operators of more than 200 helicopters. The unit had full-time positions for six flight operations inspectors and six airworthiness inspectors. This unit had been the primary CAA contact with the operator.

However, press reports suggest even fewer inspectors were actually assigned to helicopter operators at the time:

New Zealand had the highest number of helicopters per capita in the world, but only had two inspectors available to scrutinise their operations. The deputy director of general aviation Steve Moore said CAA had since quadrupled the number of helicopter operations inspectors from two to eight*, and strengthened their training following the crash. Those two inspectors had “big workloads” at the time and were responsible for conducting oversight of 100 or so helicopter operators, he said.

* CAA has since clarified it has five flight operations inspectors on staff. It has recently hired another inspector and has two vacancies. It has funding for eight positions.

TAIC go on:

A CAA audit report in March 2011 had noted that the Training Manager might have to be replaced should another employment offer be taken up. According to the audit report, the Chief Executive had acknowledged that need. The audit team had also discussed the possibility of someone other than the Chief Executive being Operations Manager, because the size and scope of the operation had increased. The Chief Executive had said that the Operation Manager position would be reviewed before the recertification due in 2012. The new certificate had been issued without any changes to the senior persons.

A CAA risk assessment prepared for an audit after the accident in 2012 noted potential risks in the areas of chief executive oversight, pilot supervision and the effectiveness of the lead pilot ([who subsequently took on the role of] Training Supervisor).

The Training Manager had not attended any of the [NZ CAA] audits between March 2011 and late 2015.

Informal notes made by the NZ CAA auditor during the March 2015 audit indicated that the auditor…

…determined that there was a low risk of a poor company culture, and that the training situation was “good”. The notes stated that the training supervisor had “made vast improvements” and that crew members were receiving “good practical recurrent training”. No findings were made at this audit.

The pre-audit risk assessment conducted suggests the NZ CAA thought the Training Manager was still a touring pilot (a post he gave up in April 2009, when he started full time as a Training Manager at another NZ operator). During this March 2015 audit an in-service aircraft was inspected that was not on the operator’s operations specifications, something TAIC say there was no evidence the auditor realised.

The NZ CAA had concerns following the non-fatal accident in June 2015.

Inspectors conducted a spot check in September and interviewed the Chief Executive and the Training Supervisor. The inspectors’ notes suggested that the training supervisor had in effect been acting as Training Manager. They noted [again] that the Training Supervisor had improved the operator’s performance. The CAA made no findings during the spot check.

Three weeks before the fatal accident another NZ CAA risk assessment…

…recorded, for the first time, that the training manager had little involvement with the operator and that it appeared that the Training Supervisor was carrying out the duties of this role. [It] included a statement that the training situation posed a high risk of an accident/incident, but noted [yet again] that the Training Supervisor had the requisite skill and experience.

However, no divisive action appears to have been taken by NZ CAA.

The assessment also recorded that there was “much debate” within the CAA about the exercise of Category D flight instructor privileges, because of different interpretations of some Civil Aviation Rules.

There is a dispute on whether the Training Supervisor was told to stop delivering training during a NZ CAA ‘spot check’ in September 2015 as there was no written records made by NZ CAA.

On 27 May 2016, 6 months after the accident, the Director of Civil Aviation suspended the operator’s AOC. The operator then surrendered the certificate. The CAA later stated to TAIC:

The CAA undertook its own investigation into this crash and subsequently successfully prosecuted the operator for not taking all practicable steps to ensure the safety of its pilot and his passengers.

This is despite key evidence already being in NZ CAA’s possession before the accident according to TAIC.

This prosecution was initiated in June 2016 under the Health and Safety in Employment Act 1992 and the owner pleaded guilty and was fined NZ$64,000 in the District Court in Christchurch on 17 May 2019. In the meantime, questions were raised in July 2017 about the conduct of the NZ CAA investigation and allegations a CAA investigator had embellished the qualifications on their CV, and that like the surveillance auditors, the investigator had not been compiling detailed notes. In 2018 the NZ CAA had prosecuted The Helicopter Line under the same legislation for failings that were agreed to been “not causative” to a 2014 accident.

In contrast TAIC noted that, perhaps rather surprisingly:

In September 2016 the CAA issued an AOC to a new company that took over from the former operator.

This company had the same owner, they were no longer a post-holder.

TAIC Analysis

TAIC consider “the weather conditions on the day were unstable and unsuitable for conducting a scenic flight. The localised weather conditions in the area were very likely to have been frequently below the minimum criteria required by the Civil Aviation Rules”. They go on:

The decision to continue with the scenic flight and make the landing was imprudent given the changeable conditions. The pilot was considered by others to be very confident, but a senior pilot commented that the pilot had at times shown a lack of awareness of how quickly the weather could change. Nevertheless, the pilot could have decided to turn back at any time while proceeding up the valley.

It is very likely that when the helicopter took off from Chancellor Shelf and descended down the valley, the pilot’s perception of the helicopter’s height above the terrain was affected by one or more of the following conditions:

– cloud

– precipitation

– flat light conditions

– condensation on the helicopter’s front windscreen.Given that the pilot had little more than one summer season of operational experience in the alpine region, the Commission considered the operator’s training system and how it prepared and assessed a pilot for increasing levels of responsibility. The Commission found that the pilot had not been properly trained and did not have the appropriate level of experience expected under the operator’s categorisation scheme for a senior pilot in this type of operation. The operator’s system for training its pilots was ill-defined and did not comply fully with the Civil Aviation Rules.

The operator’s training system did not have sufficient oversight by the designated senior persons, and this was a factor that allowed the pilot to be assigned roles and responsibilities without the proper training and experience. In spite of the Training Manager no longer having an active involvement, the Chief Executive had not mentioned this situation, even during the audit in March 2015 that examined pilot training. In January 2015 the operator had requested CAA approval to replace the Training Manager with either the Chief Executive or the Training Supervisor, but the application had been declined.

There were a number of serious and persistent issues with the senior management oversight of the operation.

The operator’s own audit programme had not identified these management and training issues (and their contracted quality manager ‘s company was also successfully prosecuted). However:

The Civil Aviation Authority had identified significant non-compliance issues with the operator’s training system and managerial oversight that had warranted intervention long before this accident occurred.

The CAA had commented on, and in some cases raised findings for, aspects of pilot training and competency checks after conducting audits of the operator in 2005, 2008, 2011, 2013 and March 2015. CAA staff were aware that the training supervisor had been conducting training, most likely since 2013, but they had made no specific finding of non-compliance during any audit between then and the accident in November 2015.

A NZ CAA letter letter to the operator claimed they had been “led to believe” at previous audits that the Training Manager was still acting in that role and have subsequently claimed they were lied to and stated their inspectors had been “too trusting” in accepting the operator’s reassurances. TAIC however concluded that “CAA auditors and inspectors had known of the situation for some years”.

CAA surveillance staff had had strong signals for nearly four years leading up to the accident that the Training Manager was likely to have had little involvement with the training and checking of the operator’s pilots.

It should be remembered the operator’s Training Manager was working as an NZ CAA accepted post-holder in another NZ CAA approved operator.

The CAA staff had known the extent of the Training Supervisor’s internal training, and very likely had known that the operator had no approval for this.

Some CAA surveillance staff admitted that there had been some uncertainty with interpreting the rules but, in their view, the Training Supervisor had raised the operator’s standards. Nevertheless, an avoidable safety risk existed because the operator’s training system, including the use of internal instructors, had not been formally assessed and approved by the CAA.

Internal CAA processes had not ensured that higher-level CAA managers were made fully aware of the true situation.

The CAA cannot reasonably be expected to ensure total compliance by all participants in the sector. However…in this case the CAA had had good cause and ample opportunities to intervene at an early stage.

TAIC’s Five Key Safety Lessons From This Accident

- Aircraft operators’ senior management have a regulatory duty to maintain proper and effective oversight of their operations. Doing otherwise will compromise the safety of the operations and increase the risk of repeat accidents.

- Proper training of pilots is critical to the safety of air operations. Any training and competency system must ensure that pilots are trained and experienced to levels appropriate for their roles and responsibilities.

- Every operator must provide adequate supervision of its pilots, appropriate to the pilots’ experience and training and the nature of the operations.

- Aircraft manufacturers set ‘never exceed’ limitations for good reasons. Pilots should not, under any circumstances, load or operate their aircraft outside the limitations.

- With knowledge comes responsibility. If a senior person working for an air operator or an inspector working for the regulator identifies a serious safety issue with an operation, the issue should be formally raised and action taken to address it.

TAIC Safety Recommendations

On 21 February 2019 the Commission recommended that the Director of Civil Aviation initiate an independent review of CAA surveillance reports and any findings raised for Part 135 operators since 2014 to measure the effectiveness of the surveillance policies and procedures that the CAA has put in place, including the effectiveness of their implementation. If the independent review finds unidentified or unresolved safety issues with specific operators, it is recommended that the Director of Civil Aviation take the appropriate urgent action to resolve those issues. (002/19)

Safety Actions

NZ CAA responded:

PriceWaterhouseCoopers (PwC) was appointed to undertake the independent review, which will sample 200 inspection activities conducted over the period 1 January 2014 to 1 December 2018.

PwC also helped facilitate the NZ CAA’s Sector Risk Profile of Part 135 Helicopter and Small Aeroplane Operations (updated May 2019).

NZ CAA only accept, according to a press release, that their oversightshort comings were primarily only in 2011-2012. However they concede that:

…a small number of operators that initially raised concerns during the PwC review had been removed from the aviation system by the CAA or been subject to other effective interventions that had reduced the risk they posed.

They also claim the operator in this accident “was not at all typical of the vast majority of other operators in the sector” but don’t explain why that atypicality was not recognised and acted upon. The Chair of the CAA Board contends that “by November 2015, the CAA had already made significant improvements to how it conducted its oversight of the aviation industry.”

Meanwhile:

Three weeks after the accident, senior pilots from the different operators at Fox Glacier agreed to advise each other when they thought marginal weather conditions existed and that they would treat any such assessment as though it were made by one of their own senior pilots.

UPDATE 23 June 2019: ‘Secrecy and cover-up’: Explosive allegations from within the Civil Aviation Authority

The CAA informant who spoke to Newshub has worked at the agency for several years. By his own admission, he was taking a big risk going public – but decided to on behalf of his colleagues and in the interests of Kiwi travellers. He says the issues largely concern the behaviour of managers, especially those in the Helicopter and Health and Safety units. Managers are prone to sweeping complaints under the carpet, the whistleblower claims. “It’s a culture of secrecy and cover-up.”

Internal documents obtained by Newshub suggest some staff want to complain about issues but won’t because they “don’t trust the process” and have concerns about “incompetent managers”. But the CAA’s Director Graeme Harris has responded by saying it has “very robust” processes to deal with poor performance and complaints.

UPDATE 24 June 2019: Exclusive: Leaked report reveals major overhaul for Civil Aviation Authority

UPDATE 1 August 2019: NZCAA and pilots’ association meet for crunch safety talks after high-profile helicopter crashes

Background and Leaving Helicopters Unattended Rotors Running

This video (uploaded 13 January 2018) shows a Fox Glacier tour flight in better weather:

https://youtu.be/C_UAHtR6KhY

Note the passengers board an empty rotors running helicopter before the pilot.

TAIC reported on the collision of The Helicopter Line AS350B2 ZK-IMJ with parked helicopter ZK-HAE, near Mount Tyndall, Otago on 28 October 2013 (mentioned above). In that report TAIC comment:

Although not a factor in this accident, a further safety issue identified during the inquiry was the widespread practice of allowing passengers to leave and return to helicopters parked on snow while the rotors are turning. Frequently the pilot will also disembark to guide the passengers while they move under the main rotor disc. There is a serious risk to people on the ground if a helicopter has settled into fresh snow or it breaks through an apparently hard surface crust. Should this happen the clearance between the rotor disc and people walking beneath could reduce sufficiently for someone to be struck by the rotor blades.

The Director of Civil Aviation informed the Commission of proposed Civil Aviation Rules [new rules 91.120 and 135.67 proposed in a NPRM in February 2017] that, if passed, could address the hazard of leaving helicopters unattended with the rotors turning under power. However, there is no certainty that the proposed rules will be implemented.

Therefore, the Commission recommended that the Director of Civil Aviation ensure that helicopter operators that conduct snow landings address in their safety management systems the hazard of passenger disembarkation and embarkation during those landings while the rotors are turning.

At the time of writing in June 2019 neither Part 91 or Part 135 have been changed. Its not clear how the hazard is addressed by the operators’ SMSs, noting also the risk of sudden gusts or slackening collective friction.

Safety Resources

- Wayward Window: Fatal Loss of a Fire-Fighting Helicopter in NZ

- All Aboard CFIT: Alaskan Sightseeing Fatal Flight A Controlled Flight Into Terrain (CFIT) accident in Alaska provides a case study of a pathological safety culture, with management and peer pressure, compounded by poorly thought out contracting and scheduling by a cruise line which meant aircraft were making high risk flights in poor weather.

- NTSB Reveal Lax Maintenance Standards in Honolulu Air Tour Helicopter Accident The NTSB reveal shocking maintenance standards prior to an air tour accident in which a 16 year old boy died and his parents were seriously injured.

- Survey Aircraft Fatal Accident: Fatigue, Fuel Mismanagement and Prior Concerns Concerns had been raised about the pilot and the operation just days before this fatal accident. It highlights the importance of doing a proper due diligence and having independent aviation expertise available when contracting aircraft.

- US Fatal Night HEMS Accident: Self-Induced Pressure & Inadequate Oversight Four died when Metro Aviation AS350B2 N911GF suffered a loss of control due to spatial disorientation after taking off into night instrument meteorological conditions from a remote site.

- Italian HEMS AW139 Inadvertent IMC Accident We look at the ANSV report on a HEMS helicopter Inadvertent IMC event that ended with an AW139 colliding with a mountain in poor visibility.

- Culture + Non Compliance + Mechanical Failures = DC3 Accident TSB raise issues with the TC approach to regulation

- Operator & FAA Shortcomings in Alaskan B1900 Accident NTSB raise issues with the FAA approach to regulation

- Canadian KA100 Fuel Exhaustion Accident This accident highlights important human factors, competence and regulatory oversight issues.

- How a Cultural Norm Lead to a Fatal C208B Icing Accident TSB explain how an airline risk assessed ops into icing, had not implemented the mitigations but had started flying into forecast icing with fatal consequences.

- Performance Based Regulation and Detecting the Pathogens Devastating rail accidents in the US and Canada highlight the challenges for regulators introducing Safety Management System rules and/or PBR.

- UPDATE 5 April 2020: HEMS AW109S Collided With Radio Mast During Night Flight

- UPDATE 13 September 2020: Hawaiian Air Tour EC130T2 Hard Landing after Power Loss (Part 1)

- UPDATE 18 October 2020: Hawaiian Air Tour EC130T2 Hard Landing after Power Loss (Part 2 – Survivability)

- UPDATE 17 January 2021: Grand Canyon Air Tour Tragic Tailwind Landing Accident

Recent Comments