Unalaska Saab 2000 Fatal Runway Excursion: PenAir N686PA 17 Oct 2019

The US National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) has issued an investigative update for the 17 October 2019 runway overrun of PenAir Saab 2000 N686PA (Flight 3296) while landing at Tom Madsen Airport (PADU/DUT), Unalaska, Alaska (Port of Dutch Harbor). This was only the second fatal accident involving a US Part 121 passenger airline since 2009.

The flight was cleared for the RNAV runway 13 approach into PADU.

The aircraft passed through the airport perimeter fence, crossed a road, struck a sign and came to rest on shoreline rocks. Two propeller blades entered the fuselage.

Of the 42 persons on board, one passenger was fatally injured and several others sustained injuries.

NTSB Safety Investigation

The NTSB say that:

According to the flight crew, the captain was the flying pilot and the first officer was the pilot monitoring. The first officer stated that he completed the performance calculations during cruise, before beginning descent, and prior to obtaining the weather at DUT. The flight crew indicated that they conducted a go-around during the first approach to runway 13 because they were not stabilized. On the second approach, the flight crew indicated they touched down about 1,000 feet down the runway and the captain initiated reverse thrust and normal wheel-braking. The captain stated that he went to maximum braking around the “80 knot call.” The flight crew reported that they attempted to steer the airplane to the right at the end of the runway to avoid going into the water.

The NTSB’s initial feedback from study of the Cockpit Voice Recorder (CVR) was that:

Weather was initially reported (by the local weather observer) as winds 210 degrees at 8 knots, gusting to 14 knots, visibility 7 to 10 miles, a ceiling at 4,300ft that was broken, a temperature of 8 degrees Celsius, a dew point of 1 degree Celsius, and an altimeter setting of 29.50 inches Hg. A later transmission from the local weather observer to another aircraft reported the winds were 180 degrees at 7 knots, visibility 8 to 10 miles with showers in the vicinity, and a broken ceiling at 3,900 feet.

The aircraft was configured for the approach: flaps 20, gear down. During the approach, the winds were reported as 270 deg at 10 knots. A go-around was executed, and the flight returned for a visual approach to runway 13. During the go-around, the winds were reported as 300 degrees at 8 knots. After the go-around, the winds were reported to be 290 at 16 gust 30 (multiple overlapping radio transmissions occurred at this time). Transmissions between the weather observer and another airplane indicated that winds favored runway 31 but could shift back to runway 13.

The aircraft was configured again for the approach: flaps 20, gear down. During the second approach, winds were reported as 300 degrees at 24 knots. The aircraft touched down and the roll out lasted approximately 26 seconds until the aircraft departed the runway.

The crew announced, over the PA, an evacuation out the right side of the aircraft and made a radio call for assistance.

Press reports indicate that only one emergency exit was opened.

The Flight Data Recorder (FDR) was examined:

Touchdown occurred with the aircraft travelling at about 129 knots indicated airspeed and 142 knots ground speed. Following touchdown, the aircraft decelerated reaching a peak deceleration of -0.48 g., with the engines operating in reverse mode. About 25 seconds after main gear touchdown, a change in aircraft pitch and roll, and an increase in the magnitude of triaxial acceleration forces was recorded, consistent with the aircraft departing the runway surface. The engines were taken out of reverse mode and ground speed at that time was about 23 knots.

NTSB note that:

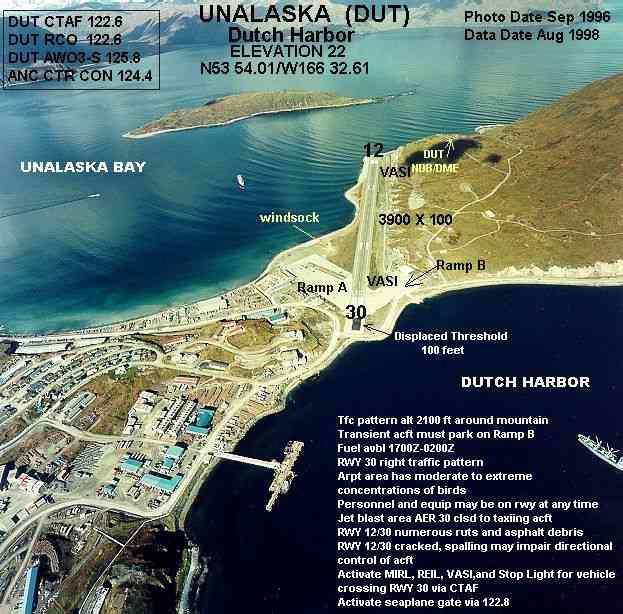

Runway 13/31 at PADU is 4,500 feet long and 100 feet wide with a grooved asphalt surface.

There was a 5-inch-wide dark rubber witness mark on the runway, about 15 feet left of the runway centerline, starting about 1,840 feet from runway 13’s displaced threshold, and extending about 200 feet. The left main landing gear outboard tire was found deflated with an area that had worn entirely through the tire.

Witness marks indicated that the airplane departed the runway and overrun area, traversed a section of grass, impacted a 3- to 4-ft high chain-linked perimeter fence with evidence of left engine propeller contact, crossed a ditch, impacted a large rock, and crossed a public roadway. The left wing or left engine propeller struck a 4 to 5 ft vertical signal post on the opposite shoulder of the road and the left propeller struck a 6 to 8-ft high yellow diamond shaped road sign. There were strike marks consistent with the right engine’s propeller tips contacting the ground near where the airplane came to rest.

Examination revealed a hole and significant impact damage to the left forward fuselage around the 5th window.

A propeller blade was loosely stuck in the surrounding structure external to the fuselage and another propeller blade was found inside the fuselage.

All cabin seats (15 rows) were intact and secure to the floor except for seat 4A, which was displaced and damaged. The damaged area of the cabin was contained within the area on the left side between fuselage station (FS) 399 (seat 3A) and FS 488 (seat 6A), with extensive damage evident at FS 435.

Part of the overhead compartment was hanging down or separated and the seat 4A window fuselage frame was found on the cabin floor.

The Saab 2000 is powered by two Rolls-Royce AE2001A turboprops fitted with Dowty R381/6-123-F/5 propellers (each with 6 composite blades).

The left engine remained attached to the engine mounts although the right rear engine mount was bent and buckled. The left engine’s propeller assembly was sagging in relation to the engine’s nacelle with the propeller shaft support resting on the forward part of the nacelle. The propeller reduction gear box front housing was fractured 360° around forward of the diaphragm and in the area of the ring gear. There were broken pieces of gear box housing laying on the engine deck. The propeller shaft aft bearing was missing 3 adjacent rollers from the bearing cage. The engine was complete and did not have any indications of an uncontainment or case rupture.

The left propeller hub was intact. Pieces of the blade, either part of the airfoil or just the blade butt, remained in all six blade locations on the hub. All of the propeller blades that still had parts of an airfoil remaining were in the feathered position. At those locations were the airfoil was missing, the blade retaining clamps were in place with the retaining bolts in place and safety wired. Blades Nos. 1, 3 and 4 were missing, although the base of each blade remained in the hub. Blade No. 2 was in place in the hub and the blade was fractured transversely across the airfoil about 28.5-inches from the disk to the fractured end. Blade No. 5 was broken about 48-inches from the disk to the fractured end. Blade No. 6 was broken about 48-inches from the disk to the fractured end.

The three missing blades were all recovered.

There was a propeller blade that was recovered from the water that was about 48-inches long. There was a propeller blade that was found hanging on the left side of the airplane from some cabin insulation that had wrapped around the butt of the blade that was about 58.5-inches long. There was a blade that was found in the cabin that was about 57-inches long.

The wreckage was lifted by crane barge on 19 October 2019.

Both crew held ATPLs but were low time on type.

The captain…had accumulated about 20,000 total flight hours of which about 14,000 hours were in the DH-8 and 101 hours were in the Saab 2000. The first officer…had accumulated 1,446 total flight hours of which 147 were in the Saab 2000.

PenAir…had a “captains only” rule for takeoffs and landings and a 300-hour minimum in-aircraft as PIC requirement. According to former and current PenAir pilots, this has changed under the new ownership. A page dated April 25, 2019, from the PenAir Operations Manual, states that the 300-hour PIC minimum may be waived if a company check airman who has flown with the pilot provides a letter of recommendation and the Chief Pilot approves the exception.

PenAir had previously gone through bankruptcy and was sold in October 2018. It is now majority-owned by the same Manhattan-based private equity firm, JF Leman, that owns Ravn Air Group, an operator which has come under scrutiny for safety issues previously. PenAir has stop operating the S2000 to Unalaska and Ravn has instead resumed flights with a Dash 8. Codeshare partner Alaska Airlines has cancelled all reservations to and from Unalaska through to 31 May 2020.

Video of a SF340 landing at Unalaska

UPDATE 6 April 2020: Ravn enters Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection and suspends operations during the COVID-19 crisis.

UPDATE 17 October 2020: The NTSB have issued no further investigative update.

UPDATE 22 October 2020: One year later: The crash of Flight 3296. This Anchorage Daily News opinion piece by Colleen Mondor claims the airline Chief Pilot was replaced 1 month after the accident. It also reports:

Flight 3296′s weight and balance has not been released, it is possible to determine a conservative estimate of its total weight from available data. According to the manufacturer, the aircraft has a basic empty weight of about 30,500 pounds (this includes the three-member crew). Adding fuel for required reserves and Cold Bay as an alternate destination (about 2,000 pounds) and weight for 39 passengers at the FAA standard for summer adults (195 lbs x 39 = 7,605 pounds), a total weight of 40,105 pounds can be calculated. This excludes any baggage that may have been onboard.

For Runway 13 at Dutch Harbor, PenAir’s company performance standards permitted a landing weight, with 20 degrees of flaps, of 40,628 pounds with zero wind, 35,402 pounds for 5 knots of tailwind and 29,955 pounds for 10 knots of tailwind. It recommended a reduction of 1,031 pounds for each additional knot of tailwind.

At the time of the second approach the NTSB report a 24 knot tailwind.

There is thus no discernible calculation that would recommend landing on Runway 13 with the reported winds at the time of the crash at the aircraft’s approximate weight.

“A passenger asked the captain why he landed,” explained [a passenger] in an email, “and he calmly said the computer showed he was within the safety margin.” There is no onboard computer that calculates landing performance…the PIC could only have been referring to an app likely used on his company-issued iPad [Electronic flight bag]. When asked if PenAir had authorization to utilize performance calculation software, the FAA referred the question, as part of an ongoing investigation, to the NTSB.

Soon after the accident…Alaska Airlines dropped the lucrative Capacity Passenger Agreement (CPA) it had with Ravn. The loss of the CPA, which paid Ravn for the Unalaska flights at “predetermined rates plus a negotiated margin, regardless of the number of passengers on board or the revenue collected,” had serious financial ramifications for the company.

UPDATE 16 December 2020: The NTSB open the public docket.

Public Docket: Pilot Experience

NTSB comment that:

The PenAir 300-hour minimum to qualify for company designated airports was intended as a time in type and time in left seat with company prior to beginning company designated airport training.

The VP of flight operations at Ravn said that while there must have been reasons why 300 hour minimum was put in place in the first place, it wasn’t consistent with how 121 carriers flew in the continental U.S. “I’m not convinced that it’s necessary because it’s not done elsewhere. There are mountains around the country, around the world. Air is air. Physics are physics. Why is this different?”

The chief pilot at PenAir said that the idea to reduce requirements came from the VP of flight operations at Ravn… The chief pilot at the time of the accident was asked about concerns pilots had to reducing the company designated airport experience requirement. She stated that several pilots voiced concerns, but she didn’t ask them why, stating “I just assumed it was because they thought Dutch Harbor was an airport, a special airport.” Others did not bring up concerns because they felt that their concerns would not be heard if they had and that the decision reduce the qualification requirements had already been made without line pilot input. When asked why he did not voice his concerns to management, one pilot said that it appeared as if management viewed senior crew members at as a threat. He felt, as a senior crewmember, his job wasn’t in jeopardy but he “didn’t want to make any waves.” He further stated the proposed change in company designated airport qualifications was a “big factor” for his resignation as check airman.

Public Docket: Safety Culture in PernAir After Purchase by Ravn

Ravn’s safety director told the NTSB the overall safety culture as “still good,” but admitted that there was “more openness, definitely, with the prior PenAir management” reporting had gone down and pilots had come to him and said they were “not as comfortable anymore” freely raising concerns.

Several pilots said that the safety culture at PenAir was good, “They’ve always followed up on everything that I know of” and “take it very seriously.” Others said they were “not impressed at all” with the safety culture, of which one pilot rated the culture a level 3 on a scale from 1 to 10 at the time of the accident.

Many pilots stated that pilot morale had begun to decline after the bankruptcy, in the summer of 2019 with the conversations of reducing special airport qualification minimums, and further after the recently upgraded captain was “counseled” in August by the chief pilot and VP of flight operations. The director of safety stated that he considered the overall safety culture as “still good” but said that he had pilots approach him saying they were “not as comfortable anymore… saying something or making a decision and being questioned on it” since the new management came in.

NTSB also highlight a prior event that seems to have had a chilling effect:

After having a concern about management response to a flight decision, one pilot opted not to submit a safety report stating that despite anonymous reporting, the chief pilot of PenAir and VP of flight operations of Ravn would know she submitted it, stating “ I was afraid of how that was going to affect my job here.”

Several [pilots] interviewed [by NTSB] relayed an instance where a new captain was questioned for refusing a flight near weather minimums. This captain described the situation where she was approached by the Pen Air chief pilot and Ravn VP of flight operations after refusing to the flight. She stated that “my crew and I don’t really feel comfortable … showing up at work at 6:00 a.m., being here for 6 hours already [on ‘gate hold’] and going out to Dillingham and doing a non-precision approach down to minimums and probably going missed off of it, quite frankly, with where the weather was at.” After returning to the base, the chief pilot and VP of flight operations “counseled” her on her decision.

She said that “they didn’t understand what was unsafe about it. [The VP of flight operations] told me that it was unprofessional and immature and that I didn’t get to have my own set of standards. He told me if I had a legal airplane, legal weather and legal crew, then it was my job to go. He said that the only thing I should be worried about was what the forecast visibility was, because that was the only thing that was legally binding.” She said he further stated that if she made a decision like this again, “he didn’t trust my decision-making in the left seat, and he didn’t think I deserved to be on the flight line anymore.”

When asked about the situation during investigation interviews, the chief pilot stated that the captain’s job was never in jeopardy and the issue was that a “young and inexperienced” captain had “walked off the job.” When the VP of flight operations was asked if the captain’s job was in jeopardy after this event, he said that it depended on if she changed her behavior and showed maturity, “if she’s not able to show the maturity level… in your job, then, yeah, of course, your job is in jeopardy.”

There were several senior pilots who were concerned about the management’s response to the captain’s situation. One pilot said the newer pilots refer to senior pilots for guidance and he decided to talk to the chief pilot about it considering the possibility that new management didn’t understand the nuances of the weather like senior pilots who encountered it consistently. When the senior pilot voiced his concern with the chief pilot and suggested the chief pilot talk with the VP of flight operations about safety culture, “[the chief pilot] made it real clear that I’d better get my facts straight before I go talking to [the VP of flight operations].” The director of safety said that he had heard several reports regarding pilots getting reprimanded by the VP of flight operations at Ravn and reached out to the PenAir president. He relayed that the president spoke with the VP of flight operations and told the VP of flight operations that they need to maintain their just culture.

The accident captain also described an encounter about 2 years prior with in his role as director of training at Ravn where a pilot confided in him that they felt they would be “called on the carpet” by the VP of flight operations for reporting a safety issue. The accident captain approached the CEO of the company for a resolution, however the VP of flight operations “got a little upset because I went directly to [the CEO]” and told the accident pilot that “a heads up would have been nice.”

Landing Gear Speed Transducer Wiring Error

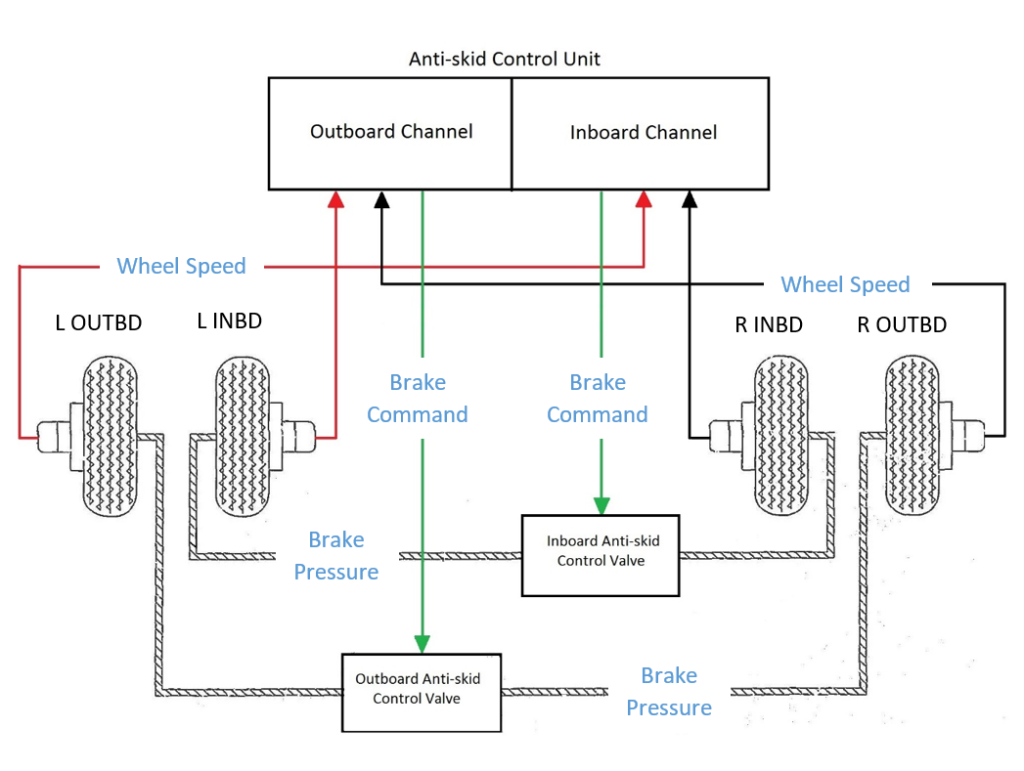

Investigators found the left Main Landing Gear wheel speed transducer wire harnesses were incorrectly installed. The cross wiring is shown below in red:

The manufacturer of the anti-skid system, Crane, was asked about the system response to a scenario of crossed left main gear wheel speed sensor wiring and the left outboard tire entering a skid condition.

According to Crane the following would be expected:

1. As long as the left outboard tire is in a deep skid, the inboard circuit would sense the skid and quickly reduce brake pressure to the inboard wheels to near zero.

2. The right outboard wheel would still have skid protection, except it would be compared to the left inboard wheel.

3. Some skid protection for the left outboard could occur if the right outboard tire started to skid. The outboard circuit would sense the skid and reduce brake pressure to the outboard wheels.

UPDATE 7 October 2021: The NTSB will hold a public hearing on 2 November 2021.

UPDATE 2 November 2021: NTSB release CCTV of runway excursion.

NTSB Probable Cause

The the probable cause of this accident was the landing gear manufacturer’s incorrect wiring of the wheel speed transducer harnesses on the left MLG during overhaul. The incorrect wiring caused the antiskid system not to function as intended, resulting in the failure of the left outboard tire and a significant loss of the airplane’s braking ability, which led to the runway overrun.Contributing to the accident were (1) Saab’s design of the wheel speed transducer wire harnesses, which did not consider and protect against human error during maintenance; (2) the FAA’s lack of consideration of the RSA dimensions at DUT during the authorization process that allowed the Saab 2000 to operate at the airport; and (3) the flight crewmembers’ inappropriate decision, due to their plan continuation bias, to land on a runway with a reported tailwind that exceeded the airplane manufacturer’s limit.

The safety margin was further reduced because of PenAir’s failure to correctly apply its company-designated PIC airport qualification policy, which allowed the accident captain to operate at one of the most challenging airports in PenAir’s route system with limited experience at the airport and in the Saab 2000.

NTSB Safety Recommendations

As a result of this investigation, we recommended that the FAA and the European Union Aviation Safety Agency review system safety assessments for landing gear systems on currently certificated transport-category airplanes to determine whether the assessments evaluated and mitigated human error that could lead to cross-wiring of antiskid brake system components, including the wheel speed transducers, and then require transport-category airplane manufacturers without such assessments to implement mitigations.

We also recommended that the FAA and the European Union Aviation Safety Agency require system safety assessments addressing the landing gear antiskid system for the certification of future transport-category airplane designs; the certification should ensure that the system safety assessments evaluate and mitigate the potential for human error that can lead to a cross-wiring error.

Further, we recommended that Saab redesign the wheel speed transducer wire harnesses for the Saab 2000 to prevent the harnesses from being installed incorrectly during maintenance and overhaul and that the FAA and the European Union Aviation Safety Agency require organizations that design, manufacture, and maintain aircraft to establish a safety management system.

We also recommended that the FAA notify certificate management team personnel about the circumstances of this accident and emphasize the importance of detecting and mitigating the safety risks that can result when certificate holders experience significant organizational change, such as bankruptcy, acquisition, and merger, all of which PenAir was experiencing for more than 2 years before the accident. We further recommended that the FAA revise agency guidance to include a formalized transition procedure to be used during a changeover of certificate management team personnel responsible for overseeing a certificate holder that is undergoing significant organizational change to ensure that incoming personnel are fully aware of potential safety risks.

In addition, we recommended that the FAA include the runway design code for runways of intended use among the criteria assessed when authorizing a scheduled air carrier to operate its airplanes on a regular basis at an airport certificated under Title 14 Code of Federal Regulations Part 139.

UPDATE 28 November 2021: Swedish and UK investigators dispute US conclusions on fatal PenAir Saab overrun

Other Safety Resources

- Operator & FAA Shortcomings in Alaskan B1900 Accident – we looked at several Ravn Group accidents

- Alaska B1900C Accident – Contributory ATC Errors

- All Aboard CFIT: Alaskan Sightseeing Fatal Flight

- Alaskan Mid Air Collision at Non-Tower Controlled Airfield

- UPDATE 5 March 2020: S2000 Runway Excursion at the Start of the Take Off Roll

- UPDATE 9 December 2020: A Saab 2000 Descended 900 ft Too Low on Approach to Billund

- UPDATE 16 May 2021: Cessna 208B Collides with C172 after Distraction

Recent Comments