Airbus EC135P2+ Air Ambulance CFIT when Pilot Distracted Correcting Tech Log Errors (Med-Trans / LifeForce 6 N558MT, North Carolina)

On 9 March 2023 LifeForce Airbus EC135P2+ air ambulance N558MT, operated by Med-Trans, suffered a Controlled Fight into Terrain (CFIT) during a night time patient transfer near Franklin, North Carolina. The helicopter stuck trees atop high ground an force landed on to a road. Three of the occupants received minor injuries and the fourth escaped uninjured.

Wreckage of Med-Trans / LifeForce 6 Airbus EC135P2+ Air Ambulance N558MT After Forced Landing Following Mountain CFIT (Credit: FAA via NTSB)

The US National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) safety investigation report was published 6 June 2023.

The Accident Flight

The helicopter was based as Western Carolina Airport, Andrews, North Carolina. The pilot was working a 06:30 to 18:30 shift. The 51 year old pilot had 4723 flying hours of experience, 1867 on type according to the accident report form. We suspect this may be just civil time as the pilot is a former USMC squadron commander.

At c17:50 a request was received for a patient transfer between two hospitals. This would have been the pilots fourth tasking of the day, but the pilot stated to the NTSB “we felt confident we could complete the flight within the 14-hr window” (presumably the applicable duty time limit).

At 18:13 they arrived at Erlanger Western Carolina Hospital, Murphy, North Carolina to collect the patient. The pilot stated that while the patient was prepared for flight there was one distraction for the pilot, a call with the Regional Area Manager (RAM):

I was instructed to double check maintenance due times to ensure we would not overfly any inspections due to a temporary glitch between RAMCO (company maintenance program) and FlightLog that was being rectified.

Subsequently:

I computed and recorded the weight & balance information in the flight log for the upcoming leg and attached the NVG [Night Vision Goggles] battery pack and mount to my helmet in anticipation of donning the goggles during the next leg…

There is no indication that the NVGs were tested.

The flight was forecast as 38 minutes and twilight was at c19:19.

Weather was workable: reporting and forecasting VFR along the route. The majority of the reports…indicated 10SM, -RA, BKN 060 30.14.

The pilot commented to NTSB that the highest obstacle en route was 6,100 ft with several 5,000 to 5,500 ft peaks too. The helicopter departed shortly after 18:45.

Upon reaching Vy (65kts) I selected IAS (indicated airspeed) mode on the autopilot and HDG (heading) mode to take us just north of the Tusquitte Spine (an east west running ridge..).

At c18:50:

I dialled in 5500’ and shifted to V/S (vertical speed) mode with AltA (Altitude Acquire).

Upon reaching that altitude airspeed increased to ~110 KIAS (~132 Kts ground speed.)

Although, the pilot was intending to don NVGs they were not mounted on the pilot’s helmet ready to flip down. They were in fact “resting on the logbook” (i.e. Technical Log) on the empty front seat.

I was just about to remove the caps and don them when I chose instead to relocate the logbook to the pilot door compartment where we typically stow it during flight. With logbook in hand, I decided to double check the printed-out RAMCO due values against the logbook values since we had already flown over four hours that day with an additional 1.3-1.5 coming up for this flight.

The pilot did not comment on whether his attention on the logbook was due to a loss of faith in the accuracy of the aircraft technical records or because impending maintenance was close.

At 18:55 the pilot descended to 5000′ (again by an AltA input) due to some wisps of cloud below the cloud floor. While still operating VFR the pilots stated…

I went back heads down and saw that engine #1 hours had a transcription error that I traced back a few pages. I made the pen-and-ink changes at which point the flight nurse asked for an updated ETE (estimated time en route).

Coming back heads up, I saw that we were rapidly approaching the tree covered peak of a mountain. There was no doubt in my mind that impact was imminent. I hauled back on the cyclic to affect a max rate climb. Nearly simultaneously, the undercarriage of the aircraft and tail boom struck several trees with the sound and force expected when those two objects collide at 132 kts.

He aircraft continued to climb but airspeed dropped below 70kts and…

…the nose tucked to the right and the aircraft began to spin. It was clear what was happening so I tried to follow the nose with the cyclic in an attempt to execute an expanding spiral and achieve weather vaning into controlled flight…with a 500-1000 ft/min ROD (rate of descent).

We saw a valley with a few farmer’s fields off the nose…. The flight medic called out that he had a good field to the three o’clock which we chose to attempt. Altitude was estimated at ~300’AGL, airspeed of 100-110kts with the nose still out 25+ degrees to the right.

I figured with a hard right turn while simultaneously dumping the collective to unload the head would result in an appropriate line up assuming the roll-out was timed well. I bled off too much airspeed during the 180 degree turn and the aircraft began to spin. Noticing the two-lane hard ball road briefly, I attempted to direct the aircraft there to execute a cut-gun autorotation.

The aircraft impacted trees while descending vertically.

The fenestron impacted the bank on the east side of the road and the skids spread.

Wreckage of Med-Trans / LifeForce 6 Airbus EC135P2+ Air Ambulance N558MT After Forced Landing Following Mountain CFIT (Credit: FAA via NTSB)

Both sliding doors were jammed, but the windows had blown out as had some of the cockpit plexiglass. The medic announced he was going for help and climbed out the #1 side window frame.

A medical monitoring device had broke free and landed on the patient’s chest. The NTSB do not examine this survivability matter.

The pilot…

…noticed jet fuel on the south side of the aircraft spreading across the road and decided to turn off the aircraft battery figuring darkness was better than fire.

The medic flagged down a passing car and asked for the driver to call the emergency services.

The pilot the went on to add that “this incident was in no way caused by perceived pressure to fly” or “caused by lack of training” and “there is not a ‘cowboy culture’ or ‘maverick attitude’ in Med-Trans.

He added that as a former USMC “Aviation Safety Officer and mishap investigator” he understood “culpability” (which is of course just another term for blame), that “that it was my actions and my inactions, that caused this incident” and that “the system did not fail me, I failed the system”.

No safety actions are reported.

NTSB Probable Cause EC135P2+ N558MT

The pilot’s improper decision to review an aircraft logbook while en route, which resulted in controlled flight into terrain.

Our Safety Observations

The closing remarks in the pilot’s statement might make some readers suspect they were intended to reduce the chances the NTSB might examine the organisation deeper and wonder if their had been any prior collusion on the statement’s contents or whether it reflected the thrust of initial investigative interviews.

NTSB did delve far deeper after another night time helicopter air ambulance CFIT accident: Survival Flight Fatal Accident: Air Ambulance Operator’s Poor Safety Culture. That investigation resulted in a 2,600 page public docket with extensive interviews within the operator’s management and line personnel.

Med-Trans’ last fatal accident, the loss of Bell 407 N503MT and four lives, was 19 years earlier on 13 July 2003. The NTSB probable cause was: “The pilot’s failure to maintain terrain clearance as a result of fog conditions. A contributing factor was inadequate weather and dispatch information relayed to the pilot”. Two helicopter operators had turned down that tasking and one had abandoned due to fog. The Med-Trans B407 pilot was not told that. In this case an 83 page organisational factors report was prepared by NTSB. There the CEO suggested a rapid expansion in the organisation was coincidental but the Director of Operations noted their training organisation had not grown to cope.

That accident was less than 3 months after their previous fatal accident. On 21 March 2004 B407 N502MT crashed kill 4 of the 5 occupants. The NTSB probable cause was: “The pilot’s inadvertent encounter with adverse weather, which resulted in the pilot failing to maintain terrain clearance. Contributing factors were the dark night conditions, the pilot’s inadequate preflight preparation and planning, and the pressure to complete the mission induced by the pilot as a result of the nature of the EMS mission.”

In the 2023 EC135P2+ case the public docket is 17 pages and the NTSB report is pretty much just cut and paste from that (but with less detail then we managed over a coffee on a Saturday morning!), with no attempt to examine the recorded flight data and without even locating the initial point of impact!

The operator claims to have HTAWS fitted within their fleet and should have as its has been a regulatory requirement for helicopter air ambulances in the US since 24 April 2017 (Part 135.605). NTSB do not consider its performance. The FAA has recently warned about the risks of inhibiting TAWS.

While issuing a final report in 3 months should be a positive, when it adds nothing to the statements received and neither leads to or encourages any safety action, the value is nil.

We do wonder if NTSB investigators are being driven to meet report closure metrics (e.g. number reports open, time to closure etc) rather than to share learning.

Safety Resources

The European Safety Promotion Network Rotorcraft (ESPN-R) has a helicopter safety discussion group on LinkedIn. EASA discussed CFIT & Distraction in 2020.

You may also find these Aerossurance articles of interest:

- Managing Interruptions: HEMS Call-Out During Engine Rinse

- Be Careful If You Step Outside!: Unoccupied Rotors Running AS350 Takes Off

- AS350B3 Rolls Over: Pilot Caught Out By Engine Control Differences

- AS350B3 Dynamic Rollover When Headset Cord Snags Unguarded Collective

- Fatal B206L3 Cell Phone Discount Distracted CFIT

- Cessna 208B Collides with C172 after Distraction

- Air Ambulance Helicopter Downed by Fencing FOD

- Ambulance / Air Ambulance Collision

- Maintenance Misdiagnosis Precursor to EC135T2 Tail Rotor Control Failure

- Misassembled Anti-Torque Pedals Cause EC135 Accident

- AAIB Report on Glasgow Police EC135 Clutha Helicopter Accident

- EC135P2+ Loss of NR Control During N2 Adjustment Flight

- Austrian Police EC135P2+ Impacted Glassy Lake

- Oil & Gas Aerial Survey Aircraft Collided with Communications Tower

- Survival Flight Fatal Accident: Air Ambulance Operator’s Poor Safety Culture

- US Fatal Night HEMS Accident: Self-Induced Pressure & Inadequate Oversight

- That Others May Live – Inadvertent IMC & The Value of Flight Data Monitoring

- Air Ambulance Helicopter Struck Ground During Go-Around after NVIS Inadvertent IMC Entry

- UPDATE 29 July 2023: Missing Cotter Pin Causes Fatal S-61N Accident

- UPDATE 4 February 2024: HEMS Air Ambulance Landing Site Slide

- UPDATE 20 July 2024: Night CHC HEMS BK117 Loss of Control

And:

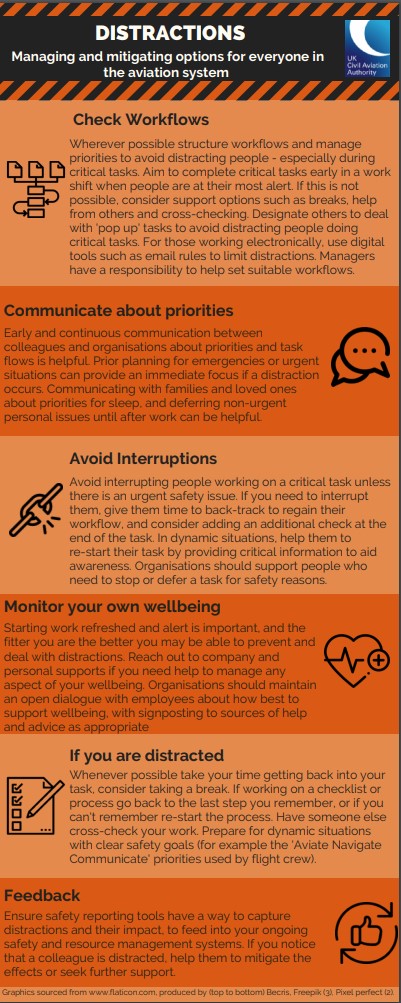

The UK CAA has issued this infographic on distraction:

Also on human factors:

…and our review of The Field Guide to Understanding Human Error by Sidney Dekker presented to the Royal Aeronautical Society (RAeS): The Field Guide to Understanding Human Error – A Review

Recent Comments