AS350B3 LN-OTR Dynamic Rollover When Headset Cord Snags Unguarded Collective

On 12 September 2017 Airbus Helicopters AS350B3 LN-OTR, operated by Helitrans, rolled over onto its side shortly after landing on slightly sloping ground at Laksefjordvidda in the northern district of Finnmark, Norway. All four occupants escaped uninjured.

The helicopter sustained extensive damage but the seats and cabin floor structure were intact.

The Accident Flight

The Accident Investigation Board Norway (AIBN) investigation report (issued 12 May 2020 in Norwegian only), explains that the helicopter was chartered to support hunting inspections by three government agencies. This involved first searching to find hunters and then landing to check their weapons and licenses.

The aircraft deployed from its base at Alta at 0800 and made the 1 hour 50 minute flight to the village of Skiippagurra with the pilot and a ‘task specialist’ / ‘loader’ on board. On arrival detail planning commenced with the customer’s inspectors. Due to the nature of the task, the pilot was only told in advance the general area to be searched. The search area could be adjusted if necessary so the flight could be conducted under Visual Flight Rules (VFR).

Initially, the client had announced that two inspectors should be on the flight. This was changed to allow three people to participate and the pilot therefore carried out a new weight and balance calculation. Before departure, the helicopter’s fuel tanks were filled completely. The commander’s calculation showed that the total weight was well within the maximum allowable weight of the helicopter.

It was decided the loader would not join the flight, though the logic for this decision is not discussed in the report.

The controls on the left side of the cockpit were therefore dismantled. One passenger was seated in the front left seat and the other two passengers were seated in the back of the cabin. The pilot flew the helicopter from the front right seat. Before departure, the pilot briefed the passengers on how the helicopter’s doors could be opened and closed, as well as how the seat belts worked. After the passengers were taken on board and the pilot carried out an external inspection of the helicopter, the helicopter’s engine was started and at. In 1125, they took off to begin the task.

All four wore headsets. Helmets were not usual for this type of tasking say AIBN.

While south west of the village some All Terrain Vehicle (ATV) tracks were spotted, which the inspectors took some photographs of. The pilot tried to fly to a particular hunting cabin that the inspectors wanted to fly over, but that was curtailed due to fog so they headed to the west of the village.

Shortly thereafter, they spotted some people, tents and three ATVs [34 km west of the village]. It was decided that the helicopter should land so that the inspectors could carry out a check.

The pilot found a suitable landing site on gently sloping terrain covered with heather. As the hunters had lit a fire its smoke gave a clear indication of the wind direction.

The helicopter landed into wind and sat softly against a slightly sloping surface, from right to left in the direction of travel of the helicopter. The right skid consequently touched the ground first and after the collective lever was further reduced, the left skid also came into contact with the ground.

The pilot explained that the helicopter was steady after landing and that everything felt normal at this time.

To be “absolutely sure” that the helicopter was stable, the pilot would habitually check the condition of the ground before shutting down the engine. He opened the right hand cockpit door to check the ground under the right hand skid. As he lowered his head to the right, he felt like the cord of his headset tighten. The cord was most likely snagged on the collective. The helicopter lifted slightly and started to move to the left. The pilot tries to counter that movement but the aircraft then moved the the right, the right had skid touched the sloping ground and the helicopter rolled over. The pilot quickly shut down the engine.

Everyone on board was properly strapped into the seat belts. The pilot turned and saw that the two passengers in the back of the cabin were hanging in their belts. One passenger noted that it smelled of fuel and all four on board feared the fuel could ignite. Passengers in the cabin loosened the seat belts, opened the left passenger door and quickly egressed. The passenger in the front left seat was unable to open the seat belt. The pilot assisted the passenger by lifting him sufficiently so that he was able to open it. Then the pilot pushed the passenger up so he could evacuate through the front left cockpit door [followed by the pilot].

The helicopter’s emergency signal transmitter (ELT) was not triggered in connection with the accident. There was poor mobile coverage in the area and one of the passengers went up on a ridge nearby and notified the police about the accident from there. At the same time it was informed that everyone on board was unharmed. Police notified the Norwegian National Emergency Rescue Center. A [RNoAF Westland] Sea King rescue helicopter, which was underway on another mission, was diverted and landed at the accident site approx. 45 minutes after the accident happened.

Safety Investigation

AIBN explain that Helitrans proactively conducted an internal investigation “where the focus was on the landing itself and the conditions that could have contributed to the unwanted movement of the cyclic and the collective lever”:

The pilot explained that the flight controls were not locked or secured when he used his right hand to open the door. The company noted that the pilot may have brought with him a habit from the experience of flying the Hughes 500, where the skids can be inspected more easily while the pilots sits in their seat.

The company’s reconstruction in a similar helicopter showed that it was not possible to bend out to the right…without the left hand releasing the collective lever. For moment, therefore, no hands could have been on the

controls… The company explained to that in this individual helicopter the collective lever tended to creep upwards if the friction had not been tightened sufficiently. The pilot had also explained that he preferred a low friction on the collective.The company also considered whether the headset cord could have helped lift the collective lever. The headphones used had straight cord (not a “spiral coil”). In its reconstruction, the company found that it was possible to move an un-tightened collective lever with a cord hooked to it. A spiral cord will not affect the collective lever as much as it will extend when tightened.

AIBN’s Conclusions

The AIBN considers that the landing site, although not prepared in advance, was initially suitable for landing. The helicopter overturned in connection with the pilot checking the condition of the ground before shutting down the engine.

It is likely that the collective lever was not sufficiently secured when the pilot briefly let go and leaned to the right. The Accident Investigation Board has no reason to doubt the pilot’s explanation that the cord on the headset snagged so that the helicopter moved. In addition, the collective may also have crept up as a result of not having sufficient friction.

The pilot’s explanation that he likes to have low friction on the ladder lever may be against recommended practice. The Flight Manual is not very specific, but indicates that there must be sufficient friction to be felt in the control. More friction reduces the possibility that the ladder lever will crawl and it reduces the chance of a cord pulling it. Securing the cord from the headphones and tightening the friction lever friction could thus prevent it from accidentally creeping upwards.

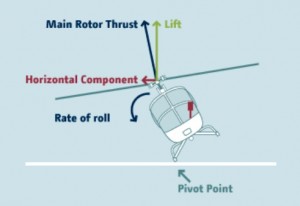

A “dynamic rollover” then occurred.

“Dynamic rollover” can occur during landing or take-off by a helicopter continuing a movement laterally about a point on the ground if available power to control or stop the movement is not present.

The cyclic alone will not be sufficient to stop the movement. The recommended method to prevent dynamic rollover is to lower the collective lever quickly.

The AIBN believes there is safety benefit carrying a task specialist / loader when operating from ad hoc unsurveyed sites.

The Accident Investigation Board will point out that the use of a helmet is generally important in reducing the extent of injury in the event of an accident. In the event of an accident with passengers on board, the likelihood of a faster evacuation of these is increased if the commander is aware and can assist them. In this accident, the passenger in the left seat did not egress on his own and had to get help from the pilot. In other circumstances, such as a fire, this could have been fatal for him if he had not received help in an otherwise survivable accident.

Operator’s Safety Actions

- Remind staff of the importance of guarding flight controls at all times, avoiding loose objects that may interfere with flight controls and use correct friction on the collective and cyclic.

- Evaluate the benefits of having a task specialist / loader on similar taskings.

- Incorporate the lessons from the internal investigation in the next revision of the manuals, procedures and training programme.

Other Safety Resources

EHEST Leaflet HE 1 Safety Considerations discuses static and dynamic rollovers.

You may find these Aerossurance articles of interest:

- Be Careful If You Step Outside!: Unoccupied Rotors Running AS350 Takes Off

- AS350B3 Rolls Over: Pilot Caught Out By Engine Control Differences

- US Police Helicopter Night CFIT: Is Your Journey Really Necessary?

- AS350 Tail Rotor Control Incident, Grand Caymen

- EC130B4 Destroyed After Ice Ingestion – Engine Intake Left Uncovered

- US Fatal Night HEMS Accident: Self-Induced Pressure & Inadequate Oversight

- Firefighting Helicopter Wire Strike

- Wayward Window: Fatal Loss of a Fire-Fighting Helicopter in NZ

- When Habits Kill – Canadian MD500 Accident

- Bear Paws Claw Reindeer Herding Bell 206

- UPDATE 27 December 2020: Fire-Fighting AS350 Hydraulics Accident: Dormant Miswiring

- UPDATE 16 July 2022: Distracted Dynamic Rollover

On error management:

…and our review of The Field Guide to Understanding Human Error by Sidney Dekker presented to the Royal Aeronautical Society (RAeS): The Field Guide to Understanding Human Error – A Review

Recent Comments