Missing Cotter Pin Causes Fatal S-61N Accident (Croman Sikorsky S-61N N615CK, Barking Sands, Hawaii)

On 22 February 2022 Sikorsky S-61N N615CK operated by Croman Corporation was destroyed in an accident at the US Navy Pacific Missile Range Facility (PMRF), Barking Sands, Kauai, Hawaii. The two pilots and two rear crew members (who were Croman mechanics) were fatally injured.

Wreckage of Croman Sikorsky S-61N N615CK at PMRF Barking Sands (Credit: NTSB)

The Accident Flight

According to the NTSB safety investigation report published on 26 July 2023 the helicopter was conducting a Part 133 Helicopter External Sling Load Operation (HESLO) to do an inert Mk 48 training torpedo recovery with a conical basket/cage system, under contract to the US Navy.

Croman S-61N N615CK Doing a VIP Flight in 2021 (Credit US Navy / PO 2nd Class Samantha Jetze)

Croman had two S-61Ns at Barking Sands, maintained by three maintenance personnel at the PMRF to support the US Navy’s ongoing Pacific submarine training operations.

According to automatic dependent surveillance-broadcast (ADS-B) data, after the helicopter departed, it proceeded north-northwest to an area about 44 miles away. After maneuvering in the area, the helicopter proceeded south-southeast to return to PMRF. As the helicopter approached the facility, it crossed the shoreline and began a shallow left turn as it maneuvered to the north, into the prevailing wind. As the helicopter neared the predetermined drop-off site, the left turn stopped, and the helicopter proceeded in a northeasterly direction.

Multiple witnesses located near the accident site reported that as the helicopter continued the left turn towards the drop-off site, the turn stopped, and it began to travel in a northeast direction. The witnesses noted that as the helicopter flew about 200 ft above the ground, it gradually pitched nose down and impacted nose first, in a near-vertical attitude.

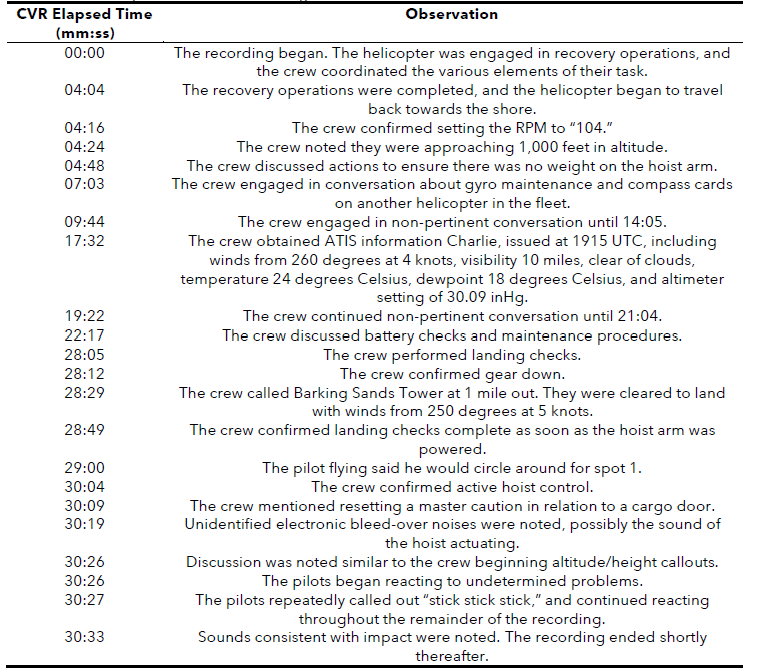

The CVR transcript was as follows:

The helicopter came to rest on its left side on a heading of about 230° magnetic. Three ground scars consistent with main rotor blade impact marks were present near the initial airframe ground impact location. The nose bay door for avionics was found near the start of the debris trail, followed by pieces of debris from the cockpit structure and cockpit instruments, and then the remainder of the helicopter.

The initial ground impact mark and debris trail leading up to the main wreckage was oriented about 65° magnetic. A postcrash fire consumed most of the cockpit and the cabin, though remnant frame sections were present near the main (forward) landing gear as well as the transmission deck.

Wreckage of Croman Sikorsky S-61N N615CK at PMRF Barking Sands (Credit: NTSB)

Safety Investigation

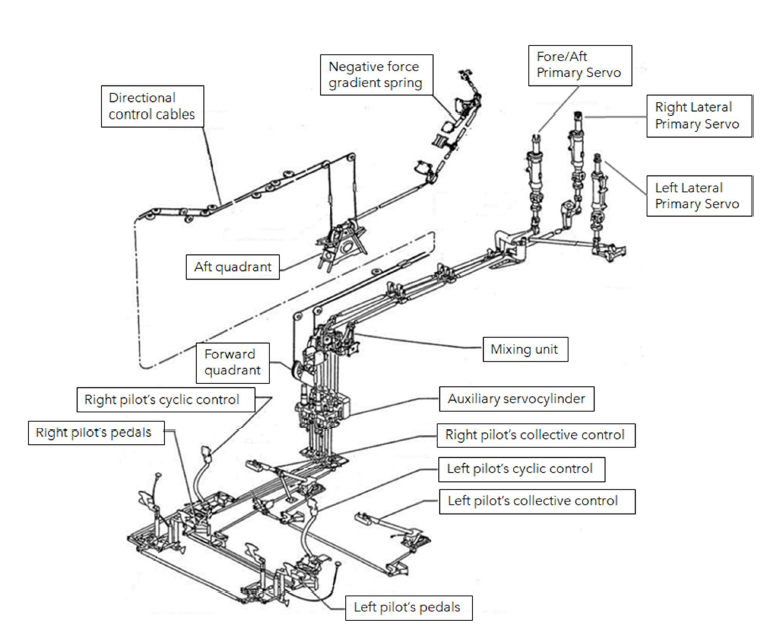

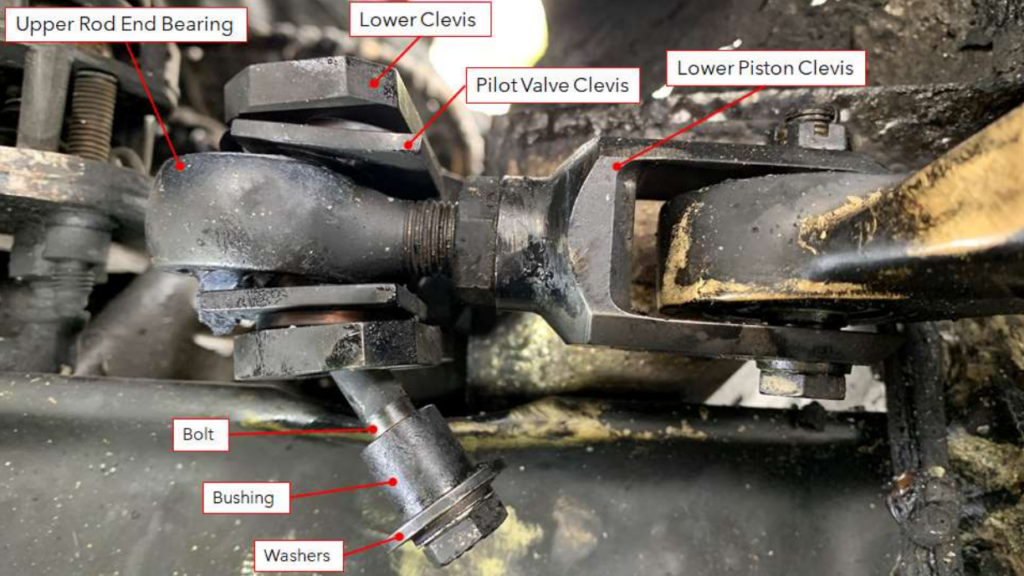

An examination of the wreckage revealed the flight control fore/aft servo input link remained connected at its clevis end to the flight control fore/aft bellcrank, located adjacent to the main gearbox.

However, the rod end was partially connected to the fore/aft servo input clevises and its bolt had mostly backed out of its normally installed position. The bolt exhibited no evidence of fractures or visible deformation and its threads exhibited no unusual wear.

Croman Sikorsky S-61N N615CK The Fore/Aft Servo Input Link Connection (Credit: NTSB)

Therefore, the bolt likely backed out of its normally installed position during the accident flight due to the absence of its nut and cotter pin.

Croman Sikorsky S-61N N615CK Bolt After Removal (Credit: NTSB)

This would have caused an uncommanded input to the fore/aft servo, resulting in the helicopter’s nose-down attitude, and the inability of the crew to control the pitch attitude of the helicopter.

The investigators found that…

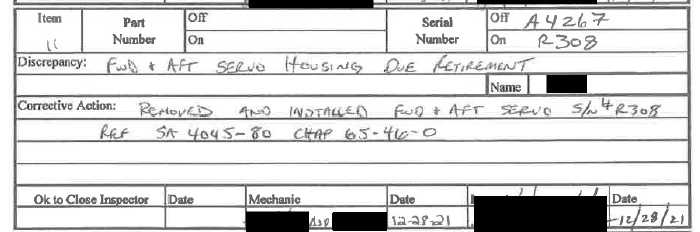

…according to maintenance records, from 17-29 December 2021, multiple maintenance actions were performed. The director of maintenance and another mechanic travelled from the operator’s base in Oregon to PMRF Barking Sands and worked with two additional mechanics, based in PMRF Barking Sands [who were subsequently onboard the accident flight], to complete these maintenance actions.

The fore/aft primary servo of the flight control system was installed on 28 December 2021.

About 7.5 flight hours had elapsed from the time the fore/aft primary servo was installed until the day of the accident.

According to both the director of maintenance [DOM] and a mechanic who travelled to PMRF, when the main gearbox assembly is removed from the helicopter, the primary servos typically remained installed on the main gearbox housing. Furthermore, the primary servos were typically disconnected from the flight control system at each servo input link’s clevis connection to the main gearbox bellcranks. During a primary servo replacement, the servo input link would be removed from the old primary servo and transferred to the new primary servo.

The condition of the removed hardware, such as bolts and washers would be checked and replaced as needed. One-time-use hardware such as cotter pins and nuts with nylon locking features would be discarded after each removal.

NTSB do not discuss whether it was recorded if any cotter pins were issued to this maintenance task. They also do not provide any associated Croman procedures or Maintenance Manual extracts in the public docket.

After all the work on a work order was complete, a company certified inspector inspected all work performed.

In interviews it appears the maintenance personnel worked relatively short shifts and fatigue was not an issue. The DOM and the inspector interviewed stated that there were no distractions during the maintenance.

NTSB concluded that:

The mechanic who installed the fore/aft servo input link to the fore/aft primary servo likely failed to correctly install the attaching hardware.

The company’s certified inspector and who oversaw and inspected all of the work at completion, failed to ensure the hardware attaching the fore/aft servo input link to the fore/aft primary servo was installed correctly.

In interviews NTSB asked about the DOM about the company’s Safety Management System (SMS):

- NTSB Q: Do you have a SMS in place? DOM A: Yes.

- NTSB Q: How long have you had it? DOM A: Before I’ve been here.

- NTSB Q: Do you believe it is effective? Does it help? DOM A: Absolutely.

- NTSB Q: Anything you learn from SMS? DOM A: Yes, we go through the SMS program, and they all do annual SMS training. SMS certificate is placed in their training file.

- NTSB Q: The SMS you had mentioned. Can you expand on the program you have in place here? It is called Prism. An online software. Every employee, pilots, mechanics, fuel truck drivers, all have access to it. They all have a login. It is a cloud-based program, basically. It has all of our manuals, all of our certificates.

- NTSB Q: On average how many reports do you see on a weekly basis? DOM A: Reports are quarterly. Maybe see one quarterly.

- NTSB Q: Can you describe the nature of a typical report you see? DOM A: They are all over the place. Could be a field truck issue, or a pilot issue, or something that happened in-flight, such as a chip light. And we rectify it.

- NTSB Q: Would you consider it part of your SOP for inspectors who find something wrong to disclose that on an SMS form? DOM A: I don’t believe it is in our SOP.

Croman S-61N N615CK in 2021: Note that No Emergency Flotation System is Fitted (Credit US Navy / PO 2nd Class Samantha Jetze)

NTSB Probable Cause

The improper installation of the fore/aft primary servo by maintenance personnel, which resulted in the attaching hardware backing out and which subsequently rendered the helicopter uncontrollable.

Contributing to the accident was the company’s quality control personnel to identify the improper installation before certifying the helicopter for flight.

Our Observations: Independent Inspections, Safety Investigation & Safety Management

While Independent Inspections are a key means to detect errors in critical maintenance tasks, they are not infallible due to confirmation bias. Furthermore it is rare that omissions detected in Independent Inspections result in a safety report / investigation, even in organisations with a sophisticated SMS.

Disappointingly the level of investigation effort into understanding the circumstances of the maintenance here is brief compared to the examination of the wreckage, though the death of two of the mechanics will have hampered the investigation.

The NTSB advocate wider adoption of SMS in the US (i.e. beyond airlines) but the effectiveness of this operator’s SMS was barely probed in interview and not analysed by investigators. Of concern is the description of the SMS being a software product, the low level of reporting and the apparent lack of integration into actual management practices. Unless safety investigators look deeper into the performance and effectiveness of SMS and highlight improvement opportunities, then many organisations are likely to have a false sense of security until their own accident.

Pacific Missile Range Facility, Barking Sands (IATA: BKH, ICAO: PHBK, FAA LID: BKH) Kekaha, Kauai, Hawaii, in 2004 (Credit Polihale CC BY-SA 3.0)

Safety Resources

The European Safety Promotion Network Rotorcraft (ESPN-R) has a helicopter safety discussion group on LinkedIn. You may also find these Aerossurance articles of interest:

- Fatal $16 Million Maintenance Errors

- Misrigged Flying Controls: Fatal Maintenance Check Flight Accident

- S-61N Accident in Afghanistan: Investigators Focus on Auxiliary Servocylinder

- Fatal S-61N Dual Power Loss During Post Maintenance Check Flight

- S-61N Damaged During Take Off When Swashplate Seized Due to Corrosion

- Main Rotor Blade Certification Anomaly in Fatal Canadian Accident

- Canadian B212 Crash: A Defective Production Process

- AAIB Report on the Ditchings of EC225 G-REDW 10 May 2012 & G-CHCN 22 Oct 2012

- EC225 LN-OJF Norway Accident Investigation Timeline

- In-Flight Flying Control Failure: Indonesian Sikorsky S-76C+ PK-FUP

- AAR Bell 214ST Accident in Afghanistan in 2012: NTSB Report

- Airworthiness Directive after Two Fatal Bell 430 Accidents: Main Rotor – Pitch Link Clevis Fractures Angola and South Africa

- Ungreased Japanese AS332L Tail Rotor Fatally Failed

- EC120 Forgotten Walkaround

- Managing Interruptions: HEMS Call-Out During Engine Rinse

- Maintenance Misdiagnosis Precursor to EC135T2 Tail Rotor Control Failure

- Misassembled Anti-Torque Pedals Cause EC135 Accident

- EC130B4 Accident: Incorrect TRDS Bearing Installation

- Loose B-Nut: Accident During Helicopter Maintenance Check Flight

- BEA Point to Inadequate Maintenance Data and Possible Non-Conforming Fasteners in ATR 42 Door Loss

- BA A319 Double Cowling Loss and Fire – AAIB Report

- BA A319 Double Cowling Loss and Fire – AAIB Safety Recommendation Update

- ANSV Report on EasyJet A320 Fan Cowl Door Loss: Maintenance Human Factors

- Tiger A320 Fan Cowl Door Loss & Human Factors: Singapore TSIB Report

- Human Factors of Dash 8 Panel Loss

- EC135 Air Ambulance CFIT when Pilot Distracted Correcting Tech Log Errors

- Fire-Fighting AS350 Hydraulics Accident: Dormant Miswiring

- ATR 72 Rudder Travel Limitation Unit Incident: Latent Potential for Misassembly Meets Commercial Pressure

- Fuel Tube Installation Trouble

- How One Missing Washer Burnt Out a Boeing 737

- B1900D Emergency Landing: Maintenance Standards & Practices

- UPDATE 5 August 2023: A Concrete Case of Commercial Pressure: Fatal Swiss HESLO Accident

You might find these safety / human factors resources of interest:

- James Reason’s 12 Principles of Error Management

- Back to the Future: Error Management

- This 2006 review of the book Resilience Engineering by Hollnagel, Woods and Leveson, presented to the RAeS by Aerossurance’s Andy Evans: Resilience Engineering – A Review and this book review of Dekker’s The Field Guide to Understanding Human Error: The Field Guide to Understanding Human Error – A Review

Aerossurance worked with the Flight Safety Foundation (FSF) to create a Maintenance Observation Program (MOP) requirement for their contractible BARSOHO offshore helicopter Safety Performance Requirements to help learning about routine maintenance and then to initiate safety improvements:

Recent Comments