A Concrete Case of Commercial Pressure: Fatal Swiss HESLO Accident (Lions Air Skymedia AS350B3 HB-ZOJ)

On 11 June 2018 Airbus AS350B3 HB-ZOJ of Lions Air Skymedia crashed while conducting a Helicopter External Sling Load Operation (HESLO) in the Swiss Alps. The helicopter was destroyed and the pilot died. The Swiss Safety Investigation Board (SUST) issued their safety investigation report on 20 September 2022.

Wreckage of Lions Air Skymedia Airbus AS350B3: Overview photo of the scene of the accident around 1½ hours after the accident, taken approximately in the direction of flight: burnt out helicopter (1), point of impact of the helicopter (2), concrete bucket (3), point of impact of the concrete bucket (4) and final position of the end of the transport cable on the helicopter side (5) (Credit: SUST)

A Complex Commercial Context

The local cooperative for rural building was upgrading the Surenen alpine cheese dairy on Alp Ebnet.

In mid-May 2018, the client placed an order with Fuchs Helikopter AG to transport concrete to the construction site…

However, deliveries were requested when Fuch’s only suitable helicopter was committed elsewhere. Hence, these “these orders were passed on to BEO Helicopter AG“. BEO however were not a helicopter owner or operator. They sub-contracted work to Lions Air Skymedia AG (trading as Lions Air Group AG), who owned 50% of BEO.

The morning flights on 11 June 2018 were flown by BEO’s co-owner under Lions Air’s approval. However, they were travelling to the UK later that day so a Lions Air pilot was to take over in the afternoon. The afternoon pilot was experience in HESLO and had c11 years of experience in the local area but had a gap holding an AS350 type rating between October 2015 and April 2018.

The ground party for the tasking consisted of two personnel from Fuchs (referred to by SUST as Marshal 1 & 2) and a Lions Air trainee they had not worked with before (Marshal 3). The afternoon pilot had also never worked with any member of the ground party. A second pilot, Pilot 2, was also on site. They had positioned the helicopter and were due to conduct a subsequent tasking that had been cancelled.

The Pre-Flight Briefing

The afternoon pilot and ground crew met at around 13:00.

Marshal 1 specified that the weather had been discussed and the weather radar consulted and it was agreed that only as much as possible should be done based on the weather. Otherwise the order should be interrupted. There was no time pressure.

However, in contrast:

According to [Marshal] 2, the weather conditions were not mentioned because there was no reason for them.

The investigators comment:

These different views of Marshal 1 and 2 on the relevance of the weather on this mission indicate that there was no common understanding of safety-related aspects, at least relating to the weather.

The Accident Flight

At c 13:30 the HESLO operations commenced using a 20 m line and two cement buckets to be moved one at a time. When laying concrete it is essential to complete the ‘pour‘ in one go.

Because of the changing visibility and fog conditions, [Pilot 1] chose different flight paths for the individual rotations.

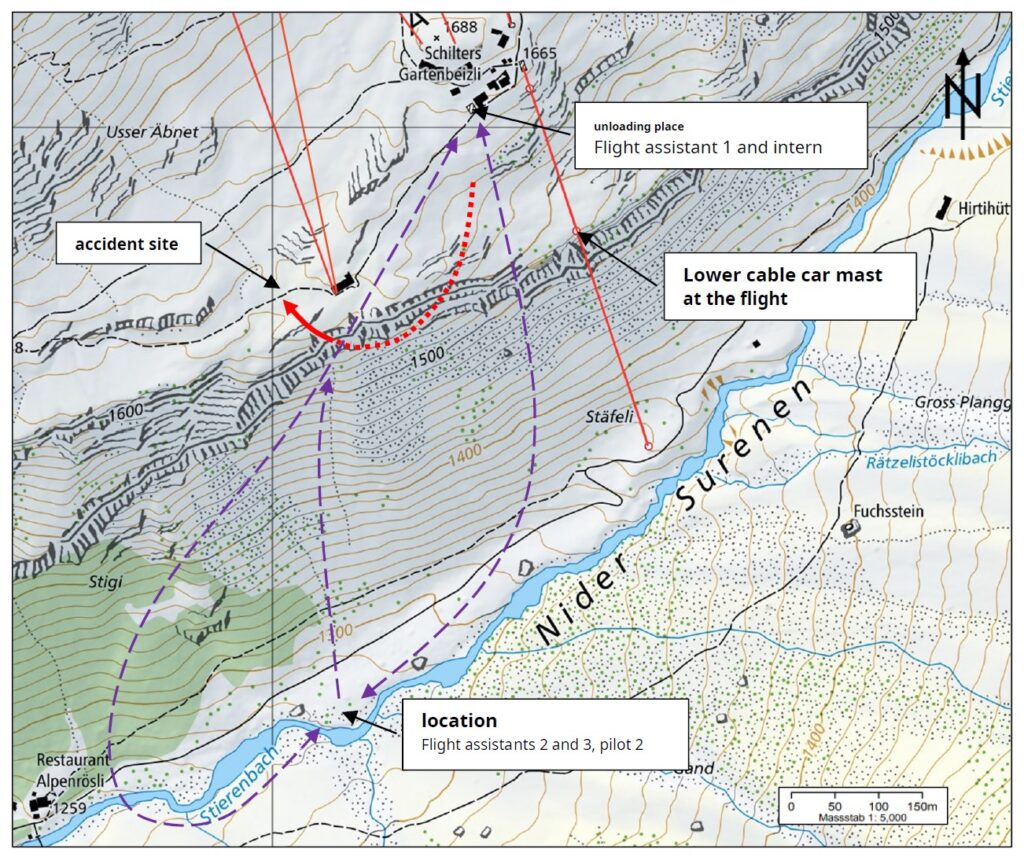

Pick-up and drop-off location with the locations of the respective marshals. The assumed approach and departure routes of HB-ZOJ during the rotations before the accident (dashed purple) and during the flight involved in the accident (dotted red) are shown. The aviation obstacles can also be identified according to the aviation obstacle database of the Federal Office of Civil Aviation (FOCA), which are cables from transport cableways (red lines). Source of the base map: Federal Office of Topography.

After a few rotations, the wind increased from the west.

As a result, more and more wafts of fog appeared between the pick-up and drop-off locations.

By the 7th rotation Marshal 1 warned Pilot 1 by radio that a band of fog was gathering near the lower cable car mast. Pilot 1 acknowledged that the construction site was still clear at that time for landing if necessary.

On each rotation the pilot touched the concrete bucket on the ground to discharge static before positioning to empty the concrete. Marshal 1 now noted the pilot was having difficulty doing this. Pilot 1 called “Danger!” and “Fingers away, fingers away” over the radio and the helicopter climbed away into the fog.

A few seconds later, the people present at the unloading site heard a dull bang. The helicopter collided with the slightly sloping terrain at a distance of around 310 m south-west of the unloading site.

The pilot had suffered fatal injuries on impact in what was assessed as a non-survivable accident. A post impact fire developed. The Emergency Locator Transmitter (ELT) activated but was destroyed shortly after in the fire.

The rotation…was the third or fourth to last rotation of the concrete transport.

Members of the ground party rushed to the accident site.

Due to the bad weather conditions, the Swiss Air-Rescue helicopter was not able to land at the scene…only in the valley near the location.

SUST Analysis

The investigators comment that the the weather situation, with the emerging fog, led to a pressure situation to complete the task.

It is conceivable that [Pilot 1’s] extensive flying experience gave him a false sense of security and led him to exploit the weather situation and ignore the imminent dangers that accompanied it.

The investigators postulate the difficult position the load on the last rotation indicated increasingly difficultly “due to the dwindling visual references”.

Without external visual attitude references, a helicopter in hover or at low forward speed cannot be controlled by the pilot. In the present case, the possible effects of a heavy, oscillating underload made things even more difficult. These circumstances meant that the pilot lost control of the helicopter and it subsequently flew towards the site. First, the concrete bucket collided with the mountainside. The intact condition and end position of the load rope indicate that the pilot then released the load rope even before the helicopter crashed into the terrain.

Other Matters: HESLO Equipment Maintenance & Rigging

Several problems were identified by investigators. Firstly, examination showed that…

…the moving metal parts were poorly or not at all lubricated. This led to increased wear on these components, which over time can lead to component failure.

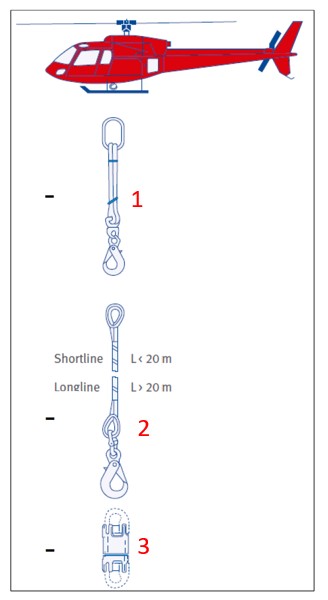

Lions Air Skymedia Airbus AS350B3 HESLO equipment with a thimble (1), safety rope (2), safety load hook (3) and swivel with long link and secondary load hook (4) on the helicopter side (Credit: SUST)

Furthermore:

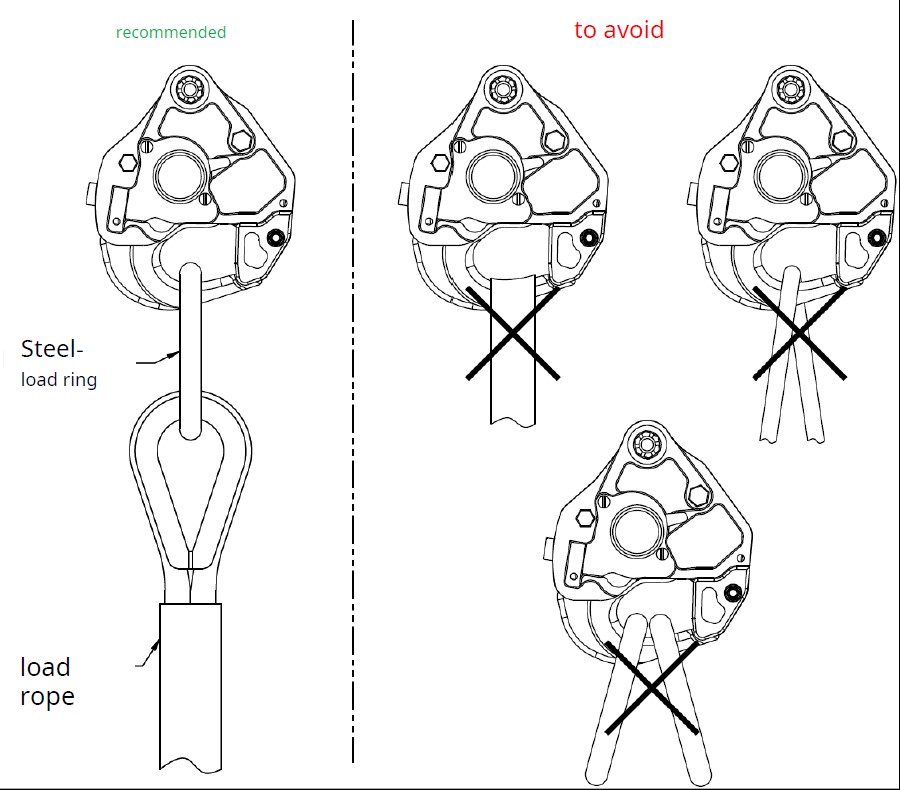

A recommended structure of a load handling device for external loads provides for a shock absorber (damping element) to be attached to the primary load hook of the helicopter using a fitting (steel load ring).

Construction of a load handling device for external loads. Shock absorber (1), load rope (2), swivel (3). (Credit: German Social Accident Insurance eV [DGUV])

The shock-absorber absorbs hard impacts that can damage both the rope and the helicopter structure. The load rope of a suitable length is then latched onto the shock absorber. A swivel with a secondary load hook is attached to the load rope. The purpose of the swivel is to allow the load to rotate.

More specifically:

In the user manual for the primary load hook of the HB-ZOJ (type Talon LC Keeperless Cargo Hook) steel load rings are used as a link between the load hook and the load rope resp. Shock absorbers are recommended to ensure smooth opening and release of the load in all cases and resistance to contamination.

The following arrangements are shown:

The manufacturer also states that belts or ropes made of nylon (or similar material) must not be attached directly to the load hook. If a belt or rope made of this material is used, it must be attached to the load hook using a steel load ring.

The investigators comment:

Regardless of the fact that this circumstance had no demonstrable influence on the course of the accident, the lack of a steel load ring for attaching the load handling device to the primary load hook was considered a safety risk.

The overall rather poor condition of the moving links suggests that little attention was paid to the maintenance of these tools.

Other Matters: Continuing Airworthiness

On 7 May 2018 the helicopter’s Vehicle and Engine Multifunction Display (VEMD) logged a brief torque exceedance and there was a Main Gear Box (MGB) Magnetic Chip Detector (MCD) alert. The debris was found to be within limits but a check was required every 10 hours for the next 30 flying hours. At that point the helicopter had flow 5982 hours. The debris was confirmed to be gear material. The MCD was checked and an oil sample was sent for analysis at 5990 hours and 5999 hours with no further findings. A pilot reportedly checked the MCD at 6010 hours but this was not recorded.

Maintenance records indicated no debris was found again at 6019 hours on 29 May 2018 , however this was contradicted by a “particle detection follow-up sheet’ being raised at the same time. On 4 June 2018…

…the manufacturer informed the CAMO in writing that the MGB should be removed from the helicopter as soon as possible and sent to an authorized maintenance organization for repairs…

The operator made inquiries about sourcing a replacement gearbox but the helicopter continued to operate. On 7 June 2018, at 6044 hours, metal chips were again present on MGB MCD and a regime of checking the MCD every 10 hours continued. At the time of the accident, the helicopter had flown around 6050 hours.

The investigators comment:

During the approximately 15 flight hours between 4 June 2018 and the accident, HB-ZOJ was mainly used for underload transports, during which a helicopter and its drive systems in particular are subjected to particularly high loads.

In view of the high risk associated with a failure of a main transmission gear, the continued operation of the helicopter was not safety-conscious, but had no influence on the accident.

SUST Conclusions

The accident, in which the helicopter with underload collided with the terrain, [was] due to the fact that the pilot cancelled the flight mission too late against the background of the emerging, dense fog and lost control of the helicopter after losing visual references.

The following were identified contributing factors:

- Flight operations involving people from different companies who did not know each other and who did not define a common understanding of safety-related aspects, at least in relation to the weather

- Pressure situation due to an overly optimistic assessment of the weather conditions for a concrete transport

- Insufficient agreement of a reserved decision regarding an interruption or termination of the flight order.

Safety Resources

The European Safety Promotion Network Rotorcraft (ESPN-R) has a helicopter safety discussion group on LinkedIn. You may also find these Aerossurance articles of interest:

- Poor Contracting Practices and a Canadian Helicopter HESLO Accident

- Tool Bag Takes Out Tail Rotor: Fatal AS350B2 Accident, Tweed, ON

- HESLO AS350 Fatal Accident Positioning with an Unloaded Long Line

- Short Sling Stings Speedy Squirrel: Tail Rotor Strike Fire-Fighting in Réunion

- Snagged Sling Line Pulled into Main Rotor During HESLO Shutdown

- HESLO EC135 LOC-I & Water Impact: Hook Confusion after Personnel Change

- Garbage Pilot Becomes Electric Hooker (Helitrans AS350B3 LN-OGA)

- Load Lost Due to Misrigged Under Slung Load Control Cable

- Keep Your Eyes on the Hook! Underslung External Load Safety

- EC120 Underslung Load Accident 26 September 2013 – Report

- Unexpected Load: AS350B3 USL / External Cargo Accident in Norway

- Unexpected Load: B407 USL / External Cargo Accident in PNG

- Fallacy of ‘Training Out’ Error: Japanese AS332L1 Dropped Load

- Inadvertent Entry into IMC During Mountaintop HESLO

- HESLO AS350B2 Dropped Load – Phase Out of Spring-Loaded Keepers for Keeperless Hooks

- Unballasted Sling Stings Speedy Squirrel (HESLO in France)

- Dynamic Rollover During HESLO at Gusty Mountain Site

- Fuel Starvation During Powerline HESLO

- HESLO Baffled Attitude Fuel Starvation Accident

- Ditching after Blade Strike During HESLO from a Ship

- The Curious Case of the Missing Shear Pin that Didn’t Shear: A Fatal Powerline Stringing Accident

- HESLO Dynamic Rollover in Alaska

- Windscreen Rain Refraction: Mountain Mine Site HESLO CFIT

- When Habits Kill – Canadian MD500 Accident

- Loss of Control During HESLO Construction Task: BEA Highlight Wellbeing / Personal Readiness

- Shocking Accident: Two Workers Electrocuted During HESLO

- NZ Firefighting AS350 Accident: Role Equipment Design Issues

- Whiteout During Avalanche Explosive Placement

- Impatience Comes Before a Fatal Fall During HESLO

- EC135 Air Ambulance CFIT when Pilot Distracted Correcting Tech Log Errors

- Managing Interruptions: HEMS Call-Out During Engine Rinse

- UPDATE 6 April 2024: Fatal Fall after HESLO Helicopter Hooks Worker

Airbus has issued several documents to warn of the risks when operating with external loads including Service Letter No 1727-25-05 of 26 March 2006 and Safety Information Note (SIN) No 3170-S-00 of 3 October 2017.

Recent Comments