Fatal Fall after HESLO Helicopter Hooks Worker (AS350BA C-FHAU)

On 20 August 2023, the Expedition Helicopters Airbus AS350BA C-FHAU, was involved in a fatal accident in which a ground crew member died during Helicopter External Sling Load Operations (HESLO). The Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) released its safety investigation report on 28 March 2024.

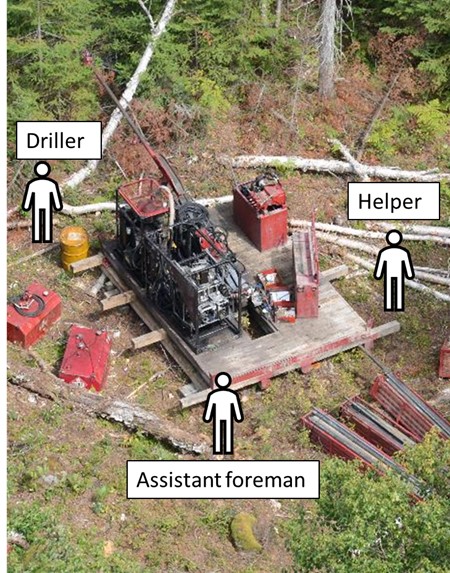

AS350BA C-FHAU: Photo of the new site, with approximate positions of the ground crew members (Credit: Ontario Provincial Police, with TSB annotations)

The Accident

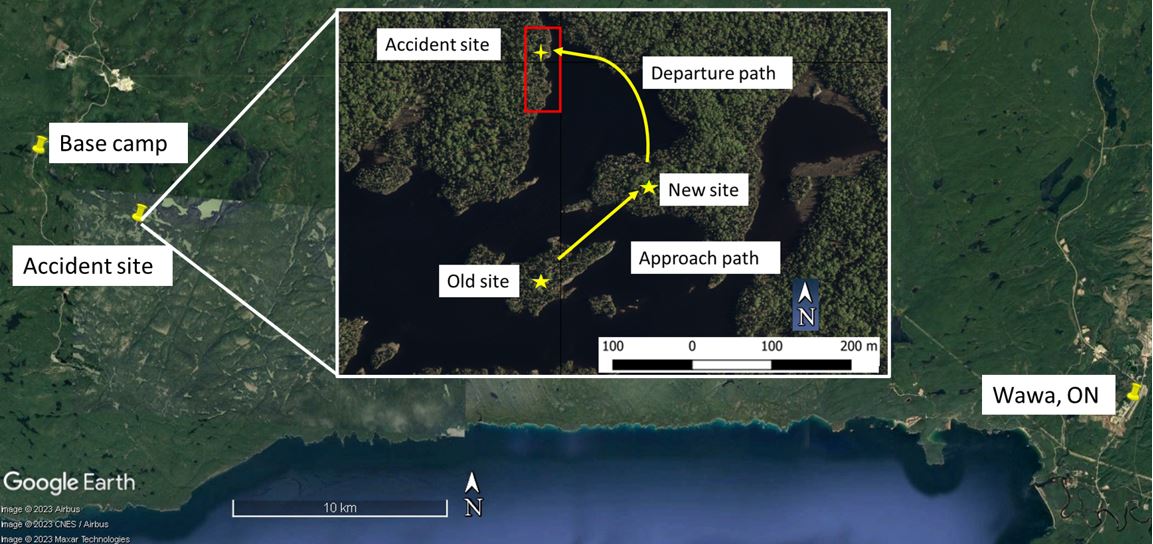

The TSB explain the helicopter was being flown by a single pilot and moving drilling equipment with a 100 ft longline, in support of mining company Angus Gold‘s exploration activities being conducted by drilling contractor G4 Drilling Canada Ltd approximately 25 nm west of Wawa, Ontario.

The pilot had over 4,580 hours total flight time, with 1,210 hours conducting longline operations. The pilot’s door was replaced by a vertical reference bubble window was installed. The conditions allowed day Visual Flight Rules (VFR) flight. The winds at Wawa were reported as being “from the north at 10 knots, variable from 320° to 050° true”.

The pilot’s task consisted of transferring surface drilling equipment by longline from an old drill site on an island to a new drill site on a nearby peninsula, approximately 900 feet away.

AS350BA C-FHAU: Map showing the accident site, with the locations of the old and new drill sites in inset (Credits: Source of main image: Google Earth, with TSB annotations. Source of inset image: Angus Gold Inc, with TSB annotations)

The G4 ground crew consisted of a foreman, an assistant foreman, a driller, and a helper.

The pilot started his duty day at approximately 0615 [Local Time] and flew various short flights for about 2.5 hours. He was then off duty until the first drilling equipment transfer flight, which started at approximately 1520.

The foreman and the assistant foreman were stationed at the old site, preparing and attaching the drilling equipment to the longline, while the driller and helper were at the new site receiving, positioning, and detaching the drilling equipment from the longline.

TSB explain that:

The foreman, driller, and helper had completed all required common core training modules including the speciality module on loading and unloading personnel and equipment from helicopters.

However:

The investigation did not reveal any documentation indicating that the assistant foreman was qualified as a driller or that he had received any of the required common core or specialty module training.

The initial loads were successfully moved.

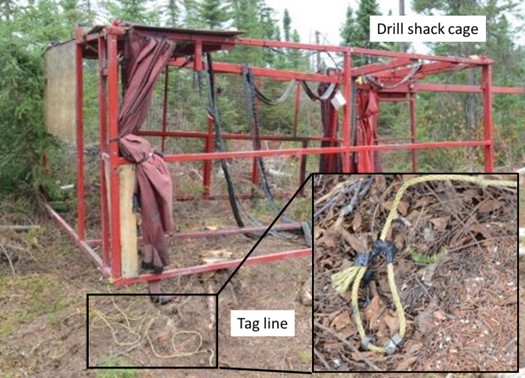

By approximately 1630, only the drill shack cage remained to be moved.

AS350BA C-FHAU: Drill shack cage with tag line (inset) (Credits: Source of main image: Ministry of Labour, Immigration, Training and Skills Development, with TSB annotations. Source of inset image: Ontario Provincial Police)

This cage was to be placed over the drill and equipment on the drilling platform at the new site.

On arrival taglines would be used by ground personnel to rotate the cage to align it. However…

When the helicopter reached the new site with the cage, the pilot, the driller, and the helper had difficulties positioning the cage.

After several unsuccessful attempts, the pilot decided to bring the assistant foreman to the new site to help.

The pilot flew back to the old site, released the cage, picked up the assistant foreman and took him to the new site.

The pilot then returned to collect the cage and delivered it to the new site.

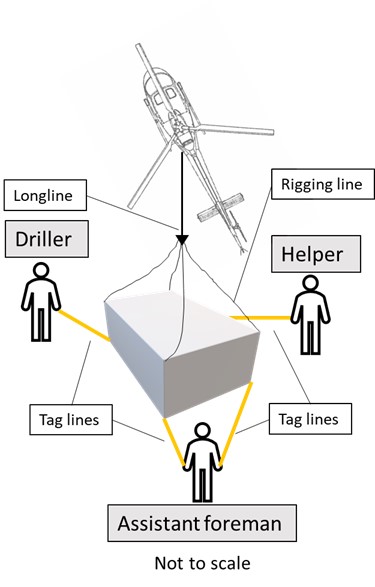

At approximately 1700, the pilot positioned the helicopter into the wind and lowered the cage over the drill. The driller and helper each held 1 tag line and the assistant foreman held 2 tag lines.

AS350BA C-FHAU: Diagram showing the cage, the helicopter (as it would have been oriented 100 to 150 feet overhead), and the tag lines held by the ground crew members (Credit: TSB)

When the pilot looked down through the vertical reference window, he could see the driller and the helper only, because a piece of plywood on top of the cage was blocking his view of the assistant foreman.

There continued to be difficult positioning the cage. The pilot says he called the driller, the only person on the ground with a radio, to say he needed to go and refuel. The driller says he never heard this call.

The pilot began to climb and lifted the cage slowly while paying attention to the cage and any hand signals from the ground crew. As he continued to lift the cage, he did not see any hand signals from the driller or helper, and assumed that he was clear and continued to lift.

As the cage lifted, the assistant foreman became entangled in his 2 tag lines. The driller and helper were concentrating on their own tag lines and did not see the assistant foreman become entangled.

As the helicopter climbed and departed, the assistant foreman was carried aloft.

When the driller and helper realized that the assistant foreman was being carried away, the driller called the pilot on the radio to inform him. However, the radio call was made in French, and given that the pilot did not understand French, he could not understand what was being said. The pilot departed the area and climbed to approximately 200 to 300 feet above ground level over the nearby lake.

A few moments later, the driller and helper saw the assistant foreman fall. At 1722, the driller texted the project lead at the base camp to report the accident.

The pilot was still unaware of the accident but, hearing the tone in the driller’s voice over the radio, felt that something had gone wrong. He proceeded to the old site, dropped off the cage and asked the foreman to accompany him back to the new site. After landing at the new site, the pilot and foreman were made aware of the accident.

The pilot returned to the base camp, refuelled, and returned with 2 passengers to search for the assistant foreman. He was found on land, in a forested area across the lake from the new site, and had been fatally injured.

Safety Investigation

TSB report that:

The investigation determined that the pilot had provided helicopter safety briefings to G4 ground crews at the start of his work on this project earlier in the month. Additional adhoc briefings were provided to the ground crews when various work or safety issues needed to be discussed. Often issues were simply discussed or resolved with the project lead or the foreman and did not require full briefings to all ground crews. There was no formal safety briefing to the ground crew on the day of the occurrence.

In this occurrence, closed weighted loops were made on the end of each tag line. The investigation determined that some G4 ground crew members put their hand in the loop or wrapped the tag line around an arm, wrist, or hand when handling the tag line attached to a load. Although the company did not have a standard procedure on how to use tag lines, this technique was a common practice with company crews. The investigation was unable to determine if the assistant foreman used this technique.

TSB highlight previous occurrences in Canada, Australia and Sweden that Aerossurance has previously summarised:

- Keep Your Eyes on the Hook!: A Canadian Coast Guard incident video and an Australian helirig occurrence.

- Impatience Comes Before a Fatal Fall During HESLO: a fall in Sweden

Safety Actions

- Angus Gold has implemented an indoctrination session, which includes information on helicopter safety for persons, including contractors, accessing drill sites and working near or with helicopters. All indoctrination sessions and other required training are documented.

- Angus Gold has also purchased noise-cancelling helmets that can be connected to the radios, and has implemented procedures for using these helmets when conducting longline operations.

- G4 has modified its tag lines such that the thickness and rigidity of the line do not allow it to coil upon itself, making it more difficult to catch or entangle a person handling the line or equipment on the ground.

TSB Safety Messages

- Pilots are reminded to ensure that all ground crew members are clear of loads before lifting the loads off the ground.

- At the same time, ground crew members need to be trained and must exercise caution and vigilance when working with external loads to avoid situations that could lead to entanglement.

- Personnel who operate radios are reminded that communications need to be made clear by using language and terminology that can be understood by all parties involved, and these transmissions should be acknowledged to ensure that the message is understood.

- In addition, the communications equipment needs be suitable for the task and take into consideration the environment in which the communications are being made.

Our Safety Observations

The absence of regular daily briefings (‘toolbox talks’), or indeed end of day debriefings, reduced the opportunity to maintain alignment and avoid ‘drift’.

It would probably be more value if the end customer examined their contractors training and assured themselves that it was adequate and delivered comprehensively than delivering their own (Safety Action 1 above). Alternatively if extra training is required perhaps it should be delivered by the helicopter operator.

We have previously examined a case of: Poor Contracting Practices and a Canadian Helicopter HESLO Accident

UPDATE 4 May 2024: NTSB has reported on another drill shack entanglement, involving Soloy Helicopters AS350B3 N297SH in Alaska on 16 September 2023. In that case the ground team member suffered serious injuries.

Safety Resources

The European Safety Promotion Network Rotorcraft (ESPN-R) has a helicopter safety discussion group on LinkedIn.

As well as the three articles highlighted above, you may also find these other Aerossurance articles of interest:

- Snagged Sling Line Pulled into Main Rotor During HESLO Shutdown

- Garbage Pilot Becomes Electric Hooker

- Load Lost Due to Misrigged Under Slung Load Control Cable

- Keep Your Eyes on the Hook! Underslung External Load Safety

- EC120 Underslung Load Accident 26 September 2013 – Report

- Unexpected Load: AS350B3 USL / External Cargo Accident in Norway

- Unexpected Load: B407 USL / External Cargo Accident in PNG

- Fallacy of ‘Training Out’ Error: Japanese AS332L1 Dropped Load

- Inadvertent Entry into IMC During Mountaintop HESLO

- HESLO AS350B2 Dropped Load – Phase Out of Spring-Loaded Keepers for Keeperless Hooks

- Unballasted Sling Stings Speedy Squirrel (HESLO in France)

- Dynamic Rollover During HESLO at Gusty Mountain Site

- Fuel Starvation During Powerline HESLO

- HESLO Baffled Attitude Fuel Starvation Accident (Haverfield Aviation Hughes 369E N765KV)

- Running on Fumes: Fatal Canadian Helicopter Accident

- UH-1H Fuel Exhaustion Accident

- Ditching after Blade Strike During HESLO from a Ship

- The Curious Case of the Missing Shear Pin that Didn’t Shear: A Fatal Powerline Stringing Accident

- HESLO Dynamic Rollover in Alaska

- Windscreen Rain Refraction: Mountain Mine Site HESLO CFIT

- Loss of Control During HESLO Construction Task: BEA Highlight Wellbeing / Personal Readiness

- Shocking Accident: Two Workers Electrocuted During HESLO

- HESLO EC135 LOC-I & Water Impact: Hook Confusion after Personnel Change

- HESLO AS350 Fatal Accident Positioning with an Unloaded Long Line

- A Concrete Case of Commercial Pressure: Fatal Swiss HESLO Accident

Airbus issued Safety Information Note (SIN) No 3170-S-00 on 3 October 2017.

See: UK CAA‘s CAP 426: Helicopter External Load Operations too.

Recent Comments