Poor Contracting Practices and a Canadian Helicopter HESLO Accident (Heli-Express Airbus AS350B2 C-GHEX at Hydro-Quebec Powerline Worksite)

On 11 May 2021, Héli-Express Airbus AS350B2 C-GHEX was conducting Helicopter External Sling Load operations (HESLO) flights from a staging area to a 315 kV powerline maintenance site, northeast of Les Escoumins, Quebec.

During one HESLO flight the loadmaster notified the pilot by radio from the ground that the load was oscillating. The pilot expected the load would stabilise as the helicopter accelerated. At an airspeed of c65 knots, the load struck the tail boom however. The pilot pitched up to slow the helicopter and jettisoned the load which then struck the tail rotor. The pilot subsequently lost control of the helicopter and made a forced landing in sparsely wooded rugged terrain. The pilot suffered serious injuries.

Wreckage of Heli-Express Airbus AS350B2 C-GHEX (Credit: Sûreté du Québec)

The helicopter was contracted to GLR a specialised powerline construction and maintenance company, who were contracted by power utility Hydro-Québec. The Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) discuss important contracting issues and commercial pressures in their safety investigation report (issued 10 January 2023).

The Safety Investigation

We start by considering the last portion of the flight, after the load impacted the helicopter. But to understand why the load behaved as it did we then step right back to understand the organisational factors that were influencing the operation.

Safety Investigation: The Flight After the Load Instability

Examination of the load confirmed that it was struck in its understated by a tail rotor blade as the blade rotated backwards.

Load from Heli-Express Airbus AS350B2 C-GHEX (Credit: Heli-Express)

The TSB explain that after the load was jettisoned:

The pilot immediately realized that the anti-torque pedals were no longer allowing him to control the yaw, and he quickly experienced difficulty maintaining control of the aircraft.

As part of their recurrent training the pilot had practised a technique described in the Rotorcraft Flight Manual that assumed a loss of tail rotor control (but not a loss of tail rotor thrust).

In such a case, it is still possible to land with the engine running.

The absence of tail rotor thrust cannot be reproduced in flight for training purposes (Héli-Express do not appear to use simulators). With a loss of tail rotor thrust…

To land, the pilot must conduct an autorotation while shutting down the engine.

As the pilot did not think he had lost the tail rotor…

After regaining speed, the pilot headed to a landing strip near the staging area to land with the engine running, like he had learned to do in training.

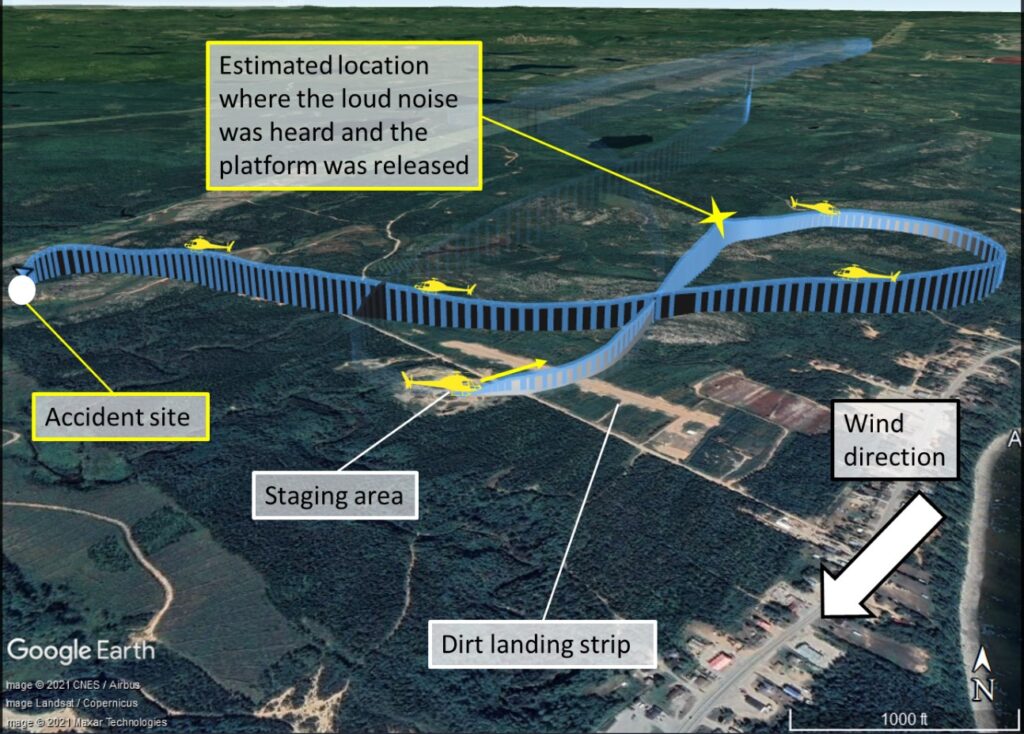

Flightpath of Heli-Express Airbus AS350B2 C-GHEX (Credit: TSB)

However, after losing and regaining control of the aircraft’s yawing motion twice while heading to the landing strip, his speed and altitude were too low to take back full control of the aircraft when he lost control of the yawing motion a 3rd time.

When power was cut, the helicopter was likely at a height that could not sufficiently dampen the autorotational descent…

TSB note (our emphasis added)

Héli-Express’ training program also includes ground and flight training on the transport of Class B external loads [i.e. suspended loads that can be jettisoned] and operations near high-voltage transmission lines, including flying under the lines. However, the exercises for practising flying near or under high-voltage transmission lines do not include practising transporting a sling load in this particular environment.

The pilot had been employed by the operator since 2018 and had 3,185 hours total time, 1,465 on type and 211 hours of HESLO operations.

He had also taken flight training for operations near high-voltage transmission lines, including flying under the lines, on 06 October 2020, and for the transport of Class B external loads on 08 October 2020.

There is no indication on what further supervised flying the Héli-Express did for new HESLO pilots but further training seems to have been primarily on the job.

Safety Investigation: The Organisations and Hydro-Québec’s Procurement Process

The Helicopter Operator: Héli-Express

Formed in 1989, the company operates Airbus AS350s, BK117s, and a Bell 205, under an Air Operator Certificate for Part 702 (Aerial Work) and 703 (Air Taxi) operations. They are “one of the helicopter operators qualified by Hydro-Québec to work at its sites” and since 2018 were striving to specialise in powerline work. In this case Héli-Express was contracted by GLR.

GLR

Formed in 1970, the company has 30 permanent employees and can grow to 300 employees during major contracts. Their contracts peak during the summer months. They are one of 11 companies qualified by Hydro-Québec for powerline construction / maintenance. GLR works “exclusively, or almost exclusively, for Hydro-Québec” but according to the TSB had no in-house or contracted aviation expertise to provide independent assurance or advice.

Hydro-Québec

Hydro-Québec is a public utility with c20,000 employees.

Maintenance of existing transmission lines is normally carried out by Hydro-Québec employees, while transmission line construction and modification are carried out by specialized transmission line construction contractors…

[B]ecause of Hydro-Québec’s limited in-house capacity to perform insulator replacement on its extensive network of transmission lines, it must rely on specialized contractors to perform this maintenance work, as was the case in this occurrence.

Hydro-Québec has 3 divisions:

- Hydro-Québec Production [Production];

- Hydro-Québec TransÉnergie et Équipement [TransEnergy and Equipment];

- Hydro-Québec Distribution et Services partagés [Distribution and Shared Services]

The TransÉnergie et Équipement division is responsible for the network of 34,000 km of power transmission lines.

When any external contractors are needed, another department, the Direction principale – Approvisionnement stratégique [Strategic Procurement Department] (DPAS), posts Requests for Proposals (RFPs) to pre-qualified suppliers. Successful suppliers are then subject to an evaluation every year against three criteria:

- Quality of goods and services (30%)

- Ability to meet contractual commitments (including meeting deadlines), and occupational health and safety (60%);

- Business relationship (10%).

Surprisingly, TSB do not comment on the problematic combination of safety and achieving deadlines in the second criteria. Furthermore its not clear if flight safety is even considered as the metric is described as “occupational health and safety”. We discuss the role of deadlines further in the next section.

TSB say that Hydro-Québec takes the scores into account for future contracts. The difference between the best and worst is equivalent to a 10% cost difference and TSB comment that Hydro-Québec “reserves the right to negotiate the price while reviewing compliant bids”.

TSB state that:

The Direction – Services de transport [Transportation Services Branch], which is part of the Centre de services partagés, is responsible for managing Hydro-Québec’s aircraft fleet, charters (airplanes and helicopters), remotely piloted aircraft systems and flight following, among other things.

Despite the impression this statement might give, the TSB do clarify that Hydro-Québec does not own any helicopters and helicopter operations are all contracted (directly or, as in this case, indirectly).

At a March 2019 conference of the Association québécoise du transport aérien (AQTA) [Quebec Air Transportation Association] Hydro-Québec explained that the company had…

….modified the terms and conditions related to [aircraft] charter management and administration to cut down on costs. Hydro-Québec also explained that the free-trade environment made it possible to open the market to suppliers outside Quebec, increase its pool of qualified suppliers, and obtain competitive prices.

TSB state, without elaboration, that Direction – Services de transport is…

…responsible for overseeing and supervising flight safety during operations, which includes surprise inspections at work sites.

However, elsewhere in their report TSB clarify that when aircraft are not directly contracted (e.g. when a Hydro-Québec contractor charters a helicopter), it is the contractor not Hydro-Québec that is responsible for oversight of their chosen air operator and the Direction – Services de transport is not involved.

The efficacy of Direction – Services de transport ‘oversight and supervision’ appears suspect. TSB not that “between 2015 and 2021” there were “24 incidents, including [at least 7] losses of loads in flight…during sling operations conducted under contract for Hydro-Québec”.

With the data gathered during the investigation, it was not possible to determine whether these load losses were full or partial; however, none of the load losses in flight were reported to the TSB. The loss of a load in flight is an aviation incident that must be reported to the TSB (SOR/2014-37, Transportation Safety Board Regulations, subsection 2(1)).

This is not an unusual failing, namely an organisation that does not hold any aviation approvals, being aware of incidents but not reporting them as they have no obligation to communicate with aviation regulators or accident investigators. The air operators should have reported many of these occurrences, hence one must question the contractual oversight by Hydro-Québec and whether their contracting approach discouraged reporting.

Of note is that of these 24 incidents, 9 were in the 4 years between 2015 and 2018, three were in 2019, none were in 2020 and but 7 occurred in 2021. While not considered by TSB, one might suppose that due to COVID, the 2020 Hydro-Québec work programme may have been significantly curtained, whereas 2021 may have been busy to deal with the backlog.

On 20 November 2019 AQTA organised a meeting between its helicopter operator members who were qualified suppliers of Hydro-Québec and Hydro-Québec Direction – Services de transport management. The meeting identified three key issues:

- labour shortages

- work planning by Hydro-Québec

- contract review

These are relevant to how the actual accident related contract panned out. TSB also explain that a 2015 reorganisation had also “weakened” Direction – Services de transport “decision-making powers regarding contracts involving helicopter operations” that Hydro-Québec did issue. This does suggest that the meeting organised by AQTA was with an isolated staff function with little influence over the actual procurement process. This is reinforced by Hydro-Québec holding an information session on 26 February 2020 regarding new contract clauses specific to air operators

Dissatisfied with the new clauses, the operators asked for the implementation to be postponed so that they could discuss the clauses among themselves. Hydro-Québec declined the request.

On 5 November 2020, AQTA wrote to Hydro-Québec to express concerns “with regard to certain actions being taken that had a negative impact on the safety and effectiveness of helicopter operations”.

Only in 2021 after 14 safety occurrences in 8 months (including this accident and one unreported to TSB on 14 April 2021, in which a helicopter’s main rotor struck a transmission line north of Forestville, Quebec, while a tower was being inspected) did progress occur:

Since then, several topics of concern that could negatively affect the safety of operations have been addressed with Hydro-Québec, including the absence of standardized working methods for slinging and the awarding of contracts to the lowest bidder.

Of concern (our emphasis added) is that:

According to the operators, this method of awarding contracts negatively impacts their ability to invest in maintaining and enhancing the safety of operations (e.g., by purchasing specialized equipment and providing pilots with more training).

Safety Investigation: This Project (& Contract)

GLR was awarded the contract for the replacement of 315 kV transmission line insulators spread throughout several administrative regions…

This was the first such contract GLR had been awarded on 315 kV lines although they had done the same task on 735 kV line. Of note in this accident is that:

Replacing insulators on 315 kV high-voltage transmission lines requires the use of a long ladder or ‘platform’, unlike work performed on 735 kV high-voltage transmission lines.

Incredibly, the contract was awarded just 14 days before work needed to commence. While the average is 40 days, seemingly 14 days is not unusual and…

…suppliers complain that this is often too short an interval to properly prepare for the work, putting additional pressure on them.

TSB don’t consider if the prequalification process may inadvertently facilitate last minute contract awards.

In addition to having to prepare the documentation required by Hydro-Québec (working methods, etc.), suppliers may encounter problems hiring enough qualified workers, obtaining the required materials in time, and preparing the work area…without the possibility of an extension.

GLR was contractually responsible for the following tasks:

- supplying labour, machinery, and certain materials

- deforestation as necessary

- transporting material from where it was available to where it was needed for work purposes

- site rehabilitation after work was completed

Hydro-Québec did not allow GLR to use its depot or buildings as staging areas. GLR had to find sites along the transmission line and rent construction trailers that could be moved periodically as work progressed.

Hydro-Québec did not require that helicopters were used. That was a decision for the contractor (GLR) to determine. However, if they do, the must choose an air operator prequalified by Hydro-Québec (of which there are 21). TSB fail to consider where the existence of a Hydro-Québec list of prequalified air operators actually subverts the need for the construction / maintenance contractors to do their own due diligence and creates a false sense of security.

While planning the work the contractor must produce a series of ‘working method’ documents for individual tasks or techniques that are approved by Hydro-Québec.

The document details the steps to be taken to perform the work. It also highlights any hazards and risks associated with the work, and the safety measures to be followed. Generally speaking, working methods are reference documents for the work to be performed by line workers.

In the case of this contract:

GLR was evaluated based on its performance at the Les Escoumins work site, and had to meet several deadlines in submitting documentation and in performing the work on the transmission lines.

Missing any deadlines or dates indicated in the contract would lower its performance rating, and it could face a monetary penalty per tower if the insulator replacement was not completed by the date stipulated in the contract.

TSB comment that:

If financial and time pressures interfere with proper operational planning, risk management, and risk mitigation efforts, resources may be focused on completing the work without placing enough emphasis on safety.

Safety Investigation: Conduct of HESLO

Hydro-Québec did require a ‘working method’ for any HESLO. TSB explain this was not a procedure for pilots but for the ground team who prepare and hook up the loads.

It did, however, include a “hold point,” or a pause in operations, in case a new situation or one not covered by the working method arose. The purpose of the hold point is to give time to think about and decide on an action, and can lead to changing the initial working method, if necessary.

GLR’s working method was based on the one Hydro-Québec had previously approved for insulator replacement contracts on 735 kV transmission lines and included:

- images of known loads to be transported near hydro towers

- methods for securing known loads

- sling material provided (straps, swivels) and how to use it

- communication signals to be used with the pilot

Crucially:

GLR did not consult Héli-Express, but rather used its own knowledge gained in the field and its own experience with Héli-Express. The working method in question was approved by 2 Hydro-Québec representatives from 2 different groups: Santé et sécurité au travail [Occupational Health and Safety], and Équipement [Equipment].

These external approvals no doubt reassured GLR. Furthermore:

Once the working method was approved, GLR communicated it to all of the workers, but not to the pilots or Héli-Express’ loadmaster.

TSB don’t provide any further detail on the ‘working method’, noting that:

If contractors and subcontractors do not maintain close communication, they may not have a clear understanding of their shared and unique risks or mitigation measures. Consequently, they may focus on their own operational goals and leave significant risks unmitigated

TSB do explain that Héli-Express management did intervene after one of their pilots expressed concern about large ladders being carried unfolded on the side of trailers to save time.

Trailer with Ladder Attached of Heli-Express Airbus AS350B2 C-GHEX (Credit: Heli-Express)

The Héli-Express operations manager immediately informed the site manager that he did not approve of this method, and said that from now on, ladders needed to be collapsed and stored in the trailers if they were being transported without a sling.

GLR, which had adopted this method and deemed it safe and efficient, found this decision frustrating and did not understand the reason for it, especially since the first pilots had accepted it without expressing any particular safety concerns.

The latter point is important. Its a common issue, often at landing site and on helidecks for example, where acceptance of defects or degradations by one pilot can far too easily be taken by non-aviators as a confirmation of adequacy, creating what Diane Vaughan in her masterpiece ‘The Challenger Launch Decision‘ as ‘normalisation of deviance‘ (accepting a deteriorated condition as a new baseline).

Of note too is that:

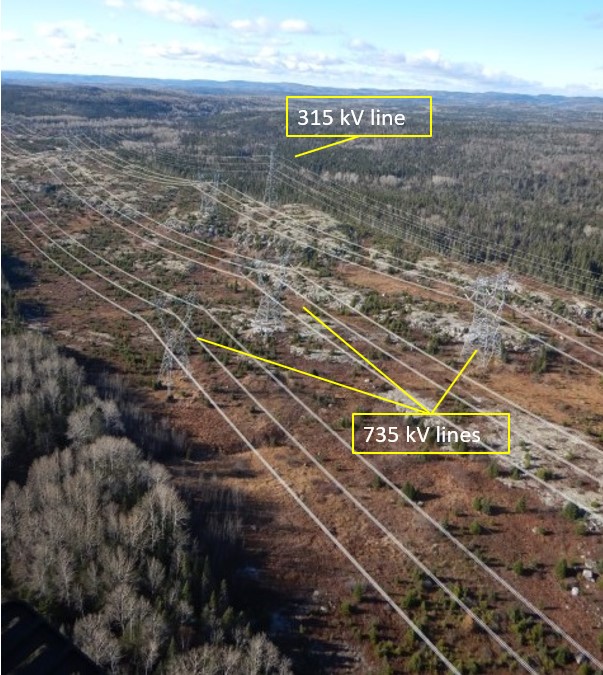

The section of transmission line requiring work was located near 3 parallel 735 kV high-voltage transmission lines.

Heli-Express Airbus AS350B2 C-GHEX Powerline Worksite near Les Escoumins, QC (Credit: TSB)

Vegetation below the 315 kV lines and the adjacent 735 kV lines “were considered to be high risk factors”. GLR’s work teams loads to dropped off as close as possible to the towers.

In this context, the helicopter would have to fly under the three 735 kV transmission lines to drop off the loads…because there was often too little space to fly directly under the 315 kV transmission line.

TSB express no concerns about flying loads under live powerlines, even though they also note that Héli-Express’ training did not cover this technique.

Héli-Express however initially decided to use a 150 ft long line instead. This meant the loads would be deposited in the ‘right of way’ (i.e. between the tower and the tree line) rather than under the powerline. This would mean greater ground movement of loads at the work site, that presumably GLR had not expected when they committed to the Hydro-Québec deadlines.

The work began in early April [2021] with one helicopter, one pilot, one loadmaster and one 150-foot sling. A second helicopter was dispatched shortly thereafter, but it did not have an additional sling.

In addition to transporting loads, every morning and on request throughout the day, the helicopters had to carry 8 teams of 4 line workers and 2 teams of 4 brush cutters from the staging area to various work sites. The site manager had to manage approximately 50 people altogether. Each day would begin with a safety briefing attended by the pilots, the site manager, and all of the workers.

On 25 April, one of the 2 pilots was replaced by a 3rd pilot (the occurrence pilot). At the flight crew changeover meeting, the new pilot was informed that loads were no longer being transported with the 150-foot sling, but were being suspended directly from the cargo hook mounted on the belly of the helicopter. This method offered greater flexibility for helicopter operations and helped save time.

There were other operational impacts of the choice to use a longline, and only having one on site:

The workers and material had to be moved constantly throughout the day. A helicopter that had just dropped off a load with the 150-foot sling could not fly under the transmission line to pick up a team ready to be moved without first unhooking the sling at the closest depot. Also, the 2 helicopters could not transport material at the same time because only one 150-foot sling was available, resulting in longer wait times for teams.

Furthermore:

The occurrence pilot had little experience transporting loads with a long sling and was not comfortable with the idea of working with a 150-foot sling in conditions where there were time and efficiency pressures. The other pilot had more experience using a long sling and was the only one who used it occasionally.

Safety Investigation: Why Did the Load Become Unstable?

The accident load was a work platform, called for because one at the work site had been damaged. It was approximately 6 m long and weighed approximately 55 kg. When such a load had been moved a week before, attached at one end to a sling it was observed it be unstable. So a new technique had been trialled and used at least twice before successfully.

TSB describe the load as being carried without a sling. In practice a short strap on the load was hooked directly to a swivel fitted to the belly hook.

Platform HESLO Trial Heli-Express Airbus AS350B2 C-GHEX (Credit: screen shot of a video filmed by the occurrence pilot during the test flight via TSB)

Transporting loads without a sling carries additional risks, including the risk of the load striking the helicopter’s tail.

Furthermore, TSB say the swivel was actually “designed for cable pulling (to roll out electrical wiring when installing a line above ground or underground, for example), not for lifting a load”.

Heli-Express Airbus AS350B2 C-GHEX Swivel (Credit: TSB)

TSB note that past incidents with swivels were known to Hydro-Québec but not shared with their contractors. Diane Vaughan labelled this phenomena ‘structural secrecy’, where organisational structures prevent the flow of necessary information.

With limited experience in transporting external loads, the occurrence pilot was most likely unable to properly assess all of the risks involved in carrying the platform horizontally.

However:

He took matters seriously and followed the procedure for unusual loads described in Héli-Express’s operations manual: he informed the operations manager of the decision and sent the manager the video that was filmed during the test flight, which was deemed satisfactory.

Safety Investigation: TSB Analysis of Work Pressures

Replacing transmission line insulators is subject to tight deadlines because the power circuit being worked on needs to be shut down. Any delays, even if they are beyond the supplier’s control (e.g., weather conditions), can put time pressures on the supplier[i.e. GLR] and indirectly on any subcontractors [i.e. a helicopter operator].

Any deadline that is not met results in a monetary penalty, adding to the financial pressures already being felt by the supplier because it had to submit the lowest bid possible in order to be chosen from among all the bidders. If the contract[or] cannot absorb all of these costs on its own, it is possible that the various subcontractors it uses will do what they can on their side to work as fast as possible. To get the job done, they may adapt certain working methods that may reduce the safety margin in favour of productivity.

This is especially the case where meeting deadlines and safety are scored together in a performance management metrics.

In this occurrence, the pilots were aware of the need to minimize time loss.

With only one 150-foot sling available that brought the temptation to attach loads direct to the belly hook.

Not only did transporting loads suspended directly from the cargo hook attached to the belly of the helicopter better meet GLR’s needs for efficiency, it also gave pilots the ability to choose whether or not to use the 150-foot sling, based on their experience.

Faced with these pressures, the pilots preferred to transport the loads without a sling to save time.

Diane Vaughan calls this a ‘culture of production’ where production pressure gets normalised. However…

Transporting loads without a sling carries additional risks, including the risk of the load striking the helicopter’s tail.

TSB Conclusions

TSB opine that the safety margin is less…

…when operators delegate the management of many operational hazards to flight crew, who are in direct contact with customers.

By implication this is when frontline flight crew are left to make decisions, under the influence of customers, without specialist / management support or well defined company procedures and limitations to guide them.

When unsafe practices have no adverse consequences and provide good results (satisfied customers), it may seem rational to accept them. They end up becoming the norm and are no longer considered to present risks.

Noteworthy by its absence is any TSB comment on the aviation regulator, Transport Canada.

Safety Recommendations & Safety Actions

TSB make no safety recommendations and they only summarise safety actions taken by Hydro-Québec (not GLR, Héli-Express or Transport Canada).

Hydro-Québec have reportedly hired more aviation safety advisors and are planning more “site visits and surprise audits”. They also are going to impose their own training and HESLO standards on to actual air operator certificate holders (potentially unhelpfully emphasising their ‘work as imagined’ over the ‘work as done’ by experienced frontline practitioners).

However, no action appears directed to resolving the issues with how work is contracted and the associated commercial pressures.

Our Safety Observations on Dysfunctional Procurement Practices and How to Avoid Them with a Vested Contracting Approach

The TSB report suggests a fairly dysfunctional procurement and contract management process driven primarily by policies and practices of the end customer. The considerable commercial pressures include:

- The end customer, a very large corporation, had a procurement process that placed contracts at short notice, to the lowest bidder from a pre-qualified pool of 11, far smaller, powerline contractors.

- The contracts had penalties for late performance (presumably significant for smaller suppliers).

- Performance achieving schedule was paradoxically mixed with safety in a metric that influenced future contracts (and again the future of small suppliers).

- The end customer’s late contract award and emphasis on schedule made helicopters even more important to the work.

- The powerline contractors were limited to only use helicopter operators the end customer had pre-qualified.

- It does not appear that the powerline contractors were required to demonstrate they had the expertise to procure and assure aviation services and ensure their use of helicopters was conducted safely.

- Approvals of the working methods by the end customer and the pre-qualification of the helicopter operators may well have given the pressured powerline contractor a false confidence.

- The end customer forbid their contractors using their property for helicopter operations, adding further service delivery challenges.

- The nature of the prime contract will have most likely resulted in cost and schedule pressures being flowed down to the chosen helicopter operator and in turn this did result in an increase in risk (e.g. operating under powerlines, not using slings to allow manoeuvring closer to pylons, carriage of dubiously configured loads etc)

The combination of pressures on to keep the contrasted price low and achieve tight deadlines conspire to put pressure on safety as illustrated by this migration model from Jens Rasmussen:

Rather than address these fundamental weaknesses the end customer has seemingly chosen to conduct more frontline audits in future and, as a non-aviation company, to impose their own HESLO standards and training on air operators that often aren’t even contracting themselves (as in this case). This is rather like King Canute, trying to command the tide (in this case of cost and schedule pressures of Rasmussen’s model) to halt. This is behaviour that is not uncommon of non-aviation organisations with in-house aviation teams are like ‘shadow organisations’, attempting to duplicate the expertise of their suppliers, that need to be seen to be ‘busy’ (i.e. doing ‘things’ to their contractors) to justify their existence but have little influence within their own organisation.

Pre-qualifying large numbers of contractors (Hydro-Québec had 21 pre-qualified helicopter operators) and selection of the lowest bidder results in commoditisation and inevitably discourages proactive safety management and investment in anything beyond that needed to stay on the pre-qualified list. You can’t ‘audit in’ success if you start with less competent, poorly organised and badly resourced contractors. although some large corporations seem to believe that fallacy.

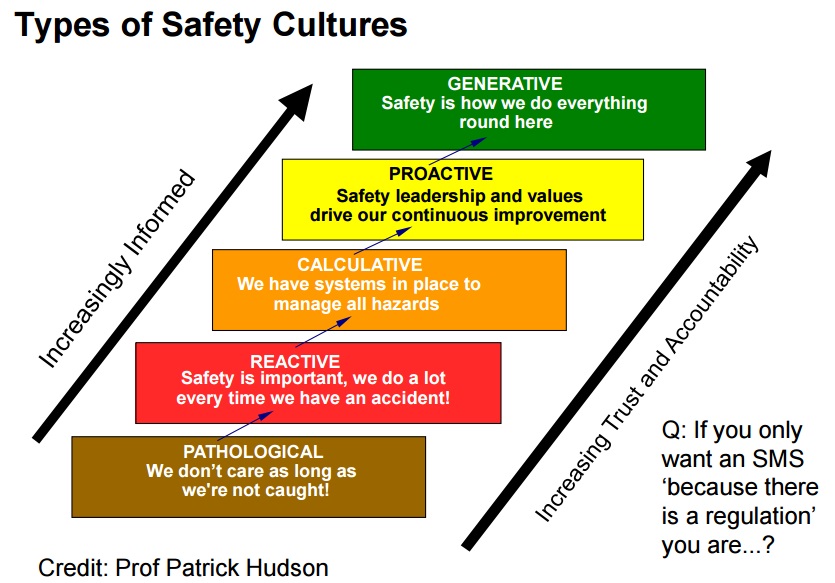

Prof Patrick Hudson proposed the following safety culture model, developed from earlier work by Ron Westrum:

In cases like this, perhaps the Reactive level is one where ‘safety is important, we do a lot on other people after an accident’…

In this case, though the end customer volunteered a series of safety actions during a TSB investigation, the safety culture may not even have achieved the Reactive level routinely. The scale of unreported occurrences and serious incidents uncovered by TSB suggests that the end customer was either not effective at sharing lessons or their contractors were not inclined to draw attention to adverse events. Again this may be because a large non-aviation organisation was dismissing or down playing significant flight safety events that don’t result in injuries and so would not reflect in their occupational health and safety metrics. Alternatively perhaps its contractors, wishing to protect their supplier performance scores, were not sharing the leaning from occurrences as they will be commercially penalised.

A new approach to contracting is vested contracting / vested outscoring a “business model, methodology, mindset and movement for creating highly collaborative business relationships that enable true win-win relationships in which both parties are equally committed to each other’s success”. It also is designed to stop micromanaging suppliers with disproportionate customer ‘shadow organisations’.

The five principles of the vested contracting approach are:

1. Focus on outcomes, not transactions

2. Focus on the WHAT, not the HOW

3. Agree on clearly defined and measurable outcomes

4. Optimize pricing model incentives

5. Governance structure provides insight, not merely oversight

Ultimately the best way to ensure safety is to select competent, well organised and well resourced contractors upfront and that means evaluating more that just the price of tenders, otherwise your assurance activity will be as unsuccessful as King Canute was holding the tide back.

Safety Resources

The European Safety Promotion Network Rotorcraft (ESPN-R) has a helicopter safety discussion group on LinkedIn. You may also find these Aerossurance articles of interest:

- CHIRP Critical of an Oil Company’s Commercial Practices.

- The Tender Trap: SAR and Medevac Contract Design

- Review of “The impact of human factors on pilots’ safety behavior in offshore aviation – Brazil”

- How To Destroy Your Organisation’s Safety Culture

- How To Develop Your Organisation’s Safety Culture

- Challenger Launch Decision – 30 Years On

- Tool Bag Takes Out Tail Rotor: Fatal AS350B2 Accident, Tweed, ON

- Survey Aircraft Fatal Accident: Fatigue, Fuel Mismanagement and Prior Concerns

- HESLO AS350 Fatal Accident Positioning with an Unloaded Long Line

- Short Sling Stings Speedy Squirrel: Tail Rotor Strike Fire-Fighting in Réunion

- Snagged Sling Line Pulled into Main Rotor During HESLO Shutdown

- HESLO EC135 LOC-I & Water Impact: Hook Confusion after Personnel Change

- Garbage Pilot Becomes Electric Hooker (Helitrans AS350B3 LN-OGA)

- Load Lost Due to Misrigged Under Slung Load Control Cable

- Keep Your Eyes on the Hook! Underslung External Load Safety

- EC120 Underslung Load Accident 26 September 2013 – Report

- Unexpected Load: AS350B3 USL / External Cargo Accident in Norway

- Unexpected Load: B407 USL / External Cargo Accident in PNG

- Fallacy of ‘Training Out’ Error: Japanese AS332L1 Dropped Load

- Inadvertent Entry into IMC During Mountaintop HESLO

- HESLO AS350B2 Dropped Load – Phase Out of Spring-Loaded Keepers for Keeperless Hooks

- Unballasted Sling Stings Speedy Squirrel (HESLO in France)

- Dynamic Rollover During HESLO at Gusty Mountain Site

- Fuel Starvation During Powerline HESLO

- HESLO Baffled Attitude Fuel Starvation Accident

- Ditching after Blade Strike During HESLO from a Ship

- The Curious Case of the Missing Shear Pin that Didn’t Shear: A Fatal Powerline Stringing Accident

- HESLO Dynamic Rollover in Alaska

- Windscreen Rain Refraction: Mountain Mine Site HESLO CFIT

- When Habits Kill – Canadian MD500 Accident

- Loss of Control During HESLO Construction Task: BEA Highlight Wellbeing / Personal Readiness

- Shocking Accident: Two Workers Electrocuted During HESLO

- NZ Firefighting AS350 Accident: Role Equipment Design Issues

- Night Mountain Rescue Hoist Training Fatal CFIT

- Whiteout During Avalanche Explosive Placement

- Impatience Comes Before a Fatal Fall During HESLO

- Crashworthiness and a Fiery Frisco US HEMS Accident

- UPDATE 5 August 2023: A Concrete Case of Commercial Pressure: Fatal Swiss HESLO Accident

- UPDATE 6 April 2024: Fatal Fall after HESLO Helicopter Hooks Worker

Airbus has issued several documents to warn of the risks when operating with external loads including Service Letter No 1727-25-05 of 26 March 2006 and Safety Information Note (SIN) No 3170-S-00 of 3 October 2017.

See also: EHEST Leaflet HE7: Techniques for Helicopter Operations in Hilly and Mountainous Terrain

Recent Comments