Impatience Comes Before a Fatal Fall During HESLO (Heliscan Airbus AS350B3 LN-OYH)

On 16 November 2021 Airbus AS350B3 LN-OYH, operated by Heliscan, was involved in a fatal Helicopter External Sling Load (HESLO) accident at Åsäng, in Västernorrland County, Sweden. A member of the ground part got caught by the cargo sling, was lifted into the air and fell.

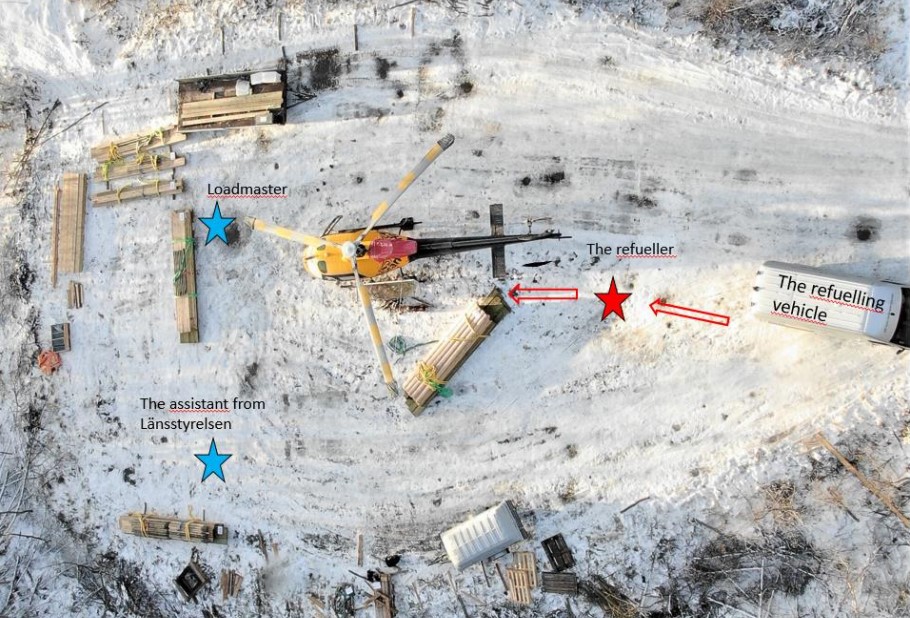

Accident Site: Heliscan Airbus AS350B3 LN-OYH (Credit: Erik Engelro Västernorrland County Administrative Board via SHK)

The Accident

The Swedish Accident Investigation Authority (Statens haverikommission –

SHK) explain in their safety investigation report, issued on 7 November 2022, that…

…Heliscan was transporting timber…on behalf of the Västernorrland County Administrative Board. Heliscan had three people assigned to this job: a pilot, a loadmaster and a refueller.

On the day before the occurrence, final preparations were made at Heliscan in Östersund. At this time, the staff involved went through the job and prepared the equipment.

The refueller (59) was not present at that briefing but was briefed that evening by the pilot (33, with 984 hours of flying experience, 804 on type).

The company’s Ops Manual states that the pilot is ultimately responsible on site for implementation of the task.

Ahead of the job, the [pilot] conducted a final risk assessment on site in accordance with the company’s document Safe Job Analysis.

On the day of the accident:

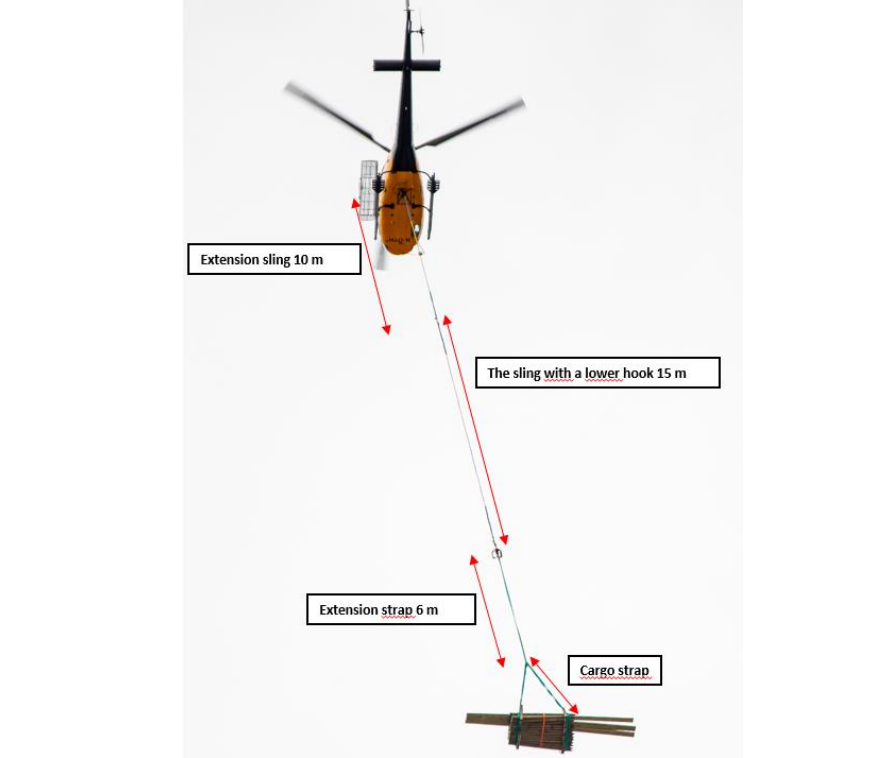

As a result of high surrounding terrain and tall trees, the pilot made the decision to use a 10 m long extension to the sling, which meant that the total length was 25 m.

HESLO Using Heliscan Airbus AS350B3 LN-OYH on the Day of the Accident (Credit: Erik Engelro Västernorrland County Administrative Board via SHK)

In addition, some loads that had to be transported to places that were difficult to access were extended with an extra cargo strap that was 6 m long. These extra straps were attached to the prepared loads of timber using a shackle.

Using…an extension [strap] on certain loads meant that the safe distance to obstructions in certain places was improved. However, the fact that the extension was attached to the load that was on the ground entailed an increased risk of these straps lying free on the ground, which thus increased the risk of becoming caught in them. …no specific risk analysis was conducted in respect of attaching an extra strap to the loads.

We discussed a similar hazard back in 2014: Keep Your Eyes on the Hook! Underslung External Load Safety

The loadmaster was responsible for preparing then loads and had an assistant from Länsstyrelsen. They both had radio contact with the pilot and were meant to be the only people near the load when the helicopter approached. The refueller did not have a radio. This was a conscious decision to minimise distraction radio transmissions.

However, earlier in the day of the accident the refueller had attached loads, despite this not being part of his duties, though he had worked as a loadmaster for another helicopter operator for 30 years. He was not a pilot and Heliscan’s philosophy is that all their loadmasters should be pilots.

The loadmaster and the refueller knew each other well and, prior to the day in question, had spoken several times about how the work would be conducted on site. The loadmaster was concerned that the refueller would not stick to his specific task and would instead step in and work in the high-risk area as well. The loadmaster had repeatedly asked the refueller to simply stick to the refuelling, most recently on the evening before the accident.

Work started on site only extra preparation to make the site suitable (tidying away loose articles) and inspecting the loads.

After these steps had been completed, the refueller told the pilot that the preparations had taken too long and that they need to get started on the job. The pilot pointed out that he had full responsibility for the operation and that the refueller’s only task was to refuel the helicopter.

Once the work got under way, the refueler remained close to the refuelling vehicle and refuelled the helicopter at regular intervals when it came in for landing.

During one shutdown the refueler again complained about the slow pace of the task. SHK explain:

During the afternoon, the refueller, on his own initiative, intervened more and more in the work of attaching the loads to the helicopter. It is documented that on at least one occasion the refueller attached a load and gave the signal to the pilot that it was ready to be lifted. According to the witnesses, this may have occurred one more time during the latter part of the day. The loadmaster…suggested that that [the refueller go have] a cup of coffee in the refuelling vehicle in order to get him to stay out of the loading site.

Also:

Despite the refueller being at the loading site, he did not wear protective equipment in accordance with the company’s manual. The loadmaster had encouraged the refueller to put on protective equipment on at least one occasion. The equipment was available on site but the refueler chose not to use it.

At c15:55, after 23 of the 30 planned loads had been moved the pilot made the decision that as the light was fading, the remaining loads would be moved the next day.

The loadmaster conveyed this decision to the refueller. The refueller then questioned this and insisted that the pilot must continue because people were standing out on the drop sites waiting.

The refueller also said he couldn’t stay locally that night and had to return home.

The loadmaster and the assistant positioned themselves for a landing.

When coming in for landing, the pilot did not see the hook and therefore assumed that it was dragging along the ground. The fogged up rear view mirror may at this point have resulted in the pilot’s view of the hook being restricted. The pilot initiated a climb in order to get the hook in front of himself. The pilot did not see any risk associated with this manoeuvre as he was in contact with the loadmaster and the assistant who were positioned in front of the helicopter.

Personnel Locations at the Accident Site: Heliscan Airbus AS350B3 LN-OYH (Credit: Erik Engelro Västernorrland County Administrative Board via SHK)

Unbeknownst to the pilot, moments before the refueller had “grabbed the cargo hook and attached a load” just before the helicopter gained. This action was a surprise to both loadmaster and assistant and so they were unable to intervene in time.

The refueller got caught in the cargo strap… The loadmaster and the assistant saw the refueller being lifted up into the air and swung round horizontally in the air about five metres above the ground.

…injuries to the fingers of his left hand suggest that his hand got stuck in the hook. The film material and the investigations conducted by SHK also suggest that the refueller was standing in a loop in the strap while attaching the load.

He then fell to the ground a few metres in front and to the left of the helicopter. The refueller was severely injured by the impact and later died.

SHK Analysis & Conclusions

The SHK comment that “misgivings” about the refueller’s behaviour had been voiced before the day of the accident.

…it has been clear that the refueler, despite his extensive experience, did not comply with the instructions and requests he had been given.

One might even consider if the refueller did not comply BECAUSE of his prior experience.

It is also possible to question whether sufficient action had been taken to prevent the situation that arose. It ultimately always falls on the employer to ensure there is a safe work environment by identifying such situations and taking action in order to achieve a functioning group dynamic.

SHK comment that:

It has not been possible to establish the reason why the refueller took hold of the hook and attached a new load. One possible scenario may be that the refueler was doing so in order to forcibly persuade the pilot to continue the day’s work by also flying out this load.

One other possible scenario is that the refueller did not perceive the pilot’s final confirmation of his intention to land and also did not perceive that the loadmaster and assistant had positioned themselves for landing and was therefore mentally prepared for the operation to continue; as he had questioned the pilot’s intention to stop for the day.

Irrespective of the scenario, the refueller may have been so prepared to attach a new load that he consequently underestimated the risk and made an incorrect assessment of the risk of getting hold of the hook and attaching a new load.

Also video footage of the operation…

…showed that people and also the refueller have been moving around and have been standing inside the cargo straps that were lying on the ground before the helicopter lifted the load.

The SHK conclude that:

The cause of the accident was that the refueller, on his own initiative, took hold of the cargo hook on the helicopter and attached a load without the pilot and the loadmaster being aware of this.

The pilot’s adjustment of the height prior to the landing led to the refueller getting caught in the cargo strap and being lifted up into the air.

The actions taken by the pilot and the loadmaster during the work in order to ensure that the refueller acted within the scope of his own duties and that the work could be conducted in a safe manner, have not been sufficient.

Key SHK observations are that:

It is easy in retrospect to see that the obvious action of stopping all work, at least temporarily, should have been taken because the rules of procedure were departed from on several occasions during the day. In summary, it can be concluded that it may be difficult to manage others who have, in comparison, much more extensive experience.

It is a challenge in terms of leadership for a small company or autonomous units to manage members of staff with varied ambitions and experience…

Consequently SHK conclude that:

In the present case, the pilot and the loadmaster had to balance between the company’s safety requirements and alleviating the effect of differing levels of ambition among the individuals on site.

Essentially, this appears to be a question of the composition of the team and how to achieve a functioning group dynamic, which there is reason for the operator to study further.

The findings of the investigation do not however suggest that there were any underlying systemic shortcomings.

Safety Actions

Following the occurrence, Heliscan has, in partnership with Länsstyrelsen, conducted a training programme in two stages with relevant staff from Länsstyrelsen in order to review sling load operations using helicopters. This training programme encompassed both theory and practical exercises with sling loads.

Our Safety Observations (UPDATED 16 Nov 2022)

Firstly its worth remembering that, as common with fatal accidents, the person who died can’t give their version of what happened.

In this case an employee’s prior knowledge, experience and possibly strong self-confidence in their own experience may have all affected their behaviour. However, the SHK explain that prior to the accident the refueller had been proactive in making suggestions, something that is normally, obviously(!), a good thing that should be encouraged. With the benefit of hindsight, in this case, perhaps that was a weak signal of a future threat to group dynamics, especially where there is, for example, a large age gap between the site supervisor (the pilot) and some other employees.

Some may read this case study and opine that traditional safety reporting is ‘the answer’. That is probably optimistic and certainly the SHK avoided a populist knee-jerk response of espousing safety reporting and / or Safety Management Systems. In fact one might imagine that someone like the refueller could have been a prolific author of safety reports themselves, opining how others should do things differently.

In this case developing supervisory skills, continued competency assessment and workforce intervention / stop work strategies are all highly relevant.

Safety Resources

The European Safety Promotion Network Rotorcraft (ESPN-R) has a helicopter safety discussion group on LinkedIn. You may also find these Aerossurance articles of interest:

- What Lies Beneath: The Scope of Safety Investigations

- Snagged Sling Line Pulled into Main Rotor During HESLO Shutdown

- Garbage Pilot Becomes Electric Hooker (Helitrans AS350B3 LN-OGA)

- Load Lost Due to Misrigged Under Slung Load Control Cable

- Keep Your Eyes on the Hook! Underslung External Load Safety

- EC120 Underslung Load Accident 26 September 2013 – Report

- Unexpected Load: AS350B3 USL / External Cargo Accident in Norway

- Unexpected Load: B407 USL / External Cargo Accident in PNG

- Fallacy of ‘Training Out’ Error: Japanese AS332L1 Dropped Load

- Inadvertent Entry into IMC During Mountaintop HESLO

- HESLO AS350B2 Dropped Load – Phase Out of Spring-Loaded Keepers for Keeperless Hooks

- Unballasted Sling Stings Speedy Squirrel (HESLO in France)

- Dynamic Rollover During HESLO at Gusty Mountain Site

- Fuel Starvation During Powerline HESLO

- HESLO Baffled Attitude Fuel Starvation Accident (Haverfield Aviation Hughes 369E N765KV)

- Running on Fumes: Fatal Canadian Helicopter Accident

- UH-1H Fuel Exhaustion Accident

- Ditching after Blade Strike During HESLO from a Ship

- The Curious Case of the Missing Shear Pin that Didn’t Shear: A Fatal Powerline Stringing Accident

- HESLO Dynamic Rollover in Alaska

- Windscreen Rain Refraction: Mountain Mine Site HESLO CFIT

- When Habits Kill – Canadian MD500 Accident

- Loss of Control During HESLO Construction Task: BEA Highlight Wellbeing / Personal Readiness

- Shocking Accident: Two Workers Electrocuted During HESLO

- UPDATE 19 November 2022: Whiteout During Avalanche Explosive Placement

- UPDATE 26 November 2022: Guarding Against a Hoist Cable Cut

- UPDATE 1 January 2023: HESLO EC135 LOC-I & Water Impact: Hook Confusion after Personnel Change

- UPDATE 18 March 2023: HESLO AS350 Fatal Accident Positioning with an Unloaded Long Line

- UPDATE 5 August 2023: A Concrete Case of Commercial Pressure: Fatal Swiss HESLO Accident

- UPDATE 6 April 2024: Fatal Fall after HESLO Helicopter Hooks Worker

See: UK CAA‘s CAP 426: Helicopter External Load Operations too.

Final Word

A public inquiry chaired by Anthony Hidden QC investigated 1988 Clapham Junction rail accident. In the report of the investigation, known as the Hidden Report, he commented:

There is almost no human action or decision that cannot be made to look flawed and less sensible in the misleading light of hindsight. It is essential that the critic should keep himself constantly aware of that fact.

Recent Comments