EC130B4 Accident: Incorrect TRDS Bearing Installation

The Accident Investigation Board Norway (AIBN) has recently reported on a serious incident involving Airbus Helicopters EC130B4 LN-ORR, operated by Helicopter Utleie (now trading as Fjord Helikopter) on 12 August 2014 when arriving at Rørvik Airport for refuelling.

The Incident

As the helicopter passed over the runway threshold at about 15-30 feet the helicopter started to yaw to the left:

The commander quickly understood that he had no directional control, and chose to land the helicopter without engine power. The helicopter rotated twice around its own axis before it was landed on the runway. No injuries or damage occurred.

AIBN say:

The reason it did not have more serious consequences was because the commander quickly figured out that the tail rotor was not functioning, and he made the right decisions.

…it was decisive for the outcome that the incident occurred over a flat surface.

Had the tail rotor shaft fracture occurred at a less favourable moment, and over rugged terrain, the outcome of the incident could have been fatal.

The Technical Investigation and Analysis

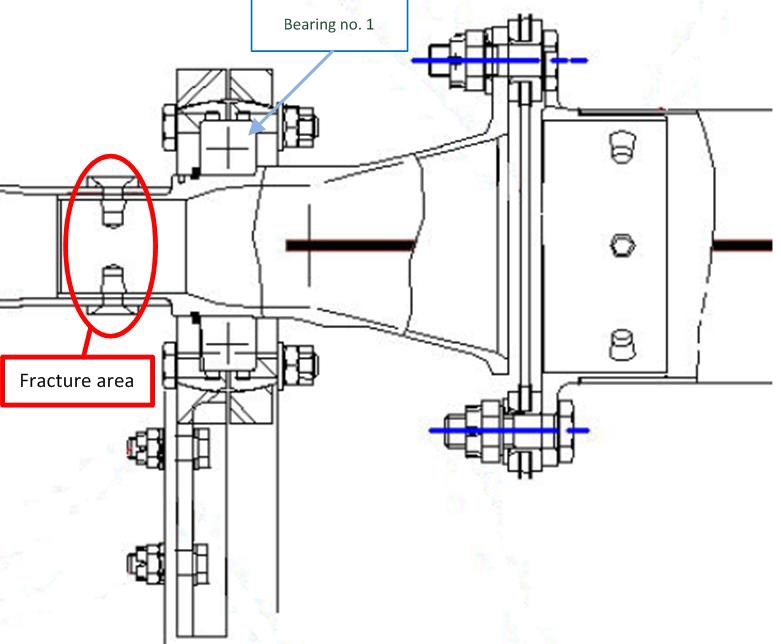

An examination revealed that the riveted joint just behind the tail rotor drive shaft (TRDS) no. 1 bearing had fractured.

The bearings on the TRDS had been replaced during scheduled maintenance 98 flying hours prior to the incident. AIBN say:

It became evident that the position of the bearing in relation to the shaft did not comply with the Aircraft Maintenance Manual (AMM) requirements. The measured discrepancy was approximately 1 millimetre, whereas the maximum permitted value in the AMM is 0.1 millimetre.

Lab examination showed the rivet holes had deformed and the six rivets had become worn over time.

When the rivets came loose gradually, the load increased to such a point that fatigue fractures occurred in some of the rivet holes on the shaft. There were also signs of a ductile fracture in one of the rivet holes.

Lab examination of the bearing “showed that the bearings balls had made an abnormal track in the outer race”.

AIBN asked the technician who installed the bearing to demonstrate the measurement method for verifying the bearing’s position in “Bearing drive/Bearing flange”. The measurement demonstrated to AIBN did not comply with the method described in the helicopter’s AMM.

The aircraft technician had worked alone on Helikopter Utleie’s helicopters for many years. Without having a community of colleagues for support, there may be a risk of developing sub-standard working methods.

The technician, from a contracted Part 145 (see below), had incorrectly used the tailboom structure as the reference not the TRDS itself. The AIBN state the specific AMM task was “was fully understandable”. With condor and proactivity:

Airbus Helicopters… concluded that the measuring method and adapter to attach the dial gauge to the tail rotor shaft should be emphasised more clearly in AMM, so there is a greater degree of reproducibility of the measurement results when replacing bearing no. 1.

AIBN established that the bearing installation had not been subject to an Independent Inspection by a second person.

The work on LN-ORR was carried out at the helicopter company base in Stryn. The technician carried out this work alone. In a best case scenario, he would have inspected his own work. This would have been an inspection based on his personal understanding of the procedure in AMM, which was incorrect as regards installation of bearing no. 1.

An independent inspection performed by another competent person could have identified the error.

The aircraft technician is at “the sharp end”, where errors can have direct consequences for flight safety. The AIBN is therefore of the opinion that having just one person carry out maintenance tasks that qualify as “Flight Safety Sensitive Maintenance Tasks” or “Complex Maintenance Tasks” alone should be avoided.

The AIBN also noted that the maintenance organisation “did not split up and specify the work in their worksheets for ‘Complex Maintenance Tasks’ as described in EASA Part 145”. The lack of such stage sheets has been observed in other accident investigations (e.g. this NTSB investigation Fatal $16 Million Maintenance Errors).

Organisational and Regulatory Information

At the time of the incident the operator had a fleet of two EC130B4 and one EC120B. Being as small operator the Accountable Manager was also the Quality Manager. Further, the the Continuing Airworthiness Post-holder was a part time contractor. The company had placed a contract with a large Part 145 approved maintenance organisation SAM Aero. AIBN say that their investigation resulted in the:

…impression that certificates and governing documents from both the helicopter company and the maintenance organisation were adequate.

However:

The fact that good intentions and formulations were not always followed, first emerged in connection with investigation surrounding the actual incident.

AIBN say:

At the time of the serious incident involving LN-ORR, the company had privileges to perform maintenance on AS350 series, EC130B4 and EC120B helicopters. This service was only performed for Helikopter Utleie AS. Following the incident with LN-ORR, the Norwegian Civil Aviation Authority [CAA-NO] conducted an extraordinary audit of the company. The company’s A3 (Helicopter) privileges were withdrawn based on findings during the audit.

The issues identified by the CAA-NO included:

- Difference in definition of requirements for inspection of maintenance work in both the operating company and maintenance organisation.

- Inadequate planning of maintenance tasks, both as regards specifying the work, and facilitation with regard to tools.

- Both Helikopter Utleie AS and SAM Aero accepted that one person was conducting all maintenance alone on the helicopters.

- The use of the combination of contracted maintenance organisations performing maintenance and contracted responsible personnel can be challenging for the operating company regarding supervision of the maintenance processes.

The AIBN discuss enhancements to EASA Part 145 and Part M (NPA 2012-04) that we have previously written about (Critical Maintenance Tasks: EASA Part-M & -145 Change). They also note that EASA completed a “Standardisation Inspection” of the Norwegian CAA in June 2014, and made a finding that:

The CAA-NO does not ensure that the requirement for independent inspections as specified in M.A.402(a) is applied in maintenance organisations. Substantiation: Both Part-145.A.65(b)(3) ‘capture errors on critical systems’ and M.A.402(a) ‘flight safety sensitive maintenance tasks’, require methods to control maintenance errors that could endanger the safe operation of an aircraft if not performed properly. Independent inspections are required to capture these ‘safety related’ errors according to M.A.402(a) and these should be carried out by at least two persons (the second person not necessarily CS, but at least appropriately qualified to perform the task), UNLESS otherwise specified by Part 145 or agreed by the competent authority.

AIBN comment:

Based on the EASA inspection, the Norwegian CAA has dedicated more focus on what the organisations do to prevent maintenance errors when performing audits. The AIBN considers this change a good contribution to flight safety.

In late 2015 the NCAA issued a presentation on Independent Inspections.

EASA has previously noted that in NPA 2012-04:

A re-inspection as an error capturing method should only be used in unforeseen circumstances when only one person is available to carry out the task and perform the independent inspection. The circumstances cannot be considered unforeseen if the organisation has not programmed a suitable “independent qualified person” onto that particular line station or shift.

Re-inspection of ones own work has “traditionally been a common practice in this part of Norwegian aviation” say AIBN (also see pages 145 and 162 of Helicopter Safety Study 3 [HSS3] were the value of a stricter regime was ranked ‘low’). AIBN says that implementation of NPA 2012-04 (via Commission Regulation (EU) 2015/1536) from 25 August 2016 “will help to reduce the maintenance error risk, particularly in small organisations with marginal resources and staffing”.

The AIBN go on to summarise the safety responsibilities of key parties:

- The technician is responsible for executing maintenance in accordance with the manufacturer’s maintenance instructions, described maintenance programme from the operator (Part M [CAMO]), competence and sound technical judgement.

- Both the operating company [CAMO] and maintenance organisation are responsible for describing the planned maintenance tasks precisely and clearly.

- The helicopter manufacturer is responsible for describing the individual helicopter maintenance tasks in an understandable and precise manner.

- Through audits, the Norwegian Civil Aviation Authority shall ensure that the involved parties perform maintenance in accordance with regulations.

- EASA must ensure that their regulations are clear and comprehensive.

Our Observations

Aerossurance has previously written about several accidents and incidents that could have been prevented by an Independent Inspection:

- Critical Maintenance Tasks: EASA Part-M & -145 Change

- Fatal $16 Million Maintenance Errors

- Loose B-Nut: Accident During Helicopter Maintenance Check Flight

- USAF RC-135V Rivet Joint Oxygen Fire

- The Missing Igniters: Fatigue & Management of Change Shortcomings

- Misassembled Anti-Torque Pedals Cause EC135 Accident

Some of the lessons regarding lone workers doing complex maintenance tasks are reinforced by the UK Air Accident Investigation Branch (AAIB) report into the loss of tail rotor pitch control on a police AS355F2 G-SAEW on 21 April 2000 in Cardiff, UK.

UPDATE: Discussion on the European Helicopter Safety Team (EHEST) European Helicopter Safety LinkedIn Group rapidly highlighted another relevant report, that of the Swedish Accident Investigation Authority (SHK) report into the lost of tail rotor drive on AS350B3 SE-JKF in 2009 at Stockholm/Arlanda airport.

Safety Resources

Aerossurance worked with the Flight Safety Foundation (FSF) to create a Maintenance Observation Program (MOP) requirement for their contractible BARSOHO offshore helicopter Safety Performance Requirements to help learning about routine maintenance and then to initiate safety improvements:

Aerossurance can provide practice guidance and specialist support to successfully implement a MOP.

An excellent initiative to create more Human Centred Design (HCD) by use of a Human Hazard Analysis (HHA) is described in Designing out human error

HeliOffshore, the global safety-focused organisation for the offshore helicopter industry, is exploring a fresh approach to reducing safety risk from aircraft maintenance. Recent trials with Airbus Helicopters and HeliOne show that this new direction has promise. The approach is based on an analysis of the aircraft design to identify where ‘error proofing’ features or other mitigations are most needed to support the maintenance engineer during critical maintenance tasks.

Aerossurance has previously written these more general articles:

- Professor James Reason’s 12 Principles of Error Management

- How To Develop Your Organisation’s Safety Culture

- Maintenance Human Factors: The Next Generation

- Aircraft Maintenance: Going for Gold?

UPDATE 11 July 2016: EASA publish ED Decision 2016/011/R (Acceptable Means of Compliance and Guidance Material to Annex I (Part-M), Annex II (Part-145), Annex III (Part-66) and Annex Va (Part-T) to Commission Regulation (EU) No 1321/2014)

UPDATE 12 February 2017: Flying Control FOD: Screwdriver Found in C208 Controls

UPDATE 26 March 2017: Cessna 208 Forced Landing: Engine Failure Due To Re-Assembly Error

UPDATE 16 April 2017: Insecure Pitch Link Fatal R44 Accident

UPDATE 23 February 2018: NTSB Reveal Lax Maintenance Standards in Honolulu Helicopter Accident

UPDATE 19 May 2018: If you had spent 2 years rebuilding a classic Piper PA-12 you’d make the time to check the rigging of the flying controls before first flight, right? Sadly, the pilot in this fatal case study was in a rush: Too Rushed to Check: Misrigged Flying Controls

UPDATE 24 June 2018: B1900D Emergency Landing: Maintenance Standards & Practices The TSB report posses many questions on the management and oversight of aircraft maintenance, competency and maintenance standards & practices after this serious incident. We look at opportunities for forward thinking MROs to improve their maintenance standards and practices.

UPDATE 25 August 2018: Crossed Cables: Colgan Air B1900D N240CJ Maintenance Error On 26 August 2003 a B1900D crashed on take off after errors during flying control maintenance. We look at the maintenance human factor safety lessons from this and another B1900 accident that year.

UPDATE 9 May 2020: Ungreased Japanese AS332L Tail Rotor Fatally Failed

UPDATE 5 September 2020: SAR AS365N3 Flying Control Disconnect: BFU Investigation

UPDATE 8 January 2022: Fiery Fatal AW119 Accident in Russia After Loss of Tail Rotor Control

UPDATE 25 May 2025: CHC Sikorsky S-92A Seat Slide Surprise(s)

Aerossurance is pleased to sponsor the 2017 European Society of Air Safety Investigators (ESASI) 8th Regional Seminar in Ljubljana, Slovenia on 19 and 20 April 2017. Registration is just €100 per delegate. To register for the seminar please follow this link. ESASI is the European chapter of the International Society of Air Safety Investigators (ISASI).

Aerossurance sponsored an RAeS HFG:E conference at Cranfield University on 9 May 2017, on the topic of Staying Alert: Managing Fatigue in Maintenance.

Aerossurance is pleased to be both sponsoring and presenting at a Royal Aeronautical Society (RAeS) Human Factors Group: Engineering seminar Maintenance Error: Are we learning? to be held on 9 May 2019 at Cranfield University.

Recent Comments