Yuma Hawk Accident: Lessons on Ex-Military Aircraft Operation

A fatal accident with an ex-Korean Hawk, operated by a defence contractor, highlights some of the issues of civil use of ex-military aircraft. On 11 March 2015, the BAe Hawk Mk 67 (known in Korea as a T-59), N506XX, operated by Air USA, struck a vehicle after a stall during take off at the joint military / civil airfield at Yuma, AZ. The driver of the vehicle died in the crash. The two occupants of the Hawk (pilot and passenger) were not injured but the aircraft was destroyed by fire.

The Republic of Korea Air Force (ROKAF) had ordered 20 Hawk Mk67s in July 1991. They were retired in 2013 with Air USA purchasing 12. The aircraft had an Experimental Certificate of Airworthiness and was being operated as a Public Aircraft (effectively the FAA equivalent of a civil ‘State Aircraft’, to use ICAO terminology), on contract to the US Air Force (USAF) in support of a Special Operations Terminal Attack Controller Course (SOTACC).

The Accident Flight and the Aircraft Configuration

The US National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) in their investigation report, explain N506XX was one of a pair performing a 15-second staggered takeoff from runway 03L, to provide close air support for the training of Joint Terminal Attack Controllers (JTAC‘s). It was equipped with external fuel tanks on the inboard wing pylons, and SUU-20 Bomb Dispenser/Rocket Launchers (on loan from the USAF), loaded with practice ordinance, on the outboard pylons. The NTSB comment:

The external fuel tanks were partially filled with fuel, which was allowed per the airplane’s flight manual… The SUU-20 had not been evaluated by BAe and was not listed as an approved device in the Hawk Weapons Manual, and as such in April 2014, Air USA commissioned an FAA Designated Engineering Representative (DER) to prepare a structural comparison report to assess the viability of installing the SUU-20, along with a series of other non-BAe evaluated munitions and stores. The report utilized the comparative dimensions of the CBLS-200, MK-83 free fall bomb, and the fuel tank. The MK-83 was nearly identical in length to the SUU-20, and weighed 987 pounds. Any intended use of the fuel tank as a basis for comparison was erroneous, as the tank was not capable of being fitted to the outboard pylon. The report was structural only in nature, and did not take into account the aerodynamic effects of utilizing the alternate munitions and stores. The report concluded that the use of the alternate stores was, “structurally satisfactory.” It is possible that the airplane’s stall margin was eroded further by the use of the alternate dispensers…

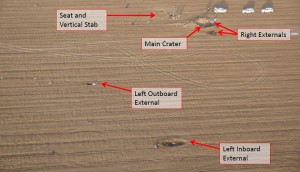

The NTSB say that the pilot was “unable to maintain airplane control following rotation. The airplane did not climb, departed the left side of the runway, and struck a pickup truck”. A United States Marine Corps (USMC) construction crew was next to runway 03L preparing for the installation of an expeditionary arresting gear system (as shown below in use in the Pacific): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gxzzmtbcOec The NTSB say:

The pad was located 10 feet from the runway edge, about 6,500 feet from the runway 03L landing threshold. The construction operation, which included support vehicles, crew, and construction equipment, occupied the space from the runway pad outwards about 150 feet. The truck that was struck was located 140 feet beyond the runway edge, and was occupied by a Marine Lance Corporal who was providing operational escort and safety support for the construction crew.

The NTSB go on:

The entire accident sequence was captured by an onboard video camera, which was positioned inside the canopy at the rear of the cockpit. The camera recorded some engine instruments, the primary flight instruments, the back of the pilot’s head, and the runway and horizon. Analysis of the recording revealed that the pilot initiated rotation about 8 knots before reaching the correct indicated airspeed and that the airplane lifted off the ground about 10 knots early, about the same time as it reached its target pitch attitude. The video image, which up until this point had been smooth, then began to shudder in a manner consistent with the airplane experiencing the buffet of an aerodynamic stall. The airplane immediately rolled aggressively left, and the main landing gear struck the ground hard. The airplane then pitched up aggressively and began a series of roll-and-pitch oscillations, bouncing from left to right with the outboard bomb dispensers and landing gear alternately striking the ground as the pilot attempted to establish control. The airplane passed beyond the runway edge and reached its target takeoff speed just before striking the truck, but by this time, it had departed controlled flight, was in a steep right bank at almost twice its target pitch attitude, indicating that it had likely aerodynamically stalled.

The pilot was a current reserve A-10 pilot, who had gained all his Hawk experience at Air USA, commencing training in August 2014, that comprised of:

…flight manual study, followed by 2 days of ground school, cockpit familiarization, and ejection seat training. He then flew three graded instructional flights including five cross-country flights…after which he was cleared to take the checkride for type rating with an FAA Designated Pilot Examiner [DPE]…went on to receive further [mission related] instruction…and after about 12 hours of total flight time, he was approved by Air USA to fly solo missions. Air USA was the only private operator of the Hawk in the United States, and as such, the FAA DPE who performed the pilot type rating checkride did not have direct experience flying the Hawk. The pilot reported that he felt the airplane’s nose become light as the airplane approached rotation speed, and the video revealed that the nose was oscillating lightly up and down a few seconds before rotation, consistent with his statement. The pilot stated that, before takeoff, he set the pitch trim to 3 degrees nose up, which was consistent with the operator’s policy for takeoff with external stores. The policy was in place to relieve stick pressure on rotation; however, the airplane’s flight manual specified that 0 degrees pitch trim should be used for takeoff in all configurations. During the postaccident examination, the airplane’s pitch trim was found at almost full nose up for reasons that could not be determined.

The NTSB concluded:

It is likely that the pilot initiated an early rotation instinctively as the airplane’s nose became light due to the excessive nose-up pitch trim. The operator stated that the company policy for nose-up trim on takeoff was intended to give the airplane control stick pressures on rotation comparable to other U.S. fighter aircraft, such as the FA-18 and F-16. Although the operator had used this technique without incident on many prior missions, it was in direct contrast with the manufacturer’s takeoff recommendations and likely increased the risk of early rotation.

Airworthiness Support

As the Hawk (though not the Mk67) was still being manufactured Air USA rashly “presumed that OEM support would be available”. However, it is normal for manufacturers of military aircraft only to support the original customer and they have no obligation to support any subsequent civil customers unless a specific support contract is agreed:

Air USA was granted a series of interim flight clearances for the Hawk from NAVAIR valid through January 31, 2016, with the understanding that beyond that period OEM support had to be achieved, along with reach back support. BAe reported that they initially received a request for support from Air USA on September 2, 2014, and replied stating that they did not support the continued operation of the Hawk by Air USA… BAe provided technical assistance to the NTSB during that accident investigation, and at the time of publication of this report, their decision to not provide support to Air USA remained in effect. Air USA voluntarily ceased Hawk operations immediately following the accident, instead supporting the current USAF contract with their fleet of L-39 airplanes. Following completion of the initial phase of the investigation, Air USA restarted Hawk operations on April 20, as part of a live CAS support mission for the USAF. At the time of the accident maintenance was being performed utilizing OEM replacement components, which were acquired from the ROKAF during the initial sale of the airplanes.

It is not clear how air USA intended to replace shelf-life limited parts, such as ejection seat pyrotechnics (an issue identified by a UK Air Accidents Investigation Branch [AAIB] investigation into an air display accident involving Hawker Hunter TMk7 G-BXFI at Shoreham in 2015).

Regulation and Oversight

The NTSB say:

About 21 months before the accident, the DoD issued a directive that all aircraft owned, leased, operated, used, designed, or modified by DoD must have undergone an airworthiness assessment in accordance with the applicable military department policy and that management authorities within the military departments should be established to provide ongoing oversight. The directive allowed the use of DoD or FAA airworthiness certification standards. Under the auspices of this directive, the operator had undergone a series of oversight inspections from the Naval Air Systems Command and interim flight clearance was granted to perform missions for the USMC. Although the accident flight departed from a USMC base, it was operating in support of the USAF, and the USAF chose to place the responsibility of certification and ongoing oversight with the FAA. However, because the airplane’s missions were flown under the umbrella of “public aircraft,” the FAA was not providing, nor was it required to provide, any oversight beyond issuance of the airplane’s initial airworthiness certificate. As such, the operator was effectively operating without oversight at the time of the accident. This lack of oversight likely enabled the continued operating philosophy, which resulted in the difference in takeoff procedure between the operator and the manufacturer and the use of inadequately evaluated weapons system components. Air USA voluntarily ceased Hawk operations immediately following the accident, instead supporting the current USAF contract with their fleet of L-39 airplanes. Following completion of the initial phase of the investigation, Air USA restarted Hawk operations on April 20, as part of a live CAS support mission for the USAF. The USAF continued to utilize Air USA for close air support missions until the contract expired in September 2015. NAVAIR immediately withdrew Air USA’s flight clearance following the accident, a decision which remained in effect at the time of this report’s publication. The USAF continued to utilize Air USA for close air support missions until the contract expired in September 2015. On November 9, 2015, the USAF issued a memorandum directing that all Major Commands immediately cease conducting live contracted close air support (CCAS) missions. The memorandum stated that the prohibition would stay in effect pending a review of contract, airworthiness, and aircrew training related to the missions, and that the goal was to ensure that the relevant contracts adequately protected public interests. This prohibition remained in effect at the time of this reports publication.

Airfield Safety

The NTSB explain that the majority of the airfield was operated and governed by the Department of Defense (DoD), specifically the USMC, and that since 1956:

It was operated as a “shared use” airport concurrently supporting both military and civilian operations, although the accident runway was used almost exclusively for military flights. USMC airport-specific station orders did not prohibit construction activities in this area, and no notice to airmen relating to construction was issued at the time of the accident nor was one required. If the airport had been under operating under Part 139 regulations and full FAA oversight, no such construction activities would have been permitted while the runway was active, and the ground fatality would have been avoided.

NTSB Probable Cause

In their report, the NTSB determined the probable cause to be:

The pilot’s initiation of an early rotation during takeoff, which led to an aerodynamic stall and loss of airplane control. Contributing to the accident were the pilot’s use of nose up pitch trim and the operator’s policy to use nose-up pitch trim during takeoff and the lack of oversight of the operator by the US Air Force. Contributing to the severity of the accident were US Marine Corps airport policies that allowed construction activities immediately adjacent to an active runway, which resulted in the airplane’s collision with a truck.

Our Observations

The use of ex-military aircraft for contracted training purposes (including JTAC training, Dissimilar Air Combat [DAC] or aggressor training and target towing) as well as to support trials is increasing in several countries as defence budgets shrink and the costs of operating front-line aircraft for these tasks increase. The operator’s experience of this type was low, the conversion course basic and the FAA DPE had no experience on type. The NTSB also report:

On October 18, 2014, an Air USA Hawk, N509XX, was involved in an accident after it departed the runway during the ground roll, just prior to takeoff (NTSB accident number CEN15TA019). The pilot reported that having reached about 90 knots, the airplane turned hard left, and he was unable to regain directional control. Subsequent examination did not reveal any mechanical anomalies to account for the turn, and the NTSB issued the probable cause, “Loss of directional control during the takeoff roll for reasons that could not be determined during post-accident examinations and testing.”

Air USA did not have a support contract in place with the aircraft OEM (nor presumably with the engine OEM), who had declined to support the use of an ex-military type with Air USA. N506XX was:

- Being flown to a company procedure that was outside its flight manual recommendations

- Fitted with modifications that were incompletely assessed (as the operator had not commissioned an aerodynamic analysis of the SUU-20 Bomb Dispenser, which differed in shape substantially from the BAe cleared CBLS-200, nor it seems was any integration testing on the dropping of the practice munitions conducted).

The aircraft was also suffering from on-going fuel system issues. While not a contributory factor in the accident, this perhaps question the organisation’s competence in maintaining this type. Regulatory oversight was minimal (noticeably so when compared to the rigorous UK Military Aviation Authority [MAA] oversight under the Contractor Flying Approved Organization Scheme [CFAOS]).

UPDATE 18 August 2016: An A-4 Skyhawk, operated by Draken International and on contract to USAF, crashed outside Nellis AFB, NV during a Red Flag exercise. (UPDATE 30 June 2020: 17 Year Old FOD and a TA-4K Ejection)

UPDATE 29 August 2016: The NTSB has just published their probable cause of a 2012 Hunter accident:

On May 18, 2012, at 1212 Pacific standard time, a Hawker Hunter Mk 58, single-seat turbojet fighter aircraft, N329AX, operated by ATAC (Airborne Tactical Advantage Company) under contract to Naval Air Systems Command (NAVAIR) crashed while on approach to Naval Air Station Point Mugu, California (NTD). The sole pilot aboard was killed, and the airplane was destroyed by impact forces.

The flight was conducted under the provisions of a contract between ATAC and the U.S. Navy to provide ATAC owned and operated aircraft to support adversary and electronic warfare training with VMFAT-101 (Marine Fighter Attack Training Squadron 101). The airplane was operating as a non-military public aircraft under the provisions of Title 49 of the United States Code Sections 40102 and 40125. ATAC did not have a crew resource management or aeronautical decision making training program in effect. If such a program had been in effect, it may have led the accident pilot to follow the flight lead’s recommendation and return or divert rather than continue the flight and troubleshoot [when a fuel imbalance was first suspected]. The pilot’s decision to continue the flight with a known fuel imbalance is a possible indicator of company culture of pressing to complete the assigned mission. On March 6, 2012 another ATAC fighter crashed, fatally injuring the pilot. In that accident the pilot was also likely pressing to complete the mission, leading eventually to the accident. Following a recommendation in a Navy audit in June 2012, CRM training was established. Also, ATAC established an operational risk management (ORM) program in August 2012. Two days prior to the accident, ATAC maintenance replaced left fuel transfer valve assembly. The mechanic that conducted the work had never performed this task and expressed difficulty and confusion with completing it and had to request assistance from other personnel. No type-specific maintenance training exists for the Hunter and all maintenance training is conducted on-the-job. Although ATAC did have the appropriate manuals on hand to guide the replacement, the maintenance personnel were not aware that they had the British manuals, and only referenced the Swiss French-language manuals, which they could not translate. No task cards, detailed step-by-step instructions for maintenance tasks, existed for the Hunter due to the legacy nature of the aircraft.

The National Transportation Safety Board determines the probable cause(s) of this accident as follows: the pilot’s decision to continue the flight with a known fuel imbalance condition that resulted in a loss of lateral control when the imbalance exceeded the known capabilities of the airplane. The fuel imbalance was due to incomplete refueling and an ineffective preflight inspection by the pilot. The imbalance was further complicated by an incorrectly assembled fuel transfer valve and motor combination. Contributing to the severity of the accident was the pilot’s delayed decision to eject prior to exceeding the ejection seat envelope. Also contributing to the accident was: (1) the Navy’s oversight environment, which did not require airman, aircraft, and risk management controls or standards expected of a commercial civil aviation operation, and (2) ATAC’s organizational environment, which did not include CRM training to promote good aeronautical decision-making and ORM guidance to mitigate hazards. Also contributing to the accident were the design features of the airplane, which were typical of its generation, including the lack of accurate fuel quantity indications, the design of the fuel transfer valve; and the maintenance program’s lack of clearly documented procedures and type-specific training for the Hunter.

The NTSB investigation into the fatal loss of another ATAC Hunter Mk58, N332AX on 29 October 2014 is still underway.

UPDATE 12 April 2017: The NTSB have now issued their probable cause on the 29 October 2014 ATAC Hunter Mk58 N332AX accident:

The pilot’s failure to maintain adequate airspeed during the approach for landing, which resulted in the airplane exceeding its critical angle of attack and experiencing an aerodynamic stall/spin at an altitude too low for recovery.

The purpose of the flight was to support adversary and electronic warfare training with a US Navy, Carrier Strike Group. The NTSB report:

…the 45-year-old pilot held an airline transport pilot certificate [and] had a total flight time of 3,727.1 hours, with an estimated 15.1 hours in the accident airplane make and model. The pilot was recently retired from the United States Air Force after serving 21 years… and was current in the F-16. The pilot was hired by ATAC on September 22, 2014, started his initial training on September 23, 2014, and completed it on October 7, 2014. The pilot then reported to ATAC at Point Mugu to begin his operational training.

The accident flight was the pilot’s 5th flight with ATAC since reporting from his initial training. The pilot flew one mission on October 28 totalling 1.8 hours. On October 26, the pilot flew two missions totalling 3.7 hours. On October 23, the pilot flew one mission totalling 1.8 hours. The pilot had previously flown one overhead break approach prior to the accident flight.

UPDATE 22 August 2017: ATAC lose another Hunter at sea. The pilot is recovered safely. UPDATE 18 April 2020: Jest11 is Dead: Hawker Hunter Downed by F-35A Jet Wash

UPDATE 10 November 2018: The UK MAA comment on the regulation of such operations.

UPDATE 17 November 2018: Investigation into F-22A Take Off Accident Highlights a Cultural Issue another case of early rotation

UPDATE 13 December 2018: And another ATAC Hunter accident occurs and the pilot ejects.

UPDATE 26 July 2019: Usage Related Ex-Military Helicopter Accident

UPDATE 30 June 2020: 17 Year Old FOD and a TA-4K Ejection

UPDATE 22 April 2023: Swinging Snorkel Sikorsky Smash: Structural Stress Slip-up

Recent Comments