AAR Bell 214ST N5748M Accident in Afghanistan in 2012: NTSB Report

On 16 January 2012, Bell 214ST N5748M, crashed 7 miles south of Camp Bastion in Helmand province, Afghanistan, killing the crew of three. The helicopter was operated as a Part 135 flight by AAR Airlift Group under contract to the Department of Defense (DOD) Air Mobility Command (AMC), the air component of the US Transportation Command).

The Accident Flight

The helicopter, call sign ‘Slingshot 72’, was transporting military personnel between coalition bases with another 214ST (N391AL, ‘Slingshot 71’). About 1040, both helicopters departed Camp Bastion after a rotors running turnaround for Shindand Air Base on their third sector of the day. The only passengers were on Slingshot 71. They climbed to a cruising altitude of 800 – 1,000 ft. Slingshot 72 was the lead helicopter, with Slingshot 71 trailing by about ¼ to ½ mile.

The US National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), who were delegated the investigation by the Afghan Ministry of Transport and Civil Aviation, say in their safety investigation report:

The SIC of Slingshot 71, who was the pilot flying, saw Slingshot 72 enter a “sharp” bank to the right; he estimated that the bank was about 70º to 80º. The SIC then saw Slingshot 72 begin to “come apart.” …he flew Slingshot 71 to the left to avoid the large amount of debris coming from Slingshot 72, which included large pieces of structure.

The SIC reported that the tailboom of Slingshot 72 began to “separate and fold” and estimated that about two-thirds of the tailboom came off the helicopter. The SIC then saw Slingshot 72 pitch down about 75º to 80º, impact the ground, and burst into flames.

The PIC of Slingshot 71, who was the pilot monitoring, stated that, after making a radio frequency change, he looked up and saw Slingshot 72 in a “steep pitch down.” The PIC stated that “nothing seemed wrong” with Slingshot 72 when he had looked down to make the radio frequency change. [H]e saw structure starting to come off Slingshot 72 and that the debris looked similar to “confetti.” The PIC noticed that the tailboom of Slingshot 72 appeared to be folded under the helicopter and stated that he could see the “zinc’ color of the inside of the tailboom. Afterward, the PIC observed Slingshot 72 descend “straight down,” impact the ground, and burst into flames. The PIC reported that the flight crew of Slingshot 72 made no radio transmissions indicating any problems.

After US forces reached the area and secured the accident site, Slingshot 71 departed the area and landed uneventfully at Camp Bastion. The Slingshot 72 wreckage was then recovered and moved to a secure location at Camp Bastion.

NTSB Safety Investigation

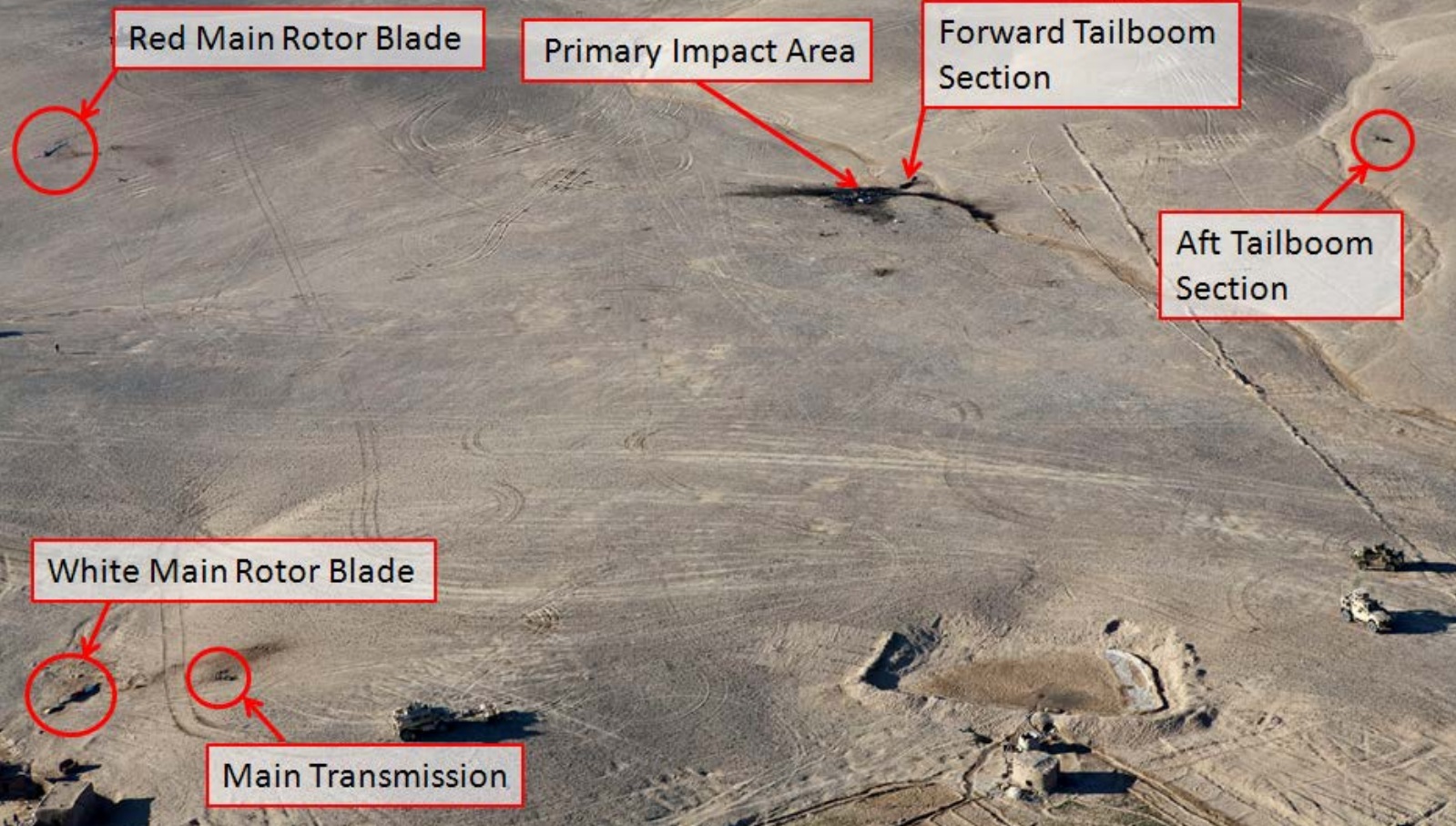

The accident site consisted of a primary impact area and a scattered debris field, which measured about 1,575 feet north-south by 656 feet east-west.

The primary impact area consisted of the main fuselage, which had been fully consumed by the postcrash fire. The forward tailboom section was found separated from the main fuselage about 49 feet north of the primary impact area, and the aft tailboom section (containing the vertical stabilizer and tail rotor) was found about 279 feet north of the primary impact area.

The main debris field was located south of the primary impact area (distance unknown) and included an engine cowling, a door, and one of the two main rotor blades. The other main rotor blade was found about 426 feet southwest of the primary impact area.

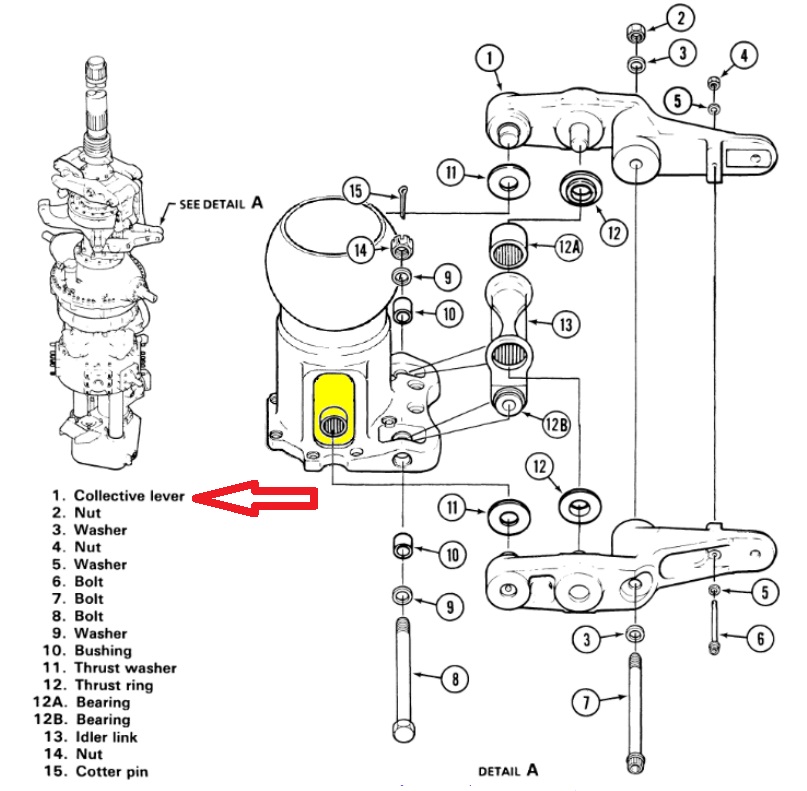

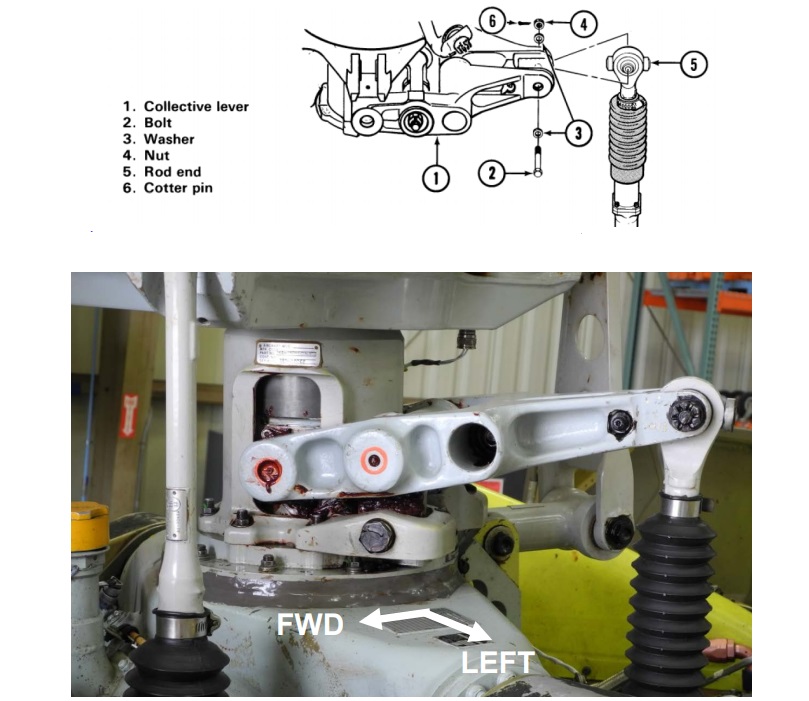

Examination of the wreckage found that only one of the two collective lever arms (subsequently identified as the right collective lever arm) was recovered from the accident site.

Also, the areas on the main transmission’s main rotor mast where the missing (left) collective lever arm was installed did not exhibit damage similar to the significant damage found in the areas where the right collective lever arm had been attached before the helicopter impacted the ground. Examination of the two holes for the bolts that secured the two collector lever arms together found no indications of hole enlargement or longitudinal wear marks on the inside of bolt holes.

Various impact marks were identified that, according to Bell, were “consistent with an overtravel of the collective lever arm in the direction of an upward movement of the collective sleeve”and mast bumping. Mast bumping occurs on a two-bladed semi-rigid rotor when “when the system exceeds its teetering limit and strikes the mast of the helicopter with sufficient force to cause mast deformation and potentially mast failure”.

Bell…simulation of the Bell 214 helicopter’s response to a sudden and severe reduction of main rotor collective pitch (resulting from a failure of the collective flight control system) showed that the helicopter would respond with a severe right roll and a simultaneous nose-down pitch attitude. The math model simulation also showed that a sudden and severe reduction of main rotor collective pitch would cause the main rotor hub to exceed its flapping angle and the main rotor blade tips to deflect downward and possibly contact the tailboom due to the reduced amount of clearance.

The results of the math model simulation were closely aligned with the witness accounts from the flight crew of the helicopter behind the accident helicopter and the damage observed on the helicopter wreckage. For example, the nose-down pitch and right roll observed in the math model simulation was similar to the reported pitch and roll of the accident helicopter when the accident sequence began. Also, the main rotor mast showed damage consistent with mast bumping that resulted when the main rotor hub significantly exceeded its flapping angle.

Thus, the evidence showed that, when the accident helicopter’s main rotor hub exceeded its flapping angle, the resulting loss of clearance between the main rotor system blades and the tailboom caused the main rotor blades to contact the tailboom. This contact was severe enough to cause the aft tailboom section to completely separate from the rest of the tailboom, leading to a loss of pitch control.

NTSB comment that:

A review of maintenance records for the collective flight control system showed that the collective torque shaft support bracket had been replaced the day before the accident. The support bracket installation was found in the wreckage, and no evidence indicated that the installation of the replacement support bracket was faulty. The maintenance records showed that a functional check flight was completed after the support bracket replacement with no noted defects.

The non-routine work record stated collective system’s torque shaft support bracket was replaced due to wear beyond limits of the support bracket bearings; however, there was no information as to the circumstances that led to the discovery of the worn support bracket bearings. The parts control tag for the replacement support bracket stated the part was new; however, the parts control tag stated that it was installed on aircraft registration number N3897N instead of the accident helicopter.

The helicopter was equipped with a cockpit voice recorder (CVR), but that sustained substantial heat and impact damage and no data could be recovered.

NTSB Probable Cause

The overtravel of the collective sleeve, which led to a severe and sudden reduction in main rotor blade collective pitch, resulting in a loss of control of the helicopter.

The reason for the collective sleeve overtravel could not be determined since much of the collective control system was consumed in the post crash fire.

Organisational and Regulatory Background

NTSB explain that:

AAR Corp. acquired Presidential Airways, Inc. in April of 2010 from Xe Services, LLC. Xe Services, LLC. was formerly named EP Investments, LLC. EP Investments LLC. acquired Presidential Airways, Inc. in 2004.

A Previous Afghan Accident

In September 2004 the company lost a CASA 212 (radio call sign Blackwater 61) in Afghanistan. N960BW flew into a mountain. The two crew and the four passengers were killed, through one passenger survived for at least 8 hours, but died before help arrived. The NTSB reported that the probable cause was:

The captain’s inappropriate decision to fly a nonstandard route and his failure to maintain adequate terrain clearance, which resulted in the inflight collision with mountainous terrain.

Factors were the operator’s failure to require its flight crews to file and to fly a defined route of flight, the operator’s failure to ensure that the flight crews adhered to company policies and FAA and DoD Federal safety regulations, and the lack of in-country oversight by the FAA and the DoD of the operator.

Contributing to the death of one of the passengers was the operator’s lack of flight-locating procedures and its failure to adequately mitigate the limited communications capability at remote sites.

The NTSB also noted “numerous deficiencies in Presidential Airways’ Part 135 operations in Afghanistan” going on to comment:

By allowing such deficiencies to remain uncorrected, neither the FAA nor the DoD provided adequate oversight of Presidential Airways’ operations in Afghanistan. The Safety Board is concerned that the remoteness of such operations presents unique oversight challenges that have not been adequately addressed for civilian contractors that provide air transportation services to the U.S. military overseas.

NTSB made 6 recommendations.

Company History

Xe was an American private military company founded in 1997 by former US Navy SEAL officer Erik Prince as Blackwater, renamed as Xe Services in 2009 and known as Academi since 2011. AAR created its AAR Airlift Group on acquisition in 2010, which had:

…had about 900 employees at the time of the accident which included 179 flight crew members, 41 cabin crew members [crew chiefs], 15 flight attendants, and 259 mechanics. At the time of the accident, AAR Airlift operated the following aircraft: 2 Sikorsky S92 helicopters, 17 Sikorsky S61 helicopters, 3 Bell 214 helicopters, 8 Bombardier Dash 8 airplanes, 9 CASA 212 airplanes, 2 CASA 235 airplanes, and 3 Fairchild Swearingen SA227 Metroliner airplanes.

When Presidential Airways was sold, the management personnel were changed by AAR Airlift.

FAA Oversight

The change in head office location necessitated a change in FAA Flight Standards District Office (FSDO) overseeing the company. An FAA inspector commented:

When the Part 135 certificate was transferred to Orlando FSDO, there were 9 outstanding violations and a number of hot line complaints. The FAA Southern Region said all hot line complaints had to be answered and violations forwarded to the legal department

The violations included conducting Low Cost Low Altitude (LCLA) extractions, use of Russian TS1 fuel, operation Dash 8s from too narrow runways, and various maintenance irregularities. The hotline complaints allegedly…

…concerned personnel being forced to take flights into dangerous areas, complaints about Bell 214 parts, complaints about fuel [etc and] started shortly after the certificate was sold to AAR and key personnel were being replaced. The FAA Southern Region said all hot line complaints had to be answered and violations forwarded to the legal department.

So, as one FAA inspector commented:

The movement of the certificate from the Greensboro, NC (GSO) FSDO was a “long drawn out process”. The enforcement proceedings were “taken care of” before the name change and movement of the certificate. The certificate was officially moved in August, 2011.

Another said:

The Orlando FSDO was “in shock” over the size of the company operation. When the Part 135 operation had started it was in the Orlando FSDO and consisted of 2 airplanes [this was prior to the acquisition by Blackwater]. When the certificate was transferred back to the Orlando FSDO, the company was operating about 30 aircraft on the certificate.

At the time of the accident the FAA had yet to audit AAR’s deployed operations in Afghanistan.

An FAA inspector commented:

…Part 135 oversight was a “big” issue because you had to take everything on paper for what it was since we had no way of checking the operation in Afghanistan. What looked “great” on paper might not be representative of what was actually going on in the field. The FAA had no way of determining what was actually occurring in the field.

DOD Oversight

In contrast, DOD oversight…

…was conducted by an evaluator in Afghanistan who observed company operations, procedures, aircraft, and facilities. The evaluator was generally an operations specialist but was occasionally a maintenance specialist. DOD stated that it strived to conduct in-theater oversight twice a year (in 6-month intervals).

The NTSB’s review of the DOD’s operational reports and cockpit evaluations of the company from July 2010 to July 2011 (the company was known as Presidential Airways until January 1, 2011) showed satisfactory operations.

A DOD inspector commented:

The last biennial on site survey of AAR was moved up to an earlier time due to “risk factors” that appeared. These risk factors included the company moving its headquarters after being sold to AAR Airlift, a “huge” management change including several positions that were changed several times, the aircraft fleet increasing in number, and a shared concern with the FAA that the Quality Assurance program was not meeting standards. The company had been under increased surveillance due to these risk factors. The company was subsequently put back under “normal surveillance”.

However, crucially:

Between October 24 and 27, 2011, the DOD conducted a biennial survey of the company’s operations in Afghanistan. The NTSB’s review of the survey results indicated that all operational areas met the DOD quality and safety standards prescribed in Federal regulations.

On 6 September 2016 AAR’s Sikorsky S-61N, N805AR was destroyed during a post-maintenance check flight after experiencing a dual loss of engine power while in a hover near Palm Bay, Florida. There were three fatalities.

UPDATE 7 June 2019: FAA Enforcement Action

The U.S. Department of Transportation’s Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) proposes a $742,677 civil penalty against AAR Airlift Group…

The FAA alleges that between February 16, 2016 and January 27, 2017, AAR Airlift failed to properly document the replacement of components on 13 Sikorsky S-61N helicopters.

AAR Airlift allegedly documented in its maintenance records that it followed required maintenance procedures. However, the FAA alleges AAR did not at the time use or possess the special equipment necessary to properly replace the components. The components are hydraulic pistons [sic i.e. servos] that change the angle of the helicopters’ rotor blades….

The FAA further alleges that AAR Airlift operated the helicopters in violation of its operations specifications after it failed to use the required special equipment to replace the components. The flights occurred in Afghanistan, the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Niger and Uganda.

AAR Airlift has asked to meet with the FAA to discuss the case.

UPDATE 8 July 2021: AAR Corp. Settles False Claims Act Investigation by DOJ for $11 Million relating to “AAR’s maintenance of nine Sikorsky [LMT] S-61 helicopters used by U.S. Transportation Command (TRANSCOM) for moving troops and supplies in Afghanistan and U.S. African Command”.

AAR’s settlement with DOJ “resolves allegations that Airlift knowingly failed to maintain nine aircraft in accordance with contract requirements, and that because of this failure, the helicopters were not airworthy and should not have been certified by Airlift as ‘fully mission capable [FMC],’” DOJ said on July 7. Under some contracts, aircraft were to be FMC for at least 24 days a month with six days allotted for maintenance.

The DOJ investigation into AAR Corp. arose after a 2015 “qui tam” whistleblower lawsuit brought by Christopher Harvey, AAR Airlift’s former lead conformity specialist…

[The] Continuous Airworthiness Maintenance Program (CAMP) for S-61s “was incomplete and woefully out of date,” the lawsuit said. “For example, the S-61 manufacturer maintenance program requires a ‘debonding check’ to be conducted on the helicopter’s tail rotor blades every 12 months. This requires the maintenance crew to ensure that the blades on the tail rotor are not in danger of falling apart (a particular concern in sandy or salt-water environments).” Harvey’s team “discovered that there was no debonding check in the CAMP,” the lawsuit said. “When [Harvey] inquired about this he was shocked to learn that management of the maintenance department had no idea such a check was necessary, let alone whether it had been conducted. The problems with the S-61 CAMPs were only the tip of the iceberg. There were parts on the S-61s that could not be confirmed as valid for that aircraft. There were life-limited parts that were not being tracked such that there was no way to ensure that they would be inspected and replaced as required.”

As part of the agreement, AAR Corp. agreed to pay more than $429,000 to resolve faulty helicopter maintenance claims brought by the FAA in 2019.

Safety Resources

The European Safety Promotion Network Rotorcraft (ESPN-R) has a helicopter safety discussion group on LinkedIn. You may also find these Aerossurance articles of interest:

- Fatal S-61N Dual Power Loss During Post Maintenance Check Flight

- Critical Maintenance Tasks: EASA Part-M & -145 Change

- Misrigged Flying Controls: Fatal Maintenance Check Flight Accident

- Loose B-Nut: Accident During Helicopter Maintenance Check Flight

- Insecure Pitch Link Fatal R44 Accident

- UPDATE 1 February 2020: EC135 Main Rotor Actuator Tie-Bar Failure

- UPDATE 7 February 2020: S-61N Damaged During Take Off When Swashplate Seized Due to Corrosion

- UPDATE 9 May 2020: Ungreased Japanese AS332L Tail Rotor Fatally Failed

- UPDATE 5 September 2020: SAR AS365N3 Flying Control Disconnect: BFU Investigation

- UPDATE 7 August 2021: Prompt Emergency Landing Saves Powerline Survey Crew After MGB Pinion Failure

- UPDATE 8 January 2022: Fiery Fatal AW119 Accident in Russia After Loss of Tail Rotor Control

- UPDATE 17 September 2022: Canadian B212 Crash: A Defective Production Process

- UPDATE 10 December 2022: Main Rotor Blade Certification Anomaly in Fatal Canadian Accident

- UPDATE 24 December 2022: S-61N Accident in Afghanistan: Investigators Focus on Auxiliary Servocylinder

- UPDATE 29 July 2023: Missing Cotter Pin Causes Fatal S-61N Accident

Recent Comments