James Reason’s 12 Principles of Error Management

James Reason, Professor Emeritus, University of Manchester, set out 12 systemic human factors centric principles of error management in his book Managing Maintenance Error: A Practical Guide (co-written with Alan Hobbs and published in 2003).  These principles are valid beyond aviation maintenance and are well worth re-visiting:

These principles are valid beyond aviation maintenance and are well worth re-visiting:

- Human error is both universal & inevitable: Human error is not a moral issue. Human fallibility can be moderated but it can never be eliminated.

- Errors are not intrinsically bad: Success and failure spring from the same psychological roots. Without them we could neither learn nor acquire the skills that are essential to safe and efficient work.

- You cannot change the human condition, but you can change the conditions in which humans work: Situations vary enormously in their capacity for provoking unwanted actions. Identifying these error traps and recognising their characteristics are essential preliminaries to effective error management.

- The best people can make the worst mistakes: No one is immune! The best people often occupy the most responsible positions so that their errors can have the greatest impact…

- People cannot easily avoid those actions they did not intend to commit: Blaming people for their errors is emotionally satisfying but remedially useless. We should not, however, confuse blame with accountability. Everyone ought to be accountable for his or her errors [and] acknowledge the errors and strive to be mindful to avoid recurrence.

- Errors are consequences not causes: …errors have a history. Discovering an error is the beginning of a search for causes, not the end. Only be understanding the circumstances…can we hope to limit the chances of their recurrence.

- Many errors fall into recurrent patterns: Targeting those recurrent error types is the most effective way of deploying limited Error Management resources.

- Safety significant errors can occur at all levels of the system: Making errors is not the monopoly of those who get their hands dirty. …the higher up an organisation an individual is, the more dangerous are his or her errors. Error management techniques need to be applied across the whole system.

- Error management is about managing the manageable: Situations and even systems are manageable if we are mindful. Human nature – in the broadest sense – is not. Most of the enduring solutions…involve technical, procedural and organisational measures rather than purely psychological ones.

- Error management is about making good people excellent: Excellent performers routinely prepare themselves for potentially challenging activities by mentally rehearsing their responses to a variety of imagined situations. Improving the skills of error detection is at least as important as making people aware of how errors arise in the first place.

- There is no one best way: Different types of human factors problem occur at different levels of the organisation and require different management techniques. Different organisational cultures require different ‘mixing and matching’….of techniques. People are more likely to buy-in to home grown measures…

- Effective error management aims as continuous reform not local fixes: There is always a strong temptation to focus upon the last few errors …but trying to prevent individual errors is like swatting mosquitoes…the only way to solve the mosquito problem is drain the swamps in which they breed. Reform of the system as a whole must be a continuous process whose aim is to contain whole groups of errors rather than single blunders.

Error management has three components, says Reason:

- Reduction

- Containment

- Managing these so they remain effective

Its the third aspect that is most challenging according to Reason:

It is simply not possible to order in a package of Error Management measures, implement them and then expect them to work without further attention You cannot put them in place and then tick them off as another job completed. In an important sense, the process – the continuous striving toward system reform – is the product.

Further Reading on Safety (UPDATED)

The UK Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) has commented that:

Human Factors training alone is not considered sufficient to minimise maintenance error. Most of the [contributing factors] can be attributed to the safety culture and associated behaviours of the organisation.

Two other books by James Reason are also worth attention:

- Managing the Risks of Organizational Accidents

- The Human Contribution: Unsafe Acts, Accidents and Heroic Recoveries

Plus there is this presentation given to a Royal Aeronautical Society (RAeS) Human Factors Group conference in 2006 on Risk in Safety-Critical Industries: Human Factors Risk Culture Amy Edmonson discusses psychological safety and openness: VIDEO

This paper by the Health and Safety Laboratory is worth attention: High Reliability Organisations [HROs] and Mindful Leadership. Mindfulness is developed further in a paper by the Future Sky Safe EU research project and by Andrew Hopkins at the ANU. You may also be interested in these Aerossurance articles:

- How To Develop Your Organisation’s Safety Culture positive advice on the value of safety leadership and an aviation example of safety leadership development.

- How To Destroy Your Organisation’s Safety Culture a cautionary tale of how poor leadership and communications can undermine safety.

- The Power of Safety Leadership: Paul O’Neill, Safety and Alcoa an example of the value of strong safety leadership and a clear safety vision.

- Aircraft Maintenance: Going for Gold? looking at some lessons from championship athletes we should consider.

- Additionally this 2006 review of the book Resilience Engineering by Hollnagel, Woods and Leveson, presented to the RAeS: Resilience Engineering – A Review

- Plus this book review The Field Guide to Understanding Human Error by Dekker, also presented to the RAeS: The Field Guide to Understanding Human Error – A Review

A systems approach in healthcare: VIDEO

UPDATE 26 April 2016: Chernobyl: 30 Years On – Lessons in Safety Culture

UPDATE 1o June 2016: This article is cited in Zero to HRO (High Reliability Organising): Abandoning Antediluvian Accident Theory

UPDATE 1 August 2016: We also recommend this article: Leicester’s lesson in leadership, published in The Psychologist.

UPDATE 10 August 2016: We also like this article by Suzette Woodward after she delivered the James Reason Lecture. She highlights:

- The first thing you can do [when investigating] is learn to listen

- Listen to what people are saying without judgement

- Listen to those that work there every day to find out what their lives are like

- Listen to help you piece the bits of the jigsaw together so that they start to resemble a picture of sorts

- The second thing you can do is resist the pressure to find a simple explanation

- The third thing you can do: don’t be judgemental

She goes on:

- Find the facts and evidence early

- Without the need to find blame

- Strengthen investigative capacity locally

- Support people with national leadership

- Provide a resource of skills and expertise

- Act as a catalyst to promote a just and open culture

UPDATE 28 August 2016: We look at an EU research project that recently investigated the concepts of organisational safety intelligence (the safety information available) and executive safety wisdom (in using that to make safety decisions) by interviewing 16 senior industry executives: Safety Intelligence & Safety Wisdom. They defined these as:

Safety Intelligence the various sources of quantitative information an organisation may use to identify and assess various threats.

Safety Wisdom the judgement and decision-making of those in senior positions who must decide what to do to remain safe, and how they also use quantitative and qualitative information to support those decisions.

The topic of weak or ambiguous signals was discussed in this 2006 article: Facing Ambiguous Threats

UPDATE 8 February 2018: The UK Rail Safety and Standards Board (RSSB) say: Future safety requires new approaches to people development They say that in the future rail system “there will be more complexity with more interlinked systems working together”:

…the role of many of our staff will change dramatically. The railway system of the future will require different skills from our workforce. There are likely to be fewer roles that require repetitive procedure following and more that require dynamic decision making, collaborating, working with data or providing a personalised service to customers. A seminal white paper on safety in air traffic control acknowledges the increasing difficulty of managing safety with rule compliance as the system complexity grows: ‘The consequences are that predictability is limited during both design and operation, and that it is impossible precisely to prescribe or even describe how work should be done.’ Since human performance cannot be completely prescribed, some degree of variability, flexibility or adaptivity is required for these future systems to work.

They recommend:

- Invest in manager skills to build a trusting relationship at all levels.

- Explore ‘work as done’ with an open mind.

- Shift focus of development activities onto ‘how to make things go right’ not just ‘how to avoid things going wrong’.

- Harness the power of ‘experts’ to help develop newly competent people within the context of normal work.

- Recognise that workers may know more about what it takes for the system to work safety and efficiently than your trainers, and managers.

UPDATE 12 February 2018: Safety blunders expose lab staff to potentially lethal diseases in UK. Tim Trevan, a former UN weapons inspector who now runs Chrome Biosafety and Biosecurity Consulting in Maryland, said safety breaches are often wrongly explained away as human error.

Blaming it on human error doesn’t help you learn, it doesn’t help you improve. You have to look deeper and ask: ‘what are the environmental or cultural issues that are driving these things?’ There is nearly always something obvious that can be done to improve safety.

One way to address issues in the lab is you don’t wait for things to go wrong in a major way: you look at the near-misses. You actively scan your work on a daily or weekly basis for things that didn’t turn out as expected. If you do that, you get a better understanding of how things can go wrong.

Another approach is to ask people who are doing the work what is the most dangerous or difficult thing they do. Or what keeps them up at night. These are always good pointers to where, on a proactive basis, you should be addressing things that could go wrong.

UPDATE 13 February 2018: Considering human factors and developing systems-thinking behaviours to ensure patient safety

Medication errors are too frequently assigned as blame towards a single person. By considering these errors as a system-level failure, healthcare providers can take significant steps towards improving patient safety.

‘Systems thinking’ is a way of better understanding complex workplace issues; exploring relationships between system elements to inform efforts to improve; and realising that ‘cause and effect’ are not necessarily closely related in space or time.

This approach does not come naturally and is neither well-defined nor routinely practised…. When under stress, the human psyche often reduces complex reality to linear cause-and-effect chains.

Harm and safety are the results of complex systems, not single acts.

UPDATE 2 March 2018: An excellent initiative to create more Human Centred Design by use of a Human Hazard Analysis is described in Designing out human error

HeliOffshore, the global safety-focused organisation for the offshore helicopter industry, is exploring a fresh approach to reducing safety risk from aircraft maintenance. Recent trials with Airbus Helicopters and HeliOne show that this new direction has promise. The approach is based on an analysis of the aircraft design to identify where ‘error proofing’ features or other mitigations are most needed to support the maintenance engineer during critical maintenance tasks.

The trial identified the opportunity for some process improvements, and discussions facilitated by HeliOffshore are planned for early 2018.

UPDATE 11 April 2018: The Two Traits of the Best Problem-Solving Teams (emphasis added):

…groups that performed well treated mistakes with curiosity and shared responsibility for the outcomes. As a result people could express themselves, their thoughts and ideas without fear of social retribution. The environment they created through their interaction was one of psychological safety.

Without behaviors that create and maintain a level of psychological safety in a group, people do not fully contribute — and when they don’t, the power of cognitive diversity is left unrealized. Furthermore, anxiety rises and defensive behavior prevails.

We choose our behavior. We need to be more curious, inquiring, experimental and nurturing. We need to stop being hierarchical, directive, controlling, and conforming.

We believe this applies to all teams not just those solving problems. Retrospective management application of culpability decisions aids have no more a place when trying to solve problems than they do in other work activities.

UPDATE 22 December 2019: Our article is also cited here Anatomy of errors: My patient story and Supporting Patient Safety Through Education and Training.

UPDATE 24 July 2022: What Lies Beneath: The Scope of Safety Investigations

Aerossurance’s Andy Evans was recently interviewed about safety investigations, the perils of WYLFIWYF (What-You-Look-For-Is-What-You-Find) and some other ‘stuff’ by with Sam Lee of Integra Aerospace:

UPDATE 24 October 2022: The Royal Aeronautical Society (RAeS) has launched the Development of a Strategy to Enhance Human-Centred Design for Maintenance. Aerossurance‘s Andy Evans is pleased to have had the chance to participate in this initiative.

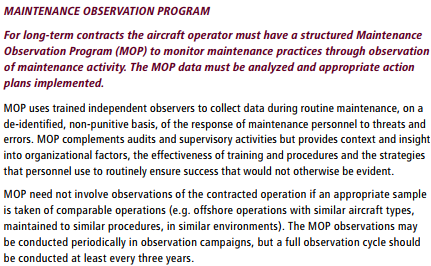

Maintenance Observation Program

Aerossurance worked with the Flight Safety Foundation (FSF) to create a Maintenance Observation Program (MOP) requirement for their contractible BARSOHO offshore helicopter Safety Performance Requirements to help learning about routine maintenance and then to initiate safety improvements:

Aerossurance can provide practice guidance and specialist support to successfully implement a MOP.

Aerossurance is an Aberdeen based aviation consultancy. For advice you can trust on practical and effective safety management, contact us at: enquiries@aerossurance.com

Recent Comments