Undetected Cross Connection Maintenance Error Resulted in Diamond DA42NG N591ER’s Hard Landing During a Maintenance Check Flight

On 25 May 2022, Diamond DA42NG N591ER departed London International Airport, Ontario, on a maintenance check flight but suffered control difficulties and was forced to make a hard landing on the grass alongside the runway. The Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) issued their safety investigation report on 5 January 2024. We examine the maintenance human factors involved.

The Accident Flight

The maintenance check flight followed a 2000-hour inspection (“including a mechanical and structural inspection, and general refurbishing”) that had been completed at the Diamond Aircraft Industries facilities at London International Airport.

During the take-off, when the aircraft became airborne, the aircraft yawed abruptly to the left. The pilot attempted to correct for the unexpected yaw but had difficulty maintaining directional control of the aircraft.

The pilot attempted to make an emergency landing on Runway 27; however, during the approach, the pilot continued to have difficulty controlling the aircraft and instead attempted to land on Taxiway A before ultimately landing on the grass between the runway and the taxiway.

Diamond DA42NG N591ER Maintenance Error: Satellite image of London Airport, Ontario, showing the runways and taxiway involved in this occurrence, as well as the aircraft’s approximate final resting spot (Credit: Google Earth, with TSB annotations)

When the aircraft touched down hard on the grass, the rudder and the left-wing aileron mass balance weight broke off. The landing gear collapsed, and the aircraft slid to a stop approximately 265 feet from the initial impact point.

The aircraft was substantially damaged but the pilot was uninjured.

The Safety Investigation & Our Comments

Upon initial examination it was discovered that the rudder moved in the opposite direction to the pilot input. Significantly, during the preceding maintenance the rudder guide tubes had been replaced.

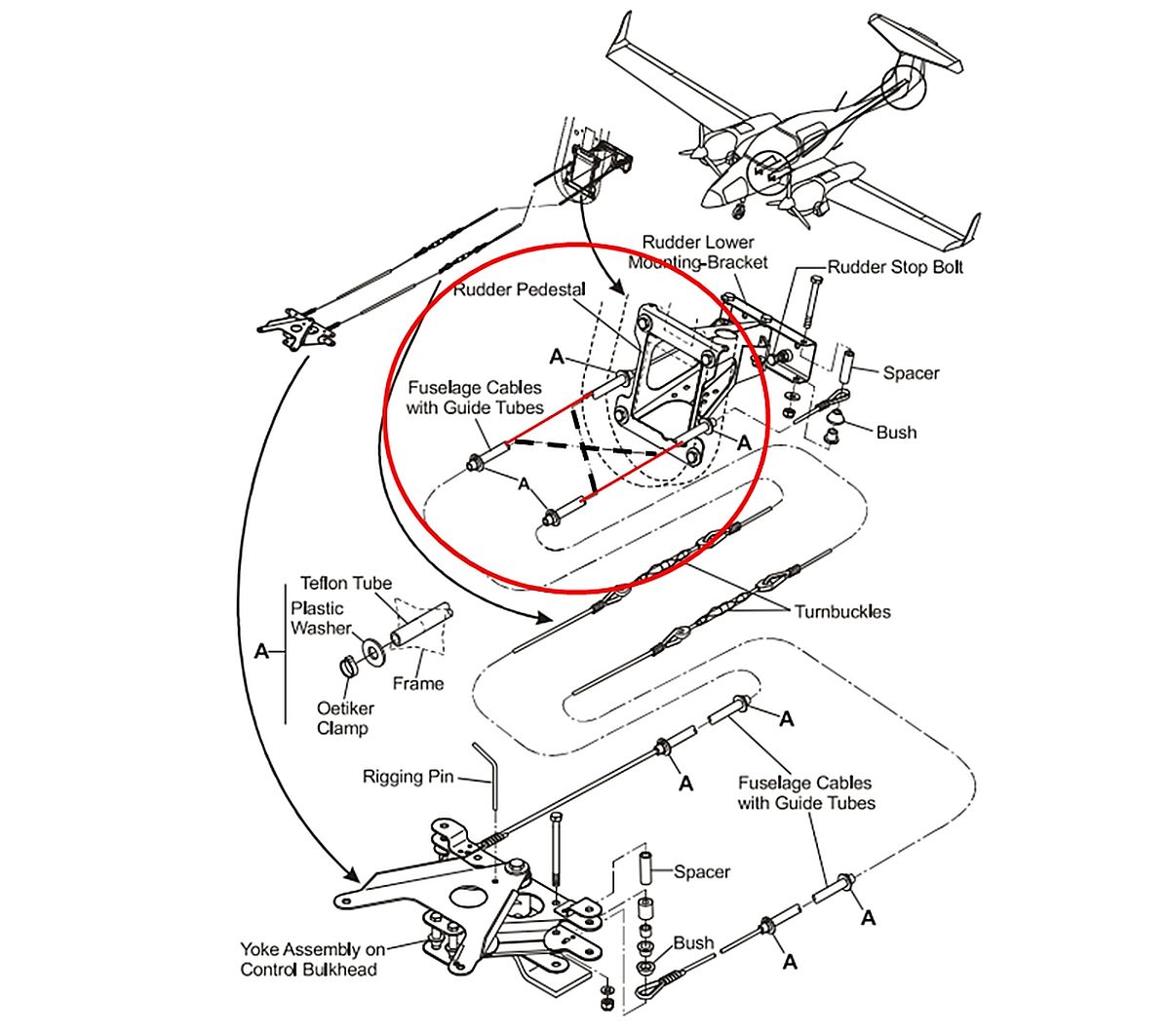

[The Aircraft] Maintenance Manual (AMM) explains that the “two fuselage cables go through Teflon tubes in the rear fuselage. The cables attach to the rudder lower mounting bracket. The cables cross over each other in the rear fuselage”

Diamond DA42NG N591ER Maintenance Error: Rudder controls in the fuselage, with location of crossing guide tubes circled. The solid red lines in the circle indicate the actual installation (cables not crossed), while the dashed lines indicate the proper installation (cables crossing over). (Credit: Diamond Aircraft Industries GmbH, DA 42 NG Airplane Maintenance Manual, Revision 5 [22 December 2021], Section 27-20: Flight Controls – Rudder, p. 9, with TSB annotations)

The rudder cable guide tubes are not normally replaced…during the course of regular maintenance because they are rarely found to be defective, and there is no specific requirement to change or inspect them at regular intervals.

The AMM also provides some troubleshooting guidance, which suggests that rudder stiffness or catching may be caused by the rudder cables chaffing in the guide tubes. The AMM suggests to replace the rudder cables and guide tubes; however, there is no method or procedure in the AMM specific to replacing the guide tubes.

The AMM system description does explain and illustrate that the cables cross over, but that is not referenced from AMM section for the task. The AMM contains instructions for the replacement of a single cable but makes no mention that it crosses from one side to the other (i.e. assumes the other cable is in place).

TSB note that the only other information was in production drawings. These apparently could be requested, but wasn’t requested for this task. Clearly a maintenance organisation owned by the Type Certificate (TC) Holder has an advantage accessing production data, though if it is needed its a sign of an inadequacy in the AMM.

Investigators determined the tube were therefore installed…

…without the aid of specific procedures, guidance, or supervision.

We discuss the supervision aspect further below. As noted above, the lack of procedures and guidance was not a ‘Failure to Follow (F2F) procedures’ by maintenance personnel (a popular ’cause’ for unskilled ‘investigators’ who are driven by completing culpability checklists & flow charts) but in fact a failure of the TC Holder to provide specific instructions for the completion of this rare task.

As a result, the rudder cable guide tubes were installed incorrectly, running parallel to each other instead of crossing over at the rear of the fuselage as prescribed in the AMM.

When the rudder cables were threaded through the rudder cable guide tubes, they also ran in parallel when connected to the rudder lower mounting bracket in the rear of the aircraft. As a result, the rudder moved in the direction opposite to the pilot’s input.

In relation to supervision, TSB note that the task came about because an:

…apprentice pointed out to the weekend shift team lead, an ACA [aircraft certification authority] holder [i.e. authorised certifying staff], that the rudder cable guide tubes were damaged and was then verbally authorized to replace them.

Crucially

…neither the team lead nor the apprentice entered the guide tube discrepancy on the work order discrepancy sheet as required…

The apprentice proceeded to remove both of the aft fuselage rudder cables, then removed the guide tubes, which can be accomplished without being able to see how they are routed through the rear fuselage. New guide tube material was obtained and the guide tubes were installed and secured.

Not surprisingly, as this task is rarely necessary, this was….

…the first time the apprentice changed the rudder cable guide tubes on a DA42 and he was not aware that they had to cross over each other.

Significantly:

The apprentice’s previous experience with rudder controls at Diamond Aircraft Industries was on a DA20 aircraft. The rudder cables on that aircraft run parallel to each other.

This shows how prior experience can build false expectations.

The team lead who supervised the apprentice’s work on the rudder cable guide tube installation had previous experience changing the rudder cable guide tubes and cables on DA42 aircraft and was aware that the rudder cable guide tubes crossed over.

The team lead did not provide the apprentice with any reference material, such as the manufacturer’s installation drawings. The team lead also did not ensure that the apprentice knew and understood that the rudder cable guide tubes crossed over each other in the rear fuselage, as described in the AMM.

TSB do not discuss the team lead’s past training in supervisory tasks (if any).

The cables were then fitted on a subsequent shift by different personnel. As no task paperwork had been created for the change of tubes, those personnel were not alerted to the potential for a latent error to have been introduced.

A functional check was attempted but failed to detect the problem. TSB note that…

…it is very difficult to see the rudder surface from the cockpit, and the rudder pedals from the tail area…

This was further complicated by he task being conducted by one person, hence the functional check….

…did not identify that the rudder was rigged in reverse.

Although not stated in the AMM or required by regulations, it should be noted that it is beneficial to have two people perform the check: one in the cockpit actioning the command throughout the full range of movement, and the other monitoring the surface to confirm the proper direction and full range of movement. It is important that the communication between the two people performing the check be clear, and both need to agree that the surface is moving in the direction commanded.

Again this appears not to be a F2F procedures by the personnel involved but an absence of effective procedures to follow:

The investigation also determined that if procedures requiring the inspection of flight controls do not provide specific instructions regarding how to ensure the rudder surface is moving in the correct direction, flight controls that have been rigged in reverse may not be recognized.

Our pedantic separation of ‘failures’ by frontline maintenance personnel from pre-existing systemic organisational ‘failures’ is because these are different issues, involving different organisations, with different solutions. Its too easy at the maintenance organisation level to only consider corrective actions directed at individual front line personnel. This is especially common when an organisation’s procedures dictate the completion of culpability checklists & flow charts for an event review panel, or similar, with the specific aim of determining culpability (or ‘accountability’). Such investigations suffer from the WYLFIWYF (What-You-Look-For-Is-What-You-Find) phenomena and are equally venerable is classification aids (such as MEDA or HFACS) are inappropriately used to guide the gathering of evidence rather than to guide analysis.

Oddly these culpability/accountability processes, normally proprietary products lacking any scientific examination of their effectiveness and adopted after buying third-party training, are generally structurally inhibited from considering if the organisation’s Accountable Manager (the Accountable Executive in Canada) is actually ‘accountable’!

During the course of the overhaul, the occurrence pilot, who held an FAA inspection authorization, conducted an annual inspection of the aircraft as required by the FAA. The inspection included checking the “[f]light and engine controls—for improper installation and improper operation.” No discrepancies were identified by the pilot when the flight controls were inspected.

This will have contributed to confidence that all was well.

According to the work order, the replacement of the rudder cables was signed off as completed on 16 February 2022; however, the replacement was actually accomplished from 9 to 11 January 2022. The replacement of the rudder cables was conducted, and then later stamped as completed, by the team lead of the weekday shift, who held an SCA [shop certification authority].

The independent inspection was stamped as completed by an ACA holder.

Disappointingly, the maintenance organisation…

….could not provide [TSB with] records of the practical examination for either of the aircraft certification authority (ACA) or shop certification authority (SCA) holders involved in the rudder cable replacement, the independent inspection, and the maintenance release of the aircraft.

Oversight by the regulator, Transport Canada, is not discussed by TSB.

Ultimately:

The investigation was unable to determine if all steps listed in the AMM, particularly the inspection of the controls that had been adjusted and a test for the correct range of movement, had been completed, given that the rudder cables did not cross in the rear fuselage.

As part of the pilot’s pre-flight inspection, pilots are to “check free and correct movement up to full deflection” and the before take-off checklist includes an item to check the “unrestricted free movement, correct sense”. As well as the difficult seeing the rudder from the cockpit noted above…

…this item is difficult to accomplish with weight on wheels given the connection to the nose wheel steering.

Thus two more lines of defence had limited effectiveness.

TSB Findings on Causal and Contributing Factors

- The apprentice who installed the rudder cable guide tubes did so without the aid of specific procedures, guidance, or supervision. As a result, the rudder cable guide tubes were installed incorrectly, running parallel to each other instead of crossing over at the rear of the fuselage as prescribed in the Airplane Maintenance Manual.

- When the rudder cables were threaded through the rudder cable guide tubes, they also ran in parallel when connected to the rudder lower mounting bracket in the rear of the aircraft. As a result, the rudder moved in the opposite direction of pilot input.

- The replacement of the rudder cable guide tubes was not recorded, likely because the overall maintenance task was incomplete at the end of the work shift. As a result, the personnel who later certified the work and conducted the independent inspection were not aware of the guide tube replacement and did not check to ensure it had been completed correctly.

- During certification of the maintenance work performed, the mis-rigged rudder was not detected due to the assumption that the rudder cables were properly installed, the rudder having a proper range of movement, and that likely only one person performed the test for correct range of motion during the dual inspections.

- It is very difficult to see the rudder surface from the cockpit, and the rudder pedals from the tail area. As a result, the flight control portions of the annual and pre-flight inspections, which were accomplished by a single individual, did not identify that the rudder was rigged in reverse.

- After take-off, the aircraft yawed in the opposite direction expected by the pilot. In an attempt to regain directional control of the aircraft, the pilot increased rudder input to the right; however, the aircraft continued to yaw and bank to the left. Consequently, the pilot conducted an emergency landing, which resulted in substantial damage to the aircraft.

Our Further Safety Observations

This investigation highlights the potential for a DA42 cross-connection error that is difficult to identify without a functional checks with at least two people. The best solution is to eliminate the potential through design. Aerossurance has discussed Human Centred Design in presentations in 2017 to EASA and the RAeS: Helicopter Flying Control Maintenance HF Accidents

Surprisingly no safety recommendations are made by TSB despite identifying systemic issues within the maintenance organisation and with the DA42’s maintenance data issued by the TC Holder. While some investigation reports do proliferate low value recommendations, a total absence of recommendations is not an example of proactive leadership by a safety investigation body. Unsurprisingly in the absence of any safety recommendations, disappointingly:

The Board is not aware of any safety action taken following this occurrence.

One might suspect that every inaction by an investigator can result in an equally and opposite inaction after the investigation. However, a diligent maintenance organisation and TC Holder would have acted on their own initiative.

A public inquiry chaired by Anthony Hidden QC investigated the maintenance related 1988 Clapham Junction rail accident. In the report, known as the Hidden Report, he commented:

There is almost no human action or decision that cannot be made to look flawed and less sensible in the misleading light of hindsight.

It is essential that the critic should keep himself constantly aware of that fact.

This point equally applies to critics on social media who are quick to point blame at individuals or complacently claim it wouldn’t happen to them.

Its disappointing how few illustrations TSB have included in this report.

Safety Resources

The Royal Aeronautical Society (RAeS) has launched the Development of a Strategy to Enhance Human-Centred Design for Maintenance. Aerossurance‘s Andy Evans is pleased to have had the chance to participate in this initiative.

You may also find these Aerossurance articles of interest:

- How To Develop Your Organisation’s Safety Culture

- James Reason’s 12 Principles of Error Management

- Psychology of Blame

- Airworthiness Matters: Next Generation Maintenance Human Factors

- Aircraft Maintenance: Going for Gold?

- B1900D Emergency Landing: Maintenance Standards & Practices

- Meeting Your Waterloo: Competence Assessment and Remembering the Lessons of Past Accidents

- What Lies Beneath: The Scope of Safety Investigations

Aerossurance’s Andy Evans was interviewed about safety investigations, the perils of WYLFIWYF (What-You-Look-For-Is-What-You-Find) and some other ‘stuff’ by with Sam Lee of Integra Aerospace:

Recent Comments