AAIB Report on Glasgow Police Scotland Airbus EC135T2+ Helicopter Clutha Accident (Bond [now Babcock] G-SPAO)

The UK Air Accidents Investigation Branch (AAIB) has published their report (which has since been subject to minor corrections) into the fatal accident involving a Airbus Helicopters (formerly Eurocopter) EC135T2+ G-SPAO. It crashed onto the Clutha Vaults Bar in Glasgow, Scotland on the night of Saturday 29 November 2013. The helicopter was operated under a UK CAA issued Police Air Operator’s Certificate by Bond Air Services for Police Scotland. In addition to the pilot and two police observers, seven people in the packed bar died.

The Flight

The AAIB report:

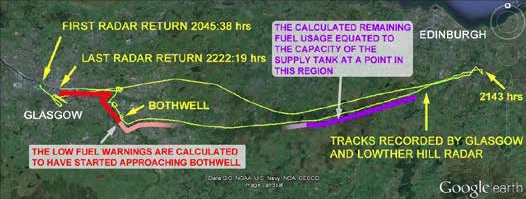

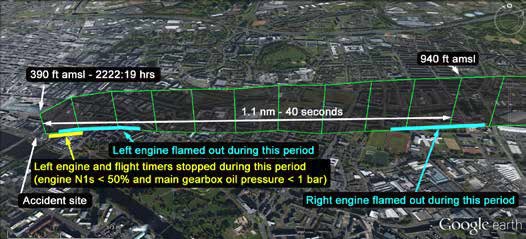

The helicopter departed Glasgow City Heliport (GCH [then located at Stobcross Quay alongside the River Clyde]) at 2044 hrs on 29 November 2013, in support of Police Scotland operations. On board were the pilot and two Police Observers. After their initial task, south of Glasgow City Centre [at Oatlands, 2 nm from GCH], they completed four more tasks; one in Dalkeith, Midlothian [south of Edinburgh], and three others to the east of Glasgow, before routing back towards the heliport. When the helicopter was about 2.7 nm from GCH, the right engine flamed out [at around 22:21:40].

They note that the single engine emergency shutdown checklist was not completed.

Shortly [~32s] afterwards, the left engine also flamed out. An autorotation, flare recovery and landing were not achieved and the helicopter descended at a high rate onto the roof of the Clutha Vaults Bar, which collapsed. The three occupants in the helicopter and seven people in the bar were fatally injured. Eleven others in the bar were seriously injured.

Organisational Matters, Police Observers & Operational Tasking

Police Scotland is the UK’s second largest police service. It was formed in 1 April 2013, from the merger of 8 regional forces and several specialist agencies, but has not been without controversy and the Chief Constable has recently resigned. Originally the Glasgow based helicopter had been a Strathclyde Police asset, Strathclyde being the region of Scotland around Glasgow.

The helicopter is tasked by the Police Scotland control room with, typically short-notice, ‘non-routine’ tasks. An inventory of ‘routine’ tasks is contained in a folder available to the crew. The AAIB report that:

The primary duties of the front seat observer [FSO] are the operation of the FLIR Television/IR camera, to assist the pilot and rear seat observer [RSO] with navigation, using visual references and maps, and to assist the pilot as and when directed.

The primary duties of the rear seat observer are the navigation to and from each task, utilising police role equipment and navigational aids, and Police radio communications.

The front seat observer normally assumes ‘operational command’ of the tasking of the aircraft. However, when two experienced observers fly together, the more experienced observer will normally assume operational command in relation to the tasking of the helicopter.

Given that both observers were experienced it is likely that they would alternate operational command. However, it is not known who had operational command on the accident flight.

In addition to their other training, police observers undergo recurrent Crew Resource Management (CRM) training. The specific CRM training is not identified but BAS do market such training. While part of the crew, as they have specific in-flight tasks, the UK CAA treat police observers as passengers. Police tactical communication is by the emergency services Airwave secure radio, which is recorded.

The pilot and both Observers had their own set of radio controls… It is usual for the pilot to monitor and transmit on the two available ATC channels, while the Observers operate up to three Airwave channels. In order to enhance their situational awareness, pilots may also monitor the Airwave channels and Observers may monitor both ATC channels.

The first task, close to their base, was a non-routine search. After completing that search after 37 minutes at 21:21, the FSO informed control they were going to conduct a routine task at Dalkeith, 20 minutes flying time away. After 3 minutes on-site on an task, the pilot informed ATC at 21:50 they were heading west towards Bothwell, near Glasgow, for another routine task, the first of three routine tasks conducted. AAIB identify that no tactical radio communication was occurring and due to the lack of a cockpit voice recorder (see below) were unable to identify what discussion was being conducted within the aircraft.

Fuel Policy

At the time of the accident, the operator’s Operations Manual stated that the IFR Final Reserve Fuel was to be 85kg (equivalent to 30 mins at endurance speed). It was also stated that:

If it appears to the aircraft Commander that the Final Reserve Fuel may be required, a PAN call should be made. If the Final Reserve fuel is then subsequently reached, this should be upgraded to a MAYDAY.

The Fuel System and Fuel Status

No pre-impact technical defect was identified in any part of the aircraft or its systems. The AAIB explain:

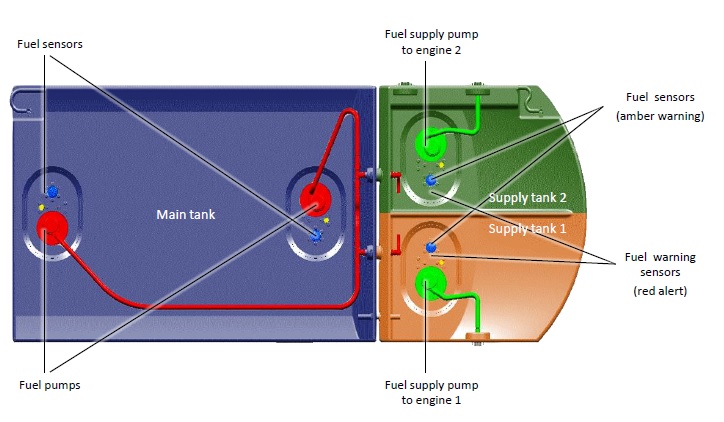

Fuel in the helicopter’s main fuel tank is pumped by two transfer pumps into a supply tank, which is divided into two cells. Each cell of the supply tank feeds its respective engine. During subsequent examination of the helicopter, 76 kg of fuel was recovered from the main fuel tank. However, the supply tank was found to have been empty at the time of impact. It was deduced from wreckage examination and testing that both fuel transfer pumps in the main tank had been selected off for a sustained period before the accident, leaving the fuel in the main tank, unusable. The low fuel 1 and low fuel 2 warning captions [before 22:06], and their associated audio attention-getters, had been triggered and acknowledged, after which, the flight had continued beyond the 10-minute period specified in the Pilot’s Checklist Emergency and Malfunction Procedures.

[Based on a study of fuel consumption] It was concluded that the transfer of fuel from the main tank to the supply tank stopped while the helicopter was returning to Glasgow from Dalkeith, leaving only the fuel in the supply tank available to the engines… The supply tank capacity is affected by the pitch attitude of the helicopter because fuel can spill from the supply tank back into the main tank, via the connecting overflow channels. Also, the pitch attitude of a helicopter is dynamic, constantly varying, whereas the modelling of the pitch attitude during the flight was based on low sample rate radar data which relied on a assumptions, with associated margins for error.

The LOW FUEL warnings were calculated to have been activated as the helicopter approached Bothwell, east of Glasgow.

During the investigation, the EC135’s fuel sensing, gauging and indication system, and the Caution Advisory Display and Warning Unit were thoroughly examined. This included tests resulting from an incident involving another EC135 T2+.

Despite extensive analysis of the limited evidence available, it was not possible to determine why both fuel transfer pumps in the main tank remained off during the latter part of the flight, why the helicopter did not land within the time specified following activation of the low fuel warnings and why a MAYDAY call was not received from the pilot. Also, it was not possible to establish why a more successful autorotation and landing was not achieved, albeit in particularly demanding circumstances.

The lack of a cockpit voice recorder meant the AAIB were not able to determine if any distractions had occurred inside the aircraft at a critical moment. Extensive trials were conducted to simulate the fuel system behaviour during the flight under AAIB supervision. Aerossurance was able to view the articulated Airbus Helicopters EC135 fuel system test rig at Donauwörth during a visit arranged by the International Society of Air Safety Investigators (ISASI) in August 2015 as part of their 2015 Annual Conference.

Perspex panels (visible in the right hand image above) were added to allow visibility of fuel behaviour as the aircraft mock-up was tilted to replicate the aircraft’s manoeuvring. These tests were supplemented by flight tests to support the investigation. The EC135, as an aircraft type, had achieved 3 million flying hours without any previous fuel starvation occurrences reported.

Final Moments

AAIB noted at the single engine emergency shutdown checklist items (a memory drill) was not completed after the first engine flamed out. Irrespective of that flameout the AAIB also note that in accordance with the operator’s fuel policy:

Since the helicopter had 76 kg of fuel on board at the time of the accident, the pilot might have been expected to make a PAN call, upgrading it to a MAYDAY on reaching the Final Reserve Fuel IFR

After the second engine flamed out about 32s later at around 22:22:13 (+/- 5s) and at an altitude of between 700ft and 500ft, just 3nm from the helicopter’s base, the ROTOR RPM warning caption illuminated and its aural tone sounded. This indicated that the main rotor speed had decreased below 97%.

This warning then extinguished, re‑illuminated and extinguished again. It finally re-illuminated and stayed on for the remainder of the flight, as the helicopter descended.

About 8 seconds after the second engine flamed out, the aircraft impacted the roof of the bar, a single story building at a high decent rate, nose up with no rotor speed evident and little forward speed (indicating a flare had been performed, though the height at which it had could not be determined). The flat roof collapsed. The AAIB assessed the impact deceleration to be 70g and non-survivable for the crew.

A Radar Altimeter (RADALT) is not a certification requirement but is required by certain operating rules, including by UK CAA for police operations. The AAIB note that it is powered from the Avionic-Shed Bus 1 busbar which is automatically disconnected in the event of the loss of power from both electrical generators, although it can be switched to the Essential Bus by one switch selection. As this was not done at this point of high pilot workload, no RADALT data was presented in the final moments.

AAIB Conclusions

The AAIB state in their analysis that:

In summary, the investigation could not establish why a pilot with over 5,500 hours flying experience in military and civil helicopters, who had been a Qualified Helicopter Instructor and an Instrument Rating Examiner, with previous assessments as an above average pilot, did not complete the actions detailed in the Pilot’s Checklist Emergency and Malfunction Procedures for the LOW FUEL 1 and LOW FUEL 2 warnings.

That is further discussed in a BBC TV interview with Chief Inspector of Air Accidents Keith Conradi here. The AAIB identified the following causal factors:

- 73 kg of usable fuel in the main tank became unusable as a result of the fuel transfer pumps being switched off for unknown reasons.

- It was calculated that the helicopter did not land within the 10-minute period specified in the Pilot’s Checklist Emergency and Malfunction Procedures, following continuous activation of the low fuel warnings, for unknown reasons.

- Both engines flamed out sequentially while the helicopter was airborne, as a result of fuel starvation, due to depletion of the supply tank contents.

- A successful autorotation and landing was not achieved, for unknown reasons.

The AAIB identified the following contributory factors:

- Incorrect management of the fuel system allows useable fuel to remain in the main tank while the contents in the supply tank become depleted.

- The RADALT and steerable landing light were unpowered after the second engine flamed out, leading to a loss of height information and reduced visual cues.

- Both engines flamed out when the helicopter was flying over a built-up area.

Safety Recommendations

Seven Safety Recommendations have been made, all directed at regulators, two relating to radar altimeter emergency power and five to recording devices:

Safety Recommendation 2015-030: It is recommended that, when the European Aviation Safety Agency requires a radio altimeter to be fitted to a helicopter operating under an Air Operator’s Certificate, it also stipulates that the equipment is capable of being powered in all phases of flight, including emergency situations, without intervention by the crew.

Safety Recommendation 2015-031: It is recommended that, when the Civil Aviation Authority require a radio altimeter to be fitted to a helicopter operating under a Police Air Operator’s Certificate, it also stipulates that the equipment is capable of being powered in all phases of flight, including emergency situations, without intervention by the crew.

Safety Recommendation 2015-032: It is recommended that the Civil Aviation Authority requires all helicopters operating under a Police Air Operators Certificate, and first issued with an individual Certificate of Airworthiness before 1 January 2018, to be equipped with a recording capability that captures data, audio and images in crash‑survivable memory. They should, as far as reasonably practicable, record at least the parameters specified in The Air Navigation Order, Schedule 4, Scale SS(1) or SS(3) as appropriate. They should be capable of recording at least the last two hours of (a) communications by the crew, including Police Observers carried in support of the helicopter’s operation, and (b) images of the cockpit environment. The image recordings should have sufficient coverage, quality and frame rate characteristics to include actions by the crew, control selections and instrument displays that are not captured by the data recorder. The audio and image recorders should be capable of operating for at least 10 minutes after the loss of the normal electrical supply.

Safety Recommendation 2015-033: It is recommended that the Civil Aviation Authority requires all helicopters operating under a Police Air Operators Certificate, and first issued with an individual Certificate of Airworthiness on or after 1 January 2018, to be fitted with flight recorders that record data, audio and images in crash-survivable memory. These should record at least the parameters specified in The Air Navigation Order, Schedule 4, Scale SS(1) or SS(3), as appropriate. They should be capable of recording at least the last two hours of (a) communications by the crew, including Police Observers carried in support of the helicopter’s operation, and (b) cockpit image recordings. The image recordings should have sufficient coverage, quality and frame rate characteristics to include control selections and instrument displays that are not captured by the other data recorders. The audio and image recorders should be capable of operating for at least 10 minutes after the loss of the normal electrical supply.

Safety Recommendation 2015-034: It is recommended that the Civil Aviation Authority considers applying the requirements of AAIB Safety Recommendation 2015 – 032 and AAIB Safety Recommendation 2015 – 033 to State aircraft not already covered by these Safety Recommendations.

Safety Recommendation 2015-035: It is recommended that the European Aviation Safety Agency mandate the ICAO Annex 6 flight recorder requirements for all helicopter emergency medical service operations, regardless of aircraft weight. The last two hours of flight crew communications and cockpit area audio should be recorded. The cockpit area audio recording should continue for 10 minutes after the loss of normal electrical power.

Safety Recommendation 2015-036: It is recommended that the European Aviation Safety Agency mandate image flight recorder requirements for all helicopter emergency medical service operations, regardless of aircraft weight. The image recordings should have sufficient coverage, quality and frame rate characteristics to include actions by the crew, control selections and instrument displays that are not captured by a data recorder. The recording should be of the last two hours of operation, including at least 10 minutes after the loss of normal electrical power to the flight recorder.

UPDATE 21 July 2016: The AAIB have issued an update of responses to the recommendations.

UPDATE 18 June 2018: EASA published further responses in their Annual Safety Recommendations Review 2017.

Data Recorders

This Police Scotland chartered aircraft was not fitted with either a Cockpit Voice Recorder (CVR) or Flight Data Recorder (FDR), nor was it required to be by either regulation or by the Police Scotland contract. The absence of onboard recorders complicated an already challenging accident investigation (as it had in AAIB investigations into 8 other police aviation accidents since 1985), hence 5 of the 7 recommendations are focused on recorders. The AAIB do report that:

…data and recordings were recovered from non-volatile memory (NVM) in systems on board the helicopter, and radar, radio, police equipment and CCTV recordings were also examined.

Ironically, Police Scotland is involved in a court case to gain access to the Cockpit Voice and Flight Data Recorder (CVFDR) from a fatal August 2013 G-WNSB AS332L2 Super Puma offshore helicopter accident at Sumburgh. We have discussed the initial case: Scottish Court Orders Release of Sumburgh Helicopter CVFDR. An appeal by pilots union BALPA is awaited in December 2015.

Aerossurance has reported that EASA Launch Rule Making Team on In-flight Recording for Light Aircraft. While the scope of the RMT.0271/.0272 project includes helicopters <3,175 kg used for commercial air transport (including used for Helicopter Emergency Medical Services), this would not apply to Police aircraft as they are State aircraft subject to national, not EASA, rule making. Aerossurance has also discussed mini-recorders, the value of routine flight data monitoring and cockpit video: That Others May Live – Inadvertent IMC & The Value of Flight Data Monitoring.

In March 2014 Airbus Helicopters announced that the Appareo Vision 1000 equipment used in that case will be standard on their new production helicopters. Vision 1000 proved critical in the investigation of a loss of control accident to an Alaskan State Trooper AS350B helicopter in 2013. NTSB made a number of findings and recommendations and again they emphasised the value of recorders as the cause of the Alaskan accident could have be so easily misidentified. Vision 1000 was first introduced in 2009.

The AAIB highlight that they made recommendations to the UK CAA in 2000 for fitment of lightweight recorders after an accident to medical helicopter AS355F1, G-MASK. The CAA accepted that recommendation but reported that no suitable recorders were available. CAA stated then:

If and when suitable lightweight and low cost flight recorders become available, the CAA will reassess the flight recorder requirements.

They also mention two other accidents:

-

G-CSPJ 18 July 2003 Hughes 269HS (500C) AAIB Report: The AAIB made two recorder recommendations to the Department for Transport (DfT) to support international rulemaking. The CAA simply noted these recommendations were not directed to them. The AAIB subsequently reported that in a letter to the AAIB dated 14 October 2004, the DfT gave its full support to these recommendations.

-

G-BXLI 22 January 2005 Bell 206B III AAIB Report: The AAIB made two recommendations to EASA to promote research and adoption of light-weight recorders. This is one of the accidents that influenced EASA RMT.0271/.0272 and prior EASA research.

We hope this summary of the AAIB Report is helpful. The full report can be found here for further study.

Legal / Political Matters & Reactions

The AAIB investigation is intended to help prevent future accident. not to assign blame or liability. Under Scottish Law the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service (COPFS), headed by the Lord Advocate, is responsible for:

- Investigating the circumstances of a death

- Instructing investigations to try to find out the cause of a death

- Considering whether there should be any criminal proceedings arising out of the circumstances

- Reporting the case to Crown Counsel for a decision as to whether there should be criminal prosecution and/or a Fatal Accident Inquiry.

COPFS has previously stated they “must have the final report from the AAIB before it can complete its investigation”. They state Police Scotland, the charterer of the helicopter:

…are carrying out enquiries such as interviewing witnesses and obtaining specialist reports and opinions and will submit a report to the Procurator Fiscal who has overall responsibility for the investigation of the death.

After the AAIB report was released COPFS are quoted as saying:

The Crown will now conduct further investigations into some of the complex issues raised by the AAIB report. We will endeavour to do this as quickly as possible but these matters are challenging and the necessary expertise is restricted to a small number of specialists. We will continue to keep the families advised of progress with the investigation. As this tragedy involves deaths in the course of employment a Fatal Accident Inquiry [FAI] is mandatory. This will be held as soon as is possible. An FAI will allow a full public airing of all the evidence at which families and other interested parties will be represented. It is right that the evidence can be vigorously tested in a public setting and be the subject of judicial determination.

It is interesting to note that an FAI, the Scottish equivalent on a coroner’s inquest, is described as mandatory because the pilot and observers died while at work, as there has in the past been exceptions (such as the loss of the Clyde tug, Flying Phantom, although in that case there were prosecutions under Health and Safety legislation). In the case of the last helicopter FAI, following the April 2009 loss of G-REDL, the AAIB report was published in November 2011, but a further 26 months elapsed before the FAI commenced in Aberdeen. The employers, Police Scotland and BAS, have issued statements. The Scottish Government has also issued a statement. The BBC have reported other reactions.

UPDATE 25 October 2015: The Scottish Cabinet Secretary for Justice Michael Matheson MSP has urged the UK government to follow the Clutha crash report recommendations on flight recorders in helicopters as soon as possible. Cabinet Secretary for Infrastructure, Investment and Cities Keith Brown has said:

We are also investigating whether or not there are actions that we could take ourselves to help this process. We are now keen to hold an early meeting with UK counterparts to discuss in detail the implications of the report and timetable for acting on the recommendations.

It is not clear if this will mean Scottish Government action to ensure early fitment of recorders on the Police Scotland helicopter (a tender was issued in May 2015 by the Scottish Police Authority for contracting of a Police Helicopter from October 2016 onwards without a requirement CVR or FDR) and the two new Scottish Ambulance Service HEMS EC145T2 helicopters (also chartered from BAS).

UPDATE 27 October 2015: A good bit of safety focused journalism by Helen McArdle of the Glasgow Herald has got confirmation that Police Scotland do intend to fit recorders ‘going forward’. The results of the tender mentioned above are reportedly due to be announced tomorrow. The accident was also discussed in the Scottish Parliament, with Michael Matheson stating in response to a question on the early fitment of recorders:

…we are looking at every avenue that is open to us and at what further measures need to be taken in relation to those who operate in Scottish contracts to ensure that the recommendations that have been set by the AAIB are implemented swiftly.

UPDATE 4 December 2015: UK CAA have issued FACTOR F6/2015 with their response on Recommendations 2015-031 to -034.

UPDATE 28 November 2016: Three years after the accident the families still await the Crown Office to organise a Fatal Accident Inquiry (FAI).

A spokesman for the Crown Office said: “The AAIB report into the Clutha tragedy, published last year, raised a number of issues which require further investigation by Police Scotland under the direction of the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service. “This is a challenging and highly complex inquiry. While we understand that the process may be frustrating for those affected by the tragedy, it is essential that the investigation must be thorough and effective to meet close scrutiny in judicial proceedings.

UPDATE 22 December 2016: The UK CAA issue safety directive SD-2016/006: State Helicopter Flight Recorder Requirements applicable to operators conducting State emergency services Public Transport (PT) helicopter operations in the UK and requiring either an FDR or cockpit image recorder.

UPDATE 24 November 2017: The Crown Counsel, the most senior lawyer in Crown Office, has formally instructed a FAI be held in 2018. In a press release the COPFS said:

Crown Counsel have instructed that the appropriate form of proceedings at this stage is an inquiry into the deaths of all who lost their lives in terms of the Inquiries into Fatal Accidents and Sudden Deaths etc. (Scotland) Act 2016.

Following submission of a detailed report by the [COPFS] Helicopter Team, Crown Counsel have also concluded that there is insufficient evidence available to justify instructing criminal proceedings.

Although the evidence currently available would not justify criminal proceedings, the Crown reserves the right to raise criminal proceedings should evidence in support of that course of action become available to prosecutors.

COPFS appreciate that the wait for a decision regarding proceedings must have been extremely difficult and stressful for those affected and we will keep them informed of significant developments.

UPDATE 4 August: 2018: US HEMS EC135 Dual Engine Failure: 7 July 2018

UPDATE 10 August 2018: Clutha helicopter disaster FAI to begin 8 April 2019. The formal order is published on the Clutha FAI web page.

The Fatal Accident Inquiry

UPDATE 8 April: 2019: The FAI begins today in a temporary court at Hampden Park, Glasgow under Sheriff Principal Craig Turnbull. The FAI is inquisitorial not adversarial and it was not designed to apportion blame. It will hear evidence over 3 months of sittings between now and August 2019:

- The inquiry will sit between 8 and 10 April 2019 and then adjourn until Wednesday 17 April 2019.

- The inquiry will sit on 17 and 18 April 2019, then adjourn until Tuesday 23 April 2019.

- The inquiry will sit between 23 April and 3 May 2019, then adjourn until Tuesday 7 May 2019.

- The inquiry will will sit between 7 and 17 May 2019, then adjourn until Monday 1 July 2019.

- As matters presently stand, the inquiry will then sit continuously throughout July and August 2019 (with the exception of Monday 15 July 2019 which is a local holiday in Glasgow).

The list of issues to be considered include:

- how fuel was managed on the aircraft and in particular why both transfer pumps were switched OFF, rendering unusable the otherwise usable fuel in the main tank

- whether the Pilot’s Checklist was available to the pilot

- whether it was within the competence of a helicopter pilot qualified to fly G-SPAO on police duties to comply with the requirements of the Pilot’s Checklist

- at what stage in flight did the LOW FUEL warnings likely occur

- why, having acknowledged the LOW FUEL warnings, did the pilot not complete the actions detailed in the Pilot’s Checklist

- whether the timing and/or the initially intermittent character of the LOW FUEL warnings contributed to the Pilot’s Checklist procedure not being completed

- whether there have been other instances of LOW FUEL warnings not being followed

- whether the pilot believed the fuel transfer pumps were operating, notwithstanding the LOW FUEL warnings, because he believed he had switched the fuel transfer pumps back ON, and if so whether the design or layout of the switches contributed to such errors occurring

- whether the pilot believed the transfer pumps were operating, notwithstanding the LOW FUEL warnings, as a result of erroneous fuel indications being displayed on the CAD

- what the root cause or causes were of any such erroneous fuel indications and whether they were adequately investigated and acted upon prior to the accident

- whether there was a failure of any part of the CAD prior to the accident

- what steps were open to a helicopter pilot qualified to fly this helicopter after both engines flamed out

- whether the designed time-interval between engine flame-outs was compromised by the design of the fuel tank system and, in particular, the undivided volume above the supply tanks, which, depending on the attitude of the helicopter, might have allowed fuel to migrate from one supply tank to another

- why autorotation, flare recovery and landing were not completed successfully

- whether the ability to carry out autorotation, flare recovery and landing was compromised by the design of the cockpit layout.

Potential precautions that could have prevented the accident to be discussed include:

- including within the fuel contents indication system a caution or warning that both transfer pumps were switched OFF

- including within the fuel contents indication system a caution or warning that a fuel pump, having been switched OFF, has since been submerged in fuel

- designing the fuel tank system and fuel contents indication system in such a way that the fuel transfer pumps did not require to be switched ON or OFF during flight

- including within the fuel contents indication system a caution or warning, in the case of anomalous or implausible combinations of outputs from the sensors

- designing the fuel tank system, and in particular the differential capacities of the supply tanks, in such a way as to ensure that the design objective of creating an interval of 3-4 minutes between engine flame-outs, or such other interval of time as would be represented by 4.5kg of fuel, or any other safe interval of time, was achieved

- ensuring that power to the RADALT and steerable landing light was automatically maintained in the event of a double engine flameout.

Possible contributory defects to be considered include whether:

- any aspect of the system of maintenance of G-SPAO, including its washing regime, contributed to the contamination of the fuel and/or the fuel tank system with water

- any aspect of the pre-flight check procedures contributed to the accident occurring

- any aspect of the training of pilots, in particular, with regard to fueling, pre-flight checks, the pilot handover procedure, the operation of the fuel contents indication system, erroneous fuel indications, the appropriate response to fuel cautions and warnings, and the execution of an autorotation at night, contributed

- the practice of the “day-shift” pilot handing the aircraft over already fueled to the “night-shift” pilot contributed.

The FAI will also review progress with recommendations from the AAIB report.

It is reported that:

A total of 57 Crown witnesses are expected to give evidence at the inquiry, down from a previous estimate of 85. Police have taken more than 2,000 statements as part of preparations for the FAI, while the Crown has around 1,400 productions.

On day 1 eyewitnesses gave evidence.

UPDATE 10 April 2019: The AAIB gave evidence on the 9th and 10th of April. The causes of death were also confirmed. Scottish Review summary (note these are legal summaries and therefore not fully accurate on reporting aviation details).

UPDATE 17 April 2019: After a break AAIB evidence continued, with a focus on FDR data and the fuel system engineering. Scottish Review weekly summary.

UPDATE 18 April 2019: Evidence continued from an AAIB on the fuel system and the testing of the fuel recovered.

UPDATE 23 April 2019: Evidence heard from a duty Air Traffic Controller at Glasgow, the Accountable Manager of the Police AOC and other Police Observers. One observer told the FAI he was in a police helicopter with the Clutha crash pilot previously when a red fuel warning light came on.

UPDATE 24 April 2019: Scottish Review weekly summary.

UPDATE 25 April 2019: Two days of focus on the fuel system design with the Airbus Helicopters Compliance Verification Engineer (CVE).

UPDATE 26 April 2019: The FAI continued with further discussion on fuel probe reliability and moisture in fuel as well as evidence from an Airbus test pilot.

UPDATE 30 April 2019: The evolution of the Eurocopter/Airbus fuel system and fuel displays was discussed today at the FAI. Scottish Review weekly summary.

UPDATE 1 May 2019: The inquiry hears of concerns raised about maintenance workload and a fuel sensor malfunction that was only recorded in a shift diary post-it note. A fuel quality specialist also gave evidence.

UPDATE 2 May 2019: More engineering evidence, the refueller is questioned and a further police witness is called.

UPDATE 7 May 2019: The FAI heard evidence of an Operator’s Proficiency Check (OPC) the pilot had completed in which “all emergencies were completed to a very high standard“. Monitoring of landings with less than 90 kg of fuel is now in place.

UPDATE 8 May 2019: Scottish Review weekly summary.

UPDATE 9 May 2019: Much discussion over two days of complaints from 2003 of water ingress into the fuel system after compressor washes and a modification issued in April 2014. The FAI had previously heard that no evidence of water contamination in the fuel tanks after the crash.

UPDATE 11 May 2019: The FAI is told of earlier fuel indication inaccuracies.

UPDATE 13 May 2019: Tech Logs entries in the months before the accident showed “repeated concerns about fuel readings” the inquiry heard.

UPDATE 22 May 2019: Scottish Review summary. The FAI…

…may finish earlier than expected, if the Crown and other legal parties can reach agreements about certain evidence. The FAI has taken a planned six-week break from Monday, because the facilities at Hampden stadium are required for several events including this weekend’s Scottish Cup final, two men’s and women’s football international matches, and a concert by the American performer Pink. Hampden was chosen as the inquiry venue because its facilities could cope with the numbers of people attending – in some days approaching 50, plus the public and press.

The inquiry is due to hear evidence from pilots and engineers during the first two weeks of July. However, Sheriff Principal Craig Turnbull indicated that he may be ready to receive summations from the various parties by mid-July.

UPDATE 1 July 2019: After scheduled break the FAI resumed with the pilot who flew the aircraft on its penultimate flight, describing that and commenting he had never seen a fuel warning while flying the type.

UPDATE 2 July 2019: The pilot’s past OPCs were briefed to the Inquiry.

UPDATE 3 July 2019: Previous fuel indication anomalies are briefed.

UPDATE 9 July 2019: Several years earlier another police helicopter in the UK had suffered fuel indication anomalies, but that had eventually been resolved.

UPDATE 16 July 2019: A pilot who had flown G-SPAO on a routine flight to Aberdeen on the day of the accident explained to the FAI “how an issue with the number one supply tank became apparent and the helicopter had to be shut down then restarted.”

UPDATE 17 July 2019: There is disagreement about one aspect of the validity of data from post-accident test flights.

UPDATE 18 July 2019: The last day on evidence focused on a behavioural analysis. Representations from the parties are expected on 5 August 2019.

UPDATE 5 August 2019: The public hearings come to an end. The Sheriff’s findings will follow in due course. There is still no sign of the long awaited CAA Onshore Helicopter Safety Review.

UPDATE 7 August 2019: The Scottish Review writes:

The sheriff has now started his own deliberations on the cause of the crash and any lessons to be learned. He gave the Crown Office four weeks to lodge an explanation for the lengthy delay to the start of the inquiry, which was promised several times since the tragic events of 29 November 2013.

Let us now have a review of the fatal accident inquiry system writes Tom Marshall, who represented families at the G-REDL FAI in The Herald.

UPDATE 21 August 2019: The Scottish Review summary.

UPDATE 30 October 2019: The Sheriff Principal’s FAI determination is issued.

Previous UK Police Aircraft Accidents

The AAIB mention eight previous investigations involving UK police aircraft (none of these fitted with flight recorders. For convenience there are links below:

- G-BSWR 13 July 2011 Britten-Norman BN2T Islander (fixed wing) AAIB Report

-

G-SAEW 21 April 2000 AS355F2 AAIB Report

-

G-EMAU 9 October 1998 AS355N AAIB Report

-

G-EYEI 24 January 1990 Bell 206B II AAIB Report (Note: Clyde Helicopters operated for Strathclyde Police)

- G-KATY 15 May 1985 Edgley EA7 Optica (fixed wing) AAIB Report

Other Helicopter Safety Resources

In 2014 Aerossurance wrote about a Japanese Police AgustaWestland A109K2 accident: Fatal Police Helicopter Double Engine Flameout Over City Centre.

Aerossurance has also previously written of a fatal AgustaWestland A109E charter helicopter accident in London, that like the Glasgow accident, resulted in a third party casualty on the ground. We have also recently discussed an AW139 night take-off accident which further highlighted safety in the business sector. The investigation was aided by the availability of CVR and FDR data: Fatal Night-time UK AW139 Accident Highlights Business Aviation Safety Lessons

UPDATE 23 April 2016: Dim, Negative Transfer Double Flameout. This article examined a double engine flameout and associated human factors in an older generation helicopter in New Zealand. Fortuitously this day-time HEMS incident did not result in any casualties.

UPDATE 24 October 2019: EC135P2+ Loss of NR Control During N2 Adjustment Flight

UPDATE 24 November 2019: Austrian Police EC135P2+ Impacted Glassy Lake

UPDATE 21 December 2019: BK117B2 Air Ambulance Flameout: Fuel Transfer Pumps OFF, Caution Lights Invisible in NVG Modified Cockpit

UPDATE 2 January 2020: EC130B4 Destroyed After Ice Ingestion – Engine Intake Left Uncovered

UPDATE 18 July 2020: Vortex Ring State: Virginia State Police Bell 407 Fatal Accident

UPDATE 31 January 2021: Fatal US Helicopter Air Ambulance Accident: One Engine was Failing but Serviceable Engine Shutdown

UPDATE 20 November 2021: NVIS Autorotation Training Hard Landing: Changed Albedo

Aerossurance is pleased to sponsor the Chartered Institute of Ergonomics & Human Factors’ (CIEHF) Human Factors in Aviation Safety Conference that takes place at the Radison Blu Hotel, East Midlands Airport, 9-10 November 2015.

.jpg)

Recent Comments