Merlin Night Airprox: Systemic Issues

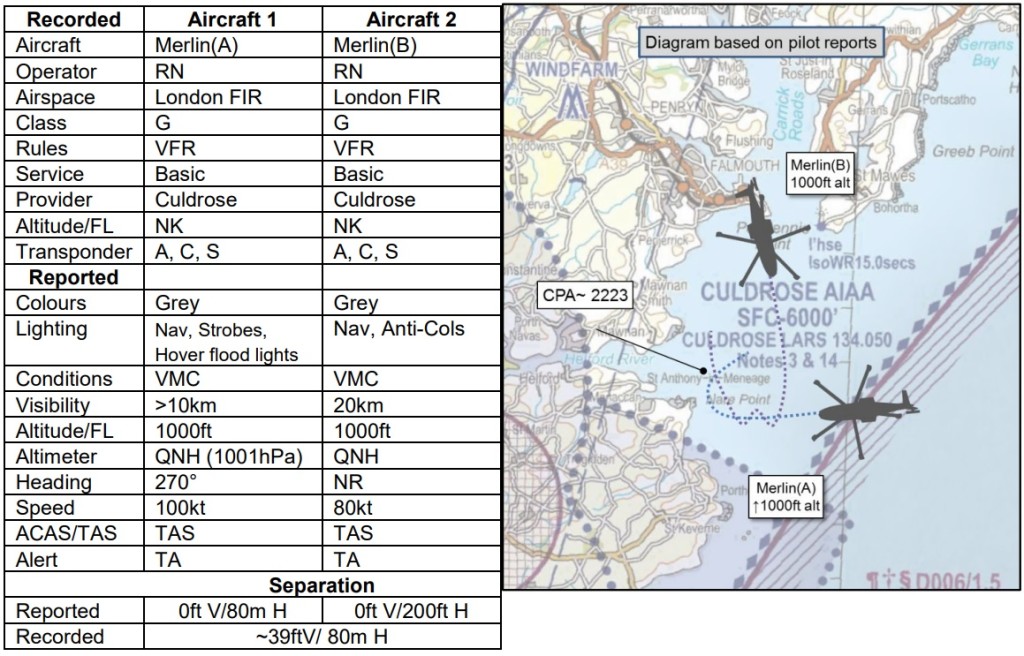

A Royal Navy Leonardo Merlin helicopter from RNAS Culdrose was in the hover, at night on 7 August 2018, slightly to the west of Falmouth at 40ft, facing west, with all floodlights on. The crew were conducting SAR training with a ‘dead-Fred’ training aid. According to a report from the UK Airprox Board:

At around 2217hrs, the final lift was being conducted and, as the training aid was being brought to the door, the ‘double-lift man’ and winch operator lost control of it and it fell back into the water.

At this time, they heard another Merlin call that it was inbound on the Falmouth one-way route, that they were visual with [their] Merlin and would be passing over and crossing in front of the aircraft en-route to the Helford river. This was acknowledged…

A short while later, the training aid had been recovered and the crew prepared to [return to base]. The Observer at the mission booth was tasked with contacting ATC for a clearance on the one-way route. At the same time, the LHS pilot conducted post-hoist-operation challenge and response checks, and the RHS pilot transitioned away from the hover, climbing to 1300ft QNH (approximately 1000ft QFE).

As the aircraft levelled off, the [Traffic Advisory System] TAS declared ‘traffic 10 o’clock, 0 miles’. On looking in the 10 o’clock an aircraft was seen level at approximately 4nm but converging. At this point the aircraft commander liaised with the Observer and it was made clear that they did not have clearance on the Falmouth oneway route. A right-hand turn was initiated and, after turning through 30°, [the other] Merlin was seen at the same height crossing right-to-left about 4 rotor spans away (80m). The handling pilot instigated an avoiding action turn to the right, rolling out facing east, and an Airprox was declared to ATC. They continued out to sea until a clearance for the one-way route was obtained.

This was categorised as a Cat A aiprox (“serious risk of collision“) with separation of just 39ft V / 80m H.  The UKAB note that:

The UKAB note that:

The Merlin pilots shared an equal responsibility for collision avoidance and not to operate in such proximity to other aircraft as to create a collision hazard . If the incident geometry is considered as converging then Merlin(A) pilot [the one that had been hovering] was required to give way to Merlin(B).

A safety investigation was conducted:

Although both crews had received TAS warnings, the pilots assumed the TAS had ‘self-detected’ which had been a common fault when the TAS was first installed, but was no longer a fleet wide issue.

Despite a well integrated glass coskpit…

..the TAS display unit was located on the lateral consoles in the cockpit (under the window, by the pilot’s elbow) making it difficult to view, and therefore the crews were reliant on the aural warning, which could easily be lost in the busy cockpit environment.

This suggests TAS was a bolt on after thought.

The [investigation reported that] crews [were] provided with detailed information on how the TAS works, but not what to do once it had alerted. Furthermore, there was no policy within the Merlin fleet about how to respond to a TAS alert, and the crews did not double-press the TI selector for an aural update which would have given them updates on the TA.

Additionally:

Merlin(A) had limited fuel remaining and, because of an earlier delay for weapon loading training, had launched with 200 kgs less fuel than originally expected. This, combined with the dropping of the dead-Fred dummy back into the water, meant that the aircrew were conducting 20min fuel checks which continuously predicted only 6 mins fuel allowance to minimum landing fuel which added to the crew’s workload. Furthermore, a number of crew in both aircraft were undergoing night-currency checks prior to deployment the following week.

On the two aircraft a total of 7 crew members were undergoing checks.

The OSI highlighted that pressure to complete the checks to ensure currency, plus an increased workload, led to a lack of CRM in both aircraft during periods of the flights. Furthermore, because of the checks during night flying, some crew members exceeded their crew duty period. Over the previous months, the Sqn had been suffering from a sustained period of minimal preparation and recovery time between tasking, which had previously been highlighted to the HQ. Consequently operational tempo had resulted in a lack of manpower and aircraft because maintainers were becoming fatigued and this was putting the Sqn under pressure to deliver the suitably qualified aircrew. Furthermore, supervision was stretched due to the Sqn being under pressure to prepare for the forthcoming deployment.

There is no indication in the report on what the deployment was but on 18 August 2018 the Royal Navy’s newest aircraft carrier, HMS Queen Elizabeth, departed Portsmouth, bound for the USA to land fast jets on deck for the very first time during WESTLANT 18. It was also reported that:

[Due to an] unserviceable digital display in the rear of the aircraft, the pilot had the settings on his digital map display set to those normally adopted by the aircrewman; this was an unfamiliar setting for the pilot which led him to slow down on recovery to regain his situational awareness. Subsequently, his turn to position for the recovery on the one-way route took longer than would normally be expected, which may have been why Merlin(A) had assumed he had already passed. …the crews were not operating with NVGs and that an additional tool used by the maritime fleet for situational awareness, an i-band transponder, was not working on Merlin(A), again contributing to a loss of situational awareness for Merlin(B). …a radar head had once been positioned such that it provided coverage of the Falmouth Bay area which, had it still existed, would have allowed the controller to see where the two Merlins were…had been decommissioned.

Analysis

The UKAB described this Airprox as “a classic example of how a number of factors all lined up in the classic ‘Swiss cheese’ model“:

- the crews had been under pressure to complete their tasks prior to deployment;

- Merlin(A) was short of fuel;

- Merlin(A) was further delayed on recovery by having to re-retrieve the dummy;

- Merlin(A) pilot had given an inaccurate position estimate;

- Merlin(B) was slower during recovery than normal;

- ATC had no radar coverage of Falmouth Bay;

- the recovery deconfliction plan was not robust;

- the Merlin crews were not aware that their TAS had been updated to prevent self-alerting;

- the TAS display was in a poor location within the cockpit;

- Merlin(A)’s i-band transponder was unserviceable;

- Merlin(B)’s pilot was using an unfamiliar display setup; and

- Merlin(A)’s pilot likely lost situational awareness on Merlin(B) due to task focus or misperception of Merlin(B)’s actual position.

The UKAB opine:

Ultimately, much of this was a result of the crews trying to do too much in one sortie…

They also make the unnecessarily speculative statement:

…the Board wondered what role Sqn supervision had taken in the oversight of the night’s activities.

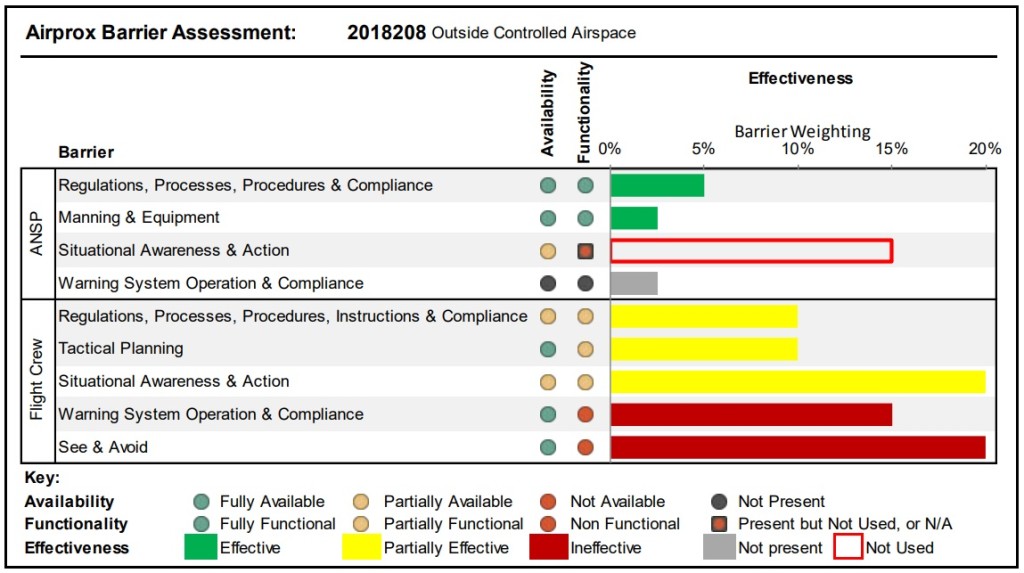

Assessing the effectiveness of the safety barriers::

- Regulations, Processes, Procedures, Instructions and Compliance were assessed as partially effective because there was a lack of robust TAS procedures for the Merlin.

- Tactical Planning was assessed as partially effective because there had been an opportunity to deconflict the aircraft in Falmouth Bay at the planning stage of the sortie.

- Situational Awareness and Action were assessed as partially effective, although the pilots had generic situational awareness from the RT, they did not fully act upon it.

- Warning System Operation and Compliance were assessed as ineffective because the TAS display was not able to be seen easily by the pilots, and the audible alerts were not acted upon.

- See and Avoid were assessed as ineffective because neither pilot saw the other aircraft in time to take timely and effective avoiding action.

Other MAC Safety Resources

Aerossurance has previously published:

- Military Mid Air Collisions

- Military Airprox in Sweden

- North Sea S-92A Helicopter Airprox Feb 2017

- Mid Air Collision Typhoon & Learjet 35

- USMC CH-53E Readiness Crisis and Mid Air Collision Catastrophe

- Avoiding Mid Air Collisions: 5 Seconds to Impact

- AAIB Highlight Electronic Conspicuity and the Limitations of See and Avoid after Mid Air Collision

- Fatal Biplane/Helicopter Mid Air Collision in Spain, 30 December 2017

- A319 / Cougar Airprox at MRS: ATC Busy, Failed Transponder and Helicopter Filtered From Radar

- UPDATE 12 May 2019: Alaskan Mid Air Collision at Non-Tower Controlled Airfield

- UPDATE 14 August 2021: Alpine MAC ANSV Report: Ascending AS350B3 and Descending Jodel D.140E Collided Over Glacier

See also:

- UPDATE 20 May 2019: US Army C-27/USAF C-130 Night MAC 1 December 2014: The Investigation attributed the collision to a lack of visual scan by both crews, over reliance on TCAS and complacency despite the inherent risk associated with night, low-level, VFR operations using Night Vision Goggles.

Recent Comments