Metro III Low-energy Rejected Landing and CFIT

The Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) has issued a report on a fatal accident to Fairchild SA227-AC Metro III, C-GFWX, operated by Perimeter Aviation at Sanikiluaq, Nunavut, on the coast of Hudson Bay on 22 December 2012. The route from Winnipeg is normally operated by sister company Keewatin Air, but Perimeter were chartered to help catch-up a backlog due to poor weather. According to the TSB:

Following an attempted visual approach to Runway 09, a non-precision non-directional beacon (NDB) Runway 27 approach was conducted. Visual contact with the runway environment was made and a circling for Runway 09 initiated. Visual contact with the Runway 09 environment was lost and a return to the Sanikiluaq NDB was executed.

The ground track flown from the initial arrival from the west up to final impact (Credit: TSB)

A second NDB Runway 27 approach was conducted with the intent to land on Runway 27. Visual contact with the runway environment was made after passing the missed approach point. Following a steep descent, a rejected landing was initiated at 20 to 50 feet above the runway.

The final, tailwind, approach had been unstable.

The vertical profile of the final approach (Credit: TSB)

The TSB determined:

…that the aircraft came in too high, too steep, and too fast, striking the ground 525 feet past the end of the runway after an unsuccessful attempt to reject the landing.

The actual descent profile versus an optimal Continuous Descent Final Approach (CDFA) approach (Credit: TSB)

The 2 crew and 6 adult passengers, secured by their seatbelts, suffered injuries ranging from minor to serious. A lap-held infant, not restrained by any device or seatbelt, was fatally injured.

At a news conference on release of the report, investigators said inclement weather, poor visibility, fatigue and a departure from established protocols all played a part in the accident. As the company did not normally fly this route there had been problems obtaining approach plates and survival kits (which were to be borrowed from their sister company). These problems and a defective cargo door indication delayed departure. The TSB commented:

The captain felt frustrated as a result of the pre-flight preparation issues, and it is evident from analysis of his speech that signs of frustration persisted after takeoff. The captain’s use of 43 expletives in conversation with the first officer (FO) during the non emergency, non stressful, 2-hour period preceding the occurrence, showed a rate of approximately 21.5 swear words per hour. This type of behaviour was seen as being out of character for the captain.

They added that circadian rhythm, the long day and a 1.5 hours wake period in his previous nights sleep mean…

…acute sleep disruption may have played a role in the captain’s behaviour during the flight by increasing the risk for fatigue and its associated performance decrements.

Two recommendations were issued in relation to the carriage of infants. The airline issued a statement on their actions after the accident.

TSB Causes and Contributory Factors

- The lack of required flight documents, such as instrument approach charts [NOTE: they had been inadvertently forgotten], compromised thoroughness and placed pressure on the captain to find a work-around solution during flight planning. It also negatively affected the crew’s situational awareness during the approaches at CYSK (Sanikiluaq).

- Weather conditions below published landing minima for the approach at the alternate airport CYGW (Kuujjuarapik) and insufficient fuel to make CYGL (La Grande Rivière) eliminated any favourable diversion options. The possibility of a successful landing at CYGW was considered unlikely and put pressure on the crew to land at CYSK (Sanikiluaq).

- Frustration, fatigue, and an increase in workload and stress during the instrument approaches resulted in crew attentional narrowing and a shift away from well-learned, highly practised procedures.

- Due to the lack of an instrument approach for the into-wind runway and the unsuccessful attempts at circling, the crew chose the option of landing with a tailwind, resulting in a steep, unstable approach.

- The final descent was initiated beyond the missed approach point and, combined with the 14-knot tailwind, resulted in the aircraft remaining above the desired 3-degree descent path.

- Neither pilot heard the ground proximity warning system warnings; both were focused on landing the aircraft to the exclusion of other indicators that warranted alternative action.

- During the final approach, the aircraft was unstable in several parameters. This instability contributed to the aircraft being half-way down the runway with excessive speed and altitude.

- The aircraft was not in a position to land and stop within the confines of the runway, and a go-around was initiated from a low-energy landing regime.

- The captain possibly eased off on the control column in the climb due to the low airspeed. This, in combination with the configuration change at a critical phase of flight [NOTE: gear retracted and flaps set to the ¼ position setting], as called for in the company procedures, may have contributed to the aircraft’s poor climb performance.

- A rate of climb sufficient to ensure clearance from obstacles was not established, and the aircraft collided with terrain.

- The infant passenger was not restrained in a child restraint system, nor was one required by regulations. The infant was ejected from the mother’s arms during the impact sequence, and contact with the interior surfaces of the aircraft contributed to the fatal injuries.

TSB Findings as to Risk

- If instrument approaches are conducted without reference to an approach chart, there is a risk of weakened situational awareness and of error in following required procedures, possibly resulting in the loss of obstacle clearance and an accident.

- If additional contingency fuel is not accounted for in the aircraft weight, there is a risk that the aircraft may not be operated in accordance with its certificate of airworthiness or may not meet the certified performance criteria [NOTE: it was custom and practice to carry unmanifested extra fuel – 200lb in this case].

- If Transport Canada crew resource management (CRM) training requirements do not reflect advances in CRM training, such as threat and error management and assertiveness training, there is an increased risk that crews will not effectively employ CRM to assess conditions and make appropriate decisions in critical situations. [NOTE: CRM training is not required in Canada for this type of operation]

- If a person assisting another is seated next to an emergency exit, there is an increased risk that the use of the exit will be hindered during an evacuation.

- If a person holding an infant is seated in a row with no seat back in front of them, there is an increased risk of injury to the infant as no recommended brace position is available.

- If young children are not adequately restrained, there is a risk that injuries sustained will be more severe.

- If a lap-held infant is ejected from its guardian’s arms, there is an increased risk the infant may be injured, or cause injury or death to other occupants.

- If more complete data on the number of infants and children travelling by air are not available, there is a risk that their exposure to injury or death in the event of turbulence or a survivable accident will not be adequately assessed and mitigated.

- If temperature corrections are not applied to all altitudes on the approach chart, there is an increased risk of controlled flight into terrain due to a reduction of obstacle clearance.

- If the missed approach point on non-precision instrument approaches is located beyond the 3-degree descent path, there is an increased risk that a landing attempt will result in a steep, unstable descent, and possible approach-and-landing accident.

- If there is not sufficient guidance in the standard operating procedures, there is a risk that crews will not react and perform the required actions in the event that ground proximity warning system warnings are generated.

- If standard operating procedures, the Airplane Flight Manual and training are not aligned with respect to low-energy go-arounds, there is a risk that crews may perform inappropriate actions at a critical phase of flight.

- If non-compliant practices are not identified, reported, and dealt with by a company’s safety management system, there is a risk that they will not be addressed in a timely manner.

- If Transport Canada’s oversight is dependent on the effectiveness of a company’s safety management system’s reporting of safety issues, there is a risk that important issues will be missed.

Observation

It is remarkable that a generation after the first CRM training, some passenger aircraft can operate within Canada without the crew having CRM training.

UPDATE 22 June 2017: A Canadian Parliament Committee issued a report to the federal government with 17 recommendations, aimed at enhancing aviation safety in Canada. The Standing Committee on Transport, Infrastructure and Communities heard 47 witnesses and received 11 briefs, leading to a report with 17 safety recommendations. These included:

- That the implementation of a Safety Management System becomes mandatory for all commercial operators, including the air taxi sector.

- That Transport Canada:

a. establish targets to ensure more on-site safety inspections versus Safety Management System audits;

b. use poor results from Safety Management System audits (including whistleblower input) as a ‘flag’ for prioritizing on-site inspections;

c. Review whistleblower policies to ensure adequate protection for people who raise safety issues to foster open, transparent and timely disclosure of safety concerns. - That the government make sure that Safety Management Systems are accompanied by an effective, properly financed, adequately staffed system of regulatory oversight: monitoring, surveillance and enforcement supported by sufficient, appropriately trained staff.

- That Transport Canada review all training processes and training materials for civil aviation inspectors to ensure they have the resources to perform their duties effectively.

We have recently discussed another TSB report on a fatal landing accident with the same aircraft type: Metro III: Propulsion System Malfunction + Inappropriate Crew Response

UPDATE 17 July 2017: TSB CRM/ADM recommendation stemming from 1998 airplane crash ‘still active’

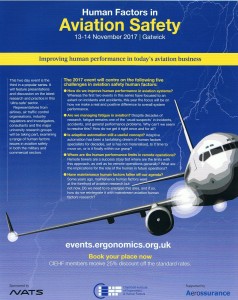

Aerossurance is pleased to be supporting the annual Chartered Institute of Ergonomics & Human Factors’ (CIEHF) Human Factors in Aviation Safety Conference for the third year running. We will be presenting for the second year running too. This year the conference takes place 13 to 14 November 2017 at the Hilton London Gatwick Airport, UK with the theme: How do we improve human performance in today’s aviation business?

Recent Comments