Consultants & Culture: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly

At Aerossurance we believe culture and leadership are critical to business performance. A 2016 Deloitte research report showed 86% and 89% of executives rate these as important priorities.

Organisations are however often tempted by offers of ‘diagnoses’ from consultants promising to diagnose their culture or leadership and by implication, prescribe a ‘cure’. There is something soothing in the idea that your organisation’s problems can be cured as easily as visiting a doctor.

However, General Practitioners often match symptoms to off-the-shelf remedies in consultations lasting minutes, then adjusting if the symptoms persist. Similarly, there is no equivalent of a hospital monitor to plug into an organisation.

Internationally renowned social psychologist Professor Edgar Schein, author of the highly influential Organizational Culture and Leadership, has commented that in his view, “simple culture diagnoses and cultural change fixes rarely accomplish what the clients want” (see Humble Consultanting p25). That’s because Schein contends, “organisational problems are increasingly complex, messy and unstable” and over reliance on supposed diagnostic tools “will at minimum waste time and at a maximum do unanticipated harm” (p172). He believes that while culture can be described and understood, it can’t be quantified.

Supporting this thinking, in a Health and Safety Executive (HSE) report from 2000 that proposed a safety culture maturity model, the authors cautioned their model was “provided to illustrate the concept and it is not intended to be used as a diagnostic instrument”.

Large consultancies like structured diagnostic tools because not only because they can be marketed as unique trade marked Intellectual Property but also because they can be applied by less skilled junior staff, matching symptoms to a limited number of existing off-the-self solutions. Some of these so-called tools are merely audit check lists re-branded to fool the gullible into premium fees. While some consultants promise neat solutions using proprietary tools:

…the most important work by the consultant is to help the client understand the messiness of the problem…[p179]

…and apply focused solutions that match the client’s real needs. As said elsewhere:

There are few management skills more powerful than the discipline of clearly articulating the problem you seek to solve before jumping into action.

However, a 2013 survey of 42 FTSE CEOs, 56 other CEOs and 62 C-level exeutives (chairman, presidents, principles, and board members in the UK found that 52% of them believed consultants fail to deliver on culture change programmes.

Faux-consultancies that are really a front for training providers for example will jump to make training the preferred action irrespective of the true client need or the most effective and efficient possible solutions. Liza Taylor comments that: Culture Change is Not About Navel Gazing:

…addressing culture is extremely important for business success however organizations need to be informed about whether they will actually get measurable performance results from the approach that is being suggested. Don’t be fooled…an approach that sounds like an interesting behavioral experiment or a snazzy tech solution is not usually a good one.

Sociologist Prof Diane Vaughan, whose seminal work The Challenger Launch Decision lead to her involvement in the Columbia Accident Investigation Board (CAIB), conducted under Admiral Hal Gehman, does make the point that “cultural blind spot” can exist where “insiders are unable to identify the characteristics of their own workplace structure and culture that might be causing problems”. Rather than surveys and focus groups, as a counter-measure she recommends immersing ethnographically trained researchers into organisations. This is the antithesis of using simplistic off the shelf diagnostic tools.

Edgar Schein on Consultancy

Schein describes his own learning from an earlier failed consultancy project to help an engineering company improve:

…we failed in almost every possible way. We never spoke to [the senior managers who commissioned the project] before launching the interviews [with the staff], so we had no idea what their goals or hidden agendas might have been.

They were…strangers to us…. We went into the interviews with no sense of who the client really was, what problems were being solved. or even what ‘improving’ meant. We were arrogant enough to believed we knew…

We focused on being ‘good scientists’…’gathering data’. We never knew how the project connected to the business problems the organisation was trying to address. We had the illusion that our careful diagnoses and recommendations spoke for themselves! I learned for the first time that… diagnosing organisations and cultures for its own sake is not helpful.

We should have not have been surprised that our feedback meeting…was stiff, formal and unproductive. (p46-47)

In another case, when he observed a team of management consultants at work Schein learnt:

…clients already know a lot of what outsiders bring to them… (p63)

Ironically when examining culture, the failure to enact recommendations is often due to:

…incompatibility between what the existing culture will allow and what the recommended solution is. An organisation can only do what is consistent with its culture… (p64)

Schein goes on to describe a case where he adopted the role of cultural ‘doctor’ and was shot down in flames by the management team who strongly disagreed with his analysis:

I resolved that,..when culture was involved, I would help the insiders diagnose themselves but would never again fall into the trap of telling a client about its own organisation. (p137)

In a far more successful project he helped coach a team of young engineers to solve an organisational problem:

I am constantly surprised at how often consultants grab at problems and own them, when it would be both more efficient and valid to turn the problems back to the organisation, take on the role of the humble consultant, and coach the organisation members… (p161)

Schein also commented that the young engineers were far more savvy at working out what solutions would get accepted. He also observed that his role of coaching was more fun than “deciphering the cultural content myself”. (p162)

I had by now learned…that a cultural diagnosis works best when done by insiders…in connection with a concrete problem they are trying to solve. (p162)

Its worth revisiting the wise words of Bill Voss, the then President of the Flight Safety Foundation (FSF), in 2012:

Back when the international standards for SMS were signed out at ICAO, we all knew we were going to launch a new industry full of consultants. We also knew that all these consultants couldn’t possibly know much about the subject and would be forced to regurgitate the ICAO guidance material that was being put out.

It was obvious that the process people dealing with ISO and QMS would embrace the concept of SMS and treat it as another process exercise.

It was also clear that regulators were going to have a very hard time evaluating an SMS and would be forced to reduce the concept to a series of checklists.

Many well-meaning operators have worked themselves into a position where they are spending lots of time and money, but are not necessarily getting the intended results.

Prof Dominic Swords, author of the 2013 study of 160 UK executives mentioned earlier, says:

The risk is that the company becomes dependent on the management consultancy relationship and each time a new change is needed the consultancy needs to be used. This does not develop a selfmanaged ‘change-enabled’ business which is a key characteristic of successful companies that need to operate in this new global era of change, innovation and uncertainty.

One company promotes a complex 22 element SMS model in their consulting business but has been roundly condemned for poor safety performance in their manufacturing business. We do wonder if organisational culture and safety leadership will go a similar way. One of our clients recently complained how they had become fed up being offered diagnostics by other consultants and wanted practical advice and assistance to actually improve.

UPDATE 25 February 2017: Furthermore it is very easy to fall for the fundamental attribution error and attribute every problem to ‘culture’ or ‘leadership’ when marketing cultural or leadership diagnoses: See Organizational Culture as Lazy Sensemaking

Schein emphasises the importance of actually being committed to helping clients and caring about their performance. This is distinct from business development, marketing canned solutions and only caring about your own financial performance. He goes on to say that this may mean doing less then the customer originally requested when there is a better way.

Examples of Bad Consultancy Practice

At a December 2016 UK CAA seminar on Safety Culture we were invited to discuss safety leadership. Our view is that ‘leadership’ is not about a person’s position per se but an activity and competence related to the motivation and influence of others (including the organisation’s culture).

We see leadership as distinct from ‘management’ (of information and resources), though both are vital for safety performance. We examined the marketing material for one proprietary ‘safety leadership diagnostic’ that included indicators such as:

- Safety is discussed in the boardroom

- Executing a well-defined safety strategy

- There are clear accountabilities for safety

Examining these in detail:

- Safety is discussed in the boardroom: Talk is cheap(!) and only talking amongst the board has limited influence on the behaviours of others in a large company. Leading by example is more than a phrase, its a sign of the importance of observable leadership behaviour.

- Executing a well-defined safety strategy: That’s a good thing, as long as the strategy defined is a good one(!), but its good safety management and not directly indicative of leadership and its influence on others.

- There are clear accountabilities for safety: This may be relevant, but only if they explicitly include leadership activities and competencies.

Embarking on a flawed diagnostic approach is likely to squander an opportunity to improve safety leadership.

We helped resolve the fallout of another consultancy’s safety culture project. They had sold an on-line survey, followed by focus groups. They initially didn’t supply any results from the on-line survey in their report, making the weak excuse that it was only intended to help plan their focus groups. When supplied, 50% of the free text ‘final comments’ submitted by survey participants queried the relevance and phrasing of the survey questions! There was also over 6 month delays before the report was completed. The report included a couple of unsubstantiated and foreseeably controversial comments that diverted management attention and had caused the customer’s safety efforts to temporarily stall.

We are aware of another consultancy who ran an overly long on-line employee safety survey but refused afterwards to analyse a significant number of the questions. They stated that in their ‘experience’ “those don’t add much value”. Their customer was rightly disappointed that time had been wasted answering such worthless questions!

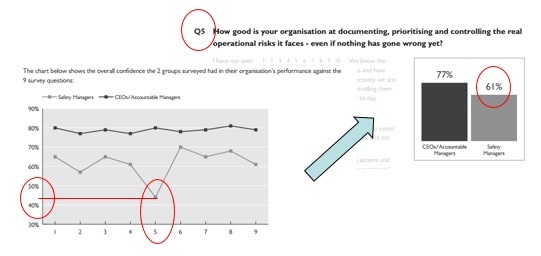

Meanwhile we recently read a publicly available survey that claimed to examine the “safety culture and performance” in one sector of the aviation industry. It was based on just 9 questions, comparing results from 35 CEOs/Accountable Managers and 15 Safety Managers.

Ignoring any concerns about the limits of the basic methodology and data set to draw the wide “evidence based” conclusions, it was immediately evident that data integrity had been lost when we noticed one obvious, large discrepancy (44% is shown on a summary chart in the introduction for Question 5 but this becomes 61% for that question when individual results are presented).

The authors however state that in their opinion (our emphasis added):

<<NAME OF CONSULTANCY>> has made every reasonable effort to ensure an accurate assessment of the survey results has been performed.

They do assign the following responsibility (which, as readers, we are discharging in this review of their ‘efforts’!):

Readers are responsible for assessing the relevance and accuracy of the content of this publication. <<NAME OF CONSULTANCY>> will not be liable for any loss, damage, cost or expense incurred or arising by reason of any person using or relying on information in this report.

In their long disclaimer they go on:

Any recommendations, opinions or findings stated in this report are based on the survey data. The report has been prepared…without any independent verification.

This might be subtle marketing for follow-on employee surveys, focus groups and proprietary ‘diagnostic tools’ in individual companies. Certainly the foreword to the report recommends “a more detailed and personalised diagnostic”. Potential customers have to consider the risk of their personalised report also containing corrupted and inexpertly analysed erroneous data.

In other cases, we are aware of focus groups being invited to do a ‘gap analysis’, facilitated by using cards bearing training courses titles.

In this case the consultants worked for a company whose prime business is training delivery, turning the focus group into a marketing exercise for which they could bill their customer for!

Often claims of scientific results are bogus. David Wilkinson, of the Oxford Review, shows that a widely cited claim in consultancy reports that there is a ‘70% failure in change projects’, used to encourage the need to contract expert support, has no scientific basis.

In particular the massaging of multiple point scoring into binary failure or success is noticeable as is the misrepresentation of personal observations as research data.

Diane Vaughan comments with frustration that:

On 16 December 2003, NASA Headquarters posted a Request for Proposals on its Web site for a cultural analysis to be followed by the implementation of activities that would eliminate cultural problems identified as detrimental to safety. Verifying the CAIB’s conclusions about NASA’s deadline-oriented culture, proposals first were due 6 January; then the deadline was extended by a meager 10 days.

Further, this survey was to be followed by plans to train and retrain managers to listen and decentralize and to encourage engineers to speak up. Thus, the Agency response would be at the interactional level only, leaving other aspects of culture identified in the CAIB report-such as goals; schedule pressures; power distribution across the hierarchy and between administrators, managers, and engineers, unaddressed.

And the Ugly

But the ugly is more about the toxic culture of some consultancies. In a BBC documentary last year a former management consultant with 30 years’ experience, explained how some big, growth orientated, consultancies have an aggressive business development strategy which involves a ‘problem-finding‘ approach:

“What you’re looking for is something that gives a big emotional shock to the client. We want to take them to what we call the ‘valley of death’.” The “valley of death” is the apocalypse scenario, telling the troubled organisation that if they don’t do something huge and expensive to change quickly, it’s going to fail, fast.

In fact very few organisations need major overhauls, most need modest ‘course corrections’. To make these sound more dramatic, and worthy of high fees, unscrupulous consultants will refer to“transformation programmes” for example.

Once we’ve taken them into the valley of death, it’s time for salvation. Now we go to the sunny uplands: it’s bad, it’s really bad, but working together we can save the situation.

A strategy of “land and expand”, finding things to ‘fix’ once you have your foot in the door is, depending on your perspective, either cynical exploitation or big consultancy business development. This is especially profitable for the unscrupulous when a client can be stuffed with cheap, junior consultants using those proprietary tools, who are learning on the job (if they are lucky), rather than really giving their customers true insight and charged at a high premium. That’s not Schein’s ‘helping consultant’ but more a ‘helping themselves consultant’.

One management consultancy has even been accused of building an espionage team to help themselves to data from competitors, including searching hotel meeting rooms for abandoned notes and documents!

In their book In Dangerous Company James O’Shea and Charlie Madigan describe “how consultants ran amok at Figgie International”. Figgie were a previously successful Ohio company, that in the pursuit of being a “world class manufacturer” was driven into the ground by consultants they had eventually owed $75 million to. O’Shea and Madigan comment that:

…consultants often have little to loose. If things work out they claim the credit. If not, they blame the employees or changes in management or a host of other problems.

The Independent has reported that:

The Cranfield School of Management studied 170 companies who had used management consultants, and it discovered just 36 per cent of them were happy with the outcome – while two thirds judged them to be useless or harmful. A medicine with that failure-rate would be taken off the shelves.

Footnote

Using consultants can be appropriate in particular circumstances. It is just vital to choose wisely and make sure you engage honest, professional, competent and experienced consultants who are committed to helping you, not helping themselves!

For those who work in the field of safety its also worth remembering the words of Brian Appleton of ICI (a company with a long history of pioneering process safety), an independent specialist Assessor to Lord Cullen‘s Piper Alpha Public Inquiry:

Safety is not an intellectual exercise to keep us in work. It is a matter of life and death; and it is the sum of our individual contributions to safety management that determine whether the people we work with live or die. On Piper, on 6th July 1988, they died.

At Aerossurance that’s something we don’t forget. Some consultancies boast they are world leaders. At Aerossurance our mission is to use our skills and expertise to help our customers be world leaders. Also see our past article: Coaching and the 70:20:10 Learning Model – Beyond Training

UPDATE 20 February 2017: 20 Organizational Culture Change Insights from Edgar Schein: A thorough interview with an organizational culture pioneer:

UPDATE 1 March 2017: Safety Performance Listening and Learning – AEROSPACE March 2017

Organisations need to be confident that they are hearing all the safety concerns and observations of their workforce. They also need the assurance that their safety decisions are being actioned. The RAeS Human Factors Group: Engineering (HFG:E) set out to find out a way to check if organisations are truly listening and learning.

The result was a self-reflective approach to find ways to stimulate improvement. See also: Why Leaders Who Listen Achieve Breakthroughs

UPDATE 4 March 2017: On an allied topic that also highlights the dangers of simplistic analysis: “Poor Communication” Is Often a Symptom of a Different Problem

…when you ask someone questions about how they feel about their workplace, people can answer that pretty readily… When you ask for more specific information about what is making them feel good or bad, though, people often grope around…

…it’s important to understand the limitations of people’s ability to report what is bothering them, whether it’s in a one-on-one conversation or in a feedback survey.

When you ask people a question, they typically want to give an answer. How good that answer is, though, depends on what access people have to the information that forms the basis of the answer. Most of us do a pretty lousy job of figuring out what’s actually bothering us.

Ultimately, it is important to remember that criticisms of broad topics like communication are a symptom, not a diagnosis. From there, it is crucial to examine complaints more closely to determine what the solutions might be.

UPDATE 12 April 2017: See our article: Leadership and Trust

UPDATE 25 May 2017: What makes change harder or easier:

Before you adopt any popular new management approach, it pays to analyze the implicit values embedded in it. Then ask yourself: How well will those values fit our existing organizational culture?

UPDATE 30 May 2017: More of the ugly: Why People With The Title “Thought Leader” Rarely Are. The same for companies that feel they have to advertise they are ‘world leaders’. Plus remember folks: you lead people not thoughts (unless you mean you just thought about leadership and didn’t!).

UPDATE 23 November 2017: Even more ugly: From inboxing to thought showers: how business bullsh!t took over. This article doesn’t just discuss meaningless jargon used to give an “impression of expertise” (as brilliantly portrayed in BBC’s self-satirising mockumentary W1A (video) and a quarter century earlier by character Gus Hedges, chief executive of fictitious GlobeLink News, in Channel 4’s newsroom comedy Drop the Dead Donkey). It also discusses Pacific Bell’s Kroning misadventure with out of control consultants (only abandoned when regulators refused to let them pass the spiralling cost to customers). As the Guardian article says:

As companies have become increasingly ravenous for the latest management fad, they have also become less discerning. Some bizarre recent trends include equine-assisted coaching (“You can lead people, but can you lead a horse?”) and rage rooms (a room where employees can go to take out their frustrations by smashing up office furniture, computers and images of their boss).

A century of management fads has created workplaces that are full of empty words and equally empty rituals. We have to live with the consequences of this history every day.

Manufacturing hollow change requires a constant supply of new management fads and fashions. Fortunately, there is a massive industry of business bullsh!t merchants who are quite happy to supply it. For each new change, new bullshi!t is needed.

UPDATE 27 November 2017: “The importance of having a strong corporate culture has been well documented”. But according to a research report by INSEAD, Board Agenda and Mazars:

…a worryingly small number of board directors are actually clear about what they desire from their corporate cultures. Even more alarmingly, the very discussion of corporate culture isn’t getting the attention it deserves at board level.

Perhaps the lack of clarity is driven by the Bad and the Ugly…

UPDATE 24 December 2017: The Leader’s Guide to Corporate Culture

UPDATE 1 May 2018: Management Consultants: The Smartest Guys in the Room?

Leadership and management skills are fundamental for military officers. Management especially seems to be increasingly important the more senior you get. Yet a culture exists whereby management consultants are quickly and readily hired.

[Their] impartiality is, however, questionable; they are not ultimately driven by their goodwill towards the Army. Individuals no doubt care deeply about doing a good job, but they are still formally incentivised by maximising profit. This is most effectively done through delivering follow-on work. A perverse (although understandable) incentive, whereby one project leads to another and another. At the start and throughout a project, the senior consultancy leaders will be pressurising their teams to identify follow-on pitches, to set-up side conversations and prompt senior Officers and MoD staff to recognise the critical need for…more consultancy. Thus, it is not in the teams interests to simply, directly, and conclusively answer a problem. It is instead to ‘farm’ the client for further project revenue.

UPDATE 20 September 2018: Changing the Conversations That Kill Your Culture

UPDATE 6 November 2018: If Your Employees Aren’t Speaking Up, Blame Company Culture

UPDATE 4 February 2019: A recent survey shows that employees feel less positive about their workplace culture than their employers. Five actions are proposed:

- Address where your culture and your strategy clash: “No culture is all good or all bad. Every culture has emotional energy within it that can be leveraged” says Jon Katzenbach.

- Change your listening tours: “It takes more than ordinary listening to get a true understanding of the culture at your organization. Instead, challenge and foster healthy debate and real feedback from people across departments and across levels. Connect with people who are emotionally astute and who have insight into what people care about most.”

- Identify the “critical few” behaviors that will shift your culture: “Cultures don’t change quickly, but a disciplined focus on these “critical few” can accelerate and catalyze a purposeful evolution. As people begin to adopt the behaviors, take time to recognize and reward those people for focusing on those behaviors, too.”

- Step into the “show me” age: “Right away, do something that’s visible and concrete. If it succeeds and sends a positive message, repeat it–early and often. Then, encourage others to do the same. When your people see you leading by example, they’re more likely to follow suit.”

- Commit to culture as a continual, collaborative effort: ” …42% of respondents believe that their organization’s culture has remained static for the last five years. 23% of employees report that leaders of their organizations have tried culture change or evolution of some form, but acknowledge that the efforts resulted in no discernible improvements. Influencing culture is hard, and most leaders declare victory too soon. It can’t be a “one-off” project, nor can it be implemented top-down. Prepare to persevere through obstacles if you want long-term, sustainable change. The more ambitious the effort, the more time and more input from people at all levels it will demand”.

UPDATE 26 February 2019: You can’t benchmark culture: “Your company’s ideal behavioral strengths are unique, and shouldn’t be borrowed or copied — not even from a high-performance enterprise”.

UPDATE 26 March 2019: Closing the Culture Gap: Linking rhetoric and reality in business transformation.

First and foremost, you must identify your organization’s “critical few” traits: the core attributes that are unique and characteristic to it, that resonate with employees, and that can help spark their commitment. Next, you develop the critical few behaviors that, if executed repeatedly by more people more of the time, will move the habitual ways of working into better alignment with the organization’s strategic and operational objectives. These behaviors should be tangible, repeatable, observable, and measurable. They are critical because they will have a significant impact on business performance when exhibited by large numbers of people. They are few because people can remember and change only three to five key behaviors at one time.

The authors of this article recommend leaders:

- ground goals in what’s possible

- tune in to emotions

- empower AILs (authentic informal leaders) and (obviously!)…

- displaying behaviours consistently themselves

UPDATE 20 April 2019: Conform to the Culture Just Enough. If you have been newly appointed to a management position:

Unless it’s a turnaround in which the intent is to radically transform a dysfunctional culture, your success will hinge on your ability to conform just enough. If you conform too much, you’ll miss opportunities to influence positive change and make a difference. And if you don’t conform enough, your efforts will be ignored or rebuffed, and eventually you’ll burn out or be rejected.

UPDATE 10 June 2019: Want your people to achieve more than you thought was possible? Prioritise psychological safety and employee engagement

UPDATE 11 June 2019: Scaling Culture in Fast-Growing Companies:

Define culture in terms of clear, observable behaviors. Organizational learning is a social process, and employees learn by observing others. But abstract values such as “innovation,” “respect,” or “drive” can mean different things to different people.

UPDATE 20 June 2019: The Wrong Ways to Strengthen Culture According to one survey:

Each year companies spend $2,200 per employee, on average, on efforts to improve the culture (much of the money goes to consultants, surveys, and workshops)—but only 30%…report a good return on that investment.

UPDATE 14 December 2019: A “culture of safety” is lacking at the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) “according to a scathing report by three outside experts“.

UPDATE 3 February 2021: Building a culture of learning at work: How leaders can create the psychological safety for people to constantly rethink what’s possible.

The foundation of a learning culture is psychological safety — being able to take risks without fear of reprisal. Evidence shows that when teams have psychological safety, they’re more willing to acknowledge their own mistakes and figure out how to prevent them moving forward. They’re also more comfortable raising problems and exploring innovative solutions.

The standard advice for managers on building psychological safety is to model openness and inclusiveness: Ask for feedback on how you can improve, and people will feel it’s safe to take risks. In multiple companies, we randomly assigned some managers to ask their teams for constructive criticism.Over the following week, their teams reported higher psychological safety, but as we anticipated, it didn’t last. Some managers who asked for feedback didn’t like what they heard and got defensive. Others found the feedback useless or felt helpless to act on it, which discouraged them from continuing to seek feedback and their teams from continuing to offer it.

Another group of managers took a different approach, one that had a less immediate impact in the first week but led to sustainable gains in psychological safety a full year later. Instead of asking them to seek feedback…we advised them to tell their teams about a time when they benefited from constructive criticism and to identify the areas that they were working to improve now.

By admitting some of their imperfections out loud, managers demonstrated that they could take it — and made a public commitment to remain open to feedback. They normalized vulnerability, making their teams more comfortable opening up about their own struggles. Their employees gave more useful feedback, because they knew where their managers were working to grow.

Creating psychological safety can’t be an isolated episode or a task to check off on a to‑do list.

And certainly not a consultant popping in on a bungee chord!!

Recent Comments