Germanwings: Psychiatry, Suicide and Safety

The French Bureau d’Enquêtes et d’Analyses (BEA) has issued their report into the loss of Germanwings Airbus A320 D-AIPX and 150 lives in the French Alps on 24 March 2015, which was due to the actions of the Co-Pilot. Below we focus on the highlights from the 110 page report.

The Co-Pilot

The BEA summarise the career of the 27 year old Co-Pilot Andreas Lubitz as follows:

-

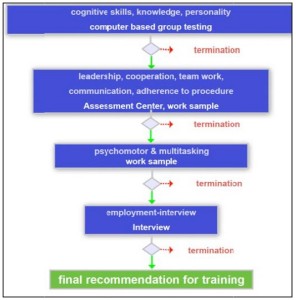

between January and April 2008, he took entry selection courses with Lufthansa Flight Training (LFT);

-

on 1 September 2008, he started his basic training at the Lufthansa Flight Training Pilot School in Bremen (Germany);

-

on 5 November 2008 he suspended his training for medical reasons;

-

on 26 August 2009 he restarted his training;

-

on 13 October 2010, he passed his ATPL written exam;

-

from 8 November 2010 to 2 March 2011, he continued his training at the Airline Training Centre in Phoenix (Arizona, USA);

-

from 15 June 2011 to 31 December 2013, he was under contract as a flight attendant for Lufthansa while continuing his Air Transport pilot training;

-

from 27 September to 23 December 2013, he took and passed his A320 type rating at Lufthansa in Munich (Germany);

-

on 4 December 2013, he joined Germanwings [a Lufthansa subsidiary];

-

from 27 January 2014 to 21 June 2014, he undertook his operator’s conversion training including his line flying under supervision at Germanwings;

-

on 26 June 2014, he passed his proficiency check and was appointed as a co-pilot;

- on 28 October 2014, he passed his operator proficiency check.

The BEA say:

In 2008, 384 pilots out of a total of 6,530 applicants were selected to start training at the LFT centre.

The co-pilot…was the holder a class 1 medical certificate that was first issued in April 2008 and had been revalidated or renewed every year.

In August 2008, the co-pilot started to suffer from a severe depressive episode without psychotic symptoms. During this depression, he had suicidal ideation, made several ‘no suicide pacts’ with his treating psychiatrist and was hospitalized. He undertook anti-depressive medication between January and July 2009 and psychotherapeutic treatment from January 2009 until October 2009. His treating psychiatrist stated that the co-pilot had fully recovered in July 2009.

Since July 2009, this medical certificate had contained a waiver…This waiver stated that it would become invalid if there was a relapse into depression.

The copilot had had to pay 60,000 € to finance his part of the costs of his training at LFT [150,000€ in total]. He had taken out a loan for about 41,000 € to do so. A Loss-of-License (LOL) insurance contracted by Germanwings existed and would have provided the co-pilot with a one-time payment of 58,799 € in case he had become permanently unfit to fly in the first five years of employment.

This type of insurance is contracted for all Lufthansa and Germanwings pilots until they reach 35 years of age and complete 10 years of service.

The co-pilot did not have any additional insurance that would cover for potential future loss of income in case of unfitness to fly. In an e-mail he wrote in December 2014, he mentioned that having a waiver attached to his medical certificate was hindering his ability to get such an insurance policy.

The BEA explain that:

Pilots must declare on their class 1 application form whether they have or have ever had any history of psychological or psychiatric trouble of any sort. The psychiatric assessment of pilots during medical certification is then performed through general discussion and by observing behaviour, appearance, speech, mood, thinking, perception, cognition and insight.

The depression episode experienced by the co-pilot in 2008 was correctly identified by the Lufthansa [Aeromedical centre] AeMC during the revalidation process of his class 1 medical certificate in April 2009. A waiver based on the assessment from a psychiatrist allowed the pilot to hold a class 1 medical certificate again in July 2009. Every year after that, his class 1 medical certificate was revalidated or renewed. All of the [Aeromedical Examiner] AMEs who examined him during that period were aware of the waiver and were informed of his medical history of depression.

In December 2014…the co-pilot started to show symptoms that could be consistent with a psychotic depressive episode. He consulted several doctors, including a psychiatrist on at least two occasions, who prescribed anti-depressant medication.

The Co-Pilot did not contact an AME between December 2014 and the accident.

In February 2015, a private physician diagnosed a psychosomatic disorder and an anxiety disorder and referred the co-pilot to a psychotherapist and psychiatrist. On 10 March 2015, the same physician diagnosed a possible psychosis and recommended psychiatric hospital treatment. A psychiatrist prescribed anti‑depressant and sleeping aid medication in February and March 2015. Neither…informed any… authority about the co-pilot’s mental state. Several sick leave certificates were issued…but not all of them were forwarded to Germanwings.

As part of the accident investigation:

The co-pilot’s medical file…was analysed in detail by a German expert in aviation medicine and a German psychiatrist. Their analysis was shared and discussed with a team of experts, formed by the BEA, and composed of British aeromedical and psychiatric experts as well as French psychiatrists. The limited medical and personal data available to the safety investigation did not make it possible for an unambiguous psychiatric diagnosis to be made.

In particular an interview with the co-pilot’s relatives and his private physicians was impossible, as they exercised their right to refuse to be interviewed by the BEA and/or the BFU.

However, the majority of the team of experts consulted by the BEA agreed that the limited medical information available may be consistent with the co-pilot having suffered from a psychotic depressive episode that started in December 2014, which lasted until the day of the accident. Other forms of mental ill-health cannot be excluded and a personality disorder is also a possibility.

The BEA go on to say:

During [the Co-Pilot’s] training and recurrent checks, his professional level was judged to be above standard by his instructors and examiners.

None of the pilots or instructors interviewed during the investigation who flew with him in the months preceding the accident indicated any concern about his attitude or behaviour during flights.

No action could have been taken by the authorities and/or his employer to prevent him from flying on the day of the accident, because they were informed by neither the co-pilot himself, nor by anybody else, such as a physician, a colleague, or family member.

The Accident Flight

The aircraft:

…was programmed to undertake scheduled flight 4U9525 between Barcelona (Spain) and Düsseldorf (Germany), with the callsign GWI18G. Six crew members (2 flight crew and 4 cabin crew) and 144 passengers were on board.

During that flight:

…the co-pilot waited until he was alone in the cockpit. He then intentionally modified the autopilot settings to order the aeroplane to descend. He kept the cockpit door locked during the descent, despite requests for access made via the keypad and the cabin interphone. He did not respond to the calls from the civil or military air traffic controllers, nor to knocks on the door.

Security requirements that led to cockpit doors designed to resist forcible intrusion by unauthorized persons made it impossible to enter the flight compartment before the aircraft impacted the terrain in the French Alps.

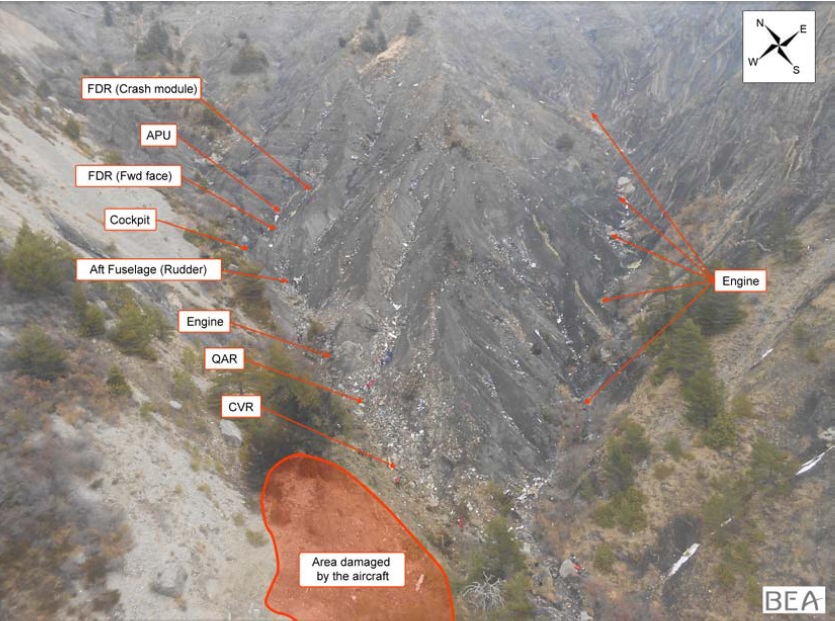

The accident site was located in mountainous terrain, in the municipality of Prads‑Haute-Bléone (04) 1,550 m above sea level(12). The wreckage was fragmented with a large amount of debris spread over an area of 4 hectares in a sloping rocky ravine. The largest parts of the aeroplane were about 3 to 4 metres long.

Conclusions

The BEA concluded that:

…the process for medical certification of pilots, in particular self-reporting in case of decrease in medical fitness between two periodic medical evaluations, did not succeed in preventing the co-pilot, who was experiencing mental disorder with psychotic symptoms, from exercising the privilege of his licence.

They comment that:

The calculation of the acceptable risk for pilots’ in-flight incapacitation is based on the ‘1% rule’ which relies on the presence of a second pilot to take over all the flight duties in the event of the incapacitation of the other pilot.

…mental incapacitation should not be treated the same way as physical incapacitation because the risks they generate cannot be mitigated in the same way by the two‑pilot operation principle. Therefore, the target of acceptable risk for non-detection of a mental disorder that may result in a voluntary attempt to put the aircraft into an unsafe condition should be more ambitious than the one usually accepted for ‘classical’ physical incapacitation risk. If one follows the calculation methodology developed in ICAO’s Manual of Civil Aviation Medicine (Doc 8984) and described in paragraph 1.17.2, a quantitative target should be lower by at least two orders of magnitude, or 0.01%.

They go on:

…review of previous accidents and incidents confirms that actions by a mentally disturbed pilot to purposely crash the aircraft could sometimes not be averted by the other pilot. The review of incidents also shows that the psychological incapacitation of a pilot, even if it does not lead to a deliberate attempt to crash the aircraft, is difficult to control by other crew members and can lead to an unsafe situation.

Managing the risk of having an unfit pilot on board is partially based on the safety assumption that the pilot will self-declare his decrease in medical fitness.

In spite of this awareness of unfitness to fly and his medication, the co-pilot did not seek any advice from an AME nor did he inform his employer.

They identify three factors might have contributed to the Co-Pilot’s failure to self-declare.

First, the co-pilot, while suffering from a disease with symptoms of psychiatric disorder, possibly a psychotic depressive episode, had altered mental abilities with a probable loss of connectedness with reality and therefore a lack of discernment.

Secondly, the financial consequences of losing his licence would have reached a total of 60,000 €. In addition that would have caused the loss of his income, which was not covered by his loss-of-licence insurance. Moreover, he had not yet fulfilled the conditions to have his full coverage paid for by the airline.

Thirdly, the consequence of losing his license would tend to destroy his professional ambitions. Like most professional pilots, the decision to become an airline pilot was probably not solely motivated by the desire to earn a salary but also by a passion for flying aircraft, and also by the positive image conveyed by this profession.

The BEA say:

The safety assumption stating that ‘the pilot will self-declare his unfitness’ failed in this event.

The robustness of self-declaration is also questionable when the negative consequences for the pilot seem higher for him/her than the potential impact of a lack of declaration.

In order to disclose concerns over mental illness, pilots need to overcome the stigma that is attached to mental illness, and the prospects of losing their medical certification and therefore their positions as pilots.

A number of airlines, including Germanwings, have psychological support programmes available to their crews to self-report medical conditions, including emotional and mental health issues, and then seek assistance to find a solution. In theory, these programs, staffed by peers, provide a ‘safe zone’ for pilots by minimizing career jeopardy and the stigma of seeking mental health assistance. The idea is to foster trust in pilots by setting up a non-threatening and confidential environment, with the assurance that fellow pilots are there to help, and do not intend to apportion blame or responsibility.

The BEA discuss how in some other industries alternative employment is offered when personnel are unfit to continue in a safety crtical role, though they note that this normally results in a drop in income. They also report that regulators in Australia, the UK, Canada and the USA allow certain treatment options:

Studies have shown that having programmes allowing pilots to take anti-depressants, under specific conditions and with close medical supervision, is beneficial to flight safety.

The BEA note that:

On the one hand, German regulations contain specific provisions to punish doctors violating medical confidentiality, including occupational consequences and imprisonment up to one year. On the other hand, the German criminal code has very general provisions stating that any person who acts to avert an imminent danger does not act unlawfully, if the act committed is an adequate means to avert the danger and if the protected interest substantially outweighs the one interfered with.

In this case medical confidentiality won.

The BEA determined the cause of the accident to be:

The collision with the ground was due to the deliberate and planned action of the co-pilot who decided to commit suicide while alone in the cockpit. The process for medical certification of pilots, in particular self-reporting in case of decrease in medical fitness between two periodic medical evaluations, did not succeed in preventing the co-pilot, who was experiencing mental disorder with psychotic symptoms, from exercising the privilege of his licence.

The BEA conclude the following may have contributed to the failure of the medical evaluation process:

-

the co-pilot’s probable fear of losing his right to fly as a professional pilot if he had reported his decrease in medical fitness to an AME;

-

the potential financial consequences generated by the lack of specific insurance covering the risks of loss of income in case of unfitness to fly;

-

the lack of clear guidelines in German regulations on when a threat to public safety outweighs the requirements of medical confidentiality.

Additionally:

Security requirements led to cockpit doors designed to resist forcible intrusion by unauthorized persons. This made it impossible to enter the flight compartment before the aircraft impacted the terrain in the French Alps.

Safety Recommendations

The BEA has addressed eleven safety recommendations in 6 areas. On medical evaluation of pilots with mental health issues:

-

EASA require that when a class 1 medical certificate is issued to an applicant with a history of psychological/psychiatric trouble of any sort, conditions for the follow-up of his/her fitness to fly be defined. This may include restrictions on the duration of the certificate or other operational limitations and the need for a specific psychiatric evaluation for subsequent revalidations or renewals. [Recommendation FRAN‑2016‑011]

On routine analysis of in-flight incapacitation:

-

EASA include in the European Plan for Aviation Safety an action for the EU Member States to perform a routine analysis of in-flight incapacitation, with particular reference but not limited to psychological or psychiatric issues, to help with continuous re-evaluation of the medical assessment criteria, to improve the expression of risk of in-flight incapacitation in numerical terms and to encourage data collection to validate the effectiveness of these criteria. [Recommendation FRAN-2016-012]

-

EASA, in coordination with the Network of Analysts, perform routine analysis of in-flight incapacitation, with particular reference but not limited to psychological or psychiatric issues, to help with continuous re-evaluation of the medical assessment criteria, to improve the expression of risk of in-flight incapacitation in numerical terms and to encourage data collection to validate the effectiveness of these criteria. [Recommendation FRAN-2016-013]

To mitigate the consequences of loss of licence:

-

EASA ensure that European operators include in their Management Systems measures to mitigate socio-economic risks related to a loss of licence by one of their pilots for medical reasons. [Recommendation FRAN‑2016‑014]

-

IATA encourage its Member Airlines to implement measures to mitigate the socio-economic risks related to pilots’ loss of licence for medical reasons. [Recommendation FRAN-2016-015]

On anti-depressant medication and flying status:

-

EASA define the modalities under which EU regulations would allow pilots to be declared fit to fly while taking anti-depressant medication under medical supervision. [Recommendation FRAN-2016-016]

On the balance between medical confidentiality and public safety:

-

The World Health Organization [WHO] develop guidelines for its Member States in order to help them define clear rules to require health care providers to inform the appropriate authorities when a specific patient’s health is very likely to impact public safety, including when the patient refuses to consent, without legal risk to the health care provider, while still protecting patients’ private data from unnecessary disclosure. [Recommendation FRAN-2016-017]

-

The European Commission in coordination with EU Member States define clear rules to require health care providers to inform the appropriate authorities when a specific patient’s health is very likely to impact public safety, including when the patient refuses to consent, without legal risk to the health care provider, while still protecting patients’ private data from unnecessary disclosure. These rules should take into account the specificities of pilots, for whom the risk of losing their medical certificate, being not only a financial matter but also a matter related to their passion for flying, may deter them from seeking appropriate health care. [Recommendation FRAN-2016-018]

- Without waiting for action at EU level, the BMVI and the Bundesärztekammer (BÄK) edit guidelines for all German health care providers to: a) remind them of the possibility of breaching medical confidentiality and reporting to the LBA or another appropriate authority if the health of a commercial pilot presents a potential public safety risk. b) define what can be considered as ‘imminent danger’ and ‘threat to public safety’ when dealing with pilots’ health issues and c) limit the legal consequence for health care providers breaching medical confidentiality in good faith to lessen or prevent a threat to public safety. [Recommendation FRAN-2016-019 and FRAN-2016-020]

Promotion of pilot support programmes:

-

EASA ensure that European operators promote the implementation of peer support groups to provide a process for pilots, their families and peers to report and discuss personal and mental health issues, with the assurance that information will be kept in-confidence in a just‑culture work environment, and that pilots will be supported as well as guided with the aim of providing them with help, ensuring flight safety and allowing them to return to flying duties, where applicable. [Recommendation FRAN-2016-021]

This is not a fundamentally new problem in aviation. On 30 October 1959 DC-3 N55V of Piedmont Airlines crashed at Bucks Elbow Mountain, Virginia, killing 26 of the 27 occupants. Investigators of the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB), forerunner to the NTSB, found the Aircraft Commander had suffered from “serious emotional and mental stress episodes since 1953. He was under psychotherapy at the time of the accident” and ” likely taking Prozine in the period leading up to the accident, an antipsychotic medicine”. The CAB stated that the investigation “demonstrated the need for re-examination of the use of drugs that might affect the capabilities of a flight crew member” and “if a flight crew member’s personal situation demands tranquilizers he should be removed from flying status while on the drugs.”

See also: An Accident and its Impact on Crews, Operation and the Organization

We have previously written about: Psychological Screening of Flight Crew We have also discussed a report by the CHIRP Charitable Trust, who run the UK’s Confidential Human Factors Incident Reporting Programme (CHIRP). That highlighted reports received relating to an oil company changing its North Sea helicopter operator. During that contract change and the threat of redundancy CHIRP said:

The operator’s creditable efforts to mitigate the risks by encouraging pilots to stand themselves down if they felt unduly stressed were partially offset by pilots’ concerns that demonstrating weakness, particularly mental weakness, could jeopardise future employment prospects.

It is not enough to tell pilots that they should not report to work if they are not mentally focussed or stressed. A way must be found to generate the conditions in which pilots can do what they know to be correct without fear of long term disadvantage.

CHIRP then goes on to draw parallels with the Germanwings accident in relation to the challenges of relying on self-declaration.

UPDATE 15 April 2016: The accident report into the deliberate crash of LAM Embraer 190 C9-EMC in Namibia on 29 November 2013 has been issued. All 33 occupants died after the captain, left alone in the cockpit, commanded a rapid descent which culminated in a high-speed collision with terrain.

UPDATE 19 April 2016: Flight International have covered the C-9-EMC report. They note the investigators have not made any explicit safety recommendations relating on pilot medical checks in that case. They go on to highlight:

…that the captain had been through a number of difficult personal circumstances including the suicide of his son just nine months earlier.

UPDATE 20 April 2016: EASA have issued the terms of reference for the Rule Making Task (RMT.0700 Aircrew Medical Fitness) on implementation of the recommendations made by the EASA-led Germanwings Task Force. EASA has also organised a public conference 15-16 June 2016 in Cologne to update progress on their actions.

UPDATE 22 April 2016: Concern has been raised Air Transport Association of Canada over the lack of action by Transport Canada: Mental health screening for pilots ‘crack in the armour’ of Canadian airline safety

UPDATE 16 June 2016: The US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has issued a press release on recommendations of an Aviation Rulemaking Committee (ARC) comprised of aviation and medical experts. The FAA say:

In January, the FAA began enhanced training for Aviation Medical Examiners so they can increase their knowledge on mental health and enhance their ability to identify warning signs.

Airlines and unions will expand the use of pilot assistance programs. The FAA will support the development of these programs over the next year. These programs will be incorporated in the airline’s Safety Management Systems for identifying risk.

The FAA will work with airlines over the next year as they develop programs to reduce the stigma around mental health issues by increasing awareness and promoting resources to help resolve mental health problems.

The FAA will issue guidance to airlines to promote best practices about pilot support programs for mental health issues.

The FAA will ask the Aerospace Medical Association to consider addressing the issue of professional reporting responsibilities on a national basis and to present a resolution to the American Medical Association. Reporting requirements currently vary by state and by licensing and specialty boards

However:

The ARC’s experts did not recommend routine psychological testing because there was no convincing evidence that it would improve safety, which the Aerospace Medical Association also concluded…stating that in-depth psychological testing of pilots as part of routine periodic care is neither productive nor cost effective.

Instead, the FAA and the aviation community is embracing a holistic approach that includes education, outreach, training, and encourages reporting and treatment of mental health issues.

UPDATE 17 June 2016: The British Psychological Society (BPS) have a workshop in October 2016 on clinical skills for working with air crew, run by Professor Robert Bor.

UPDATE 28 June 2016: Steve Hull of RTI Forensics, discusses the topic “Do Airlines Really Understand Pilot Suicide?” in an RAeS lecture (available as a podcast).

UPDATE 21 July 2016: EASA has issued a further SIB on Minimum Cockpit Occupancy. EASA say:

CAT.OP.MPA.210 of Regulation (EU) No 965/2012 stipulates that flight crew members required to be on duty in the flight crew compartment shall remain at the assigned station, unless absence is necessary for the performance of duties in connection with the operations or for physiological needs, provided at least one suitably qualified pilot remains at the controls of the aircraft at all times.

In such cases, EASA recommends operators to assess the safety and security risks associated with a flight crew member remaining alone in the flight crew compartment.

EASA say this assessment should consider:

- the operator’s psychological and security screening policy of flight crews;

- employment stability and turnover rate of flight crews;

- access to a support programme, providing psychological support and relief to flight crew when needed; and

- ability of the operator’s management system to mitigate psychological and social risks.

If the assessment leads the operator to require two authorised persons in accordance with CAT.GEN.MPA.135 to be in the flight crew compartment at all times, operators should ensure that:

(a) the role of the authorised person, other than the operating pilot, in the flight crew compartment is clearly defined, considering that his/her main task should be to open the secure door when the flight crew member who left the compartment returns;

(b) only suitably qualified flight crew members are allowed to sit at the controls;

(c) safety and security procedures are established for his/her presence in the flight crew compartment (e.g. operation of the flight deck, specific procedure for entry, use of observer seat and oxygen masks, avoidance of distractions etc.);

(d) training needs are addressed and identified as appropriate;

(e) safety risks stemming from the authorised person leaving the passenger cabin are assessed and mitigated, if necessary; and

(f) resulting procedures are detailed in the Operations Manual and, when relevant, the related security reference documents.

UPDATE 16 August 2016: EASA has published a set of proposals to the European Commission for an update of the rules concerning pilots’ medical fitness:

These rules are contained in so-called Part-MED, which covers aviation safety rules related to the medical aspect and fitness of aircrews.

Released in a document known as an Opinion, these proposals introduce the following new requirements, among others:

- strengthening the initial and recurrent medical examination of pilots, by including drugs and alcohol screening, comprehensive mental health assessment, as well as improved follow-up in case of medical history of psychiatric conditions;

- increasing the quality of aero-medical examinations, by improving the training, oversight and assessment of aero-medical examiners;

- preventing fraud attempts, by requiring aero-medical centres and AMEs to report all incomplete medical assessments to the competent authority.

These proposals have been subject to consultation with all concerned stakeholders. They address relevant safety recommendations made after the Flight 9525 accident by the EASA-led Task Force, as well as by the French “Bureau d’Enquêtes et d’Analyses” (BEA).

The EASA Opinion (Opinion 09/2016) also includes a broader update of Part-MED, aimed at keeping the rules up-to-date with latest developments in the field of medicine and filling any gaps identified through the operational experience.

Next steps: The EASA Opinion will serve as the basis for a legislative proposal by the European Commission towards the end of 2016. To support the implementation of the new rules, EASA has prepared draft guidance material (so-called Acceptable Means of Compliance and Guidance Material – AMC/GM), annexed to the Opinion. The final AMC/GM will be published when the new rules have been adopted by the Commission. A further set of regulatory proposals in the area of Air Operations will follow before the end of the year.

UPDATE 9 December 2016: EASA have issued Opinion 14/2016 ‘Aircrew medical fitness – Implementation of the recommendations made by the EASA-led Germanwings Task Force on the accident of the Germanwings Flight 9525’. This Opinion proposes changes to the Air OPS implementing rules (IRs):

- Preventive measures such as:

- carrying out a psychological assessment of the flight crew before commencing line flying;

- enabling, facilitating and ensuring access to a flight crew support programme; and

- performing systematic drug and alcohol (D&A) testing of flight and cabin crew upon employment.

- Corrective and follow-up measures such as performing flight and cabin crew D&A testing:

- after a serious incident;

- after an accident;

- following a reasonable suspicion; and

- unannounced after rehabilitation and return to work.

- A complementary measure: mandatory random alcohol screening of flight and cabin crew within the ramp inspection programme to ensure an additional safety barrier.

UPDATE 15 December 2016: A study by the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health shows hundreds of pilots are suffering from depression.

UPDATE 2 March 2017: Mental health: IoD calls for ‘a little more conversation’ (click here to download a PDF of the IoD report).

UPDATE 17 March 2017: Jobs with highest risk of suicide for men and women revealed

UPDATE 18 March 2017: Discussing mental health issues from a military pilot perspective: When Good Pilots Go Bad

Meanwhile for practical information on on Setting Up and Running a Pilot Support programme, Core Aviation Psychology will be holding a workshop on Wednesday 12 April 2017 from 10.00 to 16.00 at the Crowne Plaza Hotel, Aberdeen Airport.

UPDATE 24 March 2017: Father of Germanwings suicide pilot Andreas Lubitz angers victims’ families as he protests son’s innocence

An emotional Günther Lubitz told a press conference in Berlin his son was not depressed or suicidal at the time of the 2015 tragedy… …he offered a new report commissioned by the family which picked holes in the official investigation and suggested a different sequence of events.

The report, by German journalist Tim van Beveran, claims the co-pilot:

…could have started a routine descent and then fallen unconscious at the controls…

UPDATE 5 April 2017: Aircrew Mental Health – Regulatory and Implementation Challenges

The current [Peer Support System] PSS regulations and implementation guidelines are an evolving project. As AOC holders gather experience and data over the coming years the knowledge base of ‘what works’ will grow. This growing knowledge base will inform and ‘tune’ the content and process of dealing positively with aircrew mental health issues going forward.

In effect the sector will do what it does so well – it will learn from a form of ‘on condition’ monitoring and that learning will be disseminated through civil aviation to benefit both the sector and the individual.

One key part of the challenge, if we view mental health as an operational risk, is the incidence base rate and severity in the population. We monitor engine performance and have scheduled airframe maintenance based on an understanding of the risk profiles that result from operational use. We resource our systems and procedures based on this understanding of the risk profile faced to mitigate it appropriately.

UPDATE 10 May 2017: EASA have published their safety recommendation response progress (catalogued in their Annual Safety Recommendations Review 2016).

UPDATE 7 December 2017: Aviation Personnel Mental Health and Wellbeing: Commissioned by the Professional Practice Board of the British Psychological Society in 2016, a group of expert aviation psychologists chaired by Professor Robert Bor developed a Position Paper on Aviation Psychology, with focus on the mental health and wellbeing of pilots and other aviation personnel.

UPDATE 26 May 2018: Pilot mental health care still facing ‘normalisation’ barriers said speakers at an RAeS conference on aircrew mental health, held in London on 24 May 2018.

UPDATE 30 September 2018: CAP1695: Pilot Support Programme – Guidance for Commercial Air Transport (CAT) Operators from UKCAA.

UPDATE 28 January 2019: Commander of Crashed Dash 8 Q400 in Nepal “Harboured Severe Mental Stress” Say Investigators

UPDATE 30 January 2019: There will be an RAeS conference on Aerospace Mental Health and Wellbeing 22-23 May 2019 in London.

UPDATE 24 March 2019: Unconfirmed press report: Allegedly suicidal pilot crashes into Botwana clubhouse in attempt to kill wife and friends (KA200 A2-MBM).

UPDATE 3 January 2020: Caring for Pilots (RAeS conference summary).

UPDATE 20 April 2020: The NTSB report on a case where a pilot had been arrested for domestic violence. After being released on bail on 13 August 2018 he had taken Cessna 525 N526CP without permission and flew it into his home in Payson City, UT, killing himself.

Toxicology testing revealed the presence of a medication used to treat depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, some eating disorders, and panic attacks; the pilot did not report the use of this medication to the FAA. The pilot had a known history of depression, anxiety, and anger management issues.

UPDATE 19 May 2020: RAeS webinar: https://youtu.be/pT8uB7fVV44

UPDATE 20 January 2021: Germanwings legacy bringing mental health action for oil and gas pilots

Recent Comments