Psychological Screening of Flight Crew

The circumstances of the recent loss of Germanwings Airbus A320 D-AIPX in the French Alps on 24 March 2015 has thrown attention on how the mental health of pilots and others in safety critical positions is assessed.

Tony Tyler, CEO of the airline trade body International Air Transport Association (IATA), said on Tuesday:

The issue of psychological screening, psychological testing, the evaluation of the mental state of not only pilots but others in the safety value chain as it were, will no doubt be something that has to be considered.… There has been a lot of work done on health care requirements for the crew, but I think people will start looking at these issues now with fresh eyes. We need to draw all the knowledge that we currently have and consider what we need to do about it.

Aviation Safety Network has recently published a list of commercial airline accidents and serious incidents where pilot suicide (intended or actual) is believed to have been a factor. While the probability of such an event remains low, they do have the potential to kill large numbers of people in the air and/or on the ground. The increase in the number of suspected cases involving airliners in the last three years is therefore particularly concerning.

Of the 7,244 fatal aircraft accidents of all types in the United States from 1993 through 2012, 24 (all involving private aircraft) were the result of aircraft-assisted suicide, according to a study published in the journal Aviation, Space and Environmental Medicine in 2014. An earlier 2005 study examined US general aviation accidents between 1983-2003. During that time, 37 pilots either committed or attempted suicide by aircraft with 36 cases resulting in one or more fatality. In that study:

- 100% of the pilots were male and pretty equally balance between those aged <40 and >40

- 38% of the pilots had known psychiatric problems

- 40% of the suicides or attempts were linked to legal troubles

- 46%, were linked to domestic or social problems

- 24% of the cases involved alcohol

- 14% involved illicit drugs

- 24% involved aircraft taken illicitly.

A 1998 study examined UK general aviation accidents between 1970 and 1996:

A review was undertaken of 415 general aviation accidents. Three were definite cases of suicide and in another seven it seemed possible that the deceased had taken their own lives. Therefore, in the United Kingdom, suicide definitely accounts for 0.72% of general aviation accidents and possibly for more than 2.4%. The latter accords more closely with the findings from Germany than from the United States. Previous psychiatric or domestic problems and alcohol misuse are features of these cases. Aerobatics before the final impact is another frequent finding.

A 1993 study in Germany concluded:

Approximately 2-3% of all fatal air accidents may be attributed to suicide, and in many other accidents in aviation there are grounds for inferring that self-destructive or suicidal behaviour was involved. Narcissistic personality traits are of paramount importance for the choice of this suicide method.

The lessons from private flying do not automatically read across to commercial aviation but Alpo Vuorio MD PhD, author of the 2014 study and an aviation specialist in occupational medicine at the Mehiläinen Airport Health Centre in Finland is quoted by Time magazine as saying:

I really wish that we had some kind of deeper thinking about this issue, because it’s one of the most difficult in aviation medicine.

This difficultly is compounded by the main source of data being self-reported and self-reporting mental health problems can lead to a suspension of from flying. “Pilots aren’t going to tell you anything, any more than a medical doctor would about their mental health,” says Scott Shappell, Professor of the Human Factors Department at Embry-Riddle Aeronautics University (ERAU). It is noteworthy that almost all items of Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) guidance for Aviation Medical Examiners (AMEs) on psychiatric conditions require referral to the FAA. Research has shown that self disclosure is affected by fear of stigma and discrimination. European Federation of Psychologists’ Association (EFPA) and the European Association for Aviation Psychology (EAAP) issued a press release on 30 March 2015 stating:

Psychological assessment before entry to flight training and before admission to active service by an airline can help to select pilots who are mentally and emotionally prepared for the work and who can handle stressors effectively. However, it cannot forecast the life events and mental health problems occurring in the life of each individual pilot and the unique way he or she will cope with these.

It has been noted, for example, that:

…nearly one in three Americans meets the criteria for a mental-disorder diagnosis in any year, and more than half of us will qualify at some point in our lives.

Hence, we can anticipate considerable attention on how to identify early warning signs and encourage self-reporting and supportive counselling, without triggering what might be termed organisationally paranoid witch-hunts.

We highly recommend the 2006 book by Bors and Hubbard: Aviation Mental Health: Psychological Implications for Air Transportation

This is not a fundamentally new problem in aviation. On 30 October 1959 DC-3 N55V of Piedmont Airlines crashed at Bucks Elbow Mountain, Virginia, killing 26 of the 27 occupants. Investigators of the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB), forerunner to the NTSB, found the Aircraft Commander had suffered from “serious emotional and mental stress episodes since 1953. He was under psychotherapy at the time of the accident” and ” likely taking Prozine in the period leading up to the accident, an antipsychotic medicine”. The CAB stated that the investigation “demonstrated the need for re-examination of the use of drugs that might affect the capabilities of a flight crew member” and “if a flight crew member’s personal situation demands tranquilizers he should be removed from flying status while on the drugs.”

UPDATE 10 April 2015: Aviation Week and Space Technology has published a balanced editorial: Keep An Open Mind On Pilots’ Mental Health They recall the case of a US pilot who became disturbed and left the cockpit during a flight in 2012, who is now suing his employer for failing to identify his erratic prior behaviour. They however conclude:

However, rather than being defensive about crew mental health issues, as some have been in the wake of the Flight 9525 crash, aviation should be open to the possibility that some changes might be needed. There could be more transparency about what carriers do regarding mental health. Privacy may have to take a backseat to safety to allow the connecting of a pilot’s medical records to the airman’s medical examination process. To be sure, incidents of a pilot’s mental state leading to damage or disruption in flight are exceedingly rare. But aviation has achieved its enviable safety record not by dismissing remote possibilities of failure but by working systematically to eliminate risks wherever it can.

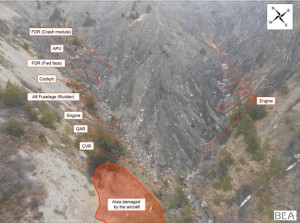

UPDATE 6 May 2015: The BEA issued their preliminary report into this accident. The BEA state they will look at systemic issues of airliner security and:

Medical aspects: the investigation will seek to understand the current balance between medical confidentiality and flight safety. It will specifically aim to explain how and why pilots can be in a cockpit with the intention of causing the loss of the aircraft and its occupants, despite the existence of: ..regulations setting mandatory medical criteria for flight crews, especially in the areas of psychiatry, psychology and behavioural problems; ..recruitment policies, as well as the initial and recurrent training processes within airlines.

UPDATE 18 May 2015: In an article for the BBC Dr Max Henderson, a senior lecturer and consultant psychiatrist at King’s College London, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience, emphasises:

Although the clamour for greater screening for mental illness at work is understandable, in my opinion it is unlikely that screening per se would have prevented the terrible loss of life on board Flight 9525. There are better and more cost-effective ways to reduce the impact of mental illness at work. Greater focus on using our current knowledge to make workplaces healthier, establishing clear confidential pathways for employees to be referred or self-refer if there are concerns about their mental health (such as the Practitioner Health Programme for doctors and dentists), and increasing the proportion of patients able to benefit from both antidepressant medication and talking therapies, all have the potential to improve mental health.

UPDATE 20 June 2015: See more on the FAA’s plans here: FAA Wants More Access to Airman Health Records This article covers the Pilot Fitness Aviation Rulemaking Committee (PFARC), which was formed by a recommendation of the Commercial Aviation Safety Team (CAST) and a market survey for a major update to its aeromedical technology infrastructure called the Aerospace Medicine Safety Information System (AMSIS).

UPDATE 17 July 2015: Today the European Commission published the report it received from a Task Force, led by EASA, created after the Germanwings Flight 9525 accident. The Task Force recommendations are:

- The principle of ‘two persons in the cockpit at all time’ should be maintained.

- Pilots should undergo a psychological evaluation before entering airline service.

- Airlines should run a random drugs and alcohol programme.

- Robust programme for oversight of aeromedical examiners should be established.

- A European aeromedical data repository should be created.

- Pilot support systems should be implemented within airlines.

The Commission say:

Early in its evaluation, the Task Force concluded that improved medical checks on crews could bring a strong contribution to air safety. The evaluation focussed on medical and psychological assessments of pilots, including drugs and alcohol testing, for which screening tests are readily available. The Task Force also pointed at the need for a better oversight framework for aeromedical examiners. The report strives to reach a balance between medical secrecy and safety, and not to create additional red-tape for airlines.

The Commission will review the recommendations, taking into account advice received from other sources such as the independent accident investigation led by the French Civil Aviation Safety Investigation Authority (Bureau d’Enquêtes et d’Analyses (BEA)). Where legislative action is to be taken, EASA will be requested to develop concrete proposals, which will then be included in EU aviation safety regulations. EASA will also be asked to produce non-legislative deliverables such as guidance material and practical tools for information sharing, and to monitor actions taken by Member States and industry.

UPDATE 20 October 2015: The Commission release their action plan. The next steps will be:

- An Aircrew Medical Fitness workshop to be organised in early December 2015. The workshop will gather European and world-wide experts to discuss the implementation of the recommendations. The results of this workshop will be a draft proposal of concrete actions to implement the recommendations, to be further discussed and approved among all the interested parties: European Commission, EASA, airlines, crews, doctors, etc.

- Operational Directives in the area of air operations and aircrew might be published by EASA in the first quarter of 2016 to address specific safety issues and prepare proposals for new rules. Operational Directives are a new regulatory tool which may be used for the first time on this occasion. They will provide operators and national aviation authorities with indications on how to pro-actively implement the recommendations, and what are the actions required.

- New rules such as new acceptable means of compliance (AMC) and guidance material (GM) to existing regulations will be developed as needed before the end of 2016.

UPDATE 9 November 2015: The CHIRP Charitable Trust, who run the UK’s Confidential Human Factors Incident Reporting Programme (CHIRP), has highlighted another problem about stress and self reporting. We discuss it further: CHIRP Critical of an Oil Company’s Commercial Practices

UPDATE 7 December 2015: EASA are staging the two day Aircrew Medical Fitness Workshop, attended by 150 people, that is part of the action plan. Six preliminary concept papers will be further developed based on the workshop’s outcomes in early 2016 and can be expected to be implemented “in the course of 2016”, taking into account any new information from the accident investigation by the BEA.

EASA’s proposals cover the following areas:

- The implementation and strengthening of pilot support and reporting systems within the airlines;

- The mandatory carrying out of psychological evaluation for all pilots before entering service;

- The strengthening of the psychological part of the pilots’ recurrent medical assessment;

- The introduction of drugs and alcohol testing for pilots in the context of their initial medical assessment, as well as within a testing programme by the airline;

- The strengthening of the oversight of aero-medical examiners (who perform the pilots’ medical assessment and issue their medical certificate) and the creation of networks to foster peer support;

- The creation of a European repository of pilots’ aero-medical data, to facilitate the sharing of information between Member States, while respecting patient confidentiality.

UPDATE 8 December 2015: Patrick Ky, EASA Executive Director, said:

This dialogue with all the parties involved is essential to further strengthen the European aviation safety system. We need to act quickly if we want to minimise the risk of a catastrophe such as the Germanwings accident to happen again.

UPDATE 13 March 2016: The BEA issue their final report. Sections 1.16.2 and .3 has a useful discussion on mental health issues and employee assistance programmes. Section 1.16.4 describes studies on anti-depressant medication and flying status. section 1.16.5 looks at how mental health issues are addressed in the French nuclear and rail industries. See our fall analysis: Germanwings: Psychiatry, Suicide and Safety

UPDATE 15 April 2016: The accident report into the deliberate crash of LAM Embraer 190 C9-EMC in Namibia on 29 November 2013 has been issued. All 33 occupants died after the captain, left alone in the cockpit, commanded a rapid descent which culminated in a high-speed collision with terrain.

UPDATE 19 April 2016: Flight International have covered the C9-EMC report. They note the investigators have not made any explicit safety recommendations relating on pilot medical checks in that case. They go on to highlight:

…that the captain had been through a number of difficult personal circumstances including the suicide of his son just nine months earlier.

UPDATE 20 April 2016: EASA have issued the terms of reference for the Rule Making Task (RMT.0700 Aircrew Medical Fitness) on implementation of the recommendations made by the EASA-led Germanwings Task Force. EASA has also organised a public conference 15-16 June 2016 in Cologne to update progress on their actions.

UPDATE 22 April 2016: Concern has been raised Air Transport Association of Canada over the lack of action by Transport Canada: Mental health screening for pilots ‘crack in the armour’ of Canadian airline safety

UPDATE 16 June 2016: The US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has issued a press release on recommendations of an Aviation Rulemaking Committee (ARC) comprised of aviation and medical experts. The FAA say:

In January, the FAA began enhanced training for Aviation Medical Examiners so they can increase their knowledge on mental health and enhance their ability to identify warning signs.

Airlines and unions will expand the use of pilot assistance programs. The FAA will support the development of these programs over the next year. These programs will be incorporated in the airline’s Safety Management Systems for identifying risk.

The FAA will work with airlines over the next year as they develop programs to reduce the stigma around mental health issues by increasing awareness and promoting resources to help resolve mental health problems.

The FAA will issue guidance to airlines to promote best practices about pilot support programs for mental health issues.

The FAA will ask the Aerospace Medical Association to consider addressing the issue of professional reporting responsibilities on a national basis and to present a resolution to the American Medical Association. Reporting requirements currently vary by state and by licensing and specialty boards

However:

The ARC’s experts did not recommend routine psychological testing because there was no convincing evidence that it would improve safety, which the Aerospace Medical Association also concluded…stating that in-depth psychological testing of pilots as part of routine periodic care is neither productive nor cost effective.

Instead, the FAA and the aviation community is embracing a holistic approach that includes education, outreach, training, and encourages reporting and treatment of mental health issues.

UPDATE 17 June 2016: The British Psychological Society (BPS) have a workshop in October 2016 on clinical skills for working with air crew, run by Professor Robert Bor.

UPDATE 28 June 2016: Steve Hull of RTI Forensics, discusses the topic “Do Airlines Really Understand Pilot Suicide?” in an RAeS lecture (available as a podcast).

UPDATE 21 July 2016: EASA has issued a further SIB on Minimum Cockpit Occupancy. EASA say:

CAT.OP.MPA.210 of Regulation (EU) No 965/2012 stipulates that flight crew members required to be on duty in the flight crew compartment shall remain at the assigned station, unless absence is necessary for the performance of duties in connection with the operations or for physiological needs, provided at least one suitably qualified pilot remains at the controls of the aircraft at all times.

In such cases, EASA recommends operators to assess the safety and security risks associated with a flight crew member remaining alone in the flight crew compartment.

EASA say this assessment should consider:

- the operator’s psychological and security screening policy of flight crews;

- employment stability and turnover rate of flight crews;

- access to a support programme, providing psychological support and relief to flight crew when needed; and

- ability of the operator’s management system to mitigate psychological and social risks.

If the assessment leads the operator to require two authorised persons in accordance with CAT.GEN.MPA.135 to be in the flight crew compartment at all times, operators should ensure that:

(a) the role of the authorised person, other than the operating pilot, in the flight crew compartment is clearly defined, considering that his/her main task should be to open the secure door when the flight crew member who left the compartment returns;

(b) only suitably qualified flight crew members are allowed to sit at the controls;

(c) safety and security procedures are established for his/her presence in the flight crew compartment (e.g. operation of the flight deck, specific procedure for entry, use of observer seat and oxygen masks, avoidance of distractions etc.);

(d) training needs are addressed and identified as appropriate;

(e) safety risks stemming from the authorised person leaving the passenger cabin are assessed and mitigated, if necessary; and

(f) resulting procedures are detailed in the Operations Manual and, when relevant, the related security reference documents.

UPDATE 16 August 2016: EASA has published a set of proposals to the European Commission for an update of the rules concerning pilots’ medical fitness:

These rules are contained in so-called Part-MED, which covers aviation safety rules related to the medical aspect and fitness of aircrews.

Released in a document known as an Opinion, these proposals introduce the following new requirements, among others:

- strengthening the initial and recurrent medical examination of pilots, by including drugs and alcohol screening, comprehensive mental health assessment, as well as improved follow-up in case of medical history of psychiatric conditions;

- increasing the quality of aero-medical examinations, by improving the training, oversight and assessment of aero-medical examiners;

- preventing fraud attempts, by requiring aero-medical centres and AMEs to report all incomplete medical assessments to the competent authority.

These proposals have been subject to consultation with all concerned stakeholders. They address relevant safety recommendations made after the Flight 9525 accident by the EASA-led Task Force, as well as by the French “Bureau d’Enquêtes et d’Analyses” (BEA).

The EASA Opinion (Opinion 09/2016) also includes a broader update of Part-MED, aimed at keeping the rules up-to-date with latest developments in the field of medicine and filling any gaps identified through the operational experience.

Next steps: The EASA Opinion will serve as the basis for a legislative proposal by the European Commission towards the end of 2016. To support the implementation of the new rules, EASA has prepared draft guidance material (so-called Acceptable Means of Compliance and Guidance Material – AMC/GM), annexed to the Opinion. The final AMC/GM will be published when the new rules have been adopted by the Commission. A further set of regulatory proposals in the area of Air Operations will follow before the end of the year.

UPDATE 9 December 2016: EASA have issued Opinion 14/2016 ‘Aircrew medical fitness – Implementation of the recommendations made by the EASA-led Germanwings Task Force on the accident of the Germanwings Flight 9525’. This Opinion proposes changes to the Air OPS implementing rules (IRs):

- Preventive measures such as:

- carrying out a psychological assessment of the flight crew before commencing line flying;

- enabling, facilitating and ensuring access to a flight crew support programme; and

- performing systematic drug and alcohol (D&A) testing of flight and cabin crew upon employment.

- Corrective and follow-up measures such as performing flight and cabin crew D&A testing:

- after a serious incident;

- after an accident;

- following a reasonable suspicion; and

- unannounced after rehabilitation and return to work.

- A complementary measure: mandatory random alcohol screening of flight and cabin crew within the ramp inspection programme to ensure an additional safety barrier.

UPDATE 15 December 2016: A study by the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health shows hundreds of pilots are suffering from depression.

UPDATE 2 March 2017: Mental health: IoD calls for ‘a little more conversation’ (click here to download a PDF of the IoD report).

UPDATE 17 March 2017: Jobs with highest risk of suicide for men and women revealed

UPDATE 18 March 2017: Discussing mental health issues from a military pilot perspective: When Good Pilots Go Bad

Meanwhile for practical information on on Setting Up and Running a Pilot Support programme, Core Aviation Psychology will be holding a workshop on Wednesday 12 April 2017 from 10.00 to 16.00 at the Crowne Plaza Hotel, Aberdeen Airport.

UPDATE 7 December 2017: Aviation Personnel Mental Health and Wellbeing: Commissioned by the Professional Practice Board of the British Psychological Society in 2016, a group of expert aviation psychologists chaired by Professor Robert Bor developed a Position Paper on Aviation Psychology, with focus on the mental health and wellbeing of pilots and other aviation personnel.

UPDATE 26 May 2018: Pilot mental health care still facing ‘normalisation’ barriers said speakers at an RAeS conference on aircrew mental health, held in London on 24 May 2018.

UPDATE 30 September 2018: CAP1695: Pilot Support Programme – Guidance for Commercial Air Transport (CAT) Operators from UKCAA.

UPDATE 28 January 2019: Commander of Crashed Dash 8 Q400 in Nepal “Harboured Severe Mental Stress” Say Investigators

UPDATE 30 January 2019: There will be an RAeS conference on Aerospace Mental Health and Wellbeing 22-23 May 2019 in London.

UPDATE 24 March 2019: Unconfirmed press report: Allegedly suicidal pilot crashes into Botwana clubhouse in attempt to kill wife and friends (KA200 A2-MBM).

UPDATE 3 January 2020: Caring for Pilots (RAeS 2019 conference summary)

Aerossurance is pleased to be sponsoring the Chartered Institute of Ergonomics & Human Factors‘ Human Factors in Aviation Safety conference at East Midlands Airport 9-10 November 2015.

Recent Comments