Rockets Sleds, Steamships and Human Factors: Murphy’s Law or Holt’s Law?

Murphy’s Law: Whatever can go wrong, will go wrong. To some a pessimistic inevitability, to others a call to arms for defensive design to prevent opportunities for failure. We look at how that ‘law’ was named and how the origins of the ‘law’ actually stretch back to a Liverpool ship-owner and engineer in 1877.

That Man Murphy

‘Murphy’s Law’ was not reference to a generic accident prone Irishman as some believe, but to Major Edward Aloysius Murphy Jr. USAF (b 11 Jan 1918 d 17 Jul 1990).

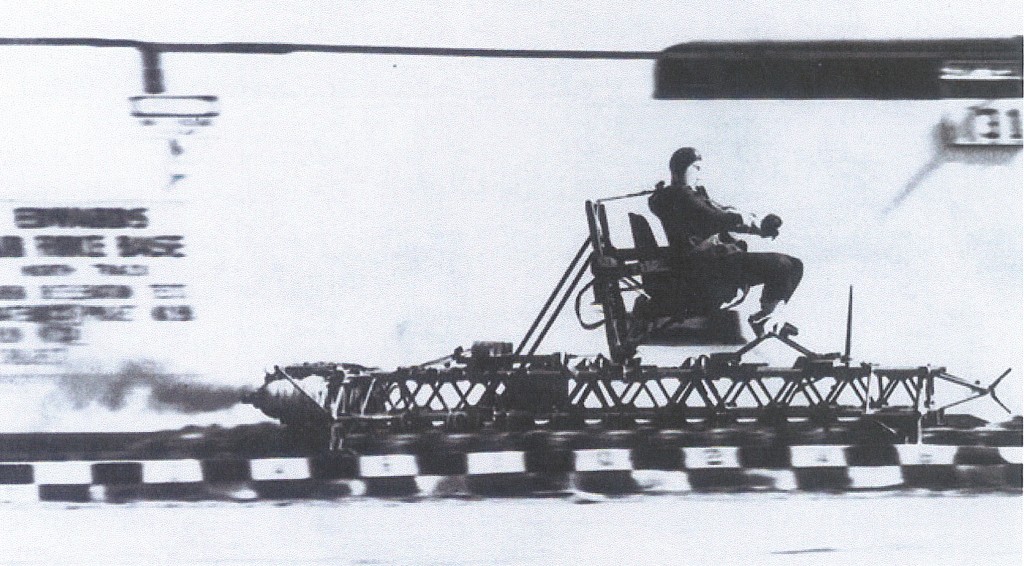

As described Nick Spark, author of A History of Murphy’s Law, Murphy was a USAF engineer working on instrumentation for an aerospace medical research programme, MX981. The programme used high-speed rocket sleds at Muroc Army Air Field (later renamed Edwards Air Force Base) to examine human tolerance to acceleration and deceleration.

The human in question was frequently researcher Colonel John Paul Stapp, MD PhD (b 11 Jul 1910 d 13 Nov 1999). Stapp’s work using the rocket sled had a profound influence in the field of crashworthiness, human survivability and motor vehicle safety. However, it was hazardous work that on a good day left the subject with black eyes (from their eye-balls ‘punching’ their eye-lids) and sometimes worse (Stapp broke several bones), with the greatest deceleration experience by Stapp being 46.2g.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_detailpage&v=s4tuvOer_GI

Murphy had designed a strain-gauge device to more accurately measure the deceleration. When it was first tested, there was massive disappointment as it had not recorded data. When examined it was discovered that it had been mis-wired and in particular there were two ways to wire the unit (only one of which would result in success). Although who said what remains disputed, according to Stapp, at a subsequent press conference on the trials, that was where ‘Murphy’s Law’ was born.

https://youtu.be/SRZ4deJsndM

Error tolerance of designs had already been recognised in the early days of civil aviation though. In 1925 Major General Sir Sefton Brancker, the UK’s Director of Civil Aviation has said in a presentation to the Royal Aeronautical Society (discussed in Flight):

Error of judgement had been the basic cause of 8 out of 12 dangerous accidents. These could be divided into categories, five of which were the fault of the pilot in that he took the wrong action, and three of which were caused by failure to handle the aircraft correctly. The second category did affect the designer. From the beginning the designer had always been prone to assume that his aircraft would be flown by an absolutely first-class pilot. In air transport we want a really foolproof machine…

Perhaps ironically Brancker perished in the R101 airship disaster in 1930.

However, it appears that the concept named at a Californian dry lake actually has nautical origins…

Alfred Holt

Liverpool ship-owner and engineer Alfred Holt had formed the Alfred Holt and Company on 11 January 1865. Its main operating subsidiary was the Ocean Steam Ship Company, trading as Blue Funnel Line.

Holt, an accomplished marine engineer, formed the company at the height of the great sail-powered clipper ships, to exploit developments in steamship technology.

It has been said that Holt “had no romantic feelings for the clippers…and had an unshakeable belief in steam propulsion”. Francis Hyde in his 1957 book Blue Funnel, quotes Holt that “the main problems…centred around the screw propeller, the building of a ship in iron, and the compound engine”. Holt was among the first to combine the three features successfully. The subsequent opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 was key to the rapid growth of the company, that primarily focuses on Far East trade.

Alfred Holt by Robert Edward Morrison

Alfred was not only a gifted technician but a man of restless energy, great intellectual curiosity with considerable powers of leadership. He has recorded a good deal about himself and was evidently possessed with a remarkable personality. He was also clearly a good man, who, for all his pugnacity and quick temper, dealt in justice and kindliness.

‘Holt’s Law’ and His Observations on Design Human Factors

In 1877 Alfred Holt said in a paper presented to the Institution of Civil Engineers (for which he was awarded the Institution’s James Watt Medal and a Telford Premium):

It is found that anything that can go wrong at sea generally does go wrong sooner or later.

Source: Holt, A. (1878). Review of the Progress of Steam Shipping during the last Quarter of a Century, Minutes of Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers, Vol. LI, Session 1877–78—Part I. (November 13, 1877 session, published 1878).

In the same paper he also sets out other key design principles and interestingly referring the ‘the human factor’ as a design consideration:

Sufficient stress can hardly be laid on the advantages of simplicity.

The human factor cannot be safely neglected in planning machinery.

It is almost as bad to have too many parts as too few.

These philosophies may stem from the fact that as soon Alfred Holt & Co was launched, the company had focused on ensuring a reliable and punctual service (something the clipper ships could not). Additionally, from 1874 onwards Alfred Holt & Co had also adopted a policy of self-insurance, which necessitated higher standards of construction, maintenance and personnel than the industry norm, meticulous voyage planning and building up the company’s financial reserves.

Holt on Regulation

In a foretaste of current discussions on the benefits of performance based regulation over prescriptive regulation, in the same ICE paper, Holt also touched on the issue of increasingly overly-prescriptive regulation by the Board of Trade, “emotional legislation” and “the eccentricity of the laws”. The “emotional legislation” comments related to the Merchant Shipping Acts of 1875-1876, backed by Samuel Plimsoll MP. Holt, according to Francis Hyde, objected to these acts and Plimsoll’s “political humbug”, because “they were content with a lower margin of safety than he had ever sanctioned in his own [self-insured] ships”.

In his paper Holt sated that:

The system [of regulation] was too new to have wrought much ill yet; but resistance to novelties and preference for stereotyped forms might naturally be expected.

One factor in the loss of life on the RMS Titanic in 1912 was that Board of Trade prescriptive regulations for lifeboat capacity had not kept pace with modern ship design despite public and parliamentary debate on the matter. Perhaps this is an example of the ‘eccentricity’ Holt observed and the ‘ill’ he warned of.

Final Word

In discussion, spread over 4 evenings, after his paper (chaired by GR Stephenson) Holt said:

…he could at least claim for his Paper the merit of having provoked a very interesting discussion.

We hope it still does today.

Acknowledgement: Thanks to the ICE Library for their assistance in researching this article.

Aerossurance is pleased to be supporting the annual Chartered Institute of Ergonomics & Human Factors’ (CIEHF) Human Factors in Aviation Safety Conference for the third year running. We will be presenting for the second year running too. This year the conference takes place 13 to 14 November 2017 at the Hilton London Gatwick Airport, UK with the theme: How do we improve human performance in today’s aviation business?

UPDATE 24 October 2022: The Royal Aeronautical Society (RAeS) has launched the Development of a Strategy to Enhance Human-Centred Design for Maintenance. Aerossurance‘s Andy Evans is pleased to have had the chance to participate in this initiative.

Recent Comments