Visual Illusions, a Non Standard Approach and Cockpit Gradient: Business Jet Accident at Aarhus (Aerowest C560XLS+ D-CAWM)

On 5 August 2019 business jet Cessna 560 XLS+ D-CAWM of Aerowest. inbound from Oslo, was destroyed landing at Aarhus (EKAH).

The 3 crew and 7 passengers were able to evacuate without injury.

The Accident Flight

The Accident Investigation Board Denmark (AIBD) explain in their safety investigation report (issued 10 June 2020) that:

The commander was the pilot flying, and the first officer was the pilot monitoring. The commander was an experienced pilot and highly ranked at the operator. [This was the] first officer’s first job as a commercial pilot. As a consequence of the [first officer’s] latest OPC [Operator Proficiency Check] grading, the Head of Training & Standards restricted the first officer to fly only with supervision commanders. An on-board cabin crewmember was not a formal requirement for this aircraft type. The cabin crewmember had not received specific aircraft type training (not required) and was not formally responsible for on-board cabin flight safety

The accident occurred in dark night under Instrument Meteorological Conditions (IMC). The forecasted weather conditions at EKAH were generally consistent with the actual weather reports…. Fog could be expected and was present at EKAH. However, on initial radio contact with Aarhus Tower, the first officer perceived, noted, and read back to the commander the meteorological visibility to be 2500 m instead of the reported 250 m.

AIBD suggest this may have created a false perception that the visibility was better than it actually was. Aarhus Tower had also stated that…

Runway Visual Range (RVR) at landing to be 900 m, 750 m, and 400 m in fog patches.

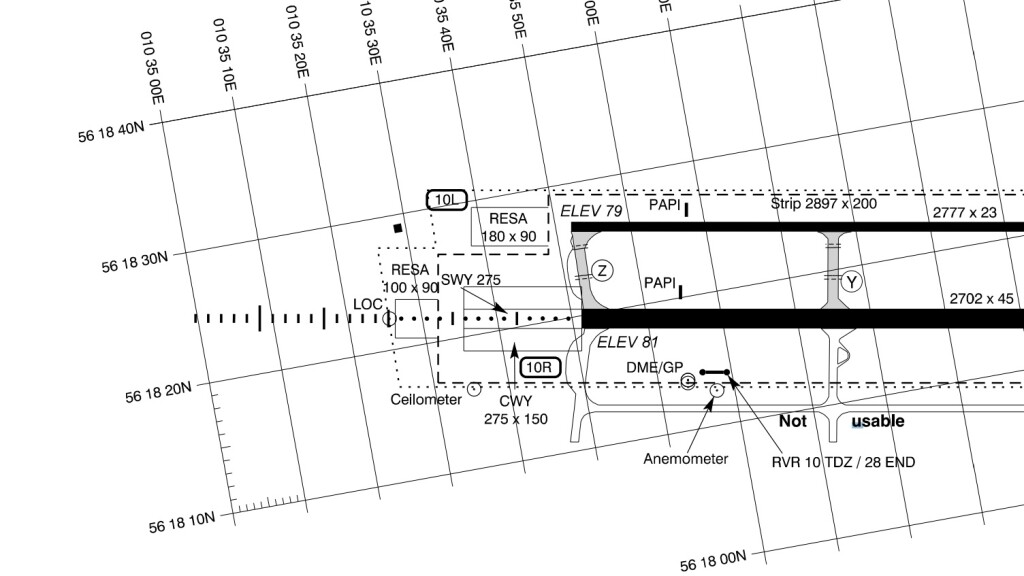

The commander made an approach briefing for the Instrument Landing System (ILS) for runway 10R including a summary of SOP in case of a missed approach. The flight crew performed the approach checklist [and] discussed the weather situation at EKAH with expected shallow fog and fog patches at landing. The commander informed the first officer that the intention was to touch down at the beginning of the runway.

In order to avoid entering fog patches during the landing roll, the commander planned flying one dot below the GS [Glide Slope], performing a towed approach, and touching down on the threshold. However, the commander did not communicate this plan of action to the first officer. The aircraft started descending below the GS for runway 10R.

The first officer asked the commander whether to cancel potential Enhanced Ground Proximity Warning System (EGPWS) GS warnings. The commander confirmed. The aircraft aural alert warning system announced passing 500 feet RH. The recorded computed airspeed was 125 kt, the recorded vertical speed was approximately 700 ft/minute, and the GS deviation approached one dot below the GS. The commander noted the PAPI indicating the aircraft flying below the GS (one white and three red lights). The first officer called “Approaching minimum”. Shortly after, the aircraft aural alert warning system announced “Minimums Minimums”. The FDR recorded a beginning thrust reduction towards flight idle and a full scale GS deviation (flying below).

The commander called “Continue”. The commander had visual contact with the approach and runway lighting system. It was the perception of the first officer that the commander had sufficient visual cues to continue the approach and landing. The first officer as pilot monitoring neither made callouts on altitude nor deviation from GS. The commander noticed passing a white crossbar, a second white crossbar and then red lights. To the commander, the red lights indicated the beginning of runway 10R, and the commander initiated the flare.

The aircraft collided with the antenna mast system of the localizer (LLZ) of runway 28L located 450 meters before the beginning of runway 10R.

The left wing fuel tank was ruptured and fuel started to leak.

The aircraft touched down in the Runway End Safety Area (RESA) for runway 28L. After a landing roll of approximately 60 meters, the nose landing gear collided with the near field antenna of the LLZ for runway 28L and collapsed.

While rolling on the main wheels and skidding on the nose section, the aircraft entered the stopway for runway 28L and came to a full stop on runway 10R…approximately 230 m after the beginning of runway 10R…

Upon full stop on runway 10R, the first officer with a calm voice reported to Aarhus Approach “Aarhus Tower, Delta Whiskey Mike, we had a crash landing”. The cabin crewmember…initiated the evacuation of the passengers via the cabin entry door.

Leaking fuel from the left wing fuel tank caught fire, and the fire eventually engulfed the left side of the aircraft fuselage.

AIBD Analysis

Although, the commander’s plan of action “might have been unclear”, the AIBD note “the flight crew accepted and instituted a deactivation of a safety barrier by cancelling potential EGPWS GS alerts”. They also note they deviated from SOP “by not maintaining the GS upon runway visual references in sight”. AIBD consider this compromised safety of the flight.

The first officer as pilot monitoring believed that the commander by calling Continue had appropriate visual cues to complete the approach and landing and made no corrective callouts on altitude, GS deviation or unstabilized approach.

The AIB believes that the commander, from passing the set ILS approach minima until touchdown, mostly relied on external visual cues and potential corrective call-outs from the first officer. The first officer mentally seemed to rely on the commander’s perception of external visual cues and did not challenge, though expected to partly monitor the flights instruments, a full scale GS deviation (more than two dots below the GS).

In the opinion of the AIB, the first officer, in a critical stage of the flight, did not provide effective monitoring and operational support to the commander and did not recognize the unstable approach.

The flight crew seemed to be unaware of the developing unsafe condition and probably was, due to lack of situational awareness and vigilance, unable to recognize the need for corrections.

To the commander, target fixation on touching down on the threshold might have provoked a steeper than intended short final approach leaving out alternate options like aborting the approach.

AIBD discuss the issue of cockpit gradient:

The AIB finds it possible that the commander’s rank and experience at the operator biased the first officer on final approach to allow concentration of authority/power in one person steepening the flight crew gradient.

AIB questions the effect of an imposed restriction [on the first officer after the OPC] rather than additional pilot training.

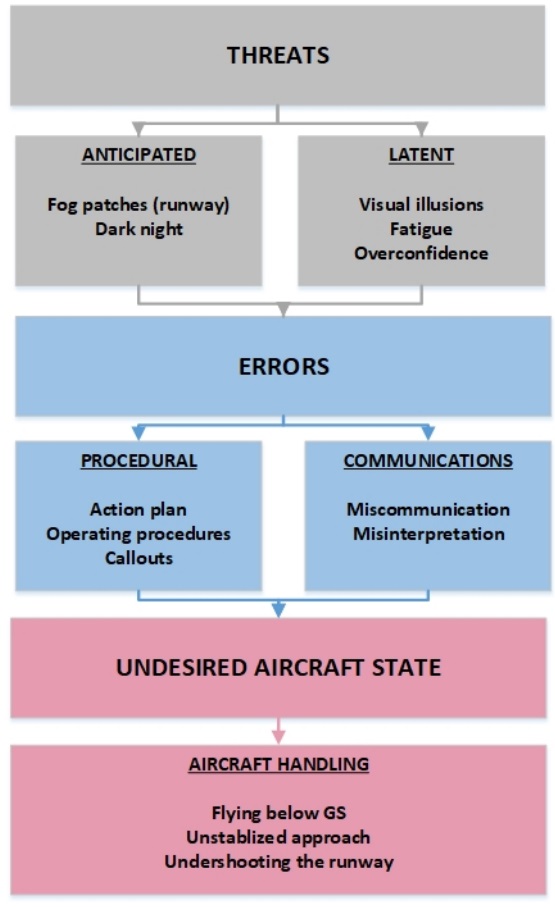

AIBD present this Threat and Error Management (TEM) summary for the accident:

The commander mitigated a perceived threat (concern about entering fog patches during the landing roll) by an action plan on going one dot below the GS, performing a towed approach, and touching down on the threshold and thereby introducing and facing other operational threats. It seems unlikely that the flight crew was aware of the potential consequences of these introduced threats.

Factors identified by AIBD that could have created a visual illusion of the aircraft being high include:

- Dark night.

- Bright approach and runway lighting.

- Limited runway visibility.

- Fog patches above the middle of the runway. –

- Concern about entering fog patches during the landing roll.

The visual illusion might have provoked a steeper than intended short final approach and target fixation on touching down on the threshold leaving out alternate options like aborting the approach. Furthermore, a visual illusion of being overhead the stopway for runway 28L at passage of the two red omnidirectional aerodrome fence obstacle lights most likely changed the commander’s perception of flight progress from initiating a towed approach to a flare resulting in the collision with the antenna mast system of the LLZ of runway 28L. Generally seen, the flight crew did not employ appropriate execution countermeasures to keep threats, errors, and an undesired aircraft state from reducing margins of flight safety.

AIBD Conclusions

AIBD identified the following causal factors:

- An action plan on flying below the Glide Slope (GS), performing a towed approach, and touching down on the threshold in dark night and low visibility.

- A deactivation of a hardware safety barrier.

- Deviations from Standard Operating Procedures (SOP).

- Less than optimum Crew Resource Management (CRM).

- A confusion over and a misinterpretation of the Category (CAT) 1 approach and runway lighting system of runway 10R.

Safety Resources

- Flight Safety Foundation ALAR Toolkit and especially FSF ALAR Briefing Note 5.3 — Visual Illusions and FSF ALAR Briefing Note 2.2 — Crew Resource Management

- Night Visual Approaches

- Night flight illusions – explained

Past Aerossurance articles include:

- Fatal US G-IV Runway Excursion Accident in France – Lessons

- Execuflight Hawker 700 N237WR Akron Accident: Casual Compliance

- Unstabilised Approach Accident at Aspen

- Business Jet Collides With ‘Uncharted’ Obstacle During Go-Around

- G200 Leaves Runway in Abuja Due to “Improper” Handling

- Cockpit Tensions and an Automated CFIT Accident

- Disorientated Dive into Lake Erie

- Global 6000 Crosswind Landing Accident – UK AAIB Report

- Fatal Flaws in Canadian Medevac Service

- ‘Procedural Drift’: Lynx CFIT in Afghanistan

- HEMS Black Hole Accident: “Organisational, Regulatory and Oversight Deficiencies”

- UPDATE 8 July 2020: Challenger Damaged in Wind Shear Heavy Landing and Runway Excursion

- UPDATE 9 December 2020: A Saab 2000 Descended 900 ft Too Low on Approach to Billund

- UPDATE 20 May 2023: Oil & Gas Aerial Survey Aircraft Collided with Communications Tower

Recent Comments