So You Think The Gulf of Mexico (GOM) is Non-Hostile?

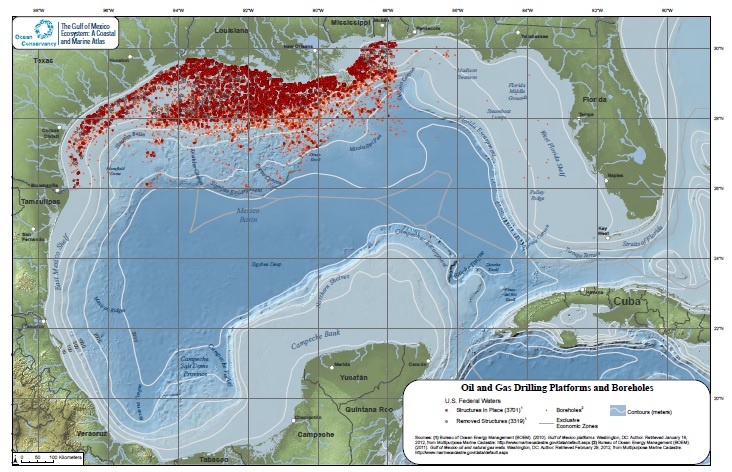

The Gulf of Mexico (GOM), off the coast of Mississippi, Louisiana and Texas in particular, remains a busy area for offshore helicopter operations with over 2 million passengers carried and nearly 300,000 flying hours last year (see our article: Helicopter Ops and Safety – Gulf Of Mexico 2014).

It is a sea area generally thought as non-hostile, i.e. where:

- A safe forced landing can be accomplished [i.e. a controllable aircraft can make a ditching and escape is possible]; and

- The helicopter occupants can be protected from the elements; and

- Search and rescue response/capability is provided consistent with the anticipated exposure;

Indeed for the vast majority of the time the GOM does meet the definition of non-hostile. But very occasionally not…

While most observers would expect operations in the immediate vicinity of seasonal hurricanes to affect survivability, winter can do too, particularly if survivors are not able to board a life raft and Search and Rescue (SAR) is not prompt, as demonstrated by the US National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) report on the loss a Bell 206L4, N180AL, owned and operated by Rotorcraft Leasing Company (RLC) on 11 December 2008.

The Accident

The pilot and four passengers on-board died after the helicopter impacted the sea approximately 8 minutes after departing Sabine Pass, Texas en route to a platform in the West Cameron 157 block of the GOM. According to the NTSB:

The wreckage was located 2 miles offshore in 13 to 15 feet of water, along the helicopter’s route of flight. Damage was consistent with controlled flight into the water.

Wreckage of Rotorcraft Leasing Company (RLC) B206L4 N180AL (Credit: NTSB) Note: Decals over the name of the former owner have come loose after the exposure to sea water.

The fuselage was broken into three pieces and the skids (on which were mounted floats and external liferafts) were broken off, suggesting a relatively high speed impact, not a controlled ditching.

They go on to say:

A cold front had just passed through the area several hours prior to the accident.

The Aviation Weather Center…0500… forecast for coastal waters, including the accident helicopter’s route of flight, predicted scattered to broken clouds at 1,000 feet, broken clouds at 2,500 feet, with clouds tops at 5,000 feet. The surface winds were forecast to be out of the northwest at 20 to 25 knots. Occasional broken clouds at 700 feet with visibility three to five miles in rain and mist were forecast.

The National Weather Service also had a full series of Airman’s Meteorological Information (AIRMET) current for the area. AIRMET Zulu for moderate icing conditions from the freezing level to 20,000 feet, AIRMET Tango for potential moderate turbulence below 12,000 feet, and AIRMET Sierra for instrument flight rules conditions with ceilings below 1,000 feet and/or visibility below three statute miles in precipitation and mist.

The air temperature was recorded at 34 degrees Fahrenheit [1 degree Centigrade] and the water temperature was recorded at 64 degrees Fahrenheit [17 degrees Centigrade].

The pilot held a commercial certificate and an instrument rating; however, he was not approved for instrument flight under Part 135 and was not current.

There was no record to indicate that the pilot had obtained a formal weather briefing from a recorded source.

According to RLC, other flights in the area had been grounded or delayed due to the passing weather.

The NSTB concluded the probable cause of the Controlled Flight into the Terrain (CFIT) was (rather unhelpfully):

The pilot’s failure to maintain clearance from the water.

They go on:

Contributing to the accident was the inadvertent encounter with instrument meteorological conditions.

This accident does highlight important survival and alerting / flight following issues and resulted on Jacob’s Law in Louisiana.

Survival

While the fuselage damage indicates a significant water impact, autopsy results suggest that at very least the passengers could potentially have survived if suitable equipped. In the case of a Cougar Sikorsky S-92A off Newfoundland, Canada on 12 March 2009 in which 17 people died, one passenger, Robert Decker, survived a seemingly far more destructive impact.

The NTSB state :

The pilot, whose personal flotation device was inflated and secured, suffered severe chest injuries complicated by asphyxia due to drowning.

Two passengers were secured within their flotation devices; however, neither flotation device had been inflated. Two passengers were not wearing flotation devices when they were located; however, two personal flotation devices from the accident flight were recovered and showed signatures consistent with use. One had been partially inflated, and the second had been entirely inflated.

The 4 passengers suffered asphyxia due to drowning with probable complication of cold water shock and hypothermia.

Although a sea temperature of 17 degrees C is higher than in many regions where survival suits are used, it is the combination of temperature and time to rescue (among other factors) that are critical. In this case, if survival suits were being worn, the chances of survival would have been substantially higher.

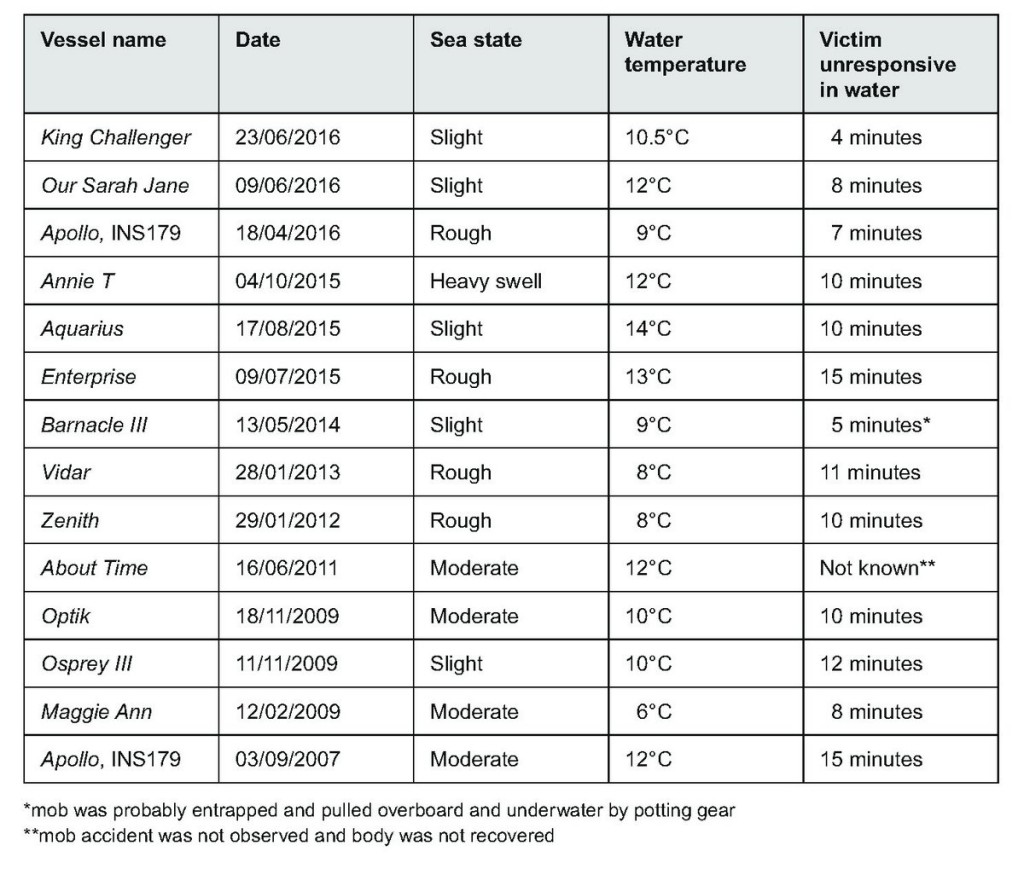

UPDATE 3 November 2016: The UK Marine Accident Investigation Branch (MAIB) report into a man over board fatality from the Fishing Vessel Apollo contains a table that shows how quickly outcomes can turn fatal for individuals without survival suits in cold water only factionally cooler:

Alerting

The Emergency Locator Transmitter (ELT) did not appear to have activated.

The aircraft was fitted with a SkyConnect satellite tracking system, but it appears that familiarity with a different system on other aircraft in the operator’s fleet and an inadequate checklist may have influenced a failure to activate it:

The SkyConnect toggle switch had a selection position of on or off. According to company records, the pilot had been flying the accident helicopter for two or three days prior to the accident. During this time there was no track record for the helicopter. This is consistent with the pilot not activating the SkyConnect system.

The pilot normally flew a helicopter in which the flight tacking system engaged when the master switch was turned on. The accident helicopter required the SkyConnect system to be activated by a separate switch in the cockpit. This variation was not in the checklist. Following the accident the company issued a Safety Alert to all of their pilots to rectify this situation.

The lack of satellite tracing meant flight following would purely be by radio calls every 15 minutes to the operator’s Communications Centre. It is not clear if the checklist was changed after the accident or if the Communications Centre flight following team were then be tasked with notifying pilots when they were not receiving satellite data.

According to the NTSB:

At 0725, the pilot contacted RLC Communications Center and filed a flight plan…. The pilot reported that he…expected to arrive at the destination at 0742.

When the 15 minutes had elapsed (from the time the pilot filed his flight plan until his anticipated position report was due) the dispatcher immediately began to look for the helicopter. She attempted to contact the pilot at the destination platform, and the departure location with no success.

The dispatch supervisor was notified of the missing helicopter within eight to 13 minutes of the missed report. Company helicopters in the area were launched in search of the missing helicopter with negative results.

According to the Coast Guard they were notified of the missing helicopter at 0917.

Recovery vehicles were dispatched, and the helicopter wreckage was located approximately 1100 and recovered to Broussard, Louisiana, for further examination.

Assuming that on this short flight a radio call was expected at the scheduled arrival time 0742, 1 hour 35 minutes elapsed before the US Coast Guard (USCG) report they were informed.

The wreckage was then located within in 1 hour 43 minutes of the USCG being notified (3 hours 18 minutes after the scheduled time of arrival and 3 hours 30 minutes after the NTSB’s estimated impact time).

The NTSB state:

The investigation was unable determine if the company’s delay in notifying the Coast Guard contributed to the severity of injuries in the accident.

Previous Accident

The circumstances are particularly tragic as another GOM operator had a fatal accident in December 2007 with similar survivability and rescue aspects. This highlights the value of collaborative industry safety information exchange and learning from other people’s accidents in advance of the publication of official accident reports.

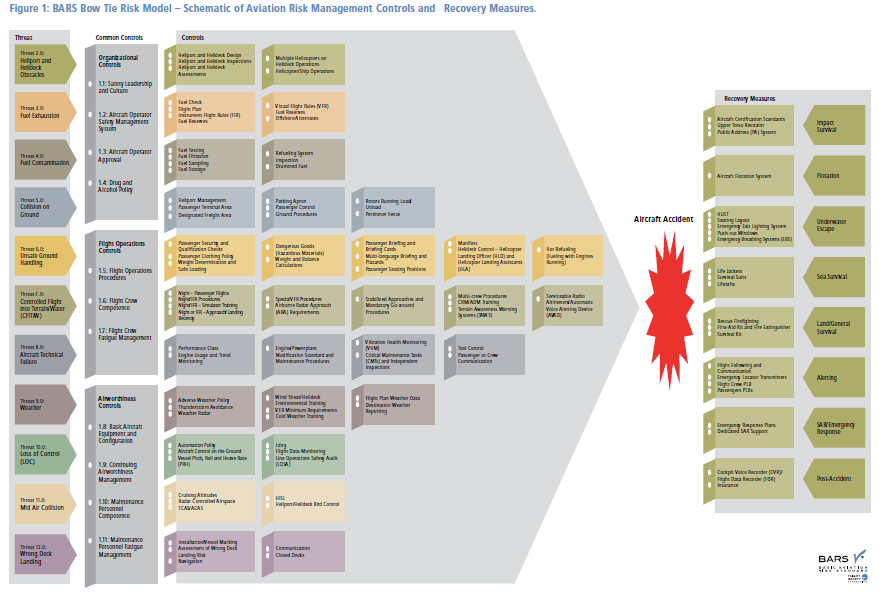

Offshore Helicopter Operations Safety Resource: FSF BARSOHO

To better understand the recovery measures of an offshore helicopter accident we recommend the Flight Safety Foundation (FSF) Basic Aviation Risk Standard for Offshore Helicopter Operations (BARSOHO), launched in May 2015. It is based on their of their award winning Basic Aviation Risk Standard, used in the mining industry, but tailored to offshore operations.

The standard is orientated around a risk bow-tie, contains a number of common and specific threat controls as well as recovery measures (grouped in distinct categories, for survival after an offshore accident):

The whole BARSOHO standard is freely available, with an accompanying implementation guide.

In the case of N180AL the controls and defences that would have been particularly relevant include:

- Common Control 1.1: Safety Leadership and Culture

- Common Control 1.2: Aircraft Operator Safety Management System

- Common Control 1.5: Flight Operations Procedures

- Common Control 1.6: Flight Crew Competence

- Control 6.1: Passenger Security and Qualification Checks

- Control 6.2: Passenger Clothing Policy

- Control 6.6: Passenger Briefing and Safety Cards

- Control 7.9: CRM/ADM Training

- Control 7.11: Serviceable Radio Altimeters / Automatic Voice Alerting Device (AVAD)

- Control 9.1: Adverse Weather Policy – this is a highly relevant item (with 20.20)

- Control 9.5: VFR Minimum Requirements

- Control 9.7: Flight Plan Weather Data

- Control 10.4: Icing

- Defence 20.1: Aircraft Certification Standards (Impact Survival)

- Defence 20.2: Upper Torso Restraint (Impact Survival)

- Defence 20.4: Aircraft Flotation System (Flotation)

- Defence 20.5: Helicopter Underwater Escape Training (HUET) (Underwater Escape)

- Defence 20.6: Seating Layout (Underwater Escape)

- Defence 20.7: Emergency Exit Lighting System (Underwater Escape)

- Defence 20.8: Push-out Windows (Underwater Escape)

- Defence 20.9: Emergency Breathing Systems (EBS) (Underwater Escape) – if the area was identified as hostile

- Defence 20.10: Life Jackets (Sea Survival)

- Defence 20.11: Survival Suits (Sea Survival) – if the area was identified as hostile

- Defence 20.12: Liferafts (Sea Survival)

- Defence 20.16: Flight Following and Communication (Alerting)

- Defence 20.17: Emergency Locator Transmitters (Alerting)

- Defence 20.18: Flight Crew PLB (Alerting) – if the area was identified as hostile

- Defence 20.19: Passenger PLBs (Alerting) – if the area was identified as hostile

- Defence 20.20: Emergency Response Plans (SAR / Emergency Response) – this is a highly relevant item (with 9.1)

- Defence 20.21: Dedicated SAR Support (SAR / Emergency Response) – if the area was identified as hostile and other SAR cover insufficient

- Defence 20.22: Cockpit Voice Recorder (CVR) / Flight Data Recorder (FDR) (Post-Accident)

- Defence 20.23: Insurance (Post-Accident)

UPDATE 1 February 2017: BARSOHO Version 3, fully aligned with the HeliOffshore Safety Performance Model, resulting in some re-ordering of content, is now issued and available.

UPDATE 11 December 2017: The NTSB issue the probable cause on a fatal accident involving Bell 206B N978RH of Republic Helicopters off the coast of Galveston Island, TX on 6 February 2017 that again highlights GOM survivability.

UPDATE 7 June 2023: Jacob’s Law was signed into law after a campaign by Jacob Matt’s parents after the December 2008 accident to N180AL.

Extra Resources

If you found this article of interest you may also enjoy:

- The Hon Robert Wells QC’s Offshore Helicopter Safety Inquiry (OSHSI) following an S-92A accident offshore Canada in 2009, in which 17 people died and one passenger, Robert Decker, survived.

- Helicopter Ditching – EASA Rule Making Team RMT.0120 Update on a new rule making initiative in Europe that will shortly proceed to a Notice of Propose Rulemaking

- New Helicopter Survival Suits in Canada for oil and gas flights off the Atlantic coast of Canada

- Norwegian Survival Suits: Suited for Safety

- Rapid Progress with a Category A EBS in the UK following CAP1145

- OPITO Compressed Air Emergency Breathing System (CA-EBS) Initial Deployment Training Standard

UPDATE 17 December 2015: See also our report: Canadian Coast Guard Helicopter Accident: CFIT, Survivability and More

Recent Comments