Safety Data Silo Danger – Data Analytics Opportunity

We recently enjoyed reading The Silo Effect by Gillian Tett. Tett, who has a PhD in social anthropology, is a journalist and senior editor for the Financial Times. Some organisations are, often by design, divided into silos (by project or by functional specialism). Silos however can restrict who we talk to and how we share information. Such ‘structural secrecy’ was noted by sociologist Prof Diane Vaughan in her examination of the disastrous NASA Space Shuttle Challenger launch decision.

Tett (who discusses her work in this podcast) argues that the observational discipline of anthropology can also identify the unspoken silos within a organisation (as well as society as a whole). From a safety perspective the most interesting case study comes in the book’s introduction, a case study that is less about anthropological observations and more about data collation and analysis.

Fighting Fire with Data

On 25 April 2011 a fire a 2321 Prospect Avenue in the Bronx claimed three lives. The property had been “illegally subdivided, leading city officials to pledge a crackdown on a practice that can impede fire-fighters and imperil lives” in the resulting furore.

New York City had a team of building inspectors and they were not short of complaints to investigate. Each year they received 20,000 complaints on the nearly 1 million buildings and 4 million properties in their remit via the city’s 311 phone line (which receives 30,000 calls on a host of topics every day). However, only 13% of those complaints when investigated wre valid, wasting time and limited resources. Another city department, the fiercely independent New York Fire Department (NYFD) had overlapping duties and its own data, effectively an inaccessible silo, but key data turned out to be split between many city departments and databases.

In May 2011 New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg appointed Mike Flowers to head a new Mayor’s Office of Data Analytics (MODA) and create what some have called ‘The Mayor’s Geek Squad’ of data analysts. They started to develop a way to use data from multiple sources (not just Dept of Buildings and NYFD data) to prioritise attention on the most probable reports of illegal conversions. Flowers said:

Before we started, we didn’t know what we knew.

The analysts did more than look at data. They spent time with building inspectors and fire-fighters to understand more about illegal conversions and fires. Flower’s explains that what they then did was:

…come up with a way to prioritize those [complaints] which represent the greatest catastrophic risk… In doing that, we built a basic flat file of all 900,000 structures in the city of New York and populated them with data from about 19 agencies, ranging from whether or not an owner was in arrears on property taxes, if a property was in foreclosure, the age of the structure, et cetera. Then, we cross-tabulated that with about five years of historical fire data of all of the properties that had structural fires in the city, ranging in severity.

After we had some findings and saw certain things pop as being highly correlative to a fire, we went back to the inspectors at the individual agencies, the Department of Buildings, and the fire department, and just asked their people on the ground, “Are these the kinds of conditions that you see when you go in post-hoc, after this catastrophic event? Is this the kind of place that has a high number of rat complaints? Is the property in serious disrepair before you go in?” And the answer was “yes.” That told us we were going down the right road.

The success rate with the new Risk Based Inspection System increased five fold from 13% to over 70%.

While the aim was to reduce the number of deaths through fires and structural collapses, the reality is that these are relatively rare so MODA also had to think about the leading indicators of outcomes. Flowers says:

When we increase the speed of finding the worst of the worst by prioritizing the complaint list, we are reducing our time to respond to the most dangerous places, and we are in effect reducing the number of days that residents are living at risk. We calculated that as a reduction in fire-risk days.

More philosophically, Flowers goes on:

There is an important distinction between collecting and connecting data. Data collection is based upon the actual operation of services in the field… It’s our job to work with the data that is currently collected. Instead of constantly pushing for new data, we rely upon what is already being collected and consult the agencies over time as they change and modernize their practices.

The greatest challenge for the analytics team is moving from insight to action. Insight is powerful, but it’s worthless if the behavior in the field doesn’t change. … we make sure that [new] information is being delivered right alongside currently reported data, not in a different, detached method. It sounds simple, but it’s so easy to go wrong. Don’t change the front line process; change the outcome.

Flowers says the lessons from MODA are: You don’t need:

- a lot of specialised personnel

- a lot of high-end technology.

- ‘perfect’ data but you do need all the dataset

You must:

- talk with the people behind the data, see what they see and experience what they experience

- focus on generating actionable insight that cab be acted upon with minimal disruption

- have strong senior management support.

UPDATE 26 July 2016: Another illustration is an analysis of parking fines which identified errors in enforcement.

UPDATE 19 August 2016: United Airlines has a safety data exploitation programme, also based on municipal law enforcement data analysis, which is driving cross-functional collaboration: United Airlines Uses Data Visualization To Improve Safety. they say:

We’re trying to push accountability and responsibility as far down to where it happens—to the front line—as possible. Being able to portray things in the granular level that we do by gate and by shift, that accountability doesn’t get upwardly delegated—it gets pushed to the front line, to where the lead who is responsible for his or her people can manage it—and not just say “That’s the cost of business.” We’re managing to zero—zero injuries, zero lost days, zero damages, zero lost resources. How we get there is through programs like this.

Observations

New York’s approach of fusing data from various sources has direct relevance to safety in complex industries, for example combining operational, maintenance and other business data. With safety plateaued in several areas (e.g. international commercial air transport and US HEMS operations) and regulators moving towards Performance Based Regulation, more sophisticated analyses methods become even more important (both for regulators and the organisations they regulate).

Prof Sidney Dekker comments on the danger that a Safety Management System can become a “self-referential system”: a system that just exists for itself and is a sponge for data but one from which intelligence never emerges.

Reviews of The Silo Effect:

- The Guardian

- New York Times

- FT

- UPDATE 18 August 2016: Savage Minds (a group blog devoted to ‘doing anthropology in public’)

UPDATE: 28 August 2016: We look at an EU research project that recently investigated the concepts of organisational safety intelligence (the safety information available) and executive safety wisdom (in using that to make safety decisions) by interviewing 16 senior industry executives: Safety Intelligence & Safety Wisdom. They defined these as:

Safety Intelligence the various sources of quantitative information an organisation may use to identify and assess various threats.

Safety Wisdom the judgement and decision-making of those in senior positions who must decide what to do to remain safe, and how they also use quantitative and qualitative information to support those decisions.

The topic of detecting weak or ambiguous signals was discussed too in this 2006 article: Facing Ambiguous Threats. There is also the concept of mindfulness (discussed by Andrew Hopkins of the the ANU).

Data has disadvantages as discussed in the article: Going with the Gut: The Case for Combining Instinct and Data

Data hide[s] biases and obscures the theories underpinning their creation and subsequent analysis. Data are prey to the propensity of their creators and communicators to bend them to their will. Often, data—and the models they feed—rely on the past as a predictor of the future. This is not so useful in an environment of complexity and turbulence.

Although being data-driven sounds like the latest and greatest business imperative, it’s actually high time to bring an appreciation of instinct and intuition back into the lexicon of business.

A recent PwC report Guts and Gigabytes appeared to lament the fact that despite the big advances in data science analytics executives are making many decisions based on instinct. Subsequently the same PwC team reported that, when asked what they will rely on to make their next strategic decision, 33% of executives say “experience and intuition”. This behavior, the authors seem to imply, ought to be eradicated, not celebrated.

Let us be clear. This is not an argument for ditching data. Our gut can be wrong and lead us astray, so we need good data to inform our feel for an issue or situation. But the reverse is also true. We need to recognize, and work with the fact,

Intuition is an area probed by cognitive psychologist Gary Klein in his books Sources of Power and The Power if Intuition. We also recommend this article: Data & Decision-Making: A match made in heaven or….?

UPDATE 15 October 2016: Suzette Woodward discusses the book Team of Teams, by General Stanley McChrystal, comparing and contrasting intelligence lead special forces operations with managing safety in healthcare (two not obviously similar domains!). She was struck by a section on intelligence. McChrystal comments: “Like ripe fruit left in the sun intelligence spoils quickly”. Woodward comments:

…think of this in terms of data related to Safety. If an incident reporting system was about fixing things quickly then by the time incident reports reach an analyst most of the information is worthless.

McChrystal goes on:

Too many the intel teams were simply a black box that gobbled up their hard won data and spat out belated and disappointing analyses.

Woodward comments:

We have all heard that one in relation to incident reporting. Our current catch all approach actually creates this problem. Of course with a mass of data every single day anything learnt is going to be belated and disappointing. What this sadly means is that it is often ignored and frankly because of this, time would be better spent doing other things. But that’s a dilemma- we can’t ignore the data but how can all the data be tackled in a timely manner.

McChrystal goes on:

On the intel side, analysts were frustrated by the poor quality of materials and the delays in receiving them and without exposure to the gritty details of raids they had little sense of what the operators needed.

Woodward comments:

This reminded me so much of the way in which we inappropriately compartmentalise safety into neat boxes with people working independently in an interdependent environment. Safety people need to be exposed to day to day experiences and at the same time appreciated and valued for what they bring.

This I would suggest is symptomatic of a larger problem; the way the whole organisation works and dare I say it the overarching system that is there to support them.

It always boils down to people and relationships in the end.

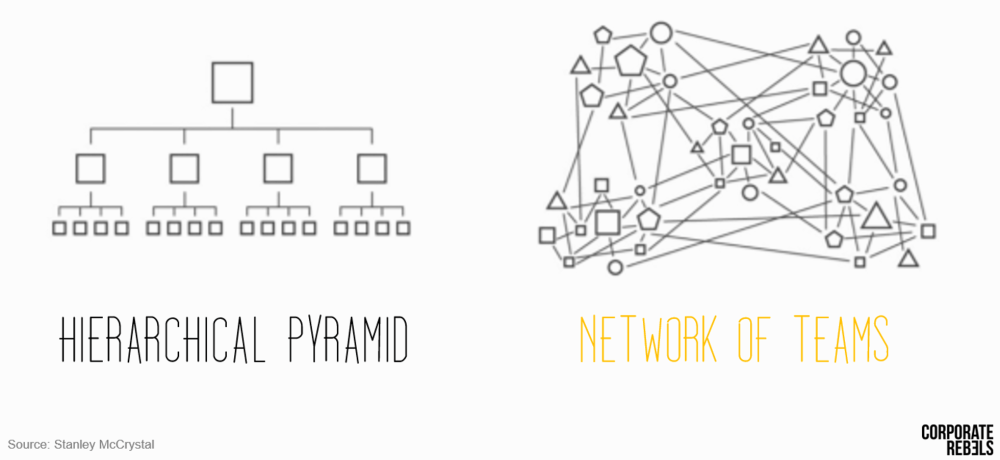

UPDATE 14 May 2017: Destroy the hierarchical pyramid and build a powerful network of teams say the Corporate Rebels:

Out of the eight trends we see, this one is the most disruptive to an organization. But because of that, it might also be the one that has the most impact on the engagement of employees and the success of an organization.

In reality, our organizations are simply not a collection of clearly distinguishable departments and roles as shown in [atraditional organisation chart]. Therefore, we should stop designing them like this. No wonder that most of the progressive organizations we’ve visited moved away from this traditional organizational structure.

Many of the progressive organizations we visit welcome a so-called “Network of Teams”.

For this to happen, we should begin to tear down our familiar organizational structures so we can start rebuilding them along more fluid lines. We need to dissolve the barriers that once made organizations efficient but are now slowing them down.

Then let us design structures that actually work and aim to distribute authority and autonomy to individuals and teams. …establish[ing] flexible structures that allow individuals to gather as members of multiple teams within multiple contexts.

They say the key learnings to start the journey are:

- Create small, multidisciplinary teams and split them when they grow over 15 members;

- Have each team craft its own purpose within the organizational purpose;

- Make teams responsible for their own results and give them a (financial) stake in the outcome;

- Create transparency to foster a healthy dose of competition;

- Leverage the power of technology to create alignment.

UPDATE 3 June 2017: Helicopter operators are increasingly data rich, but how much of it is producing value to safety, efficiency and effectiveness? In Big Data, Little Information, Mark Prior discusses how helicopter operators can extract more information from silos of data.

Recent Comments