NTSB Report on Bizarre 2012 US S-76B Ditching (N56RD)

The US National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) has reported on an unusual 2012 offshore accident where a Sikorsky S-76B ditched while attempting to land on a drilling rig in the Gulf of Mexico. This accident raises a wide range of questions…

History of the Flight

According to the NTSB:

On April 17, 2012, about 1155 central daylight time, a Sikorsky S-76B helicopter, N56RD, was substantially damaged during a forced landing in the Gulf of Mexico near the Joe Douglas oil drilling rig ([in block] Vermilion VR376A [117 nautical miles south of the refuelling point at Acadiana Regional Airport (ARA), New Iberia]). The pilot, the airplane pilot-rated passenger in the copilot seat, and the five passengers seated in the cabin were not injured.

The pilot reported that he made a visual approach on a 190 degree heading to the landing platform. He reported that the wind was from 220 degrees at 5 to 6 knots, according to the Garmin 500 GPS that was installed in the helicopter. He was flying directly towards the platform while decelerating from 60 to 45 knots while maintaining a 12 degree approach angle. The helicopter was about 60 feet from the landing pad and about 15 to 20 feet higher than the landing pad with a nose high attitude in the flare when a loss of engine power occurred. The pilot was unsure which engine had the loss of power. With the loss of power, the pilot reported that the trajectory of the helicopter would place it short of the landing pad. The pilot reported that the helicopter was going to hit the platform, so he pulled collective pitch, banked aft and to the left to avoid contact with the platform. Once clear of the platform, he attempted to lower the collective and gain airspeed, but the helicopter was in a high rate of descent with low airspeed. He pulled collective pitch and flared the helicopter before water impact. The pilot reported about 3 to 4 seconds transpired from the time he tried to avoid hitting the platform to when the helicopter impacted the water.

Inexplicably, rather than shut down and evacuate the aircraft, the pilot kept power on and after inflating the floats [emphasis added]:

…attempted to water taxi toward the oil platform, but there was no directional control since the tailboom was partially separated from the fuselage.

The pilot continued to keep engine power on the helicopter as a rescue pod [presumably a Billy Pugh style transfer basket] from the Joe Douglas was lowered to the water. The passengers in the cabin were preparing to deploy the life rafts as the rescue pod was being launched. When the rescue pod was near the helicopter, the pilot shut down the engines. The passengers deployed the life rafts as the helicopter began to list to the left. All six passengers and the pilot got into the rafts, and then transferred into the rescue pod, which was then winched back up to the deck of the platform. None of the occupants reported any injuries.

Sometime after the occupants egressed, the helicopter inverted in the water with the four floatation bags keeping it from sinking. However, the bags were compromised during the initial recovery effort and the helicopter later sank in about 310 feet of water.

The Rowan Joe Douglas Jack-Up Drilling Rig was commissioned in 2011 (Credit: Drilling Contractor)

NTSB Conclusions

The NTSB identified the Probable Cause as:

The intermittent loss of engine power due to a “stuck” stepper motor in the No. 2 engine’s fuel control as a result of an inadequate overhaul.

Contributing to the accident…

– was the pilot’s decision to continue flying the helicopter with a known defect,

– his decision to depart with the helicopter over its maximum gross weight, and

– his decision to fly the approach to the oil platform at a high gross weight in a direction that provided limited go-around potential.

The Background

The operator, RDC Marine, appears to be the flight department of the rig owner, Rowan, and the cabin fit below suggests it may have been used for management visits rather than routine crew changes. Rowan used to own offshore operator Era Helicopters, so should have had some appreciation of the risks of offshore helicopter travel, especially as their personnel were aboard for a fatal S-76A CFIT accident in 2004.

The pilot had worked for the operator for 23 years held an ATPL with ‘helicopter and single-engine land rating’s. He had a total flight time of 16,000 hours, 677 hours in the S-76B helicopters. In the co-pilots seats was an airplane pilot-rated ‘passenger’ who was a fixed wing pilot for the operator. He had not formal helicopter training, but had about 25 hours of “left seat” time in helicopters. Only having one helicopter pilot aboard no doubt influenced the sub-optimal approach as it would have been more sensible for the left hand pilot (if he were qualified) to have made the approach (see below).

A few days earlier [emphasis added]:

The pilot reported that on Friday, April 13, 2012, he was flying the accident helicopter from an oil platform to Port Fourchon, Louisiana, when the helicopter had an apparent loss of power from the No. 2 engine during cruise flight.

The pilot described the event as an engine rollback, but he was unsure about how much reduction in power the engine actually experienced….

He reported that the No. 2 engine was still operating because the N1 speed indicator (gas producer turbine) indicated that the engine was operating, but the pilot was unsure what the N1 needle read. He thought it might have been in the idle range, but he was not certain….

He reported that the No. 2 engine came back on line by itself. When it did, the No. 1 engine had a decrease in power, and the torque and temperature gauges matched up. He reported that the entire event lasted 10 to 20 seconds. After that, the No. 2 engine worked normally during the flight back to Port Fourchon.

Once at Port Fourchon, the pilot shut down the helicopter and checked for any electronic engine control (EEC) system fault codes that might have been recorded when the loss of engine power occurred. The pilot reported that there were no EEC fault codes recorded. He restarted the helicopter and performed hover and power checks. The helicopter appeared to be operating normally, so the pilot decided to continue with scheduled missions, which involved two more flights out to the oil rigs.

The pilot telephoned the mechanic and left a message about the loss of power to the No. 2 engine. The mechanic was gone for the weekend and did not check his phone messages until Sunday night. The pilot flew three flights out to the oil rigs on Saturday…

On Monday, the mechanic checked the EEC fault codes but there were none recorded. He checked the torque sensor cannon plugs and sprayed them with corrosion preventative. No engine runs or test flights were performed. No entries were made in the engine or airframe logbooks concerning the intermittent loss of power on April 13, 2012.

UPDATE: In the NTSB Public Docket the NTSB summary of the interview with the mechanic states:

1. He did not make a write-up in the engine or airframe logbook about the maintenance he had performed. He didn’t think it warranted a write-up. It was not unusual for him to not put such maintenance in the engine logbook.

2. He did not know what caused the engine rollback on Friday, 4/13. He cleaned the canon plugs because that seemed to work before. He felt he had to do at least something.

3. They have not been doing power assurance checks since the received the S-76B. They used to do power assurance checks when they had the Bell 222, but not on the S-76B.

4. There has been no trend monitoring of the engines by the mechanic.

5. About 2 months ago, the mechanic stopped rinsing the engines every day. Evidently, he was injured or sick, and since then he didn’t rinse the engines.

6. He washed the engines every 300 hours based on the fuel nozzle cleaning schedule.

On the engine failure, NTSB explain there was a maintenance error during overhaul that resulted in:

… an anomaly within the stepper motor for the No. 2 engine’s fuel control. The examination revealed that the end of the output shaft of the stepper motor had overstress fractures and that the shaft was bent. During the overhaul of the stepper motor 8 years before the accident, the pin that attaches the flapper valve lever to the output shaft was pressed onto the output shaft. The force applied to the external lever was sufficient to both crack and bend the output shaft. This condition eventually resulted in a “stuck” stepper motor which limited the fuel flow to the engine and resulted in an intermittent loss of engine power. The EECs did not monitor the performance of the output shaft or the flapper valve lever; therefore, no fault codes were generated by the EECs.

The records of the overhaul by Pratt & Whitney Canada were not available “due to an internal computer records system not migrating them to the current system”.

Wreckage After Recovery – Note Evacuation Appears To Have Occurred Through the RH Cabin Door Only and Floats Were Probably Removed on Recovery (Credit: NTSB)

The helicopter cabin also did not have an offshore fit. The executive seats have no upper torso restraints and, block the forward cabin windows, through there do not appear to have push out widows or illuminated exit lighting either.

The NTSB calculated that the aircraft took off on its final flight at 12,215 lbs, about 515 lbs over maximum gross weight. Additionally:

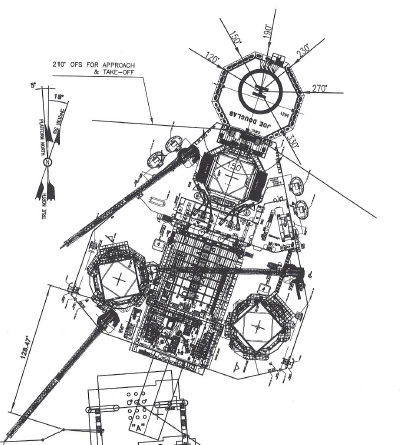

…the helicopter landing pad was located on the north side of the oil platform. An approach heading of 190 degrees, as reported by the accident pilot, put the approach path aiming for the center of the oil platform super structure. This approach angle provided limited clearance for a go-around. Likewise, an approach angle between about 160 to 220 degrees heading provided limited clearance for a go-around due to the location of the super structure. An approach path heading from about 060 to 140 degrees, or from about 230 to 320 degrees, would have provided good go-around capability since there was no super structure behind the landing platform on those headings.

The NTSB also report that the weather at the Joe Douglas was recorded only recorded daily around 1730 and not on an hourly basis. So the only record was from the day before the flight.

It is also stated in the NTSB record of witness statements that:

Another helicopter was scheduled to land on the rig later, so he was going to land toward the right edge of the landing zone.

This would have put the S-76B clearly in the 210 degree obstacle free sector and further complicating the approach for the second aircraft and leaving insufficient clearance for that size of deck (see CAP437 Chapter 3 Section 6). The deck is apparently a 22m D-value deck. The S-76 a 16m D-Value aircraft.

Further Safety Resources

Aerossurance has recently published several relevant articles in recent months:

- Helicopter Ditching – EASA Rule Making Team RMT.0120 Update

- US BSEE Helideck A-NPR / Bell 430 Tail Strike

- NTSB Recommendations on Offshore Gas Venting

- Helicopter Ditching Limitations

- Gulf of Mexico Fatal Helicopter Accident (11 Jun 14)

- Offshore Helicopter Confidence Building – Oil & Gas UK’s 2014 Aviation Seminar

- Offshore Helicopter Accident Ghana 8 May 2014 & The Importance of Emergency Response

- James Reason’s 12 Principles of Error Management

- Fatal $16 Million Maintenance Errors

- Business Jet Collides With Uncharted Obstacle During Go-Around (see re-crewing)

- UPDATE 28 January 2015: We have also now published this article: Dramatic Malaysian S-76C 2013 Ditching Video

- UPDATE 11 January 2017: Sikorsky S-92A Loss of Tail Rotor Control Events

- UPDATE 4 March 2017: Deadly Delay: GOM B206B3 Helicopter Night Accident 6 Feb 2017

- UPDATE 20 April 2017: Taiwan AS365N3 Tail Rotor Pitch Control Loss During Hoisting

- UPDATE 1 May 2017: AW139 A6-AWN Ditching off UAE, 29 April 2017

- UPDATE 3 September 2017: Night Offshore Training AS365N3 Accident in India

- UPDATE 6 August 2018: In-Flight Flying Control Failure: Indonesian Sikorsky S-76C+ PK-FUP

- UPDATE 25 April 2019: Ditching of Bristow S-76C++, Off Nigeria, 3 February 2016

- UPDATE 12 December 2020: NH90 Caribbean Loss of Control – Inflight, Water Impact and Survivability Issues

- UPDATE 9 January 2021: Korean Kamov Ka-32T Fire-Fighting Water Impact and Underwater Egress Fatal Accident

- UPDATE 16 April 2022: Helideck Heave Ho!

- UPDATE 5 June 2022: North Sea Helicopter Struck Sea After Loss of Control on Approach During Night Shuttling (S-76A G-BHYB 1983)

- UPDATE 9 July 2022: R44 Ditched After Loss of TGB & TR: Improper Maintenance

- UPDATE 17 February 2024: Night Offshore Take-Off Loss of Control Incident

- UPDATE 18 February 2024: Night Offshore Helicopter Approach Water Impact

Recent Comments