Fatal Wire Strike on Take Off from Communications Site

The Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) have released their report on a helicopter that departed a microwave communication site and fatally struck one of the microwave tower guy wires. The lack of effective risk assessment and landing site data jumps out in their report as does a casual approach to some pre-flight preparation. There are key survivability lessons too.

On 30 July 2015, Airbus Helicopters AS350BA C-GBPS operated by Canadian Helicopters (CHL):

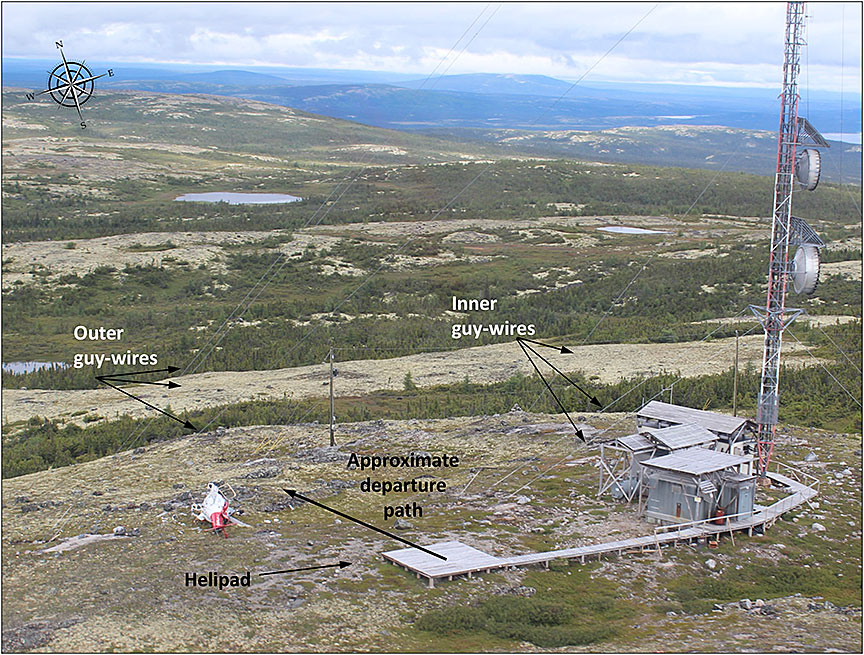

…had been flown to [the Moliak] remote microwave tower site approximately 5 nautical miles west-southwest of Rigolet, Newfoundland and Labrador, with a pilot and 2 passengers on board. At about 1609 Atlantic Daylight Time, the helicopter lifted off from the helipad at the tower site and struck a tower guy wire with the main rotor.

The helicopter struck the ground and settled on its upper right side. One passenger sustained fatal injuries, the pilot sustained serious injuries, and the other passenger sustained minor injuries.

The Circumstances of the Accident

The TSB say:

The passengers were a Bell Aliant employee and a contractor. The pilot had flown with these passengers often and they had been working together at other tower sites on the previous 3 days.

The pilot had worked at CHL since 2005 and often flew to microwave tower sites, including the Moliak site. The pilot was familiar with its layout. The last time the pilot had flown to the Moliak site was 18 December 2014.

The flight departed from CHL’s base at the Happy Valley–Goose Bay Airport at 1333 [Local Time] and arrived at the Moliak site about an hour later. The helicopter was landed facing north on the site’s raised helipad. The passengers then carried out the site maintenance for about 1.5 hours while the pilot rested in the site radio building. Once the work was completed, the passengers advised the pilot, who began preparing for the return flight. The pilot noted that the wind was light and from the north.

The pilot helped the passengers load their tools and equipment onto the helicopter. Some cargo was placed on the cabin floor behind the left front seat; the left side of the rear split-bench seat had been folded up for this purpose [inconsistent with CAR 602.86(1) for stowage].

The pilot began the helicopter start-up procedure, completed the pre-takeoff checks, and confirmed that all doors were latched and that all occupants had their seatbelts fastened.

The standard safety briefing was not conducted on the day of the occurrence [inconsistent with CAR 703.39(1)].

The pilot visually scanned the area to the left of the helicopter, was interrupted briefly by a non-operational communication made by a passenger, and then continued to scan to the right of the helicopter to ensure that the area was clear for takeoff. The pilot did not note the outer guy wires and did not include them in his departure plan. At about 1609, the pilot lifted off and began intentionally moving forward.

The helicopter was just clear of the helipad and about 2 metres above downward-sloping terrain, when the contractor touched the pilot’s left shoulder. The pilot’s attention was drawn left and he then saw the tower guy wires in front and to the left of the helicopter.

As the pilot moved the cyclic control aft and to the right to avoid the wires, the helicopter’s main rotor struck a guy wire. The helicopter rolled rapidly to the right, struck the ground and settled on its upper right side directly below the outer guy wires.

The Moliak Microwave Communications Tower Site

Bell Aliant operates 27 microwave tower sites in Labrador, all of which are accessed by helicopter.

The helipad locations were collaboratively selected with CHL and Bell Aliant management personnel over 20 years ago, and at that time no formal risk assessments were conducted. Landing site diagrams were not available to the crew at the time of the occurrence.

The Bell Aliant Moliak site is on:

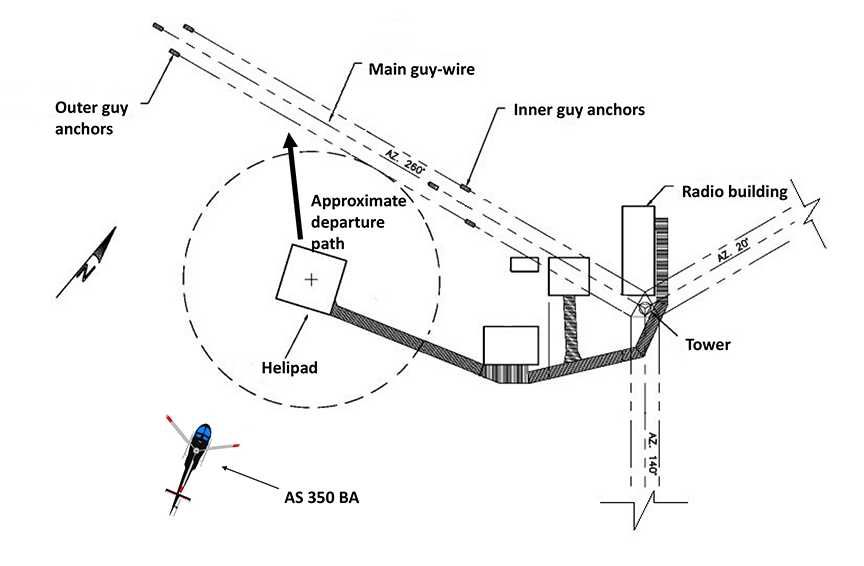

…the top of a hill at an elevation of 365 metres. The tower height is 67.1 metres above ground and is supported on 3 sides (120° azimuth spacing) by steel cable guy wires, arranged in inner and outer groups of wires. The inner group of 3 wires are anchored about 25 metres from the tower, and the outer group of 3 wires are anchored about 55 metres from the tower,

The 3 small buildings at the site contain communications and power generation equipment and are connected by raised walkways covered with wooden decking. One such walkway extends about 35 metres west of the tower to the helipad, which is a raised square wooden deck about 0.5 metre above ground level and about 6 metres square. The centre of the helipad is about 14 metres away from the closest guy wire.

The AS350 has a 13 metre D Value.

It is normal practice in a helicopter, as it is in any aircraft, to land and take off into the wind. To stay well clear of any obstructions, all company pilots flying to the Moliak microwave tower site approach and depart from the south or southwest. The pilot did not follow this normal departure practice on the occurrence flight.

Moliak is the only Bell Aliant site with the helipad located within the circumference of the outer guy wire anchor points.

The investigation determined that all of the guy wires were visible from an AS 350 helicopter when parked facing north on the helipad, but did not have high-visibility markings.

Alerting

The [Kannad] 406-megahertz emergency locator transmitter [ELT] did not activate.

…the ELT’s acceleration switch axis of detection is angled 45° down in relation to the longitudinal axis of the helicopter in the direction of forward flight. [As] the helicopter struck the ground on its right side…the ELT did not automatically activate due to insufficient impact forces along the acceleration switch axis of detection.

The occurrence helicopter was equipped with a SkyTrac ISAT-100 system. The SkyTrac system records the time and GPS position for engine start-up, takeoff, landing, and engine shutdown. To record a takeoff, the SkyTrac system requires the collective lever to be raised, and the helicopter to indicate a speed of 5 knots for a minimum of 4 seconds.

The SkyTrac system did not send an overdue notification following the collision, because the requirements to record a takeoff were not met. After the accident, the pilot selected the helicopter master electrical switch off, then depressed the emergency button on the satellite flight following cockpit interface panel….[so] an emergency notification was not sent by the SkyTrac system because it was not powered…

The survivors telephoned for assistance.

Survivability

The pilot was seated in the right front seat, the employee in the left-front seat, and the contractor in the forward-facing passenger seat located behind the pilot, on the outer right side of the helicopter.

A post-mortem medical examination was conducted on the contractor. The examination concluded that the contractor sustained fatal injuries when his upper body was crushed under the helicopter.

Both the pilot and the employee used the full 4-point [front seat] restraint system and remained restrained in their seats throughout the accident sequence. First responders found the contractor’s 3-point [rear seat] restraint system fastened and his upper body outside of the right cabin door. Following the accident, it was found that the contractor’s shoulder belt was misrouted under his left arm.

The TSB note the pilot was not wearing a flight helmet (nor is one required by regulation). They report that:

CHL strongly encourages their pilots to wear flight helmets, but does not require that they are worn unless the client mandates it.

However, pilots would have to pay 50 percent of the helmet purchase cost (CHL reimbursing the balance).

Organisational Factors and Safety Management

CHL is the largest helicopter operator in Canada. The company operates 184 helicopters from 26 bases across Canada, including 4 from the Happy Valley–Goose Bay base.

For over 30 years CHL had been contracted to provide helicopter transportation services to the Bell Aliant microwave tower sites in Labrador. This occurrence was the first wire strike for CHL at a microwave tower site.

CHL has a safety management system (SMS). The SMS is not required by regulation and its effectiveness has not been verified by Transport Canada. All employees are given initial training on SMS and recurrent training every 36 months.

CHL had completed general risk assessments for various flight operation types, including external load operations and VFR operations. [However] no specific risk assessments had been completed for flight operations into any of the microwave tower sites.

CHL did not provide any formal [single-pilot resource management] SRM training…

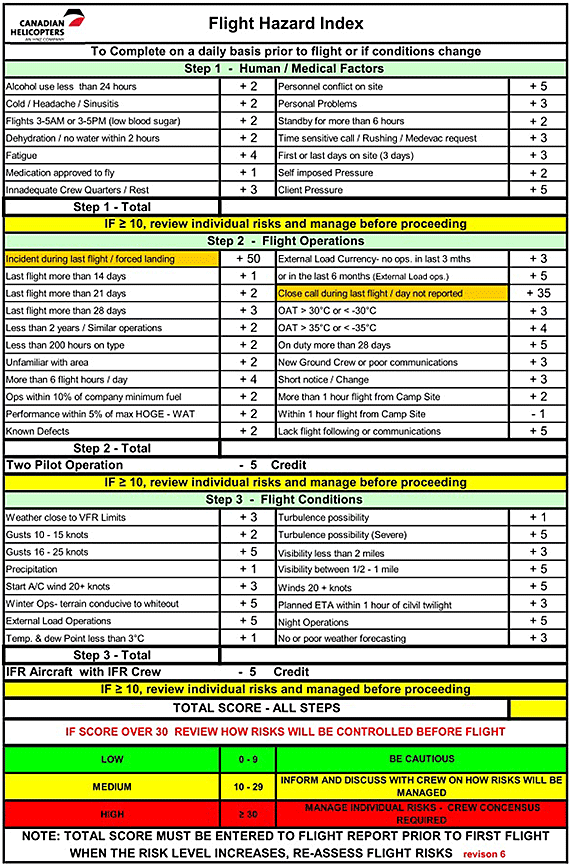

CHL uses a Flight Hazard Index card, which considers a series of human factors and flight operation conditions, to assess the level of risk associated with a particular flight.

The pilot calculated the risk score prior to the occurrence flight and assessed the total risk score to be low. The [TSB] investigation [also] assessed the level of risk using the Flight Hazard Index card; the total risk score was low. [However] the company Flight Hazard Index card does not include a flight operations condition for landing site hazards.

TSB Analysis

There was no indication of mechanical or system failure during the occurrence flight, and fatigue, incapacitation or physiological factors did not affect the pilot’s performance.

In relation to the wirestrike:

The pilot flew to microwave tower sites regularly and was accustomed to the presence of guy wires at these sites. The pilot had previously flown to the Moliak site and was aware of the proximity of the guy wires to the helipad. On the occurrence flight, the pilot did not note the outer guy wires and did not include them in the departure plan. The pilot performed a visual scan before departure; however, the visual scan was not effective in perceiving the outer guy wires. The pilot’s scan had been interrupted, which may have compromised the scan.

To be situationally aware, a pilot has to be aware of what is happening around them in order to understand how information, events, and the pilot’s own actions will impact their goals and objectives in the future—in this case, to achieve a successful takeoff. Both the routine scan and the interruption while performing the visual scan would reduce the level of the pilot’s attention, thereby contributing to degraded situational awareness. The pilot’s lower level of attention while conducting a routine flight led to an ineffective visual scan resulting in degraded situational awareness.

Company pilots depart the Moliak site to the south or southwest to remain clear of obstructions. However, on the occurrence flight, the pilot did not follow this practice and was not aware of the obstructions until being alerted by the contractor. It is also possible the pilot reverted to the normal practice of taking off directly into the wind. The helicopter struck the guy wires before evasive action could be taken, which caused the helicopter to roll rapidly and impact the ground.

During the pre-takeoff visual scan, the pilot was interrupted by a non-operational communication. This type of activity can be a distraction and can affect a pilot’s operational attentiveness during a critical phase of flight.

TSB Findings as to Causes and Contributing Factors

- The pilot did not note the outer guy wires and did not include them in the departure plan.

- The pilot performed a visual scan before departure; however, the visual scan was not effective in perceiving the outer guy wires.

- The pilot’s scan had been interrupted, which may have compromised the scan.

- The helicopter struck the guy wires before evasive action could be taken, which caused the helicopter to roll rapidly and impact the ground.

- The contractor’s shoulder belt was found to be misrouted under his left arm, which allowed his upper body to move outside of the cabin in the accident sequence and contributed to his fatal injuries.

TSB Findings as to Risk

- If the emergency locator transmitter signal is not transmitted in a timely manner, then rescue operations could be delayed, increasing the risk that survivability could be compromised.

- If cockpit or data recordings are not available to an investigation, then the identification and communication of safety deficiencies to advance transportation safety may be precluded.

- If helicopter pilots do not wear flight helmets, then they are at a greater risk of incurring head injuries in a crash and may be unable to evacuate or help evacuate the aircraft, thereby placing the safety of passengers and crew at risk.

- If a helicopter is equipped with 3-point restraint systems, then an occupant’s upper body may slip out of the shoulder belt during an accident that involves side impact forces, increasing the risk of injury or death.

- If passengers are not given a full safety briefing, then there is an increased risk that they may not use the available safety equipment or be able to perform necessary emergency functions in a timely manner to avoid injury or death.

- If carry-on baggage, equipment or cargo is not restrained, then occupants are at a greater risk of injury or death if these items become projectiles in a crash.

- If pilots are not trained in or do not use single-pilot resource management principles, such as verbalizing operational briefings, then hazards may go unnoticed and safety of flight could be jeopardized.

- If company procedures do not specify activities to be avoided when maintaining a sterile cockpit, then there is a risk that occupants may inadvertently distract the pilot during critical phases of flight.

- If occupants engage in non-essential communication while a sterile cockpit is required, then there is an increased risk of pilot distraction that may cause unintentional errors.

Other TSB Findings

- The emergency locator transmitter did not automatically activate due to insufficient impact forces along its acceleration switch’s axis of detection.

- The emergency locator transmitter was not manually activated after the collision.

- The SkyTrac system did not send an overdue notification following the collision, because the requirements to record a takeoff were not met.

- An emergency notification was not sent by the SkyTrac system because it was not powered by the helicopter electrical system when the emergency button on the satellite flight following cockpit interface panel was depressed.

- The company Flight Hazard Index card does not include a flight operations condition for landing site hazards.

Safety Actions

- Canadian Helicopters Limited (CHL) has adopted the policy of conducting an overhead inspection flight prior to landing at any Bell Aliant site. Bell Aliant employees are involved in the decision-making process and in the briefing for the approach and departure, and are asked to be vigilant during those phases of flight.

- Wire strike avoidance training has been developed at CHL and will be presented by training pilots during annual recurrent training.

- CHL has adopted new local operating procedures with detailed overview “plates” that have been designed for each site. They show obstacle avoidance routing for microwave tower sites, tower height, magnetic north, helipads and identify guy wires.

- Following this occurrence, the helipad at Moliak was moved outside of the circumference of the outer guy wire anchor points.

- Bell Aliant collaborated with CHL to conduct reviews of all Labrador tower sites to identify hazards. The resulting mitigation includes activities such as removing old wind turbines and high brush, and installing high-visibility guy wire marking at all sites.

- A process has been undertaken to contract an independent organization to conduct risk assessments at all Bell Canada sites accessed by aircraft (sites that would not have an airport used for landing), and to audit all aviation service providers used by Bell Canada.

UPDATE 30 December 2016: This was our 8th most popular article in 2016, even though published in December 2016.

Safety Resources

Also see our articles:

- The Power of Safety Leadership

- Leadership and Trust

- Safety Performance Listening and Learning – AEROSPACE March 2017

- How To Develop Your Organisation’s Safety Culture

- James Reason’s 12 Principles of Error Management

- Back to the Future: Error Management

- What the HEC?! – Human External Cargo

- Helicopter Underslung Load: TV Transmitter

- French Skyscraper: Helicopter Underslung Load

- Keep Your Eyes on the Hook! Underslung External Load Safety

- EC120 Underslung Load Accident 26 September 2013 – Report

- Unexpected Load: AS350B3 USL / External Cargo Accident in Norway

- Unexpected Load: B407 USL / External Cargo Accident in PNG

- Load Lost Due to Misrigged Under Slung Load Control Cable Non-compliant rigging resulted in a load being lost from a Japanese AS350B1.

- Beware Last Minute Changes in Plan

- The Tender Trap – the design of aviation service tenders and contracts

FAA report: Safety Study of Wire Strike Devices Installed on Civil and Military Helicopters

UPDATE 29 July 2018: Wayward Window: Fatal Loss of a Fire-Fighting Helicopter in NZ Investigators describe how the sudden loss of a window as a consequence of flying in a prohibited configuration may have made the pilot pitch up, allowing the under-slung fire-fighting bucket to strike the tail rotor.

UPDATE 29 October 2018: Firefighting Helicopter Wire Strike A helicopter was saved by cable cutters / WSPS and an evasive manoeuvre when it struck wires near dusk when firefighting.

UPDATE 13 July 2019: Helicopter Wirestrike During Powerline Inspection

UPDATE 21 February 2020: Fatal MD600 Collision With Powerline During Construction

UPDATE 5 March 2020: HEMS AW109S Collided With Radio Mast During Night Flight

UPDATE 30 May 2020: Fatal Wisonsin Wire Strike When Robinson R44 Repositions to Refuel

UPDATE 26 July 2020: Impromptu Landing – Unseen Cable

UPDATE 20 September 2020: Hanging on the Telephone… HEMS Wirestrike

UPDATE 23 January 2021: US Air Ambulance Near Miss with Zip Wire and High ROD Impact at High Density Altitude

UPDATE 5 March 2021: Wire Strike on Unfamiliar Approach Direction to a Familiar Site

The European Safety Promotion Network – Rotorcraft (ESPN-R) has published this video and guidance with EASA:

EHEST Leaflet HE 3 Helicopter Off Airfield Landing Sites Operations

Recent Comments