Human Factors of a Mali Mid-Air Collision (MAC): ALAT Tiger and Cougar, Operation Barkhane, near Ménaka

On 25 November 2019 two French Army helicopters, Airbus EC665 Tiger (Tigre) HAD 6017/F-MBJQ and Airbus AS532UL Cougar 2272/F-MCGE, collided in mid-air during a combat operation as part of Operation Barkhane, near Ménaka in Mali. The two crew of the Tiger and the 11 occupants of the Cougar died in the accident.

The Events Leading to the MAC

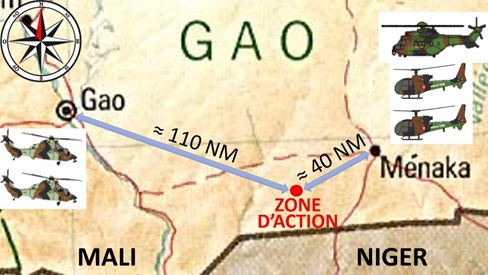

Investigators of the BEA-Etat (BEA-E) explain in their safety investigation report (issued on 29 January 2021 in French only) that at around 17:00 Local Time helicopter crews at bases in Gao and Ménaka were put on alert after a ground unit had contact with the enemy. The intention was to launch two Gazelles from Ménaka and two Tigers from Gao. With four aircraft deployed it was decided to also deploy a Cougar from Ménaka with an Air Mission Commander (AMC). The Cougar also had six troops onboard to provide an IMEX, immediate extraction, capability.

The Gazelles departed at 17:31 followed by the Cougar at 17:40. The Tiger’s departed at 17:37. This was to be a night operation, sunset was at 17:16, with the crews utilising Night Vision Googles (NVGs) and operating only with formation lights (visible from above and behind only).

The Gazelles arrived on-scene at 17:50, followed by the Cougar 10 minutes later, with the Tigers expected at c 18:25.

French troops were to the south side of a wadi (a small river valley). The engagement had had triggered a large ground fire to the north of the wadi and the helicopters from Ménaka initially search for enemy combatants fleeing behind the fire. The Gazelles identified a point of interest, called a zone of action (ZA), several miles north of the fire. At 18:19 the AMC…

…asked the Tigers and Gazelles to stay north of the area, the Tigers to stay west of the wadi and the Gazelles to the east. All of the following AMC communications relate to mission management and rules of engagement, in relation to ground troops who insistently request fire, and the Ménaka command post. The Cougar then goes north then east to fly over the wadi east of the ZA.

At 18:23 the leader of the Tiger flight announces that he will climb to a height of 2,000 ft (i.e. around 3,000 ft AMSL) and loiter 2 nm west of the area (by implication ZA).

The Cougar and Tigers coordinate TACAN channels and a pressure setting of 1,013 hPa. At this point the Cougar is at 3,000 ft AMSL and the Tigers at 2,800 ft. The AMC then proposes a withdrawal of the Gazelle and the Cougar as no longer necessary.

At 18:26 the Tigers and the Cougar had all climbed slightly, with the Tigers 2 nm west of ZA and the Cougar 8 nm to the north-east. Shortly after the Cougar crosses the wadi and heads south-west without announcing this movement.

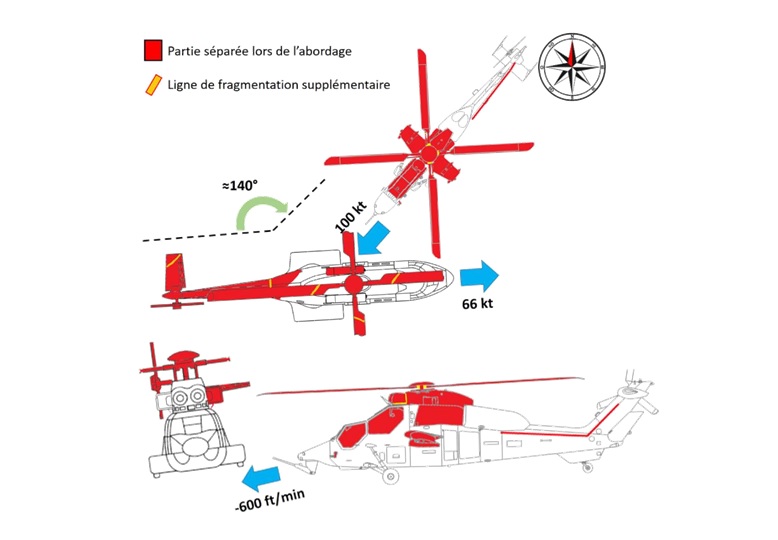

At 18:29 the Tigers split so that one aircraft can overfly French troops at their request. The AMC is however busy on another channel at this point. The lead Tiger goes into an orbit around ZA at 3,000 ft before climbing to 3,300 ft. The Cougar, still at 3,200 ft, now commenced its unannounced orbit of ZA. At 18:33 the Cougar and lead Tiger passed in opposite directions separated 300 m horizontally and 100 ft vertically at 66 and 100 knots respectively. Two minutes later, on the opposite side of their orbits, the two aircraft collided.

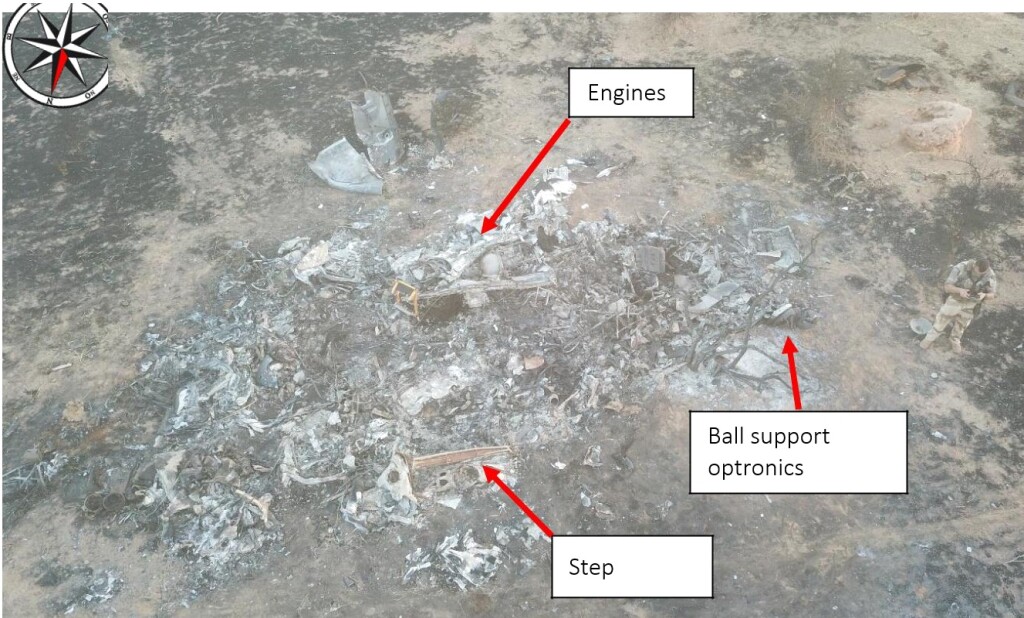

The wreckage was spread over about a kilometre and both fuselages caught fire.

Safety Investigation

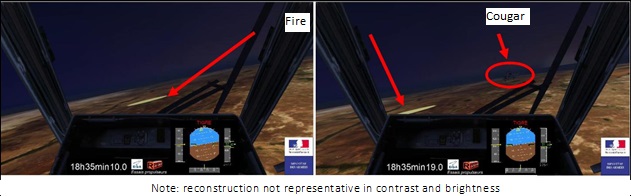

BEA-E were able to reconstruct the pilot’s view point just prior to impact.

Tiger Pilot’s View 10s and 1s Before Impact: ALAT Cougar / Tiger MAC Impact over Mali (Credit: BEA-E)

Cougar Pilot’s View 10s and 1s Before Impact: ALAT Cougar / Tiger MAC Impact over Mali (Credit: BEA-E)

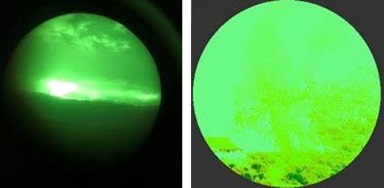

The fire on the ground was directly ahead of the Tiger and its light would have significantly degraded NVG performance.

The Effect of a Ground Fire on NVG Performance – Distant vs Close: ALAT Cougar / Tiger MAC Impact over Mali (Credit: BEA-E)

The Cougar was masked too by window pillars for a few moments. Both aircraft’s formation lights were also masked to the other. The FLIR fitted to each aircraft were both aimed at the ground and so neither would have detected the other aircraft. BEA concluded that:

In the visual environment with which they were confronted, the crew of the two aircraft neither perceived any visual indication of the presence of the other aircraft in the vicinity, nor its final approach and therefore the imminence of collison.

The investigators concluded that the Tiger pilot believed the Cougar was still to the east of the wadi. The Cougar crew however appear to have been confused when the two Tigers had split and may have assumed that both had headed south. The BEA-E discuss the process of developing situational awareness:

In the context of a combat operation with many actors, which constitutes a complex, dynamic and risky operation, and due to the lack of a dynamic positioning system for the actors, it is difficult for the crews to maintain awareness of the current situation.

A mistake can easily be made and can remain difficult to detect.

During these missions, decisions are taken under time pressure, under constraints and with the resources of the moment. They are the result of the cognitive compromise worked out in the moment by the operator to face the situation encountered. If, a posteriori, these decisions can sometimes be considered as non-optimal by an outside observer, they nevertheless remain the solution adopted by the operator in order to best manage the often contradictory objectives that he has to achieve and the risks that he must face.

It is under these conditions, to the limits of human perceptual and cognitive capacities, but also to the limits of technological and organizational capacities of the moment, that it is necessary to have clear and obvious clues allowing to realize an error in the mental representation of the situation that everyone maintains. Each crew member maintains his mental representation following a process “from above”: with a search for information according to what is expected of the situation and what we have understood of this situation. Indeed, in the phases of the activity where the workload is important, it is impossible for the operators to process all the information present in their environment. Also, as long as the information perceived corresponds to the situation expected by the operator, the remaining cognitive resources will be used by the operator for other tasks.

It is only when clues indicate to the operator that his mental situation does not correspond to the real situation that he will have recourse to a process “from below” with which one seeks information to understand the situation and anticipate its evolution, in order to reconstruct a correct mental situation.

Neither helicopter was equipped with any form of Airborne Collision Avoidance System (ACAS) and their TACAN only presents the distance between cooperating aircraft without any alarm or alerting capability and without indicating the bearing.

BEA-E comment:

The absence of a useful aid system for the detection of surrounding aircraft and for the prevention of collisions, in the very degraded visual environment at the time of the event and in the context of a combat mission with aircraft lights intentionally extinguished, render the application of the “see and avoid” rule for the detection of an impending collision ineffective.

The prevention of collisions during the event relies solely on monitoring the TACAN distance and on verbal communication to coordinate.

The probable focus of the crew members on the objective and the ground mission, as well as their erroneous awareness of the situation, led to insufficient monitoring of the TACAN, the use of which in the context of deconfliction is not formalized [in procedures].

Under the conditions of the event, communication between the crews is almost the only barrier to prevent the accident… The situation is inherently fragile and therefore not very tolerant of error.

However, BEA-E explain:

Six months before the event, after several dangerous rapprochements, the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) alerted the GTD-A [Desert battle group – air combat] of the imminent risk of mid-air collision of aircraft in northern Mali. One incident notably took place in Gao where a Tiger and another taxiing aircraft almost collided on the ground at night. The safety plan for the current GTD-A mandate mentions this risk, but limits it mainly to coordination with non-GTD-A aircraft, on the Gao ramp in particular; the considered risk of collision between GTD-A aircraft is limited to the case of towing aircraft on the ground.

The partial order of the operation in progress (fragmentary order or FRAGO) does not provide any explicit precision on internal in-flight coordination… The case of joining aircraft from different bases (Gao and Ménaka) is notably not addressed. The decision to take into account an altimeter setting at 1,013 hPa, due to the absence of a weather station in Ménaka and to be able to coordinate aircraft of different origin (Gao or Ménaka), was communicated to the crews orally during briefings previously but does not appear in these instructions.

The ALAT [Army Light Aviation] operations manual defines the responsibilities of crew members for collision avoidance surveillance but does not provide the methodology for ensuring it. In the “collision prevention” paragraph, it refers to the dedicated texts of the staffs, departments and management bodies in particular, each at their own level, to define the procedures for preventing collisions between aircraft.

The EALAT [ALAT School] courses mention that a vertical seperation can be set up between aircraft and recommend a minimum seperation of 500 ft at night. However, no value is imposed and the decision is left to the patrol leader or AMC.

The management of the risk of collision in flight therefore relies entirely on the crews…but without any specific procedure or instruction to apply….

In this case the crews departed from two locations without the opportunity for a common briefing.

In the absence of a common safety briefing and an explicit reference safety framework allowing upstream communication of safety instructions, the coordination in operation between the helicopters coming from different bases is entirely dependent on the decisions taken on site and turns out to be insufficient in practice.

Furthermore, the investigators observe that there was a breakdown in use of standard phraseology during the operation. For example radio calls were made without call sign. There was also no standard geographic reference points used and ambiguities. Additionally, the repositioning of the Cougar and the splitting of the Tigers were not, respectively, communicated and understood. The BEA-E observe this is partly explained by a heavy mental workload during a complex tasking and an assumption that other crews knew their intentions. This was exaggerated by the use of multiple channels and parallel discussions. The lead Tiger also suffered from several minutes of erratic communication problems in the minutes before impact which increased workload and distracted attention.

On the Tiger Patrol Leader’s experience level, the BEA-E note that:

The training of ALAT officers provides for them to be qualified as a patrol leader at the end of their initial training course. The Tiger Patrol Leader has been posted to a unit for barely a year after completing his pilot training. Given this still limited experience, it is likely that his expertise was still developing, both on the aircraft and with regard to his duties as captain and patrol leader. …this poorly consolidated expertise makes reaching a state of cognitive overload faster.

In the minutes preceding the accident, the Tiger patrol leader successively went through a dense tactical briefing with the Gazelle patrol leader, the management of a radio problem and the management of his detached wingman for the benefit of the ground troops…. Following his message at 18:30 to indicate his position and altitude, he concentrated on the operational aspects of the mission.

The BEA-E comment the Tiger patrol leader “no longer has the capacity to perform the tasks of monitoring trajectory and collision avoidance”, though of course he believed his was the only aircraft close to ZA.

In view of the complexity of the tactical situation at the time and the modest experience of the Tiger Patrol Leader, a state of cognitive overload is probable and may have adversely impacted fluid and complete communication with its pilot to ensure safety. In fact, it cannot contribute more to the synergy of the module.

In relation to the AMC, the BEA-E observe that it was difficult to quantify his actual experience in that specific role.

In addition, the AMC has acquired his experience as flight crew mainly on Tiger helicopters and he is much less familiar with the Cougar, especially as an AMC operating in the cabin. During the first part of the flight, he is thus obliged to request the flight engineer for each change in radio frequency. On several occasions he does not press the PTT correctly and has difficulty sending his message.

Consequently, he appears to have avoided frequency changes and relied on the Cougar commander to pass on messages. The BEA-E comment that the AMC did not actively address deconfliction matters:

As a result, the Tiger and Gazelle patrol leaders coordinate with each other but care less about the Cougar, whose last position they know seems distant.

Intriguingly they also say:

In his previous post, the AMC was confronted with an operational event concerning the rules of engagement which had a strong psychological impact on him. This is why it focuses on the ground mission, the issue of compliance with the rules of engagement and viewing the camera images, with strong pressure from the troops on the ground.

Thus, he is less available to deal with the deconfliction, which he may think he handled through his message when the Tigers arrived. To free himself from mental resources, he delegates this management to the captains and the patrol leaders, but he only informs the Cougar commander of this delegation. In particular, he does not inform the JTAC (Joint Tactical Air Controller on the groumnd], who was trained to take over the management of aircraft deconfliction.

This focus did at least cause the AMC to realise that the air assets deployed were in excess of what was needed, however this required approval from a higher command level, triggering communication outwith the operation. The BEA-E comment that a lack of delegation to the AMC on this point was “detrimental to aviation safety”.

Furthermore, three people on board the Cougar were concentrating on the imagery to resolve the rules of engagement dilemma. The BEA-E note that while specific crew resource management (CRM) training was included in the night module of Cougar operational training available to be delivered pre-deployment, this had not been delivered to this crew.

BEA-E Conclusions

The collision could not be avoided because the crews did not detect the presence of the other aircraft. Their respective awareness of the situation was wrong. The causes fall exclusively within the domain of organizational and human factors.

In the highly dynamic, complex and risky context of a combat operation, security relies mainly on the coordination of aircraft and therefore on communication. The crews developed an erroneous situational awareness leading to an imminent risk of collision situation, due to poor coordination and communication…

The BEA-E make 19 safety recommendations as a result of this investigation.

UPDATE 24 November 2022: A US Navy Sikorsky MH-60R Seahawk and a civil fire-fighting UH-60A Black Hawk collided during a night exercise.

Safety Resources

The European Safety Promotion Network Rotorcraft (ESPN-R) has a helicopter safety discussion group on LinkedIn. You may also find these Aerossurance articles of interest:

- AAIB Highlight Electronic Conspicuity and the Limitations of See and Avoid after Mid Air Collision

- Military Mid Air Collisions

- Military Airprox in Sweden

- North Sea S-92A Helicopter Airprox Feb 2017

- Mid Air Collision Typhoon & Learjet 35

- USMC CH-53E Readiness Crisis and Mid Air Collision Catastrophe

- Avoiding Mid Air Collisions: 5 Seconds to Impact

- Fatal Biplane/Helicopter Mid Air Collision in Spain, 30 December 2017

- A319 / Cougar Airprox at MRS: ATC Busy, Failed Transponder and Helicopter Filtered From Radar

- Merlin Night Airprox: Systemic Issues

- Alaskan Mid Air Collision at Non-Tower Controlled Airfield

- Mid-Air Collision of Guimbal Cabri G2 9M-HCA & 9M-HCB: Malaysian AAIB Preliminary Report

- Culture and CFIT in Côte d’Ivoire (ALAT SA342M Gazelle)

- UPDATE 15 May 2021: Military SAR H225M Caracal Double Hoist Fatality Accident

- UPDATE 5 June 2021: SAR AW101 Roll-Over: Entry Into Service Involved “Persistently Elevated and Confusing Operational Risk”

Recent Comments