The Jet that Almost ‘Landed’ on a Tower Block

On 16 August 2007 an airliner on a night approach at Dublin lined-up not on the runway but on the lights of a tower block. We look at the investigation, the lessons and the prompt safety action taken.

The Incident Flight

The McDonnell Douglas DC-9-83 (MD-83) G-FLTM, of now defunct British airline Flightline, had departed Lisbon for Dublin with 118 people on-board and the Co-pilot as Pilot Flying (PF).

According to the investigation report of the Irish Air Accident Investigation Unit (AAIU):

The flight progressed without incident until commencing its approach to Dublin Airport.

The NOTAM for Dublin clearly indicated that the main RWY 10-28 would be closed later that evening for maintenance. Despite having the NOTAM.. the Flight Crew…briefed for, a standard descent and ILS approach on RWY 28.

RWY 34 was in fact in use and during decent the Automated Terminal Information Service (ATIS) message alerted the crew.

The track distance for descent was now considerably shorter [than the crew expected] and the Flight Crew had to brief and prepare for a non-precision approach on RWY 34.

The approach was made at night; the weather and visibility were good.

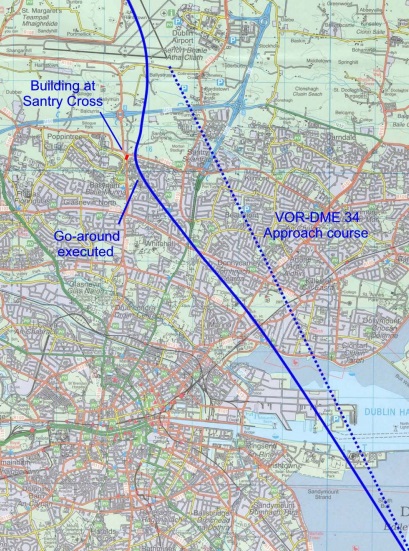

During the approach, at approximately 5 nautical miles (nm) from touchdown, the aircraft began to deviate left of the approach course.

The Flight Crew misidentified other lighting in urban Dublin as that of RWY 34 (we discuss that lighting below).

The PF, contrary to the Company SOP, looked out early for visual reference, and saw almost straight ahead what appeared to be the approach lightning of RWY 34.

However:

With the wind from 260º at 12 kts, the aircraft would have been on a heading of 336° to make good a track along the inbound course of 342°.

The aircraft was thus pointing to the left and towards the ‘false’ lighting.

The Auto Pilot remained engaged and the heading was adjusted to the left by the PF. The aircraft was then turned further left, steering the aircraft away from the required inbound course. Descent was continued with crossing altitudes checked by the PNF.

The PNF, checking the crossing altitudes, stated that the aircraft was ‘too high’ but the PF was looking at what he considers to be the PAPI, which indicated an apparent ‘all red’ or ‘too low’ indication. At that moment there was considerable confusion on the flight deck.

Meanwhile the Air Movements Controller (AMC) was the sole occupant of the Tower as the Surface Movements Controller (SMC) had left almost 20 minutes earlier at 23:15 as the traffic level was so low. The AMC was however distracted by radio calls from construction vehicles working on the closed runway.

The aircraft continued to descend below the Minimum Descent Altitude (MDA) without proper visual identification of the runway…. [The PF] was puzzled by the absence of runway edge lights beyond what appeared to be the touchdown point. He queried ATC as to the status of the runway lights and immediately the Tower controller issued instructions to turn right and climb.

The aircraft had descended to 580 ft above mean sea level (AMSL) before executing a go-around.

When [subsequently] asked why he [the PF] did not execute a go-around [himself], he said he considered it to be a decision for the Commander. He only executed a go-around on the direct instruction of ATC.

At the point the go-around commenced, the aircraft was approximately 1,700 ft from the [false lighting] and 200 ft above it. On the instructions of ATC the aircraft turned right and climbed to a safe altitude.

The aircraft landed safely on the second approach.

On completion of the flight no de-brief concerning the incident took place between the Commander and Co-pilot. The Tower Controller filed an Occurrence Report following the end of duty. The event was logged as a reportable occurrence, but it was not classed as serious.

AAIU Investigation

The following day, local radio discussed a low flying airliner. Enquires by the AAIU determined a Serious Incident had occurred and a Formal Investigation was commenced. Flight Data Recorder (FDR) data was available but the Cockpit Voice Recorder (CVR) data has been overwritten.

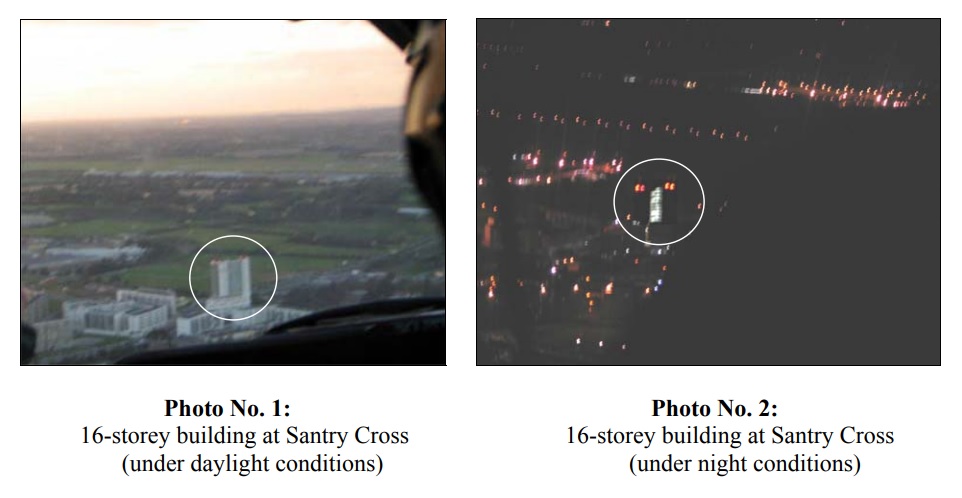

The AAIU used an Irish Air Corps helicopter to make trial approaches to determine what the pilots had actually seen.

It was readily apparent…that under night conditions, the lighting on the 16–storey [hotel] building at Santry Cross, resembled the approach lighting on RWY 34.

This building, has an overall height of 52.75 metres (m) and an elevation of 116 metres…and penetrated the Inner Horizontal Surface of Dublin Airport by 4 m.

As a result, the Aerodromes and Airspace Standards Department of the IAA issued instructions to the Architects regarding the requirements for lighting the structure under ICAO Annex 14.

It was also evident that, under night conditions, the approach lighting can be difficult to identify due to extraneous lighting from the city environs on this approach.

Photo No. 3 shows the RWY 34 Approach lighting as it would appear to an aircraft on finals. The aircraft is now on a 3-degree visual descent path, with guidance to the Pilot being provided by PAPI, indicating white/red either side of the RWY.

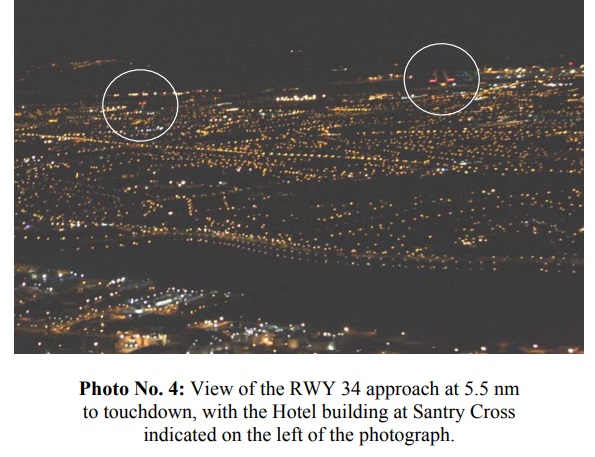

Photo No. 4 illustrates the visual picture of the approach, at a distance of 5.5 nm to RWY 34, with the Hotel and Approach lights both visible. As this distance from the runway, the PAPI’s indicate all red as the aircraft is below the visual profile.

Safety Actions

Following a briefing by AAIU on 4 September 2007 on their findings and two planned safety recommendations (less than 3 weeks after the Serious Incident)…

…the IAA issued Air Traffic Services (ATS) Operations Notice 043/07 [highlighting in particular that the fixed red obstacle lighting could be mistaken by a Flight Crew for runway approach lights. The IAA also undertook to review the obstacle lighting scheme installed on the building. On Monday 8 October 2007, the obstacle lighting was changed from fixed red lights, to flashing red.

So a physical change was made in just 7 weeks.

AAIU Analysis

The AAIU say that:

…any assessment of new obstacles, or other lighted projects such as roads that are within the prescribed distance from an aerodrome, should include a general risk analysis. This analysis should include an assessment of the visual impression that such objects may present to pilots, when lighted at night.

The AAIU found that the approach lighting was not easy to identify at a distance amongst other urban lighting. While the runway lighting brilliance can be turned up by ATC, this would be too bright for the final approach and landing flare.

The PNF who was the aircraft Commander was not in control of the situation. The confusion and ambiguity arose as both pilots had a different and inconsistent ‘picture’ of the situation. This state of affairs was enough on its own to immediately execute a go-around, as the situational awareness of the Flight Crew was now seriously compromised-contrary to company procedures.

AAIU Conclusions

Probable Cause

The decision of the Flight Crew, to continue an approach using visual cues alone, having misidentified the lights of a building with the approach lights of the landing runway.

Contributory Factors

1. The fixed red obstacle lighting on the roof of the building, together with the white internal lighting, resembled the approach lights of the landing runway when viewed from the approach path.

2. The failure of the Flight Crew to follow Company Standard Operating Procedures.

3. Poor CRM of the Flight Crew.

4. Communication with Maintenance Crews on RWY 10-28 distracted the AMC at a crucial time during the approach, while the AMC was the sole occupant of the Tower.

Safety Recommendations

The final report made three safety recommendations:

1. The Operator undertake a comprehensive review of the CRM training provided to its Flight Crews. (SR 08 of 2009)

AAIU Comment: The Operator went into administration on 3 December 2008. The Joint Administrators stated in a communication, dated 29 January 2009, that they would not be taking any action in response to this Safety Recommendation.

2. The IAA examine the manning levels of the Tower at night, and during periods of routine maintenance. (SR 09 of 2009)

3. The IAA, when considering the type and positioning of warning lights specified for an obstacle in the vicinity of an aerodrome, should take account of the potential for confusion by pilots of such lights with visual navigation aids at the aerodrome. (SR 10 of 2009)

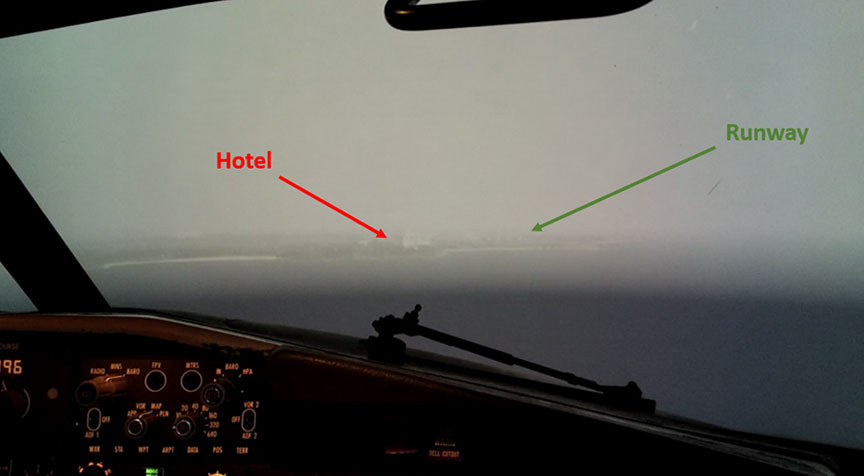

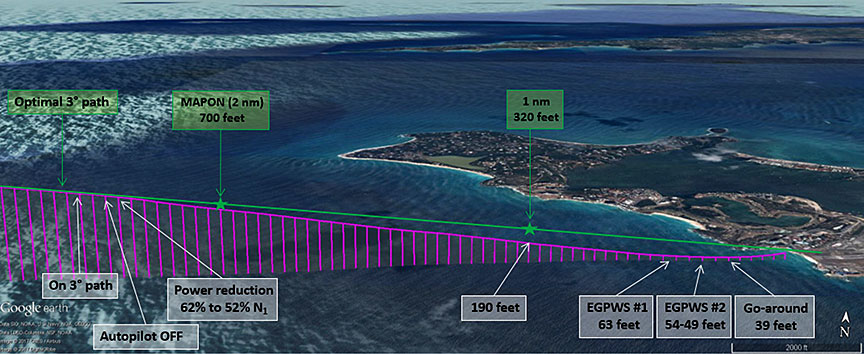

UPDATE 4 June 2018: The TSB of Canada issued their report into a near collision with the sea of WestJet Boeing 737-800, C-GWSV at Princess Juliana International Airport, Sint Maarten.

The occurrence of a moderate to heavy rain shower, after the aircraft crossed the missed approach point, led to a significant reduction in visibility. The low-intensity setting of the runway lights and precision approach path indicator lights limited the visual references that were available to the crew to properly identify the runway.

The features of a hotel located to the left of the runway, such as its colour, shape, and location, made it more conspicuous than the runway environment and led the crew to misidentify it as the runway.

Visual references as seen in a flight simulator at approximately 500 feet AGL in poor visibility (Credit: TSB)

At 1534:03, when the aircraft was 63 feet above the water, the aircraft’s enhanced ground proximity warning system (EGPWS) issued an aural alert of “TOO LOW, TERRAIN” and the PF increased the pitch to 4° nose up. The aircraft continued to descend, and a second aural alert of “TOO LOW, TERRAIN” sounded as it passed from 54 feet to 49 feet AGL.

At 1534:12, when the aircraft was 40 feet above the water and 0.3 nm from the runway threshold, the crew initiated a go-around. The lowest altitude recorded by the EGPWS during the descent had been 39 feet AGL.

Standard 3° angle of descent versus the aircraft vertical approach path (Credit: TSB)

We have previously discussed two unrelated MD-80 accidents in service:

- ValuJet Flight 592: 11 May 1996

- Delta MD-88 Accident at La Guardia 5 March 2015

- UPDATE 20 August 2017: 1980 MD-81 Flight Test Accident Video

Aerossurance sponsored the 2017 European Society of Air Safety Investigators (ESASI) 8th Regional Seminar in Ljubljana, Slovenia on 19 and 20 April 2017. ESASI is the European chapter of the International Society of Air Safety Investigators (ISASI).

Aerossurance is pleased to be supporting the annual Chartered Institute of Ergonomics & Human Factors’ (CIEHF) Human Factors in Aviation Safety Conference for the third year running. We will be presenting for the second year running too. This year the conference takes place 13 to 14 November 2017 at the Hilton London Gatwick Airport, UK with the theme: How do we improve human performance in today’s aviation business?

Recent Comments