An AW109SP, Overweight VIPs and Crew Stress

On 15 December 2014 Leonardo AW109SP helicopter A6-FLP, operated by Falcon Aviation Services (FAS), sustained significant damage after taking off overloaded in Abu Dhabi, UAE. This was an unusual accident where the crew were put under considerable stress during a poorly planned and executed VIP flight booking.

Flight Preparations

The Air Accident Investigation Sector (AAIS) of the UAE General Civil Aviation Authority (GCAA) say in their safety investigation report that:

The FAS Sales Department received a phone call at 1613 LT to book a flight which would depart Emirates Palace Hotel at 1715 LT for Al Marmum Farm. The reservation was confirmed at approximately 1658 LT. The departure time was [later] changed to 1730 LT…

At the time the flight reservation was booked, no information was provided about the number or weight of the passengers. Later, FAS were told there would be six passengers. The flight was to also be conducted ‘in formation’ with an AW139, operated by a different company. The GCAA do not expand on that requirement.

Although the AW109SP is a single pilot helicopter, FAS routinely rosters a Safety Pilot (SP) for night operations. The SP was originally scheduled for another flight but, she was on duty and available to act as SP for the Accident flight. Emirates Palace Hotel Heliport [is] adjacent to the hotel. It was used primarily for the arrival and departure of hotel guests. The heliport was uncontrolled and there was no heliport landing officer (HLO).

The passengers arrived at the heliport late and in dramatic fashion:

At 1830 LT, approximately 12 vehicles arrived at the heliport with the passengers and a number of security personnel… The cars engaged in extreme manoeuvres and circled the heliport. Many people exited the vehicles and the heliport was surrounded by cars and over 20 people.

Having previously flown VIPs, the SP said that this was “the most official and intimidating scene” that she had witnessed. The SP remained outside the Aircraft with the intention of supervising the boarding of the passengers, providing a safety briefing, and ensuring that the passengers were secured in their seats.

The boarding of the passengers was conducted by their security personnel… Neither the loadsheet for passenger weights, nor the total number of passengers was available to the crew. The SP was distracted as she tried to ensure that the security personnel did not approach the tail rotor, and she was obstructed by security personnel who appeared to be determined to keep anyone, including the flight crew, away from the VIP passengers. Eventually, the SP was able to shine her torch into the passenger cabin and she noted that there were six [seated] passengers, plus one passenger who was seated on another passenger’s knees, bringing the total number…to seven. This “additional” passenger signalled aggressively to the SP to close the door and he leant over and attempted to close the door himself.

It was not possible, due to the activities of the security personnel, to provide a safety briefing, or to confirm that the passengers were secured, prior to takeoff.

Meanwhile the AW139 had departed and requested the AW109SP join it so that the formation flight could commence. The SP took her seat and told the Captain that there were 7 passengers on-board. The Captain acknowledged that information but initiated the takeoff immediately.

The Accident Flight

The AAIS explain that the helicopter took off at 1832 LT:

As the aircraft started to hover, the autopilot disengaged and the Captain instructed the SP to re-engage it. The autopilot was successfully re-engaged, but the Captain noticed that the torque was rising above 92%. The Captain mentioned to the SP that the aircraft was heavy and the SP continued to call out the engine torque readings. The aircraft was now clear of the tree line around the heliport, and the Captain elected to turn into the wind and hover taxi over the sloping ground to the adjacent heliport pad.

As the aircraft hovered over the sloping ground, there was an over-torque warning and the Captain lowered the collective slightly. However, since the warning was brief, the Captain commenced increasing power. Both pilots commented that the aircraft did not seem to be climbing. The Captain then heard another over-torque warning and noticed that the rotor speed was rapidly decreasing.

The aircraft descended rapidly and impacted a road running between the two final approach and take-off areas (FATO), beyond the sloping ground.

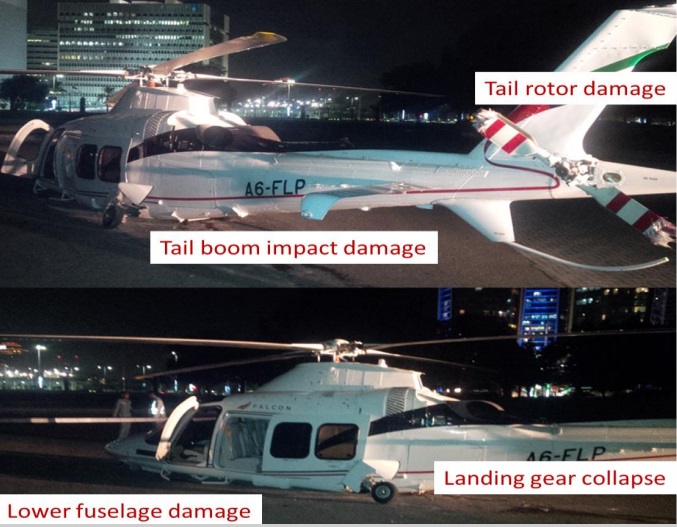

The impact caused the landing gear to collapse, the tail rotor to contact the ground and the underside of the fuselage was substantially damaged.

Falcon Aviation Services (FAS) Leonardo AW109SP A6-FLP after Impact in Abu Dhabi (Credit: GCAA AAIS)

After the impact, the SP followed the Captain’s instructions to shut down the engines, apply the rotor brake, and shut off the fuel valve.

The Captain instructed the passengers to remain seated until the rotors stopped, but they disembarked while the rotors were still turning. The rotors were considerably closer to the ground due to the collapsed landing gear.

After the Aircraft struck the ground, a number of people assembled around the aircraft and caused some confusion regarding removing the passengers from the accident site. The flight crew were unable to ascertain who had been on-board… The passengers were evacuated by the security personnel to a secure area adjacent to the hotel complex.

The GCAA AAIS were able to confirm there were no passenger injuries.  The aircraft was not fitted nor required to be fitted with flight recorders. Other aircraft systems did however record flight parameters and engine data in non-volatile memory.

The aircraft was not fitted nor required to be fitted with flight recorders. Other aircraft systems did however record flight parameters and engine data in non-volatile memory.

The data provided evidence of normal engine functioning during the entire flight. The engines responded in accordance with the collective inputs, and during the initial lift-off phase, the required engine torque was assessed at approximately 95% with a collective displacement of approximately 60%. In the subsequent seconds, the Captain increased the collective up to 70% and both engines reached a torque value of 110%. The 110% torque value is consistent with the torque limiting function being active during the flight. The torque limiter is normally inactive at aircraft power up and can be activated by the pilot using a press button on the collective control grip.

Approximately 17 seconds before the impact, as a result of the engines operating at maximum torque, the rotor rpm started to slowly decrease and the Captain reacted by applying more collective which resulted in a rotor rpm speed drop. Several seconds before the impact, the rpm had decreased to 75% with a collective input of more than 100%.

AAIS Analysis

The AAIS note that:

The SP was prevented from looking inside the passenger cabin,…unable to conduct a passenger safety briefing and did not have an opportunity to check that all of the passengers were securely restrained.

The Captain…under pressure to depart…began to initiate the takeoff despite the fact that the maximum passenger number had been exceeded by one, and that the take-off weight had not been calculated correctly.

The aircraft was heavy, and the investigation believes that this led to the autopilot disengagement and after autopilot re-engaged the torque increased above 92%, and the aircraft descend rapidly and struck the ground.

Analysis of the Captain’s statement indicated that he was under time pressure…to position the aircraft to Emirates Palace Hotel to operate the VIP flight. When the passengers arrived at the Emirates Palace Hotel Heliport, a chaotic scene unfolded involving security personnel and vehicles being driven in a fast and unusual manner around the aircraft. This…caused [the Captain] to become stressed.

Due to the many adverse aspects surrounding the flight…the capacity of the crew to make correct decisions was diminished. The normally high professional standards exhibited by the flight crew had been eroded to the point where crucial decisions were either made incorrectly, or were not made at all.

For instance, the additional passenger could have been directed to disembark. If he failed to do this, the Captain could have decided not to take off until there were only six passengers on-board. The same applied to the lack of the passenger weight information, the Captain should not have attempted the takeoff without this critical information. The Captain was informed of the unsecured passenger and repeated “seven” to the SP.

Due to the accumulated pressures of time, lack of critical flight safety information, the stressful atmosphere created by the activities of the VIP security personnel, the fact that this was a VIP flight, and the overall poor support of the operation; the Captain and the SP were placed in a position of escalating stress as one issue followed another.

We would also point out that as Anthony Hidden QC wrote in his report into the 1988 Clapham Junction rail disaster:

There is almost no human action or decision that cannot be made to look flawed in the misleading light of hindsight. It is essential that the critic should keep himself constantly aware of that fact.

AAIS Conclusions

The cause was:

…the attempted takeoff at an aircraft weight which exceeded the approved maximum take-off weight (MTOW).

Contributing factors were:

(a) Failure of the flight crew to acquire the passenger information necessary to ensure that the flight would be conducted within the certified operational and technical parameters of the aircraft.

(b) The failure of the crew to control the passenger boarding process and to take appropriate action when it was observed that the maximum allowable number of passengers had been exceeded.

(c) The operator’s lack of policy designed to mitigate the particular risks associated with VIP operations.

AAIS Safety Recommendations

To the GCAA:

- SR01/2018 Ensure that certified heliports have procedures requiring helicopter operations be controlled and have landing officers available during operations.

- SR02/2018 Provide guidelines, for inclusion in security personnel training, to VIP security organizations on the importance of adherence to flight crew safety instructions and aviation safety procedures.

To Falcon Aviation Services:

- SR03/2018 Assess the operational risks of VIP flights including boarding and cabin safety procedures.

- SR04/2018 Introduce into CRM training an emphasis on the authority of the flight crew in relation to air safety and security as this relates to VIP flights whose passengers are protected by a security detail. The training should reinforce that the flight crew have full authority in relation to all flight safety and security related aspects of the flight.

Safety Resources

- Fatal Night-time UK AW139 Accident: reinforces many important past lessons on business aviation safety, managing clients, training, human factors and learning from previous accidents.

- A case where a last minute change of plan and possible perceived pressure were partly responsible for an accident: Final Report: AS365N3 9M-IGB Fatal Accident

- Pushing on in bad weather so as not to disappoint waiting clients: CFIT Gangnam Style – Korean S-76C++ and A109E helicopter accident in London.

- Strictly Scheduled: S-92A Start-Up Incident: Under customer induced time pressures, a pilot undergoing type conversion missed a unique action that was not explicitly allocated in the operator’s procedures.

- BCA discusses some ways to say no.

- UPDATE 26 May 2018: US Fatal Night HEMS Accident: Self-Induced Pressure & Inadequate Oversight Self-induced pressure and inadequate OCC support / oversight were behind a fatal US HEMS night accident were an AS350B2 departed an unprepared landing site into IMC in which an LOC-I occurred.

- UPDATE 10 June 2018: Italian HEMS AW139 Inadvertent IMC Accident We look at the ANSV report on a HEMS helicopter Inadvertent IMC event that ended with an AW139 colliding with a mountain in poor visibility.

- UPDATE 15 July 2018: HF Lessons from an AS365N3+ Gear Up Landing

- UPDATE 25 April 2020: Fatal R44 Loss of Control Accident: Overweight and Out of Balance

- UPDATE 1 November 2020: Tragic Texan B206B3 CFIT in Dark Night VMC

- UPDATE 2 January 2021: A Short Flight to Disaster: A109 Mountain CFIT in Marginal Weather

- UPDATE 13 March 2021: S-76A++ Rotor Brake Fire

- UPDATE 11 February 2022: Erratic Flight in Marginal Visibility over New York Ends in Tragedy

Aerossurance is pleased to sponsor the 9th European Society of Air Safety Investigators (ESASI) Regional Seminar in Riga, Latvia 23 and 24 May 2018.

Recent Comments