Marine Pilot Transfer Winching Accident (Brim Aviation AW109SP N361CR)

During a night Marine Pilot Transfer (MPT) helicopter winching / hoist operation on 21 April 2014, the marine pilot being transferred, was injured.

The marine pilot was being transferred from an outgoing ship to a container vessel, inbound to Astoria, Oregon, the 222 m, 27,437 gross ton MV Northern Vigor, by AgustaWestland AW109SP GrandNew N361CR operated by Brim Aviation under Part 133 (External Load Operations) for the Columbia River Bar Pilots.

The fast flowing Columbia River divides Oregon from Washington State. The Columbia River Bar Pilots (CRBP) have been using a helicopter since 1996. Currently 70% of transfers, to ships typically 15nm out in the Pacific, are done using helicopters, the rest by pilot launch. The current AW109SP, radio call sign ‘Seahawk’, is flown with two pilots at night (one in daylight) and a winch operator for the single Goodrich hoist.

The Accident Flight

The marine pilot was lifted from the outbound vessel at 23:05 local and flown around 6 miles to the MV Northern Vigor.

The US National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) say in their report:

Light rain and night meteorological conditions prevailed, and a company visual flight rules flight plan was filed for the flight.

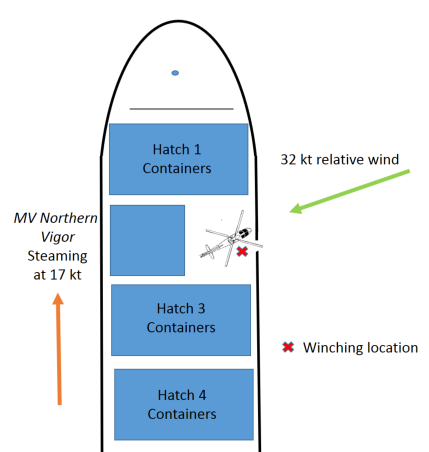

Per normal procedures, the helicopter’s crew planned to lower the ship [i.e. marine] pilot to the ship’s deck via a cable hoist while the ship was underway. When the helicopter arrived at the ship, dark night conditions prevailed, rain was falling, and the relative wind was blowing onto the starboard (right) bow of the ship.

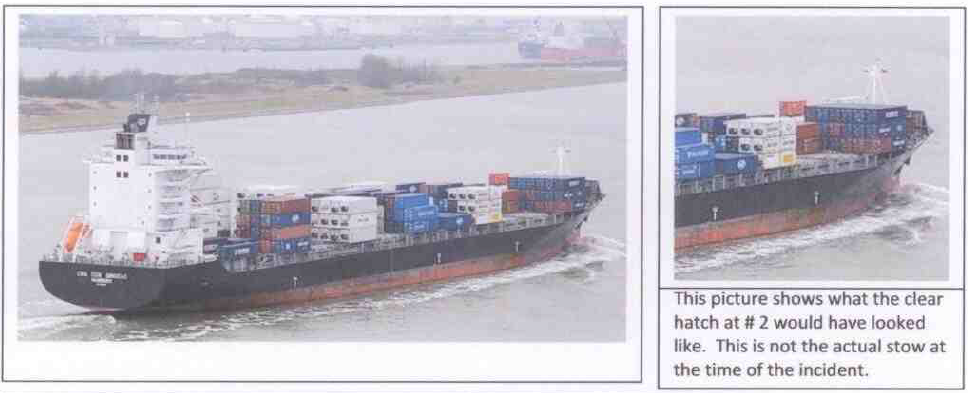

As explained in the CRBP’s report, the preference is normally to winch on to open hatch covers. However, the deck was almost completely covered by containers. The option of winching to the bridge wings was dismissed due to obstructions.

The helicopter crew circled the ship to locate a suitable location to lower the ship pilot and settled upon a location close to the starboard bow.

They identified that part of the starboard side of the Number 2 hatch was clear, albeit surrounded by containers, typically stacked two high (16ft).

The ship pilot and the helicopter crew agreed that this was the best available location for the transfer. However, this location allowed the helicopter’s pilot to see and use only a very small portion of the ship as a visual reference for maintaining the helicopter’s position while lowering the ship pilot.

The aircraft came into a hover at 20-25ft. The relative wind, the container locations, the right hand winch location and the risk of a tail rotor strike all made this choice demanding. There is no mention in the reports of the deck lighting.

Winching Area MV Northern Vigor – Scale Approximate (Credit: Aerossurance Based on NTSB/CRBP Reports)

The Pilot Flying used the forward containers as a reference while the winch operator conned him into position. At 23:18:

Just as the ship pilot made contact with the deck, the ship’s bow pitched down, and the helicopter pilot lost visual contact with the ship. Because the helicopter pilot was unable to see the ship, the helicopter began to move aft relative to the ship. The hoist operator was unable to release the hoist cable quickly enough to prevent pulling the ship pilot off the deck and had to cut the cable. The ship pilot fell a few feet to the deck…

He recovered from the fall, and successfully piloted the ship thorough the Columbia River mouth to its destination. Upon disembarkation, he went directly to the hospital, where he was diagnosed with a fractured scapula.

The NTSB note that:

The CRBP website refers ship operators to International Chamber of Shipping (ICS), a London, England-based organization which, according to its website, “is the principal international trade association for merchant shipowners and operators, representing all sectors and trades.”

ICS sells a document entitled “ICS Guide to Helicopter/Ship Operations,” which “reflects current best practice in the international shipping and aviation industries.” The guide contains “extended guidance regarding the role and responsibilities of both the ship and helicopter,” and the ICS recommends “that a copy is carried on board every ship.” The investigation did not determine whether the shipping company was a member of ICS, whether the ship was aware of, or complied with, any of the ICS transfer procedures, or whether a copy of the guide was available to the ship’s captain and crew.

NTSB Probable Cause

The NTSB determined this as follows:

The decision by the ship pilot and the helicopter crew to lower the ship pilot to a location on the ship that did not provide the helicopter pilot with an adequate view of the ship.

Contributing to the accident was the inadequate pre-mission coordination between the ship, the ship pilot agency, and the helicopter operator.

Safety Recommendations

As is common the NTSB make no recommendations in this helicopter report but they do publish the results of the CRBP investigation. That report cited four ‘Lessons Learned’ (the first two being highlighted by the NTSB):

- One recommended that ship and helicopter crews make “every effort” to establish an agreed-upon “safe place” on the ship for the hoist. This plan includes the request for the ship to fax the “stow plan [ship’s deck and cargo layout]” to the helicopter operator to aid in that coordination and determination.

- Another that some of the ship’s crew be on stand-by at the location of the planned hoist operation (they were not in this occurrence because of the impromptu hoist location).

- Wearing of helmets was shown to be of value (the marine pilot found paint marks on his helmet, but had been protected from the impact).

- The value of the marine pilot having direct radio communications with the helicopter.

Background on the Operation

The NTSB explain that:

The Oregon Board of Maritime Pilots (OBMP) is a state agency [established in 1846] under the Oregon Public Utilities Commission that regulates the bar pilots. The Columbia River Bar Pilots (CRBP) is a private organization that provides the bar pilots for ships transiting the mouth of the Columbia River.

As discussed in a Smithsonian article:

Each of the 16 bar pilots has the authority to close the bar when conditions are too dangerous. Still, [Capt Dan] Jordan says, “When we shut down the bar for two days, trains are backed up all the way into the Midwest. And just like a traffic jam on the freeway, once you clear the wreck, it takes a long time for it to smooth out again.”

Marine Pilot Transfers involve risk. The CRBP lost a pilot in 2006 in a fatal fall into 8ºC water during a transfer from a ship to a pilot launch (when visibility was too low for a helicopter transfer), having previously suffered a fatality in 1973, and over 20 others since 1846.

Helicopter transfers bring a number of benefits discussed in this video and article linked below:

Columbia River Bar Pilots Helicopter Operations VIDEO

On average seven or eight transfers are made each day by helicopter, with some days as many as 20. The NTSB note that:

In the spring of 2015, due to port/labor contractual issues, container ships no longer use the Columbia River and its ports. It is unknown when container ships will return to the Columbia River. According to OBMP personnel, container ships accounted for about 5 to 6 percent of the commercial ships that used the Columbia River.

Survivability Matters

On the day of this occurrence the sea temperature was 10.3ºC according to US Coast Guard data in the NTSB Public Docket.

Very surprisingly, for an aircraft operating low and frequently hovering over water, N361CR is not equipped with emergency floats.

The marine pilots also wear a ‘self-inflating floatation coat’ (according to past press reports) which, is not compatible with a helicopter underwater escape (see this fatal accident were a marine auto-inflate life jacket trapped the pilot of a fish spotting helicopter). UPDATE: More conventional aviation lifejackets are seen in this 2020 VIDEO.

Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) inspectors did however note that the CRBP marine pilots do undergoing initial and recurrent hoist training (which is not a legal requirement).

Safety Resources

The European Safety Promotion Network Rotorcraft (ESPN-R) has a helicopter safety discussion group on LinkedIn. You may also find these Aerossurance articles of interest:

- UPDATE 28 April 2017: Our article is referenced in the Royal College of Art (RCA) & Lloyd’s Register Foundation Safety Grand Challenge: Safe Ship Boarding & Thames Safest River 2030

- UPDATE 18 February 2018: Fatal Fall From B429 During Helicopter Hoist Training

- UPDATE 3 April 2018: Hoist Assembly Errors: SAR Personnel Dropped Into Sea

- UPDATE 25 April 2019: USAF Helicopter Hoist Training Accident: equipment snagged on obstacle

- UPDATE 30 November 2019: Fall From Stretcher During Taiwanese SAR Mission (NASC AS365N2 NA-104)

- UPDATE 14 December 2019: Fatal Taiwanese Night SAR Hoist Mission (NASC AS365N3 NA-106)

- UPDATE 19 April 2020: SAR Helicopter Loss of Control at Night: ATSB Report

- UPDATE 2 May 2020: Sécurité Civile EC145 SAR Wirestrike

- UPDATE 27 November 2021: TCM’s Fall from SAR AW139 Doorway While Commencing Night Hoist Training

- UPDATE 19 March 2022: Offshore Night Near Miss: Marine Pilot Transfer Unintended Descent

The European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) is sponsoring a safety promotion activity on hoist operations. ESPN-R has published a training guide for hoist operators.

In 2021 the Flight Safety Foundation (FSF) BARSOHO offshore helicopter Safety Performance Requirements, which had included helicopter hoist operations (HHO) from its initial issue in 2015, was expanded to cover Marine Pilot Transfer.

Recent Comments