TCM’s Fall from SAR AW139 Doorway While Commencing Night Hoist Training (Babcock MCS Spain EC-KLM)

On 16 July 2018 Babcock Mission Critical Services Spain SAR Leonardo AW139 EC-KLM was conducting night rescue training offshore Valencia, Spain. Wind speed was low, 5 knots, and the sea was Sea State 2 (0.1 to 0.5 m waves). The aircraft was hovering, about 50 ft above a vessel when the rescuer exited the cabin to be hoisted down. They however fell from the aircraft into the sea. The rescuer was recovered by the aircraft and transferred to hospital. They suffered a serious injury, an upper crush fracture of the T12 vertebra.

The Accident Flight

On 30 June 2021 the Spanish Comisión de Investigación de Accidentes e Incidentes de Aviación Civil (CIAIAC) released their safety investigation report into this accident. This is only available in Spanish so we have translated it to compile for this summary.

The helicopter, callsign Helimer 201, was based at Valencia as part of a contracted SAR service for the Spanish Maritime Rescue and Safety Society (SASEMAR).

A routine flight was planned that night to maintain crew currency. The needs of each crew member were evaluated during the pre-flight briefing. They were prioritised based on which expiry date was closer and a suitable sequence agreed.

After starting the engines at 23:00 Local Time, the aircraft headed offshore to rendezvous with a vessel for training. On board were two pilots and two Technical Crew Members (TCMs); a hoist operator and a rescuer (aka winchman).

The hoist operator was 37 and dual qualified with 228 flying hours as a hoist operator and 746 as a rescuer. The rescuer was 34 and had 730 flying hours in that role. They are among 120 employed by the operator (70 of which are dual qualified).

In the 15 days prior, the rescuer had been scheduled for two day shifts followed by two night shifts, five days off, five day shifts, followed by the night shift during which the fall occurred. On that morning they did however perform a routine mandatory medical examination (described as a ‘stress test’) at a hospital in Valencia.

The TCMs were in the cabin of the AW139.

The cabin can be separated from the cockpit by a roller blind and has independent lighting controls. The aircraft was equipped with an advanced digital intercom system (or ICS). The rescuer also carried POLYCOM and VHF radios.

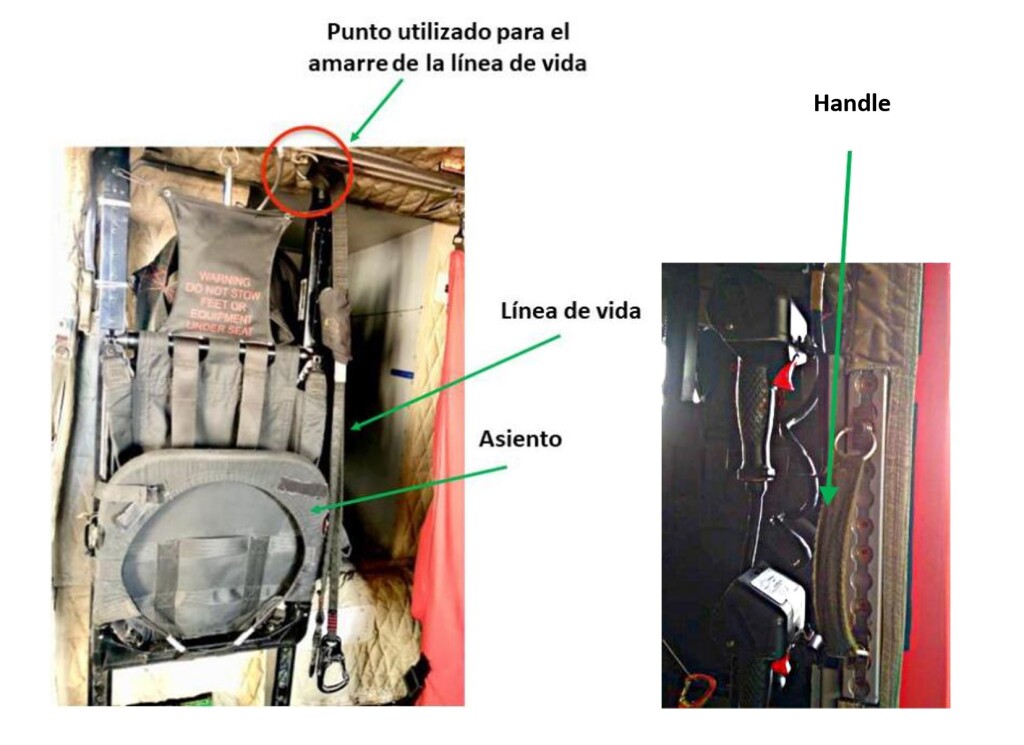

Inside the cabin there where four folding seats attached to the structure. Below is the seat used by the rescuer, showing the hardpoint where their harness lifeline is attached when they are moving in the cabin. This is one of four available to the TCMs.

Babcock MCS Spain SAR Leonardo AW139 Rescuer’s Seat & Lifeline Hardpoint (left) and Doorway Flexible Handle (right) (Credit: via CIAIAC)

A dual hoist assembly is fitted to the right-hand side of the aircraft. There is the standard cabin step below the doorway (modified to avoid hoist cable snagging). As hand holds there are flexible handles on the sides of the doorway (shown above) and a rope that runs along the upper edge of the doorway.

The training began with two approaches to hover alongside the vessel using the helicopter’s Automatic Flight Control Systems (AFCS). These were successfully completed before the next of two planned exercises; one to lower the rescuer to the vessel and then the recovery of a manakin from the water.

During the second approach the rescuer prepared their equipment for the first hoisting exercise. During the third approach the helicopter approached the vessel at 125 ft, guided by the hoist operator with the aid of the infra-red FLIR system.

After the call of ‘ON TOP’ the rescuer attached the hi-line bag carabiner to the hoist operator’s seat structure to keep it closer to hand (a hi-line is used by a vessel’s crew to pull the hook closer and to provide stability when hoisting) and hooked his harness lifeline to a hardpoint. Next, the hoist operator checked the rescuer’s equipment, communications, equipment and lifeline. When satisfied and calling that they were ready the hoist operator opened the right-hand cabin door.

At this point the hoist operator was kneeling next to the hoist controls at the front of the doorway and the rescuer seated on the floor of the cabin with the legs outside further aft.

The flight crew then activated the hoist operators’ trim control of the helicopter for the WTR (Winchman Trim) tests. This trim functionality gives the hoist operator limited horizontal control over the helicopter to enable precise positioning, while still maintaining a verbal ‘patter’ of directions to the flight crew who remain in overall control of the aircraft.

With the cabin lights now off, the hoist operator placed a chemical light on the hoist hook. The rescuer wore another chemical light.

Meanwhile, the flight crew were descending to a height of 50 ft alongside the vessel.

The rescuer recalls turning to unhook the hi-line bag from the seat and secured it to an adjacent flexible handle. There was a discussion amongst the crew about the surface conditions and downwash and the rescuer recalls examining the layout of the vessel which was being illuminated by the helicopter’s searchlight.

The rescuer believes that at this time the hoist operator presented him with the hoist hook and that he reached for the hi-line bag carabiner to attach it. The CIAIAC report is not totally clear but it appears the rescuer was under the mistaken impression that they also attached to the hoist hook to their harness at this point.

The rescuer recalls hearing on the POLYCOM that the aircraft was in position and disconnecting his lifeline in order to exit out onto the step. Then the hoist operator turned and the rescuer gave a thumbs up that they were ready.

Although being aware that the hoist operator has not yet checked their equipment, the rescuer moved outboard, turning around the hoist cable to face inwards while offering his hand out to the hoist operator for assistance. It was at this point he fell from the aircraft.

The sequence is reconstructed below:

Babcock MCS Spain SAR Leonardo AW139 EC-KLM Reconstruction of the Rescuer’s Movements (Credit: via CIAIAC)

The rescuer was equipping the drysuit and had swim fins and mask.

Babcock MCS Spain SAR Leonardo AW139 EC-KLM Rescuer’s AEA (Aircrew Equipment Assembly), the Lifeline, Hoist Hook and Hi-Line Bag (Credit: via CIAIAC)

During the fall he tried to balance his body to enter the water more vertically. The dive was not as deep as expected and he immediately noticed pain in his lower back. The rescuer’s mask was displaced by the impact. He twice tried to communicate with aircraft via radio. Initially the POLYCOM was submerged preventing transmission and furthermore the rescuer was unable to reach the VHF device.

He activated his lifejacket but was unable to activate its strobe light due to pain, poor grip in the water and the increased volume of the inflated lifejacket. Due to their fall the blue strobe light on their helmet had not been turned on either after exiting the aircraft.

On seeing the fall the hoist operator informed the flight crew. The aircraft maneuverer until the rescuer could reach the hoist hook and be hoisted aboard. Just before reaching the hook the rescuer did hear the rest of the crew via the POLYCOM.

The rescuer was transferred to the airport where an ambulance. The rescuer required three days of hospitalisation and they continued their recovery at home.

Safety Investigation

It was only on 28 May 2019 that the CIAIAC learned that the injuries suffered 10.5 months earlier met the definition of accident as defined by ICAO Annex 13 and therefore commenced their formal investigation. However, the CIAIAC say the operator had voluntarily implemented a Safety Management System in July 2008 and had already conducted a detailed internal investigation. This is the first fall from an aircraft they had experienced.

The internal investigation resulted in a series of actions directed to four departments in their organisation (summarised below):

To the Standardisation Department:

- Modification of the operational procedures so that the attachment of items to the hoist hook, is carried out individually, not simultaneously.

- Highlight in the operational procedures so that the hoist operator has to physically check the correct attachment of the rescuer (not just visually or verbally).

- Development of standard callouts in operational procedures so that, prior to the rescuer leaving the door there is a verbal verification of attachment between the hoist operator and the aircraft commander.

- Improve the wording maritime procedures in relation to the hoist attachment (aligning with onshore hoist procedure that had previously been enhanced).

To the Training Department:

- Record of a complete video of the standard procedure, step by step and fully explained, so that there are no interpretations about it between the different crews and bases. This video is now incorporated in recurrent training.

- Place special emphasis on attachment verification.

- Place special emphasis on the final checks or rescuers by hoist operators using the cabin lights and the hoist lights.

- Place special emphasis on rescuers turning their helmet’s strobe light on at the cabin exit and off just before re-entering the cabin.

- Place special emphasis on use of the FLIR CAGE position, so that it is available in event of loss of persons from the hook into the water.

To the Operations Department:

- Specify the use of the lifeline.

- Standardise the attachment points of the lifelines across the SAR fleet helicopter based on feedback from the bases.

- Standardise the lifejacket strobe lights across the fleet so they all activate automatically (there were three variants in the fleet, two were manually activated and one automatic).

- Study, with their design organisation, a suitable fixed point on the roof of the cabin for the hoist operator lifeline. The intent of this is not explicit in the CIAIAC report but it would appear to be to ensure that the rescuer can always remain attached by their lifeline when swung out under the hoist.

- Modify the procedure for hooking the hi-line bag so that it is hooked through a separate ring on the hoist hook, not to through the main hook itself.

There was a sixth recommendation that a third TCM be carried in case one rescuer became unconscious in the water. This was however rejected as disproportionate and beyond the scope of the internal investigation as needing agreement of multiple parties

To the Safety Department:

- Dissemination of the internal report (or an extract “deemed appropriate”) to SAR crews, “to avoid interpretations based on hearsay and provide reliable information”.

There were two other recommendations to purpose to regulator AESA and SASEMAR that three TCMs were carried. These were however rejected as disproportionate and beyond the scope of the internal investigation as needing agreement of multiple parties.

To the IT Department:

- An anomaly on how training recency can be displayed in certain circumstances but this recommendation was rejected as unnecessary.

The CIAIAC say that “the actions taken are considered to correct and improve those existing before the event”. They therefore made no recommendations.

Safety Resources

The European Safety Promotion Network Rotorcraft (ESPN-R) has a helicopter safety discussion group on LinkedIn. You may also find these Aerossurance articles of interest:

- SAR AW101 Roll-Over: Entry Into Service Involved “Persistently Elevated and Confusing Operational Risk”

- Military SAR H225M Caracal Double Hoist Fatality Accident

- Fatal Fall From B429 During Helicopter Hoist Training

- Hoist Assembly Errors: SAR Personnel Dropped Into Sea A UH-60M accident in Taiwan during a SAR exercise.

- USAF Helicopter Hoist Training Accident: equipment snagged on obstacle

- Fall From Stretcher During Taiwanese SAR Mission (NASC AS365N2 NA-104)

- Fatal Taiwanese Night SAR Hoist Mission (NASC AS365N3 NA-106)

- Fatal Powerline Human External Cargo Flight

- SAR AW139 Dropped Object: Attachment of New Hook Weight

- Swedish SAR AW139 Damaged in Aborted Take-off Training Exercise

- SAR Helicopter Loss of Control at Night: ATSB Report

- Swedish Special Forces SPIES and Military SMS

- SAR Crew With High Workload Land Wheels Up on Beach

- ‘Procedural Drift’: Lynx CFIT in Afghanistan

- Night Offshore Windfarm HEMS Winch Training CFIT (BK117C1 D-HDRJ)

- NH90 Caribbean Loss of Control – Inflight, Water Impact and Survivability Issues

- European Search and Rescue (SAR) Competition Bonanza

- UPDATE 19 February 2022: SAR Hoist Cable Snag and Facture, Followed By Release of an Unserviceable Aircraft

- UPDATE 26 November 2022: Guarding Against a Hoist Cable Cut

- UPDATE 14 May 2023: HH-60L Hoist Cable Damage Highlights Need for Cable Guards

- UPDATE 8 July 2023: BK117 Offshore Medevac CFIT & Survivability Issues

- UPDATE 16 July 2023: SAR AW139 LOC-I During Positioning Flight

Recent Comments