CSB: 12 Years of Deficiencies Prior to Fatal Plant Explosion

The US Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board (the CSB) has released its final report into an explosion and fire at the Williams Olefins ethylene and propylene plant in Geismar, Louisiana (20 miles SE of Baton Rouge), on 13 June 2013, which killed two employees.

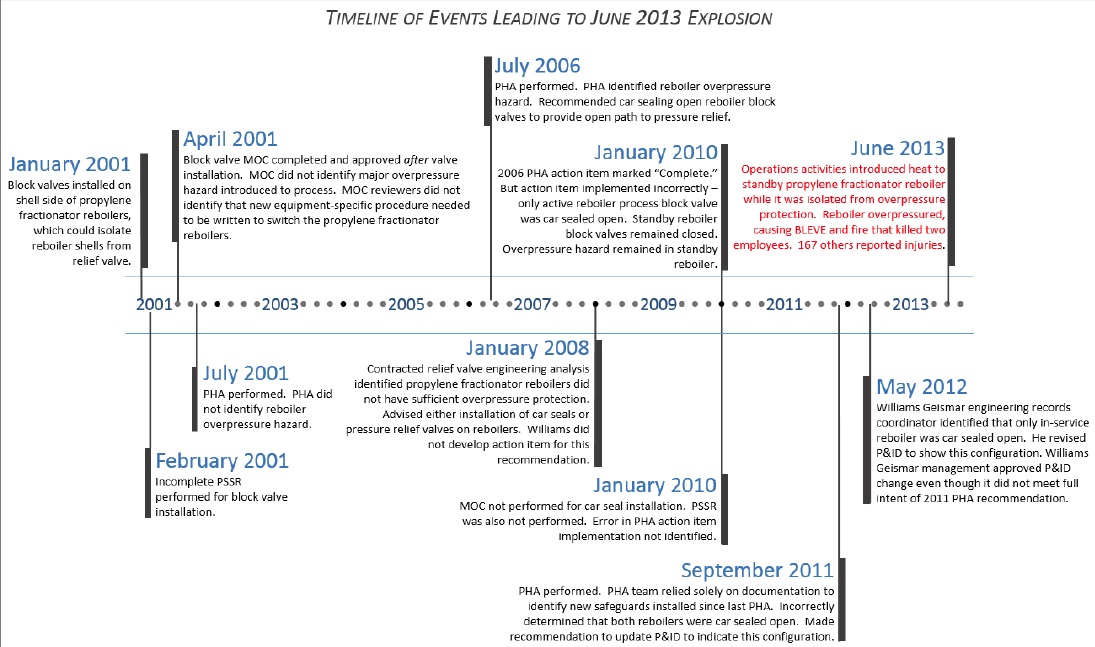

The CSB concluded that process safety management deficiencies during the 12 years prior “allowed a type of heat exchanger called a ‘reboiler’ to…overpressure, and ultimately rupture, causing the explosion”.

The Accident

The unit that failed was approximately 18.5 feet long and over 5 feet in diameter and was one of a pair that were designed in 1967 to be operated together. In 2001, Williams had made modification to enable one reboiler to be isolated at a time, allowing continuous operation with one unserviceable.

The CSB say:

The incident occurred during non-routine operational activities that introduced heat to the reboiler, which was offline and isolated from its pressure relief device. The heat increased the temperature of a liquid propane mixture confined within the reboiler, resulting in a dramatic pressure rise within the vessel.

The reboiler shell catastrophically ruptured, causing a boiling liquid expanding vapor explosion (BLEVE) and fire, which killed two workers; 167 others reported injuries, the majority of which were contractors.

The facility normally employed 110 people but at the time of the incident, around 800 contractors were working on a plant expansion.

Safety Analysis

The CSB say there were failures to:

- Appropriately manage or effectively review two significant changes that introduced new hazards involving the reboiler that ruptured:

- (1) the installation of block valves that could isolate the reboiler from its protective pressure relief device and

- (2) the administrative controls Williams relied on to control the position (open or closed) of these block valves.

- Effectively complete a key hazard analysis recommendation intended to protect the reboiler that ultimately ruptured.

- Perform a hazard analysis and develop a procedure for the operations activities conducted on the day of the incident that could have addressed overpressure protection.

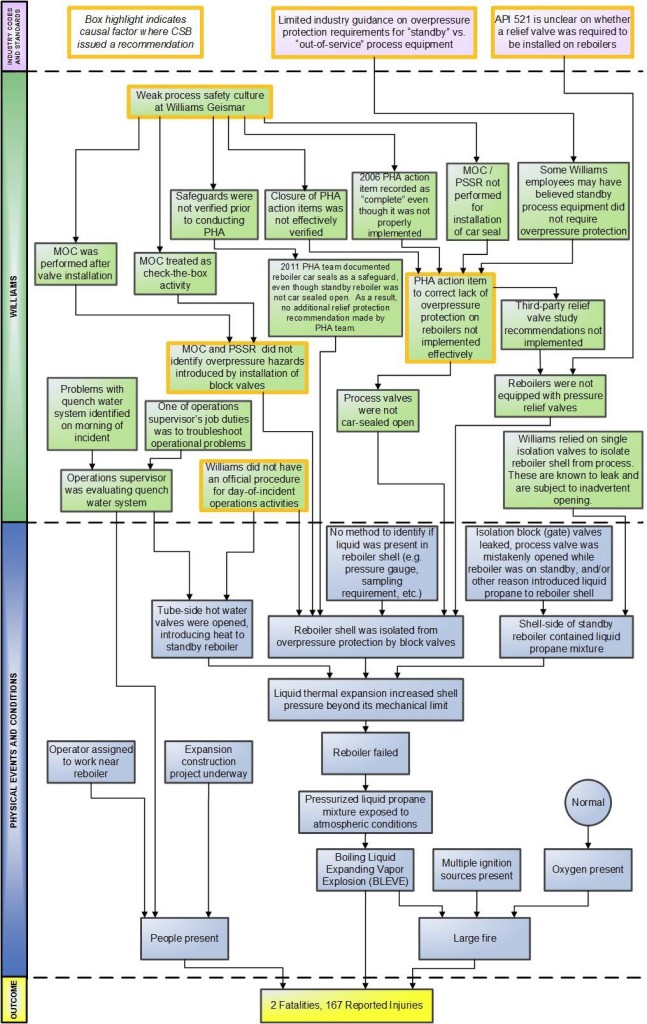

The CSB produced this ‘accimap‘:

These failures developed over a 12 year incubation phase (consistent with the concepts of Barry Turner in his seminar 1978 work Man- Made Disasters):

The CSB say their case study on the incident highlights the importance of:

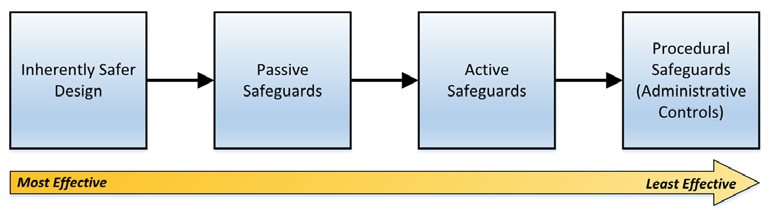

- Using a risk-reduction strategy known as the “hierarchy of controls” to effectively evaluate and select safeguards to control process hazards.

- This strategy could have resulted in Williams choosing to install a pressure relief valve on the reboiler that ultimately ruptured instead of relying on a locked open block valve to provide an open path to pressure relief, which is less reliable due to the possibility of human implementation errors;

- Establishing [what the CSB call] a strong organizational process safety culture.

- A weak process safety culture contributed to the performance and approval of a delayed Management of Change (MOC) that did not identify a major overpressure hazard and an incomplete Pre-Startup Safety Review (PSSR);

- Developing robust process safety management programs, which could have helped to ensure Process Hazard Analysis (PHA) action items were implemented effectively; and

- Ensuring continual vigilance in implementing process safety management programs to prevent major process safety incidents.

Safety Actions and Safety Recommendations

Williams has since implemented improvements which include redesigning the reboilers to prevent isolation from their pressure relief valves.

Before the incident, the Williams Geismar MOC reviews occurred in a sequential process, one person at a time, where the MOC document passed from reviewer to reviewer—a process that often occurred while the reviewers remained in their offices. Following the incident, Williams changed its MOC review to a more collaborative process, requiring an “MOC Review Team” to review every MOC in a group setting.

They also updating their PHA procedure, clarified their use of the terms for “standby” and “out-of-service” equipment and “improved information provided to operators during an event that may require troubleshooting, such as when a process alarm activates”.

CSB recommended that Williams also:

2013-3-I-LA-1 Implement a continual improvement program to improve the process safety culture at the Williams Geismar Olefins Plant. Ensure oversight of this program by a committee of Williams personnel (“committee”) that, at a minimum, includes safety and health representative(s), Williams management representative(s), and operations and maintenance workforce representative(s). Ensure the continual improvement program contains the following elements:

a. Process Safety Culture Assessments. Engage a process safety culture subject-matter expert, who is selected by the committee and is independent of the Geismar site, to administer a periodic process safety culture assessment that includes surveys of personnel, interviews with personnel, and document analysis. Consider the process safety culture audit guidance provided in Chapter 4 of the CCPS book Guidelines for Auditing Process Safety Management Systems as a starting point. Communicate the results of the Process Safety Culture Assessment in a report; and

b. Workforce Involvement. Engage the committee to:

(1) review and comment on the expert

report developed from the Process Safety Culture Assessments, and

(2) oversee the development and effective implementation of action items to address process safety culture issues identified in the Process Safety Culture Assessment report.

As a component of the process safety culture continual improvement program, include a focus on the facility’s ability to comply with its internal process safety management program requirements. Make the periodic process safety culture report available to the plant workforce. Conduct the process safety culture assessments at least once every five years.

2013-3-I-LA-2 Develop and implement a permanent process safety metrics program that tracks leading and lagging process safety indicators…Design this metrics program to measure the effectiveness of the Williams Geismar Olefins Facility’s process safety management programs. Include the following components in this program:

a. Measure the effectiveness of the Williams Geismar Management of Change (MOC)

program, including evaluating whether MOCs were performed for all applicable changes,

the quality of MOC review, and the completeness of the MOC review;

b. Measure the effectiveness of the Williams Geismar Pre-Startup Safety Review (PSSR)

program, including the quality of the PSSR review and the completeness of the PSSR

review;

c. Measure the effectiveness of the Williams Geismar methods to effectively and timely

complete action items developed as a result of Process Hazard Analyses (PHAs),

Management of Change (MOC), incident investigations, audits, and safety culture

assessments; and

d. Measure the effectiveness of the Williams Geismar development and implementation of

operating procedures.Develop a system to drive continual process safety performance improvements based upon the data identified and analysis developed as a result of implementing the permanent process safety metrics program.

2013-3-I-LA-3 Develop and implement a program that demands robust and comprehensive assessments of the process safety programs at the Williams Geismar facility, at a minimum including Management of Change, Pre-Startup Safety Review, Process Hazard Analyses, and Operating Procedures. Ensure that the assessments thoroughly evaluate the effectiveness of these important safety programs. To drive continual improvement of process safety programs to meet good practice guidance, ensure these assessments result in the development and implementation of robust action items that address identified weaknesses. Engage an expert independent of the Geismar site to lead these assessments at least once every three years.

The CSB also identified gaps in American Petroleum Institute (API) standards and issued recommendations to API to strengthen its “Pressure-relieving and Depressuring Systems” requirements to help prevent future similar incidents industry-wide.

Our Observations on ‘Culture’

The CSB’s use of the term ‘safety culture’ shows the difference in the use of such terms between different industries. They say:

An organization’s safety culture is determined by the quality of its written safety management programs (e.g., process safety management procedures, including PHA, MOC, PSSR, operating procedures; written corporate policies) and the quality of implementing those programs by individuals in the organization, ranging from the CEO to the field operator.

We would see this as their Safety Management System. The CSB acknowledge that when they say:

The deficiencies listed above highlight that both a strong written safety management system and effective implementation of that system are required to have good process safety performance.

We think only limited cultural conclusions can be drawn from the circumstances of this single accident, as presented in this report, without devaluing the concept of culture. UPDATE 25 February 2017: See Organizational Culture as Lazy Sensemaking

We do however think that leadership and organisational culture play a part in how organisations develop their SMS and achieve operational excellence, as the CSB go on to note.

CSB’s Broader Lessons

The CSB say:

Lessons to consider include:

(1) Ensure company standards always meet or exceed regulations, industry codes and standards, and best practices;

(2) Verify the facility complies with company standards and procedures through activities such as performing audits and tracking indicators; and

(3) Assess and strengthen the organizational safety culture including the organization’s commitment to process safety.

Item (3) above can be the most challenging to measure and to identify action items to improve performance.

Areas to consider include:

(1) Leaders create culture by what they pay attention to. Is management, from the top down, engaged in process safety? Do leaders require proof of safety rather than proof of danger?

(2) Does the organization have a reporting culture? Is reporting of incidents, near misses, and unsafe conditions encouraged? Can personnel report such occurrences without fear of retaliation? Does the company / site proactively investigate worker safety concerns and implement timely and effective corrective actions?

(3) Does the organization encourage a learning culture? Does it examine incidents outside of the organization? Does it apply relevant lessons broadly across the organization?

(4) Are employees effectively involved in process safety decisions? Before making decisions, is there an open and collaborative process to evaluate problem areas?

5) Are members of the organization overconfident, or do they maintain a healthy sense of vulnerability regarding safety? Are employees susceptible to normalization of deviance?

UPDATE 25 January 2017: The CSB issue a video on the accident: ‘Blocked In’:

The 12-minute safety video includes a 3D animation of the explosion and fire as well as interviews with CSB investigator Lauren Grim and Chairperson Vanessa Allen Sutherland. Grim says:

When evaluating overpressure protection requirements for heat exchangers, engineers must think about how to manage potential scenarios, including unintentional hazards. In this case, simply having a pressure relief valve available could have prevented the explosion.

Other Resources

Aerossurance has previously written about process safety:

- CSB: ‘Multiple Safety Deficiencies’ Led to ExxonMobil Refinery Explosion

- DuPont Reputational Explosion

- Shell Moerdijk Explosion: “Failure to Learn”

- Shell Pernis 11.2t Ethylene Oxide Leak

- Chernobyl: 30 Years On – Lessons in Safety Culture

We have also commented on safety culture and SMS ‘shelfware’ here:

- Culture + Non Compliance + Mechanical Failures = DC3 Accident

- Metro-North: Organisational Accidents

- 10 Year Anniversary: Loss of RAF Nimrod MR2 XV230

- Performance Based Regulation and Detecting the Pathogens

- How To Develop Your Organisation’s Safety Culture

- How To Destroy Your Organisation’s Safety Culture

- The Power of Safety Leadership: Paul O’Neill, Safety and Alcoa

Aerossurance has extensive safety management, organisational culture and safety analysis experience. For safety advice you can trust, contact us at: enquiries@aerossurance.com

Follow us on LinkedIn and on Twitter @Aerossurance for our latest updates.

Recent Comments