Premature A319 Evacuation With Engines Running

On 3 August 2018 CSA Czech Airlines Airbus A319-112 OK-PET was about to depart Helsinki-Vantaa Airport with 135 passengers and 5 crew on board. The Finnish Safety Investigation Authority (SIAF, the Onnettomuustutkintakeskus) describe in their investigation report that:

As the aircraft was taxiing towards the runway, passengers and cabin attendants detected smoke inside the cabin. The purser reported this to the captain by interphone, who then stopped the aircraft on the taxiway.

The situation surprised [the flight crew] because there was no smoke on the flight deck, nor had the aircraft’s systems generated any notifications.

The Captain believed the smoke originated from the cargo compartment.

CSA Airbus A319 OK-PET Stopped at Helsinki Airport on 3 August 2018 after Smoke was Reported in the Cabin (Credit: SIAF)

A moment later the purser asked the captain for permission to evacuate the aircraft.

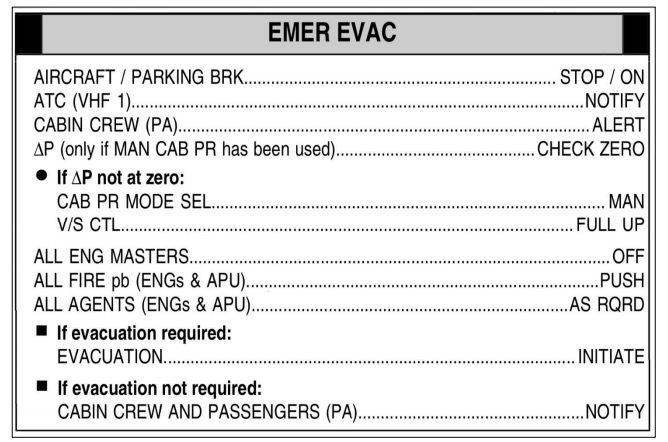

…the captain tried to act quickly and failed to complete the procedures in the order of the evacuation checklist.

For example:

…the captain activated the evacuation signal even though the engines were still running. The cabin crew initiated the evacuation.

Furthermore:

The captain did not make an evacuation announcement and, therefore, not everyone recognised what the evacuation signal meant. Some passengers thought that it was a normal deplaning. During the evacuation some passengers rushed past slower-moving passengers and children were trampled over. Also, the carry-on luggage that some passengers took along slowed down the evacuation.

The evacuation was done using emergency slides at four cabin doors. In the beginning of the evacuation the engines were still running, which put the first passengers who deplaned through the front doors in danger of being ingested into a running engine. It was not possible to use the emergency slides at the rear doors while the engines were still running.

During the evacuation 26 passengers sustained minor injuries. Their injuries were mild, caused by the congestion in the aisle and from using the emergency slides.

Since the passengers were not gathered together, most of them remained in the vicinity of the aircraft. Some of them ran onto the grassy area between the aircraft and RWY 15/33. At this stage, when no-one was controlling them, they could have entered the active runway. The shift supervisor of airport rescue service, upon arrival [after c 8 minutes], took control of the passengers and told them to gather at a safe area.

Air navigation service provider ANS Finland stated that “while, in theory, it was possible for the passengers to enter runway 15, it was highly unlikely because of the difficult terrain and the physical distance”.

Safety Investigation

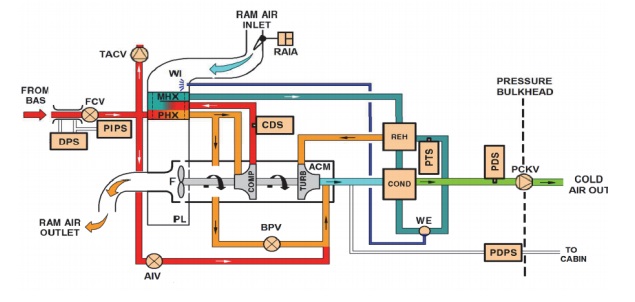

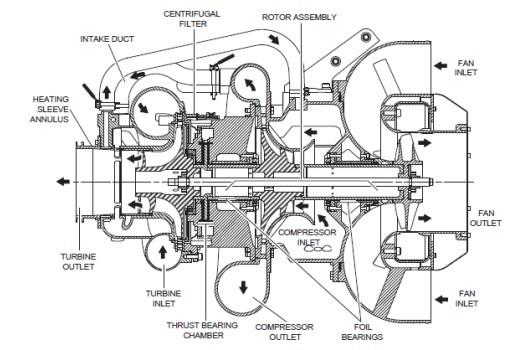

Investigators found the origin of the smoke was a seized Air Cycle Machine (ACM) bearing. The ACM is part of the aircraft’s air conditioning system.

When the unit failed, it generated smoke which was ducted through the air conditioning system into the cabin.

The running time on the piece of equipment was 28067 hours, including 14047 starts.

The ACM bearing and the subsequent generation of smoke has occurred before in the A320 family fleet. For example: UK AAIB investigation into a smoke event to EasyJet A319-111, G-EZIM at Isle of Man Airport, 31 March 2017.

Safety Analysis and Conclusions

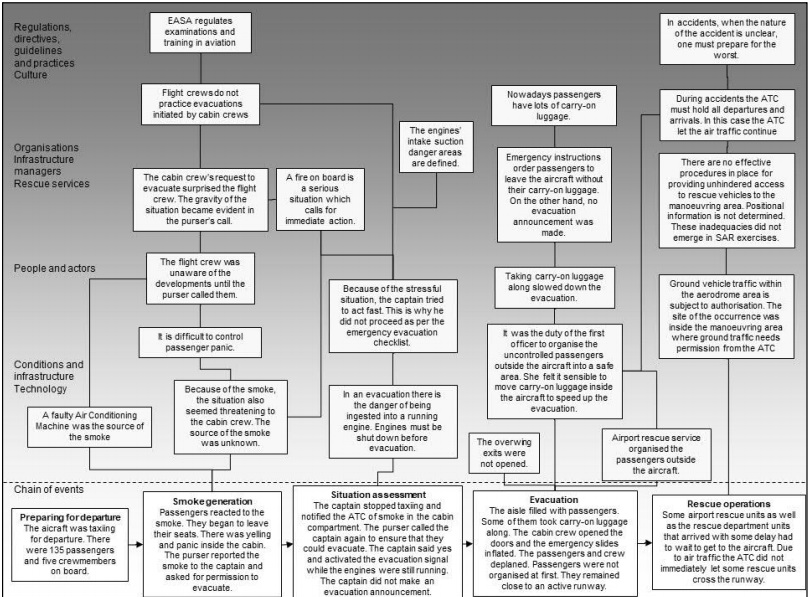

SIAF developed an AcciMap that summarises their analysis:

The SIAF conclusions were:

- In training the captain issues the command to evacuate and, therefore, evacuation initiated by the cabin crew had not been practiced. Conclusion: Evacuations initiated by the cabin crew are not normally practiced in commercial air transport.

- Because of the stressful situation, the captain tried to act quickly and, therefore, did not complete the evacuation checklist procedures in the correct order. Passengers were in danger of being ingested into the running engine. Conclusion: The Emergency Evacuation Checklist is not well-suited for situations in which the cabin crew initiate evacuation.

- The passengers that evacuated from the airplane were left unsupervised for nearly eight minutes on the manoeuvring area. They could have entered the active runway which was in use for arriving traffic. Conclusion: In an accident the air traffic control must prevent additional damage from occurring and also suspend, when required, arriving traffic.

- All of the rescue units and police patrols were not allowed to the accident site without delay. Conclusion: Helsinki-Vantaa Airport does not have effective procedures in place for providing unhindered access to rescue units, ambulances and police patrols to accident sites on the manoeuvring area

A Similar Case of an Evacuation Commencing with the Engines Running

The US National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) investigated an occurrence SIAF say was similar. On 8 September 2015, British Airways Boeing 777-236ER G-VIIO suffered an uncontained GE GE90 engine failures and fire during the take-off run.

SIAF comment

Take-off was aborted and the flight crew completed the procedures for an engine fire. The fire, however, was uncontrollable, and the captain had to rapidly make the decision to evacuate the aircraft.

The flight crew activated the evacuation signal and the cabin crew initiated the evacuation. They did not comply with the evacuation checklist and, as a result, the right engine was inadvertently left running. The fire, and the fact that the right engine was running, slowed down the evacuation and only two of the eight emergency exits could be used for evacuation.

There are some similarities between that accident and the occurrence now being investigated. The captain was very experienced. It is possible that, during the situation, he felt the need to evacuate the aircraft so urgently that he did not have the time to complete the checklist.

SIAF Safety Recommendations

- The European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) ensure that operators, in their procedures and training, take into account the situation where evacuation is initiated without waiting for the captain’s command.

- The EASA ensure that Airbus, in their emergency evacuation procedures, re-evaluate the situation where it becomes necessary to immediately shut down the engines.

- The Finnish Transport and Communications Agency ensure that Helsinki-Vantaa Airport develops effective procedures that guarantee unhindered access for authorities in charge of, and participating in, rescue operations to an accident site on the manoeuvring area.

EASA note that “regulations require operators to ensure that their procedures and training take into account situations in which the cabin crew initiates an evacuation without the captain’s command.” Airbus noted that the crew would have “enough time to complete the evacuation checklist and shut down the engines before the passengers deplaned”.

Safety Resources

Past Aerossurance articles:

- Delta MD-88 Accident at La Guardia 5 March 2015 The use of excessive reserve thrust resulted in loss of direction control but noticeably there was a significant delay to the evacuation (which took 17 minutes to complete).

- Easyjet A320 Flap / Landing Gear Mis-selections

- HF of the Selection of Parking Brake Instead of Speed Brake During a Hectic Approach

- AAIB: Human Factors and the Identification of Saab 2000 Flight Control Malfunctions

- Procedural Drift at Saab 340 Operator Leads to Taxiway Excursion

- Improvised Troubleshooting After Cascading A330 Avionics Problems

- British Midland Boeing 737-400 G-OBME Fatal Accident, Kegworth 8 January 1989

- Challenge Assumptions: ATSB on A330 with a u/s GPS

- Gulfstream G-IV Take Off Accident & Human Factors

- Confusion of Compelling, But Erroneous, PC-12 Synthetic Vision Display

- ATR 72 In-Flight Pitch Disconnect and Structural Failure

- C-130J Control Restriction Accident, Jalalabad

- B777 in Autoland Mode Left Runway When Another Aircraft Interfered With the Localiser Signal

- Distracted B1900C Wheels Up Landing in the Bahamas

- HF Lessons from an AS365N3+ Gear Up Landing

- B737 Speed Decay, Automation and Distraction

- Wrong Engine Shutdown Crash: But You Won’t Guess Which!: BUA BAC One-Eleven G-ASJJ 14 January 1969

- UPDATE 10 June 2020: B767 Fire and Uncommanded Evacuation After Lockwire Omitted

And in particular:

Also see our review of The Field Guide to Understanding Human Error by Sidney Dekker presented to the Royal Aeronautical Society (RAeS): The Field Guide to Understanding Human Error – A Review

Also see the RAeS Specialist Paper: Emergency Evacuation of Commercial Passenger Plane UPDATE 7 July 2020: Updated RAeS Passenger Evacuation Paper now available

UPDATE 6 August 2020: The UK AAIB have reported on another case of a premature evacuation: AAIB investigation to Airbus A320-214, OE-LOA Evacuation following rejected takeoff due to left engine failure, London Stansted Airport, 1 March 2019.

UPDATE 2 September 2020: Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) releases its investigation into the 10 May 2019 collision between a fuel truck and Jazz DHC-8-300 C-FJXZ at Toronto/Lester B. Pearson International Airport, Ontario.

Following the collision, because the fuel tanker was not visible from the flight deck or from the flight attendant’s position in the cabin, both the flight crew and the flight attendant needed a few moments to assess what had occurred and decide on the best course of action regarding a rapid deplanement or evacuation. In addition, the flight crew required some time to shut down the engines and allow for the propellers to stop turning before passengers could safely exit the aircraft.

After the flight crew shut down the engines, the captain called the flight attendant via the interphone and instructed her to initiate a rapid deplanement. The flight attendant answered the call, but had difficulty hearing the captain over the noise of the passengers. At that time, the smell of fuel and/or engine exhaust reached the cockpit, and the captain gave the order over the passenger address system to evacuate.

However, nobody on the aircraft reported hearing the captain’s evacuation order, possibly due to the passenger address system being damaged by the impact, and/or passenger noise in the cabin. Due in part to increasing pressure from the passengers, including verbal threats from one of them, the flight attendant opened the main door (exit L1) slowly. When the flight attendant smelled fuel, she decided to initiate an emergency evacuation.

The hazards that existed were all closer to the rear of the aircraft, which made the use of the front exits an appropriate choice; however, the decision to block the right-hand front emergency exit door (exit R1) because of the risk of injury to passengers increased the evacuation time.

Some passengers seated along the left side of the aircraft had seen the oncoming fuel tanker and were aware that a collision was imminent. Approximately 30 seconds after impact, while the propellers were still turning, some passengers near the rear of the aircraft decided to act on their own by opening the rear emergency window exits without waiting for directions from the flight crew or flight attendant.

When the rear emergency window exits were opened, the smell of exhaust and noise of the engines entered the cabin and may have been interpreted by the passengers as a significant risk of fire and/or explosion, which resulted in an increase in panic.

UPDATE 7 January 2021: Airbus publishes Attention Crew at Stations with advice on evacuation best practice.

Recent Comments