Fatal MD600 Collision With Powerline During Construction (High Line Helicopters N602BP)

On 8 April 2018 MD Helicopters MD600N N602BP, operated by High Line Helicopters as a Part 133 external load flight, was destroyed when it collided with power line support structure in Smethport, Pennsylvania during a utility construction project.

The pilot was seriously injured and two linesmen were fatally injured. According to the US National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) investigation report issued in December 2019:

High Line Helicopters was hired as an independent contractor by J.W. Didado Electric, LLC, a subsidiary of Quanta Services, Inc., to transport J.W. Didado employees to job sites for new power line construction. First Energy Corporation hired J.W. Didado to perform the construction.

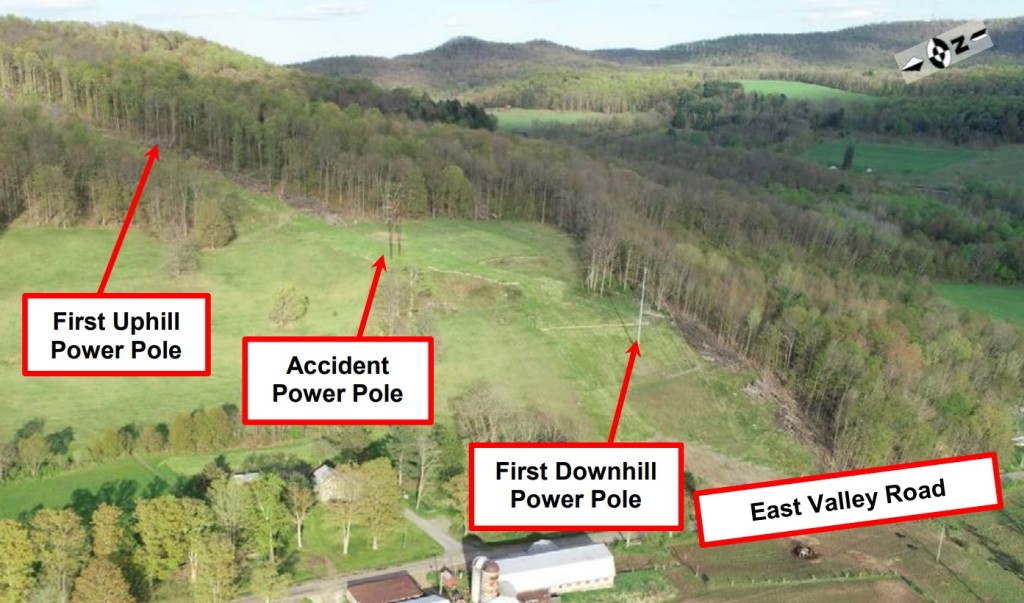

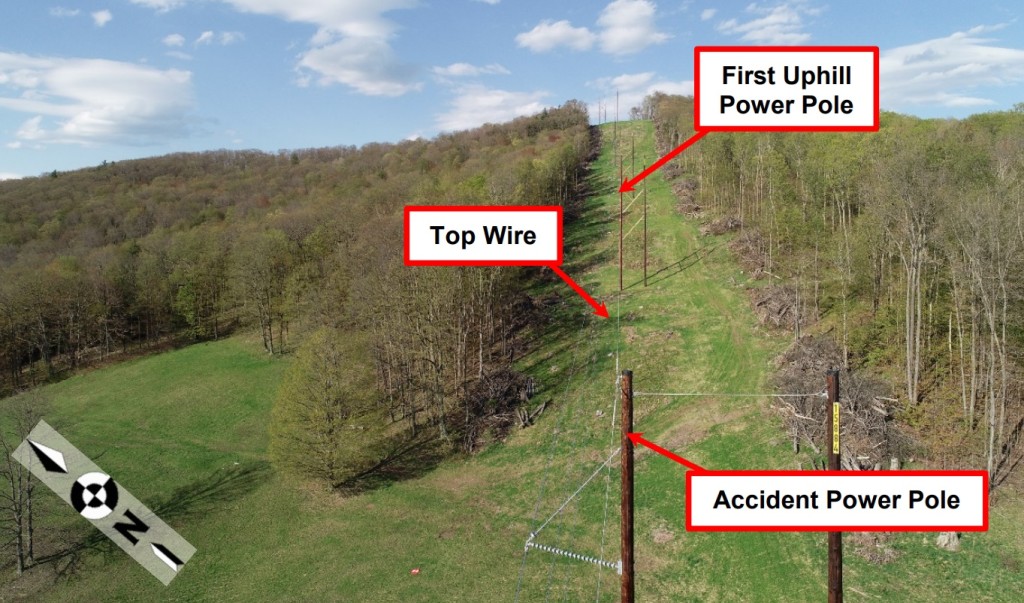

Three power lines, which were newly constructed in mountainous terrain and oriented approximately east/west, were supported by structures that were constructed of either wood (dual pole, H-frame) or steel (single pole). A static line was affixed to the top of the structures above the power lines.

The purpose of the flight was to remove the static line from the wheeled pulley device (dolly) that temporarily secured the static line and permanently secure the static line to the structures (“clipping wire”).

One lineman completed the task from the skid of the hovering helicopter, and another lineman inside the helicopter passed tools and equipment back and forth to the lineman on the skid.

The pilot then repositioned the helicopter so that the linemen could repeat the steps on the next structure. During a postaccident interview, the pilot reported that he and the linemen (the crew) met earlier in the day and flew to one of the structures to assess the work and tools required to complete the task. The helicopter then returned to the landing zone and was refueled before departing on the accident flight. The crew completed one structure, and the pilot hovered the helicopter into position so that work could begin on the next structure.

…the pilot stated that the pole where the accident occurred was at “a slight inside angle” but was considered to be a “safe” area in which to work. According to the pilot and the operator, the helicopter was hovering “inside the bite,” which was the triangular area comprising the wire from the uphill pole, the turn at the accident pole, and the wire to the downhill pole. The “base” of the triangle was the horizontal line from the uphill pole to the downhill pole. The operator indicated that the “bite” had a vertical dimension as well. When asked to describe operations “inside the bite,” the [operator’s] safety director stated that it was the area where, once the helicopter was inside it, the wire would move toward the helicopter if the wire became loose from the dolly.

Once the helicopter was in position, the lineman on the helicopter skid attached the first half of the armor rod ahead of the dolly and manipulated the line and the dolly to complete the wrap.

The pilot and the linemen began work without installing a safety strap. According to the operator’s director of safety, the safety strap aboard the helicopter was “not long enough” to install it before work began…and that a “choker safety” should have been used. When asked if the company’s standard operating procedures directed that the crew retrieve the choker safety, the director of safety replied, “that is more or less a contractor thing” and that High Line Helicopters did not have procedures for contractor equipment. [However,] Quanta Services [indicated] that the…training of linemen for helicopter operations was the responsibility of the helicopter contractor.

According to the pilot, the lineman opened the spring-loaded locking gate on the dolly above the static line to wrap the second half of the armor rod, which was “normal” before the attachment of the safety. About that time, the pilot felt the helicopter being “pulled” toward the structure. The pilot stated that he made full right cyclic and full left pedal inputs to avoid colliding with the structure but that “all I remember is rolling over the structure.” The pilot said that he neither felt nor heard anything unusual before the helicopter was “pulled” toward the structure.

A witness to the accident stated that, while the helicopter was hovering, its nose turned away from the pole, and the helicopter “was violently forced back to the pole.” The witness also stated that the tail section struck the pole and that the helicopter “broke in two,” after which the helicopter appeared “to fall straight down.”

The witness did not see the helicopter’s impact but stated that the engine “continued to surge.”

The helicopter descended vertically between and adjacent to the dual-pole structure. The tailboom and the six rotor blades from the main rotor separated from the helicopter during the descent.

Wreckage of High Line Helicopters MD Helicopters MD600N N602BP Recovered for Inspection (Credit: via NTSB)

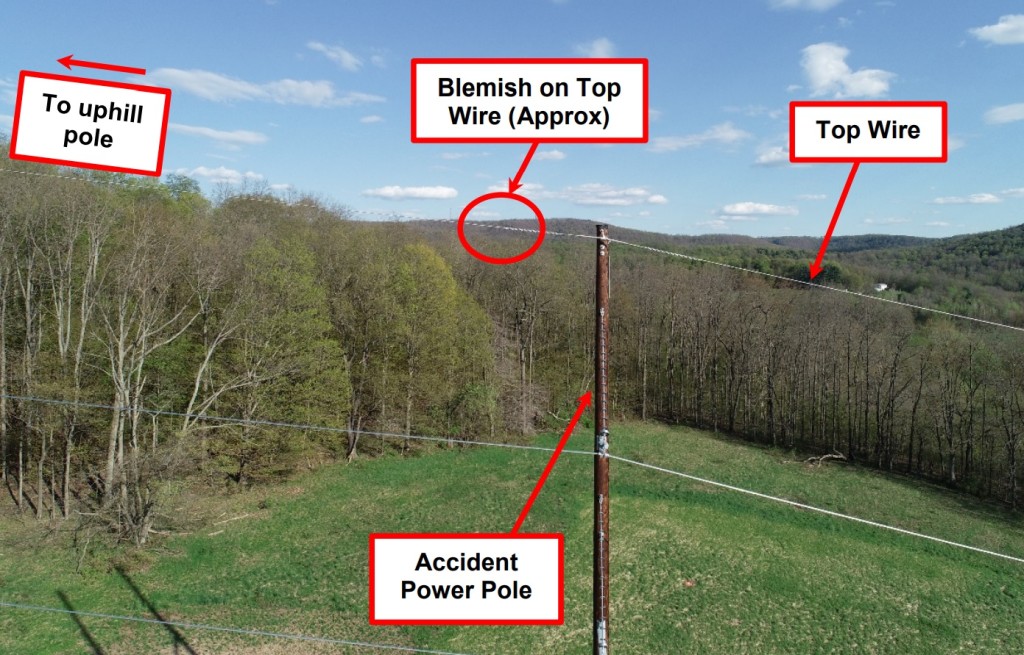

Examination of the structure poles and the static line revealed signatures consistent with blade strikes.

Damage to Blue Main Rotor Blade (MRB) of High Line Helicopters MD Helicopters MD600N N602BP (Credit: via NTSB)

Blemishes on the static line, about 11 feet uphill (east) of the structure where the dolly was mounted, displayed smearing signatures consistent with a high-speed, metal-to-metal strike.

The dolly locking gate had failed in overload.

The pilot had…

…accrued about 6,200 hours of total flight experience, 250 hours of which were in the 600N helicopter. The operator estimated that that pilot had accrued 3,000 hours performing power line operations.

In relation to airworthiness:

An FAA airworthiness inspector reviewed the helicopter’s maintenance records. The inspector found numerous record-keeping errors but overall compliance with hourly and calendar inspections as well as compliance with airworthiness directives.

The helicopter was installed with aluminum diamond-plate flooring, which required the removal of the left-side cabin door, and a 6061-T6 aluminum pipe. [N]o records were found showing FAA approval for these modifications or company documentation of weight and balance computations that reflected the changes.

According to section 2-1 of the MD 600N flight manual, operations with the left-side cabin door removed were authorized, but operations with the pilot (right) seat removed (resulting in a left-seat command configuration) were not. Neither of these modifications was reflected in the helicopter’s weight and balance or aircraft records.

Title 14 CFR 91.107(a)(3) required that all passengers be seated in an approved seat and properly secured with a seatbelt during aircraft movement. The helicopter’s cabin had no passenger seats installed.

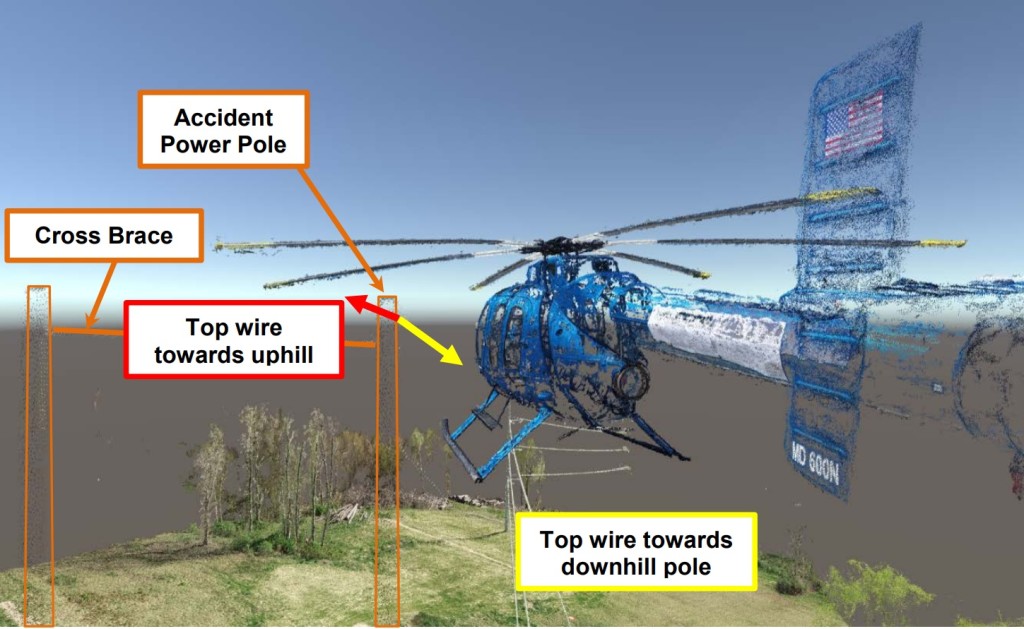

The NTSB deployed DJI Phantom 4 Professional V2 and DJI Phantom 4 Advanced unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) drones to conduct aerial imaging at the accident site. A three-dimensional point cloud/surface model of the MD600 helicopter was also created to visualise the location of the helicopter relative to the wires and poles.

Visualisation of MD600 N602BO Adjacent to the Wires. Note: the Blades were Modelled Static / Unloaded (Credit: NTSB)

Previous Related High Line Helicopters Accidents

A review of the NTSB’s accident database revealed that the operator was involved in three accidents within a 3-month period in 2018, including this accident.

The first accident (ERA18LA091) occurred in San Juan, Puerto Rico on January 11, 2018, and the second accident (CEN18LA121) occurred in Blair, Wisconsin, on March 7, 2018, and involved the accident pilot. The accident in Smethport, Pennsylvania, occurred about 1 month later.

For the first accident (ERA18LA091), the NTSB found that probable cause was the helicopter pilot’s improper decision to use an open-end grapple, instead of an A-frame attachment, to lift and move a ladder with a lineman on it and the lineman’s improper decision to be lifted on a ladder via an open-end grapple, which were contrary to company policy and the Federal Aviation Regulations.

N571HH H369 Moved a Ladder by Grappling Hook: It Fell and Caused a Serious Injury to a Linesman on the Ground (Credit: NTSB)

For the second accident (CEN18LA121) the NTSB determined that the probable cause was the pilot’s failure to recognize and compensate for hazards during the human cargo external load operation, which led to a collision between a lineman, who was the external load, and a live power line [resulting in a serious injury]. FAA inspectors determined the company’s Rotorcraft External Load Flight Manual had inadequate procedures and training for human external cargo.

Safety Actions at High Line Helicopters

During the investigation, FAA aviation safety inspectors identified areas within the flight and maintenance departments for improvement. Inspectors visited the operator’s facilities, presented a “maintenance demonstration,” and provided templates for documents and standard operating procedures for recordkeeping and pilot training. During a subsequent aircraft conformity inspection, an FAA aviation safety inspector (airworthiness) noted that the operator had incorporated the documents provided and that no deficiencies were noted.

As a result of this accident investigation, the president of High Line Helicopters mandated the installation of safety straps to wires before work begins. The safety straps are to remain in place until work is completed at each structure.

NTSB Probable Cause

The helicopter pilot’s failure to maintain adequate clearance during power line construction work, which resulted in the helicopter’s main rotor striking and becoming entangled with a wire and a subsequent dynamic rollover and collision with terrain.

Contributing to the accident was the pilot’s and linemen’s decision to continue work without a secondary safety device installed, which was contrary to standard operating procedures.

Safety Resources

- The Tender Trap – the design of aviation service tenders and contracts

- Fatal Powerline Human External Cargo Flight

- Beware Last Minute Changes in Plan

- RCMP AS350B3 Left Uncovered During Snowfall Fatally Loses Power on Take Off

- Loose Engine B-Nut Triggers Fatal Forced Landing

- Fatal Engine Power Loss: Powerline Helicopter Not Modified IAW OEM Recommendations

- Fatal H500 / 369D Low Altitude Hover Power Loss: Power Line Maintenance Project

- Tool Bag Takes Out Tail Rotor: Fatal AS350B2 Accident, Tweed, ON

- Unexpected Load: AS350B3 USL / External Cargo Accident in Norway

- Helicopter Wirestrike During Powerline Inspection

- Fatal Snowy Powerline Inspection Flight

- UPDATE 2 May 2020: Sécurité Civile EC145 SAR Wirestrike

- UPDATE 26 July 2020: Impromptu Landing – Unseen Cable

- UPDATE 20 September 2020: Hanging on the Telephone… HEMS Wirestrike

- UPDATE 23 January 2021: US Air Ambulance Near Miss with Zip Wire and High ROD Impact at High Density Altitude

- UPDATE 5 March 2021: Wire Strike on Unfamiliar Approach Direction to a Familiar Site

- UPDATE 3 September 2022: Garbage Pilot Becomes Electric Hooker

Recent Comments