Maintenance Personnel Fatigue and Alertness

Maintenance personnel fatigue and a consequential lack of alertness is regularly being identified as contributory, or potentially contributory, to maintenance related air accidents and serious incidents. We have covered three examples previously:

Some involve poor shift patterns: Missing Igniters: Fatigue & Management of Change Shortcomings: The UAE GCAA investigation report explains most of the maintenance personnel were working a 56 days on / 28 days off shift pattern with no intermediate rest days.

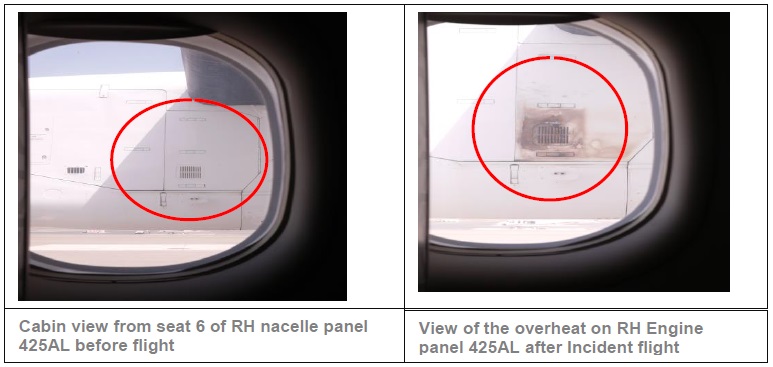

Some involve shortages of personnel and overtime: e.g. A319 Double Cowling Loss and Fire: The UK AAIB investigation report highlighted that due to long-term staff shortages both the personnel directly involved were working overtime (one had worked 70.2 hours in total in 7 days, the other 55.8 hours).

And involve last minute changes of rosters, sleep patterns and working on until a job is complete: e.g. Fatal $16 Million Maintenance Errors: In this fatal accident the US NTSB the two personnel, were asked to come in early the next day during their rest period. The mechanic managed just 5 hours sleep that night, the inspector 7 hours. The critical inspection was completed near the end of a 13 hour 24 minute shift.

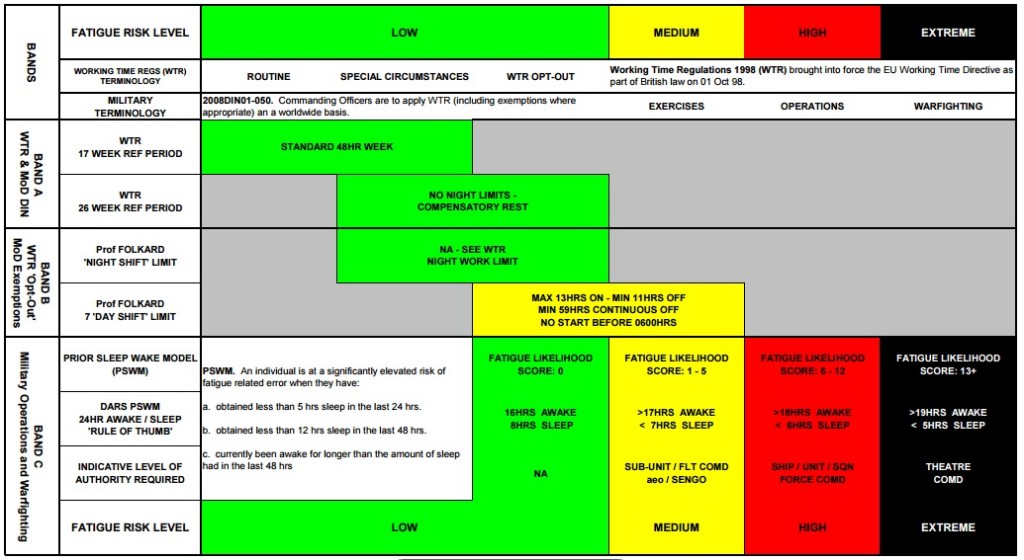

In 2010 the Royal Aeronautical Society (RAeS) Human Factors Group: Engineering (HFG:E) published a Guidance Paper Military Maintainer & Groundcrew Working Hours and Fatigue Risk Management by Major Chris Evans and an associated risk assessment diagram:

This model was designed to be a quick but useful way to predict fatigue in combat deployments. There other techniques such as the HSE fatigue and risk index tool used by the AAIB during the A319 investigation. UK CAA Paper 2002/06 – The Folkard Report is also a useful resource.

If you found this helpful you might like these other Aerossurance articles:

- Maintenance Human Factors: The Next Generation

- Aircraft Maintenance: Going for Gold?

- Professor James Reason’s 12 Principles of Error Management

- Back to the Future: Error Management

- How To Develop Your Organisation’s Safety Culture

- Critical Maintenance Tasks: EASA Part-M & -145 Change

- Does Continuation Training Change Behaviours?

- Coaching and the 70:20:10 Learning Model

- UPDATE 4 April 2016: Fatigued Flight Test Crew Crosswind Accident

- UPDATE 14 June 2017: Perception and Fatigue: CH124 Sea King Engine Failure

This article was originally published on LinkedIn.

UPDATE 10 July 2018: Delighted to have co-presented at a World Food Program (WFP) webinar on alertness and maintenance fatigue today.

Other research, from healthcare, highlights that compliance with routine ‘secondary’ requirements, such as hand washing, drops the longer a shift is, but do improve the longer the intermediate rest period is:

NTSB Most Wanted 2014:

UPDATE 23 March 2016: The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has launched a consultation on AC120-MFRM Maintainer Fatigue Risk Management:

This advisory circular (AC) describes the basic concepts of human fatigue and how it relates to safety for aviation maintenance organizations and individual maintainers; provides information on Fatigue Risk Management (FRM) in terms of fatigue hazards and mitigation strategies specific to aviation maintainers; describes the benefits of implementing FRM methods within aviation maintenance organizations; and identifies methods for integrating FRM within a Safety Management System (SMS) (if applicable).

Personnel fatigue was first identified as a critical issue in aviation maintenance by the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) in 1996, stemming from the ValuJet accident in Florida. Since then, it continued to gain attention as a maintenance safety risk:

1) In 2000, an FAA field study that collected 50,000 hours of ActiGraph data from maintenance personnel across multiple organizations found that maintainers were typically getting about 5 hours of sleep;

2) In 2006, an FAA survey of international human factors (HF) programs in maintenance organizations revealed that over 80 percent of those responding indicated that human fatigue was an issue;

3 In 2008, an FAA conference on human fatigue revealed that scientists, regulators, company management, and labor representatives all agreed that human fatigue poses a safety hazard in the aviation maintenance industry and that individuals, and government and civilian organizations, need to take appropriate action; and

4) In 2010, the FAA Administrator publicly committed to review all aspects of FAA regulations that address human fatigue.

Comments are due 31 May 2016.

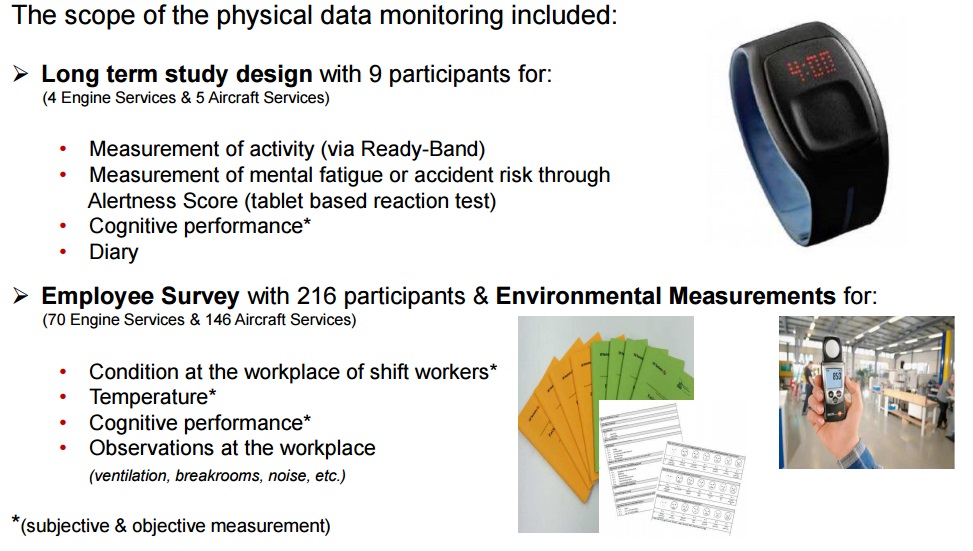

UPDATE 1 August 2016: Antonio Härry of SR Technics presented on Implementation of a Fatigue Risk Management System to Initiate Sustainable Improvements in Maintenance Operations at the Safety Management International Collaboration Group (SM ICG) Industry Day in Rome in June 2016. Its noticeable that their approach included multiple data gathering techniques:

UPDATE 29 September 2016: While note aviation maintenance related, the UK Rail Accident Investigation Branch (RAIB) has published a report on two Signals Passed at Danger (SPADs) that both involved fatigue:

Both incidents occurred because the train drivers involved were too fatigued to properly control their trains; both drivers stated that they momentarily fell asleep on the approach to the signals concerned. They were suffering from fatigue because they had not obtained sufficient sleep, which in part was due to the rest facilities at Acton not being fit for purpose, and because the drivers were nearing the end of a long night shift. Neither driver reported as unfit for duty, which was also causal to the incidents. The investigation identified underlying factors associated with supervision and management at the drivers’ home depot in Westbury, and with the general approach to the management of fatigue within the company.

As a result of this investigation, RAIB has made three recommendations covering shift planning at Westbury depot, fatigue management within the freight sector and identification of fatigue risk through data analysis.

RAIB has also identified two learning points concerning the importance of preparing for duty and reporting fatigue, and the role of napping (and facilities for such) within a fatigue risk management system.

Simon French, Chief Inspector of Rail Accidents said:

Whilst recognising the efforts that are already being made by the freight operating companies to address this difficult issue, this investigation has revealed that there is more that can be done to identify the types of duty that are more likely to cause dangerous levels of fatigue, and the members of staff who are at particular risk.

Although there are mathematical models that can be used to help managers identify high risk turns of duty, the best intelligence is likely to be gained from those who actually do the work.

To be really effective a fatigue management system needs to draw on the experience of drivers and should be informed by a constructive dialogue between staff and managers on the ways that fatigue can best be managed, whilst also meeting the needs of the business.

Such a collaborative approach will deliver the best results if it is based on trust, openness and a recognition that all human beings have the same basic need to be rested if they are to perform at their best. An admission of tiredness should not be seen as a weakness – it may be the unavoidable consequence of the work and home demands placed on a driver.

Good fatigue management requires the employer and the employee to recognise their respective responsibilities. For drivers, there is an obligation to ensure that they are sufficiently rested before taking duty, and for employers, the need to reduce fatigue-induced risk so far as reasonably practicable.

UPDATE 15 March 2017: The IOSH Magazine discusses “The wide-awake club”: Promoting the benefits of alertness may engage employees more than warning of the perils of fatigue. It describes how managing and reacting to fatigue, it’s a very poor strategy, because at that point the options are limited. The article also noted that reliance on fatigue is fraught with difficulty:

…there are more fundamental issues that deter reporting, such as fear that a request for shifts will be turned down, or may send a signal to their employers that they cannot take on extra duties.

We are also aware of cases were when fatigue is reported by personnel who ‘stand themselves down’ from duty, it is ‘reclassified’ as sickness, playing down the cause. Emphasising alertness, allows easier reporting of precursor deteriorations.

When the focus is on alertness reporting, more proactive risk management data is produced.

In some airlines’ pre-flight crew briefings the captain asks each member how alert they feel and how much sleep they have had.

Tools for evaluating self-reported levels of alertness include the seven-point Samn Perelli Scale, which ranges from “fully alert, wide awake” to “completely exhausted”, and the nine-point Karolinska Sleepiness Scale, which starts at “very alert” and goes down to “very sleepy”.

UPDATE 10 June 2017: 8 Myths About Sleep and Fatigue from HunanFactors101.com:

UPDATE 19 June 2017: Ingestible Stomach Acid-Powered Health Monitoring Pill. An MIT sensor with a energy harvesting galvanic cell offers exciting possibilities to fatigue and alertness researchers.

UPDATE 6 July 2017: Another hidden cost of fatigue: Sleep deprivation among trainee doctors and anaesthetists is causing accidents or near misses on way home, report says

In all, 1,229 (57%) of 2,155 trainee anaesthetists questioned had been involved in an accident, or come close to having one, while driving, motorcycling, cycling or walking home after working all night.

“I have fallen asleep at traffic lights. I once hallucinated on the motorway,” one doctor said. Another said: “Previously experienced microsleep/nodding off on the M5. Foot came off the gas pedal and the car slowly drifted into middle lane. Woke up when driver in van came up alongside me and honked continuously.”

UPDATE 30 March 2019: Contaminated Oxygen on ‘Air Force One’ Poor standards at a Boeing maintenance facility, partially fatigue related, resulted in contamination of two oxygen systems on a USAF Presidential VC-25 (B747).

UPDATE 12 July 2019: The AAIB highlight an engineer who changed a landing gear component and omitted to transfer a bushing had worked 31 days with only 2 rest days: AAIB investigation to Airbus Helicopters EC175B, G-EMEA (Nose landing gear collapse due to misassembly of the nose landing gear A-frame during installation, Aberdeen Airport, 10 July 2018).

UPDATE 12 October 2019: ATR72 VH-FVR Missed Damage: Maintenance Lessons Unclear communications, shift handover & roles and responsibilities, complacency about fatigue and failure to use access equipment all feature in this serious incident.

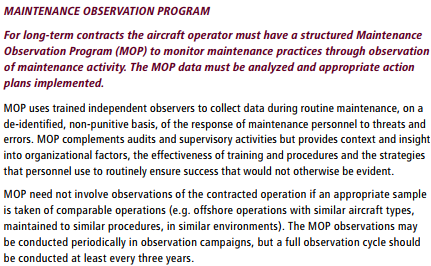

Aerossurance worked with the Flight Safety Foundation (FSF) to create a Maintenance Observation Program (MOP) requirement for their contractible BARSOHO offshore helicopter Safety Performance Requirements to help learning about routine maintenance and then to initiate safety improvements:

Aerossurance can provide practice guidance and specialist support to successfully implement a MOP.

Aerossurance is delighted have sponsored an RAeS HFG:E conference at Cranfield University on 9 May 2017, on the topic of Staying Alert: Managing Fatigue in Maintenance (see Twitter #stayingalert). This event will feature presentations and interactive workshop sessions.

Aerossurance is pleased to be supporting the annual Chartered Institute of Ergonomics & Human Factors’ (CIEHF) Human Factors in Aviation Safety Conference for the third year running. This year the conference takes place 13 to 14 November 2017 at the Hilton London Gatwick Airport, UK with the theme: How do we improve human performance in today’s aviation business?

Aerossurance is pleased to be both sponsoring and presenting at a Royal Aeronautical Society (RAeS) Human Factors Group: Engineering seminar Maintenance Error: Are we learning? to be held on 9 May 2019 at Cranfield University.

Recent Comments